“Who looks far down on the heavens & the earth” | The Byzantine Christ enthroned

In this essay,

• THE ISSUE OF LANGUAGE TROUBLE IN OUR UNDERSTANDING

• & THE HELP OF ART IN CHURCHES

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | Sovereignty

Do a search in the text of the Bible for the word ‘sovereign’ (of course we are just searching a translation) and we find that this word is used three times only. We, however, think in terms of God’s ‘sovereignty’, it is this term that comes to mind when we think about the reality to which this word is attached – that is, the reality comes packaged like this.

On the one hand, this packaging looks to be evidence that (as some theorists have suggested) we think in the language we speak. On the other, however, it might be the sign of a liability: that we think in the short-hand of abstract language, think lazily.

This may be a bad habit: translating experience or reported realities into a word (which is of course not translating at all, but simple link-finding: latching onto the most familiar label) and then circulating in the space that that language affords, however much or little it is.

There are situations in which, standing on the threshold of something real, we are given the ‘educated’ option of turning right away to a term, a concept – to the meaning popularly attached to this word that we fall back on – and we are then hemmed in by that language.

Thinking in language can be a liability. Your lexicon of meaning – the meaning handed to you by your culture in its standard grasp of the term ‘sovereign’ – could cheat you of what you might have had by, perhaps, not being so quick and smart.

PLATO’S ADVICE

Readers of Plato’s cave allegory, by the way, often overlook the fact that the things that cast the shadows seen on the cave wall (the most unreflective people in society can see only these shadows) are described by Plato as “statues” and “figures of animals”: replicas of actual things – not a bird but a model of a bird.

These artefacts (these ‘social constructs’, let us call them) are fabricated by other people, who are also living in the cave (not chained and constrained to see shadows only but nevertheless still in the dark).

These artefacts (these ‘social constructs’, let us call them) are fabricated by other people, who are also living in the cave (not chained and constrained to see shadows only but nevertheless still in the dark).

Plato is suggesting that there is more to these ‘images’ (I must try to find the Greek text: his word may well be ‘icons’) than there is to the shadows, but he is saying too that there are originals of these things that are mere representations.

Thinking in language, then, can be a liability. It is an aspect of the “unenlightened” condition that Plato proposed to discuss in this book of The Republic (book 7, at 514).

But what I mean by ‘thinking in language’ does not at all exclude thinking by language. Plato, here, is not turning against either language or images. His target is the error of taking darkness as disclosure: mistaking things that are mere ‘shadows’ or ‘images’ of something for the reality they are symbols of.

To think ‘in language’ is to satisfy yourself with that bit of language you come up with, in the meaning you attach to it, a move that is disastrous when the language is an image. ‘Sovereign’ is in fact an image word; it does not send you to the dictionary, it sends you to the world in which there are sovereigns.

To think ‘by language’ is to use the image word as the image it is, to read correctly. We could, of course, throw this opportunity away by being satisfied with the abstraction of ‘sovereignty’.

2 | An image of sovereignty, or sovereignty unveiled

To be an image of something is to be a window, made by an image maker, to see through: to look through and see the reality it was created in relation to, and created to reveal.

Image words direct the attention of those they are given to to the reality these words name, provided the recipient will receive them as image words and not the reality they name. Entrapment in language (which is in reality entrapment by, for example, laziness, or the pride of thinking ‘sovereignty’ says it all when it says almost nothing), versus the use of language as an instrument by which to know.

A sovereign is a king, and a king is not an abstraction. When language is abstracted, by which I mean stripped of its image dimension when it possesses such a dimension – we are led into a corner. Take the conception of the ‘sovereignty of God’, an expression that renders into a concept the claim ‘God is supreme’. Asked to explain what we mean by this, we might say, God is the supreme power, God rules over all. In doing this we are coming out of the corner, moving toward the characteristics of a king, and we should keep going, as these are not yet exhausted by the notions of ‘power’ and ‘ruling’ (indeed, the king has certain kinds of power and distinctive ways of ruling).

This is the sort of thinking that the language found in the Bible involves us in, providing we use that language:

the blessed and only Sovereign, the King of kings and Lord of lords (1 Timothy 6:15 ESV)

– use it and do not swap it for abstractions. These words are all signs pointing to the reality of the king, the highest earthly master.

It is a fact that, in their words about man and God, the authors of the Bible were drawing upon the submission of men before the living sovereign.

Let us kneel before the LORD, our Maker! (Psalm 95:6 ESV)

That is, they were acknowledging if not the logic of kneeling in the presence of the king (God forbid, we say today, thinking ourselves free of all kings) then at least the universality of this behaviour: whether governor or emperor or pharaoh, the sovereign power was entitled to deference.

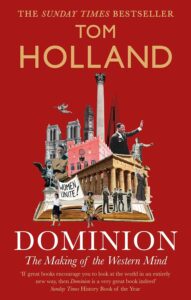

It is perhaps an irony, in fact, that the Christian Bible so thoroughly employs the image of not just earthly power but hierarchy itself, things that, says historian Tom Holland, Christianity has done so much to destroy. How can you kneel before a man to whom you are radically equal, and who is also another great sinner before God? It is the Christian tradition, Holland suggests, that has brought about our thorough rejection of earthly hierarchy: in what other tradition do we find the notion that no man deserves to be knelt before? (And yet, the saints.) If it is only before God alone that a man might kneel, it remains rather noteworthy that kneeling has disappeared from very many Christian churches – owing, apparently, to the conviction that earthly hierarchy squeezes in even here, in the churches, in the usurping of divine presence by worthless things (human functions and man-made idols). It is only the supremacy of God, we are told, that deserves recognition.

Our topic, however, is related to just that: the recognition of what is to be recognized in the sovereignty of God. What is our conception of supremacy? And how do we come to see the supremacy of God? In the Scriptures, it is partly by way of the image of the king.

3 | Dominion

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion! … Behold, your king is coming to you;….

In this text (prophesying the coming of Christ) the women of a land are called to anticipate the arrival of a conqueror who will overcome their foes and bring peace.

I will cut off the chariot from Ephraim and the war horse from Jerusalem; and the battle bow shall be cut off, and he shall speak peace to the nations; his rule shall be from sea to sea, and from the River to the ends of the earth. (Zechariah 9:9–10 ESV)

There is a description here of the character and extent of this “rule”. That is, there is more to say about this king than that he ruled and was sovereign. Skipping to another passage on Christ as king, chosen practically at random, we see this very same thing.

Then a mighty king shall arise, who shall rule with great dominion and do as he wills. (Daniel 11:3 ESV)

Dozens of times, in Old Testament and New, the Scriptures use a word translated as ‘dominion’, the word chosen by Holland for the title of his recent book about the rise of Christianity.

Dozens of times, in Old Testament and New, the Scriptures use a word translated as ‘dominion’, the word chosen by Holland for the title of his recent book about the rise of Christianity.

The ESV translation will sometimes render this as ‘rule’ (for instance, where the KJV has “his dominion shall be from sea even to sea” the KJV has “his rule shall be from sea to sea” – Zechariah 9:10). But often the ESV keeps this English word that we no longer use.

We used it not so long ago however. I was born in the Dominion of Canada; indeed, I still live in it, not that anyone cares to acknowledge this.

Dominion of Canada is the country’s formal title, though it is rarely used. It was first applied to Canada at Confederation in 1867…. Government institutions in Canada effectively stopped using the word Dominion by the early 1960s. The last hold-over was the term Dominion Day, which was officially changed to Canada Day in 1982 [during the reign of Trudeau père]. Today, the word Dominion is seldom used in either private or government circles.

Eugene A. Forsey & Matthew Hayday,

s.v. “Dominion of Canada,” The Canadian Encyclopedia (2006)

We can forego exploring why this loss occurred – and it is a loss. For good reason I liked this ‘Dominion’; I remember fondly the Dominion-store sign glowing in the dark, a patriot supermarket, and I enjoyed the days of ‘Miss Dominion of Canada’, all now gone.

To offer just one thought, might it have something to do with the fact, relevant to what we are examining, that a dominion involves domination. As the Scriptures mark repeatedly by the use of this word, dominion is mastery, manifest control, which cuts things off. Dominion is not just ruling (which can be done with impotence), it is dominance. Where the ESV reads, “the Philistines ruled over Israel,” the KJV delivers lexical emphasis: “for at that time the Philistines had dominion over Israel” (Judges 14:4). And the ESV sometimes follows this practice:

Then a mighty king shall arise, who shall rule with great dominion and do as he wills. (Daniel 11:3 ESV)

A king who can do as he wills is indeed “mighty” – and a king whose might reaches beyond all human power?

We know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him. (Romans 6:9 ESV)

‘Dominion’ refers to both the character of the power and the extent of its reach. When Isaiah writes, for instance,

there was nothing in [Hezekiah’s] house, nor in all his dominion, that Hezekiah shewed them not (Isaiah 39:2 KJV)

the issue is all the places in which this man was lord and master.

[]

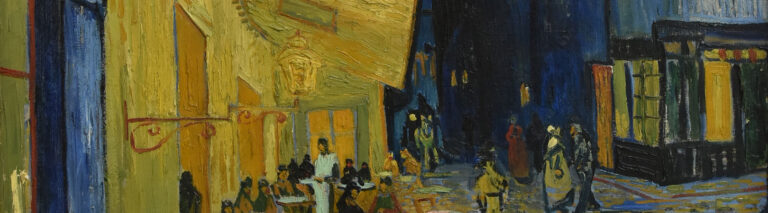

The image of Christ enthroned – here is one example from the Church of the Holy Spirit (Hagia Sophia) in Istanbul – is plainly an image of Christ reigning, and in this example the character and scope of his dominion is not greatly signalled in what we see. Scripture sets it out more fully than does the image.

The image of Christ enthroned – here is one example from the Church of the Holy Spirit (Hagia Sophia) in Istanbul – is plainly an image of Christ reigning, and in this example the character and scope of his dominion is not greatly signalled in what we see. Scripture sets it out more fully than does the image.

Yours, O LORD, is the greatness and the power and the glory and the victory and the majesty, for all that is in the heavens and in the earth is yours. Yours is the kingdom, O LORD, and you are exalted as head above all. (1 Chronicles 29:11 ESV)

It is the ‘exalting’ mentioned here that we are seeing. The word means “to raise high, to lift up; to elevate in rank, dignity, power, character” (Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 5th ed. [1949]). The Scriptural text, however, says Christ is exalted: that is, he is in this elevated state by virtue of his character, and in the church the position of the mosaic in an apse above our heads conveys exactly this. That the throne is enveloped in a sea of gold (actual gold foil sealed in small cubes of glass) sets this supremacy above anything human.

Heaven is my throne…. (Isaiah 66:1 ESV)

In this same image we also see Christ being exalted, which is a further aspect of his dominion: his exalted state is understood, by people, who do not just kneel but fall down before him. (Here it is quite significantly a Byzantine Emperor, Leo VI the Wise, who is bowed down.) To exalt is also “to extol, magnify, glorify” on account of the actual exaltation of the enthroned one. This is a dominion in which there is not just human deference to something higher but prostration before it.

Tom Holland’s book has two different subtitles: The Making of the Western Mind, in the United Kingdom, and, in America, How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. The Dominion of his title, which brought this about, is above all the submission of human beings to Christ that we see in the image at Hagia Sophia. A revolution, and the rise of the Western mind, are mere effects of Christ’s self-revelation. That is, the majesty of a king cannot compare.

O LORD, our Lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth! (Psalm 8:9 ESV)

3 | Supremacy

So the idea of ‘sovereignty’ or ‘kingliness’ unfolds, when it is allowed to unfold, into exaltation or supremacy. Christ is seen as high above us in magnitude and perfection.

Both riches and honor come from you, and you rule over all. In your hand are power and might, and in your hand it is to make great and to give strength to all. And now we thank you, our God, and praise your glorious name. (1 Chronicles 29:12–13 ESV)

Exaltation is height, being high, but in Christianity it is being high above man, to whom Christ has nevertheless come.

Exaltation, then, is not ‘lifting up’: we cannot lift anything so high. The exalted is supremely high, vastly higher than anything else we know, far above our standards and marks of achievement. This is, as it turns out, the meaning of ‘holiness’.

The Biblical meaning of ‘holy’ (qadosh | קדשׁ) is separated. There is a great distance between man and God. Scholar Chad Bird writes,

[God] alone is intrinsically and essentially holy. We sing of him, “You alone are holy” (Rev 15:4). Anything else called ‘holy’ borrows holiness from him.

Chad Bird, Unveiling Mercy (Irvine, Calif.: New Reformation Publications, 2020), 58

Joshua said to the people, “You are not able to serve the LORD, for he is a holy God” (Joshua 24:19 ESV) –

a being who eclipses all (is not even categorizable as a being). We could not possibly, with human powers, walk in the ways of God. The emperor is on his knees before Christ in his understanding of who Christ, as God, is: kneeling and prostration are visible acts that understand holiness and present that recognition to God and man, in honour of holiness.

In the very tradition that gave us the images in this essay, this exaltation/supremacy and holiness is of central significance. Indeed,

Orthodox tradition sees the Holy Spirit as hypostatized holiness

Tamara Grdzelidze, “Church (Orthodox Ecclesiology),”

in The Concise Encyclopedia of Orthodox Christianity,

ed. John Anthony McGuckin (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2014), 104

– that is, the holiness of God (the separateness, distinctness, supremacy of God’s divinity) takes, itself, the form of an entire person, a person united with God the Father and God the Son, and a person with whom human beings can have a relation (this being what a person is). When we think of the Holy Spirit we tend to emphasize, mentally, that this is the ‘Spirit’. But there are other and created spirits; what we appear to overlook is that this person of God is the Holy Spirit.

Christ was conceived by the Holy Spirit to save the world, “anointed” by the Spirit to do all the “things which he did” (Acts 10:38–39): proclaiming the gospel of His kingdom; calling people into that kingdom where he has dominion – calling them, that is, into his body, into the Church (which these church buildings all represent). And then when Christ ascended the disciples were given the Holy Spirit in which He Himself had acted, so as to continue His work.

It is because of holiness, which claims dominion over all things the supremacy of its apartness and distance, that churches came to have immense height. Hindu temples may be as tall as cathedrals, but their inner spaces, meant for worship, are low and quite small; they do not have interiors in which the person ‘in the church’ is drawn up, by eyesight – in a relation of vision – to what is high above them. To the sight of a face looking down to them, into their eyes.

If, then, we think of exaltation as ‘lifting up’ we are forgetting the greater part of its meaning, we are drifting from the essential. Man does not ‘lift God up’ to this height! This is the supremacy of the Lord.

‘Supreme’ is thus another word related to sovereign with a physical, spatial, significance that Christian art draws upon. It means “highest in degree, quality, etc.; not exceeded by any other”, and is derived from the Latin supremus, the “superlative of superus, that is above” (Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary). The God who remains above in His holiness remains there in his relation to us, to bring us into Him: into his holiness.

I recall a student once asking me, ‘Who are the saints; why should we care?’ If God tells His people,

Consecrate yourselves, therefore, and be holy, for I am the LORD your God (Leviticus 20:7 ESV),

then you can be sure that people will be carried over the vast threshold into His nature.

These are people who are not just exemplars of virtue; they are people brought by God into His exaltation. It is possible to strip the meaning out of what is meant by ‘glory’, ‘holiness’, ‘magnificence’, ‘supremacy’, and doing this not by emptying them, so that we hear nothing in these terms. We are too smart for that; we will always hear something. But it may be the concept that we have reduced ‘glory’ to. The result will then be to introduce counterfeits into our understanding of God, to replace the meaningful and the charged with the null and the dead. Our churches, structured and ordered by these images, were ways of rescuing us from that fate.

IN & OUT OF TIME

There is another side of the separateness of God, which concerns time.

To exist in time is also to live distanced from God, who is outside of time. We may have the impulse to resist this, saying that, no, God enters the world, to be, in time, with His people – but these are simply two Biblical claims in no contradictory relation, and one should not be used to cancel out the other. If the way in which God is present in your life is seen by a person as sufficient, all that anyone could want, then the plan that Christ came to carry out is unwanted by that person, and that would be an entirely paradoxical attitude for any Christian to hold. The churches that we are looking at all represented that plan.

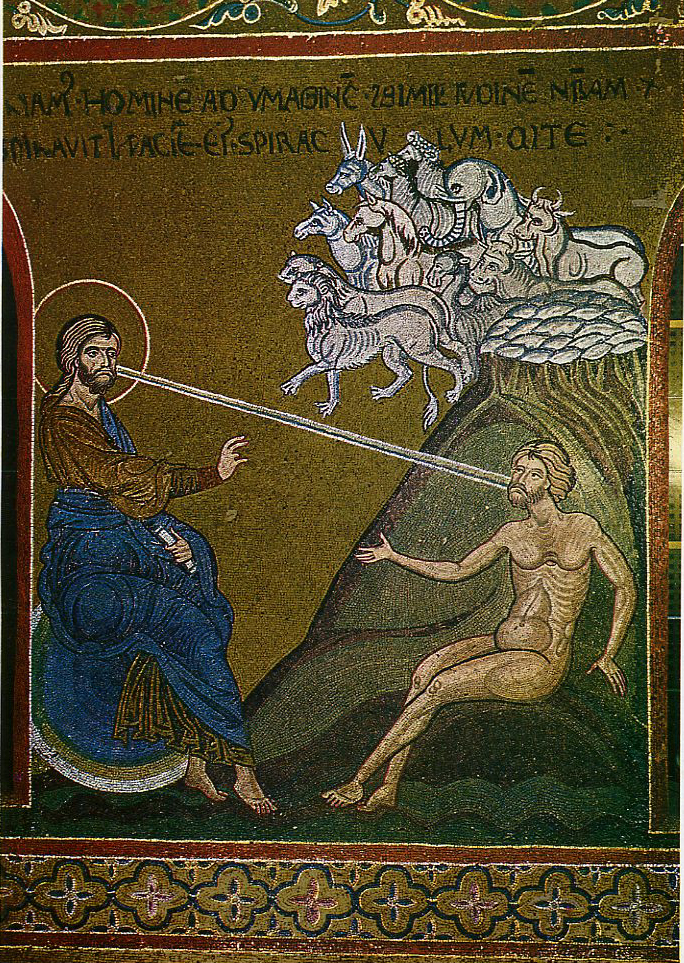

Christ reigns also over time. It was Christ who created time, in creating things that have a beginning, and it is Christ who was shown in images of Creation set out on the walls of churches – as shown below at the Cathedral of Monreale in Palermo.

We can register what is happening here in two steps: via the alpha and the omega, Creation and the new creation.

The Creation story was shown on church walls because God reigns over His Creation. Christ is the Creator. In the Creation of Adam (below) the first human being is blessed by the haloed figure of Christ (robed in blue and brown, the colours of heaven and earth, the earth that would form Christ Incarnate, the Second Adam).

The divine image that is imparted to man in his creation is loudly marked by a column of breath or spirit, a ray from face to face: man is an image of God. And from where does Christ operate in His work of creating?

He creates from outside place, which is generated in the Creation itself. What is the sphere on which he is shown sitting, this sphere that is his throne?

Heaven is my throne, and the earth is my footstool;…. (Isaiah 66:1 ESV)

On the seventh day, when He rests, Christ is shown again seated on this throne. All that He has done was done from ‘where’ He exists, but this is outside both space and time in His own ‘sphere’, as it were. At Monreale this is shown as the blue globe of the heavens, with on the seventh day the light (Christ’s energies?) withdrawn again into His centre (whereas in the preceding days it had been at the perimeter, touching the world). And in this scene of the day of rest a ring of red is added within Christ’s halo, in anticipation of the moment for which the stage is now set.

It is possible to think that nothing is lacking, for you, as a believer (assured of salvation, having seen Christ’s glory and opened yourself to it), but the building of this cathedral constitutes an image of a whole: the head at its highest place, with all the parts, all the organs joined to it, restored to life and functioning. And in the closing chapter of Isaiah, the chapter just quoted above, something greater than the life of any single part is announced.

The time is coming to gather all nations and tongues. And they shall come and shall see my glory,…. (Isaiah 66:18 ESV)

“All nations” … “shall see” His glory.

The supremacy of God as we see it in another Byzantine church (San Vitale in Ravenna) again seats Christ on His heavenly throne, exercising a rule or dominion that is eternal.

Your throne, O God, is forever and ever. (Psalm 45:6 ESV)

In this mosaic form the 6th century we are seeing a clean-shaven Christ, in the enduring style of the Roman empire; that it is Christ is unmistakable from the cruciform halo. In one hand He holds a scroll with seven seals.

Then I saw in the right hand of him who was seated on the throne a scroll written within and on the back, sealed with seven seals. (Revelation 5:1 ESV)

In the other hand is a crown (a golden wreath, the Roman style of crown), this being the exclusive sign of the emperor, the sovereign himself. But Christ does not seem about to wear it; rather he holds it out for someone else.

This is the primary image, at the front of the sanctuary, which the congregation would face. In this chapter of Revelation a crown is about to be handed out, an act that begins the events we link with the ‘four horses of the Apocalypse’, but in this setting of the church of San Vitale, it is clear that this crown is one we know of from elsewhere:

And when the chief Shepherd appears [i.e., at the Second Coming], you will receive the unfading crown of glory (1 Peter 5:4 ESV)

– this being the crown mentioned earlier in Revelation chapter 2:

Be faithful unto death, and I will give you the crown of life. (Revelation 2:10 ESV)

The significance of this is beyond extraordinary. The plan is to bring the members of the body of Christ onto Christ’s own throne to reign in glory with Him, on that throne of glory and magnificence, the very seat of holiness. The mortal human being is to be brought into the holiness of God and the apartness wiped away forever.

Standing in a church, looking up at the face of Christ in the dome, at the highest point (this example is the basilica of San Marco in Venice), or Christ enthroned in His place –

high above all nations, … his glory above the heavens! Who is like the LORD our God, who is seated on high, who looks far down on the heavens and the earth? (Psalm 113:4–6 ESV)

– looking up we are promised the closing of the distance now remaining, and assured by the watching face of Christ that now, even now, we are part of the fulfilment of time. That is, we are not simply in time, like everyone else; as members of the Church we are participating in what time is made for.

4 | Coming to see glory

Ordinarily the image of Christ on the throne of heaven is called Christ Pantocrator (if we use the language of Orthodoxy), while the habit in Western Christianity is to name this image Christ in Majesty. If the form of image is Byzantine in origin, it became established in the portals of the cathedrals and illuminated manuscripts of the West. The Eastern and Western versions of this one kind of image do not mean different things.

In the Greek name, ‘panto’ is from ‘pan’, meaning all, and ‘krator’ is from ‘kratia’ or power (as in democracy, demo-kratia or power of the demos, the people). Theologian Vladimir Llosky writes,

The iconographic type of the Christ-Pantocrator (Πατοχράτωρ, Ruler of all) expresses under the human features of the Incarnate Son, the Divine Majesty of the Creator and Redeemer, Who presides over the destinies of the world.

Vladimir Llosky & Leonid Ouspensky,

The Meaning of Icons (Crestwood, N.Y.” St. Vladimir’s Seminary, 1982), 73

The throne, Llosky notes, sometimes “does not appear”, “the type of the Christ-Pantocrator can always be reduced to a half-length image.”

It must by now be apparent how much of a mistake it would be to focus on concepts: terminology like All-Sovereign, Lord of All, Christ in Majesty, however correct they are, only touch on the reservoir of meaning contained in the Scriptural message that these images aim to set before the faithful.

Images, illustrated churches, were needed, it was thought, to put the follower of Christ back into the entire story and replace simplifications of that story (God is in charge of the world He made) with the astonishing reality that human thinking keeps wiping away. We know what it means to be in charge; we do not know what it means to be set on Christ’s throne. We know the meaning of power; we do not know and can never know, save by entering into a special and exalted state, the meaning of glory.

Churches without images leave the believer to gather into his or her own heart everything that is considered here, by reading the Scriptures instead of by images. On account of something that has gone wrong with our culture (which has sunk back into the cave), we have also tended to forget that reading the Scriptures is seeing through images. Texts such as those just mentioned (like Zechariah), we are told, must be read

By first allowing the images and symbols to activate the imagination, and then by exploring what those details symbolize.

ESV Study Bible (Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway Bibles, 2008), 1751

I don’t say that that is impossible, but why should it be so hard? Why should you each come with inner thoughts?

We are not abstract people: our language contains images: we are images of God who also see by images. Seeing helps us to live.

Neither are we interior people; if we are a people we live in space, among others. Why not put not the words of Scripture but the meaning of these astonishing Scriptures on the walls, so that Christians may, and together, understand what they are living, here in the image of the body of Christ? How can we think ourselves free of all kings (!) when there is one king who is the King of Kings? How can shedding earthbound behaviour make us shed heaven-bound behaviour? Kneel, and be prostrate even, before the Christ whose arms reach out to us, in the curvature of the apse, to gather us into His own holy state?

.

Works

Church of the Holy Spirit (Hagia Sophia), Istanbul

narthex mosaic over Imperial Door | c. 900

photo Feng Wei on Flickr

Holy Monastery of Zografou, Mount Athos

cupola mosaic

photo Dimitris Sotiropoulos on Flickr

Basilica (Cattedrale di Santa Maria Nuova), Monreale, Palermo, Sicily

apse & nave mosaics | 1174–89

photo (apse) Anura on Flickr

photo (nave) heffelumpen9 on Flickr

Church of San Vitale, Ravenna

apse mosaics | between 546 & 556

photo Cecilia Condal on Flickr

Basilica San Marco, Venice

cupola mosaics | 12th to 13th C

photo Steven Zucker on Flickr

Christ in Majesty, Santa Maria del Mur, Spain

apse fresco | 12th C

photo Bob on Flickr