“I meditate on all thy works” | William Holman Hunt’s Our English Coasts

As this is a long read, a summary may help you gauge your interest.

• HOW IT WAS THOUGHT THAT SYMBOLISM IN ART & AN ART THAT INSTRUCTS WERE BAD FOR US, UNDER THE INFLUENCE OF PHILOSOPHICAL JUDGEMENTS CONCERNING REALITY & FACT

• HOW MODERN PROTESTANTS LINKED THE FADING OF SYMBOLISM WITH A HEALTHY PROTESTANTISM

• & HOW ONE ARTIST REJECTED ALL OF THIS AS NONSENSE – A VERDICT TO WHICH WE GIVE THE SUPPORT OF CALVIN, TO SAY NOTHING OF SCRIPTURE

1 | Rejected: symbolic art, an art of ideas, art that ‘points a moral’

What happened to sacred art, and when? Suppose that we believed, with the scholar Titus Burckhardt, that

Every sacred art is founded on a science of forms, or in other words, on the symbolism inherent in forms.

Titus Burckhardt, The Foundations of Christian Art

(Bloomington, In.: World Wisdom, 2006), 1

In the 19th century arguments were made against symbolism in art. (I don’t mean to say that this is the beginning of anti-symbolism, rather that this age will be our focus.)

Or consider the matter from a slightly different angle: how did the view that art is cultural – being

a means of expressing ideas of great moral or theological importance,

Unsigned, “Allegory in Art,”

The Crayon 3:4 (April 1856), 114

as a way of cultivating people endowed with such ideas – fall into disfavour, as it does with this author.

I am quoting an essay of 1856 in the American art magazine The Crayon, where this view of art is dismissed as a misunderstanding of the very purpose of art: morality is one thing, art another. Moral instruction and art are separate “arts” and it is a elementary mistake to make

one Art attempt to perform the offices of another. This, it seems to us, is the case in allegoric Art, where it is attempted “to point a moral or adorn a tale” by painting, and we should characterize such an attempt as a departure from the position in which Art is strongest, because [it is] at home.

Art, we are told, has strength in its own domain, the visual –

the office of painting is with the visible world

“Allegory in Art,” 114

– and it undermines itself when it strays from its territory

to assume [the work] of a teacher in a sphere where words can act far more economically and effectively.

In short,

There is a degradation of the Art involved in making it the servant either of ethics or theology.

“Allegory in Art,” 114

To this writer, art’s dabbling in these domains does actual damage to culture: whatever it achieves it does

a greater, if more remote, evil, by obscuring the true standard of Art, and making us forget what its proper functions are.

“Allegory in Art,” 114

TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY BELIEFS

I expect you will appreciate that these are 21st-century beliefs – they are views of the 19th century that held their ground.

Make a list of ‘brick-and-mortar moral institutions’ – that is, institutions sprung direct from a moral outlook but that have walls on which to put something, something to look at – and if such a list is hard to make just transport yourself back to the 1850s. Churches, law courts, schools of all kinds – even hospitals, cemeteries, and especially homes. (Listing these is an interesting exercise that could distract us considerably; we might think every structure worth building has a moral justification – sports arenas, factories, parks, … – but we must move on to our point.) Those institutions that in the 21st century are still counted ‘moral in character’, still accepted to be ‘aligned with something people must be taught’ – churches, for instance – are often now bare.

If you find anything on their walls it is very likely to be words, which the unnamed critic I cited judged “far more effective” at instruction than anything achievable by images. (In a banner that magnifies the word ‘hope’, accompanied by a schematic candle, it is the word that does the work; remove it and the candle does not say ‘hope’.)

The above-described view of art and symbolism has triumphed and our question is why? What has succeeded in driving people, even Christians, to think in this way?

A REALITY OF FACTS

Another Victorian writer, speaking of his day, said, in effect,

the character of the age is foreign to symbolism.

George P. Landow (on William Michael Rossetti),

in William Holman Hunt & Typological Symbolism

(New Haven: Yale University

Press, 1979), 27

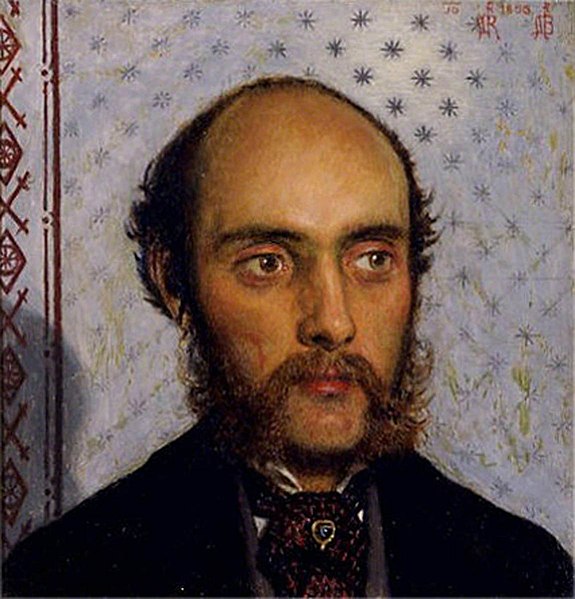

The reference is to William Michael Rossetti, brother to the painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the poet Christina Rossetti. In an essay on “The Externals of Sacred Art” Rossetti noted that

The motto of the practical man ‘Facts and Figures’ may be made to serve his turn for pictures…. Indeed, we may put it to … most readers whether they are not themselves cold to typical [i.e., typological] art of the present day,

W.M. Rossetti, “The Externals of Sacred Art,”

The Crayon 5:12 (December 1858), 334

or such symbolic art as continued to be made (less and less).

Rossetti still uses the word ‘typical’ in the old way, as relating to typology, because the concept of typology still had genuine currency in thought through its (important) connection with the Bible. We, however, need a slight reminder of this.

The Apostles, evangelizing to the Jews, interpreted the Jewish scriptures, and did so in ways that Jesus had employed, very often

min[ing the texts] to find predictions of the work of Christ and the Church. Their method was that of typological interpretation – to find events, objects, ideas, and divinely inspired types (i.e., patterns or symbols) represented in the Old Testament that anticipate God’s activity later in history. The assumption is that the earlier event/object/idea repeats itself in the later one.

Introduction to Biblical Interpretation, 3rd ed.,

ed. William W. Klein, Craig L. Blomberg,

& Robert L. Hubbard, Jr. (Grand Rapids, Mich.:

Zondervan Academic, 2017), 78

(For instance, consider the relation between the sacrifice of Isaac in Genesis and John 3:16, or take the Old Testament figures who, said medieval Christians, “signified Christ” by their actions.)

Replicated in art, Rossetti argued, this signifying would no longer work.

The artist, who works with the aim of impressing the mass of his contemporaries … will find his wisdom to leave the type [symbol], and hold to the direct fact.

W.M. Rossetti, “Sacred Art,” 334

(For ease of comprehension in what follows where Rossetti wrote ‘typical’ I will just substitute ‘symbolic’.) On this view Landow writes,

Here as in most of his other critical writings … Rossetti opposes symbolic and realistic painting, believing the two are intrinsically incapable of being combined.

Landow, 27

Modernity is unsuited to symbolism; sacred art must depict ‘facts’. But what are these ‘direct facts’ – and art must cleave to them why? Part of the answer is the ‘metaphysics’ that people had tacitly adopted, the conception of reality they were as the only one a modern person could accept.

WHAT MAKES REALITY REAL

Landow puts it this way.

Once men began to accept that reality, the Real, inhered in the visible, the here and now, older notions that some higher realm possessed a greater reality quickly lost force and eventually all but vanished.

Victorian writings on both art and literature demonstrate that the basic attitudes necessary to a living allegorical art had long vanished, for the changing attitudes toward external reality which led to the rise of realism [in art] destroyed the relevance of symbolism for most critics and painters.

Landow, 27

A new paradigm of realness had arisen that was fatal to symbolism, a paradigm not only foreign to but dismissive of Old and New Testament thinking about the nature of reality, in its elevation of “the things that are unseen,”

For the things that are seen are transient, but the things that are unseen are eternal.

2 Corinthians 4:18 ESV

Without ever dismissing these words of the Apostle Paul, we have taken on distinctions that are out of step with this Biblical ‘metaphysics’. (The Bible teaches no metaphysics, we say, so our metaphysical presumptions create no conflict.) One of these presumptions concerns the scope of fact.

TRUTH & FACT

There are indeed facts, but when the truth becomes factual it is not accepted but rejected: all the truth not amenable to the conditions that deliver the ‘fact’ winds up dethroned.

W.M. Rossetti proposed that sacred art adhere to “direct facts”, because only thus could he deliver what the public could accept – so what, then, are facts?

We use ‘facts’, often, to mean undeniable realities. A person who says ‘You may not believe it … but it’s a fact’ might simply be saying but it’s true, yet it is quite likely that she means something more (since to counter ‘it’s true’ is too weak, is mere contradiction). The modern person means it’s factually true: that is, not just true but true in some demonstrable, irrefutable way. This is a modern sense of the word.

The original sense of the word had no such substance, carried no sense of any quality of proof. A 19th-century figure like

Matthew Arnold almost invariably uses the word in its normal 19th-century sense, which is also our modern one, as the term for something that is ‘demonstrably the case’ in what he conceives of as an objective and scientific sense. Yet its original meaning in the 16th-century (the OED lists its first use in 1539), reflecting its Latin root, factum, was ‘a thing done, or performed’, making it cognate with ‘feat’ – a use that had persisted alongside the later meaning until the beginning of the 19th century.

Stephen Prickett, Words and The Word:

Language, Poetics, and Biblical Interpretation

(Cambridge University Press, 1986), 192

The modern concept of ‘factuality’ engages a new concern with the basis of conviction and suggests a new paradigm for conviction: as a result, the power of an art of fact will outstrip any art of symbol.

What is the power? Fact in the modern and still current sense means

what has actually happened or is the case, truth attested by direct observation or authentic testimony, reality.

S.v. “Fact”, sense 6, A New English Dictionary

on Historical Principles (Oxford:

The Clarendon Press, 1901), vol. 4

Note the examples of this gathered in the OED. In the case of material

collected from experience and present matter of fact

(an example from 1736)

the thing is presently verifiable via direct experience; and when a person says,

This case of deliverance from the pangs of guilt is fact

(from 1836)

what decides the matter is that the pangs of guilt are no longer experienced. In a related definition, ‘fact’ per se is

something certainly known to be of this character, hence, a particular truth known by actual observation or authentic testimony (as opposed to what is merely inferred, or to a conjecture or fiction), a datum of experience as distinguished from the conclusions that may be based on it.

And, crucially, this “datum of experience” must be publicly accessible.

Facts are more powerful than arguments.

(from 1782) s.v. “Fact”, sense 4,

A New English Dictionary

on Historical Principles, vol. 4

BUT IF FACTS ARE SEEN SYMBOLS ARE READ

I am looking at this because we are discussing symbols. The meaning-carrying sign is there, in a ‘factual’ way, but the meaning the sign bears must be seen in it. As Wittgenstein noted to ‘see the sign as’ something (to see the written character as a sound, to see the cloud shapes as a dragon) demands something from the interpreting person.

To interpret is to think, to do something; seeing is a state.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

(Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1958), 212

But ‘to think’ might be more than making mental connections – or rather, it might be openness to the connections, of a sort that allows them to be made.

Here, finally, is the upshot of the modern attraction to fact.

When a society favours factual truth over other modes by which the truth is seen – (is truth the fruit of interpretation?

‘Seeing as …’ [i.e., interpreting] is not part of perception. And for that reason it is like seeing and again not like)

Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, 197

– that society is already forgetting those other modes, ceasing to believe in them, and beliefs not based in fact can fall away (‘exposed’ as baseless).

But it is not just belief that vanishes with the rise of fact. Instruments of culture also disappear as the culture is updated, made more ‘rational’. We are looking here at the 19th-century’s own justification for replacing symbolism with what it called “naturalism”, for the restriction of ‘moral formation’ to words. What vanishes are beliefs, cultural practices, and the culture those practices had built.

3 | Naturalism

Another reason given for “19th-century coolness to pictorial symbolism” (Landow, 27) was that symbols must be interpreted (we must discern what the symbol means). In his essay W.M. Rossetti, presuming to write for

a Protestant people of the nineteenth century,

W.M. Rossetti, “Sacred Art,” 333

notes the decline after the Reformation of … not interpretation but interpretation in a tradition. The cause of the rejection of symbolism is not Protestantism; it is not so simple – but it would be obtuse to ignore the way that this Protestant links interpretation trouble with what he calls Protestant individualism. (Ignore this and you miss the chance to challenge his conception of what Protestantism demands.)

Rossetti was Anglican. Though his father had come from Catholic Naples the family he formed in London belonged to the Church of England, an Anglicanism unaligned with Roman Catholicism (as per

the thoroughly Protestant spirit which runs throughout the “Articles of Religion”

“J.C. Ryle on the 39 Articles of Religion”

in the back of the Anglican Prayer book. As for the Rossetti family it is notable that the Catholic painter James Collinson, hoping to marry Christina Rossetti,

in deference to her scruples … converted to Anglicanism, but a deep pang of conscience sent him back to Catholicism and lost him Christina.)

Makers of Nineteenth Century Culture,

1800–1914, ed. Justin Wintle (London:

Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982), 524

In the wake of the Reformation, writes William, symbolic art declined.

In its present decadence [it] has ceased to form any broadly considered and recognizable system. But this fact is itself an element of Protestantism; it [Protestantism] has broken from tradition, and asserts the individual.

W.M. Rossetti, “Sacred Art,” 334

That is, interpretation fragmented – justly, so – owing to Protestantism’s proper defense of “the right of private judgement” (Luther’s reading of Scripture contra his tradition, etc.). Symbolism divides, Rossetti is saying. Were Protestant artists to engage in it,

here the artist has to select and combine his own symbols,

and the odds will be that, as a result,

he aims … at the expression of some religious idea which the beholder is not disposed to receive; or, even if they are at one regarding the idea, he has embodied it under a form … for which he is individually responsible. He has asserted in the process his own Protestantism, or right of private judgment; and the more definitely and more originally the assertion is made, the less avenue has he opened for himself towards the convictions and the acceptance of others.

W.M. Rossetti, “Sacred Art,” 333–34

Thus a Protestant art that was symbolic would not be communal; sacred art for “a Protestant people” requires “naturalism”.

NATURALISM & LITERAL NARRATIVE

Naturalism, in connection with sacred art…, implies and prescribes a prevalence of direct or narrative over symbolic representations…. The narrative form of sacred art is in conformity with the feeling of the time…. The two most distinctive characteristics of Protestantism may perhaps be defined as the assertion of the right of private judgment (or, more strictly, the irresponsibility for private judgment save to God alone), and reverence for the Bible. These two qualities in combination naturally predispose the mind to receive gladly any conscientious and heartfelt representation of scriptural history, in which the aim is to adhere strictly to the recorded fact, merely transferring it from verbal expression to form and depending for its impressive enforcement upon the fidelity of the transcript.

(That is, it was sufficient to illustrate the historical events of the Bible, and do so accurately.)

This neither adds aught to the Bible nor diminishes from it, and makes no sort of demand upon the beholder’s private judgment in dependence upon the artist’s. The direct Bible narrative is the arbiter appealed to by both.

W.M. Rossetti, “Sacred Art,” 333

Rossetti drew attention to the problem (by now a real problem) of the artist fabricating his own symbols (think for example of William Blake), symbols inaccessible to the public that art was for – a problem manifest once artists had become autonomous creators answering to individual genius. The solution to this problem was naturalism, factually correct Biblical illustration, the literal depiction of undisputed events with a material and phenomenal character. Biblical reality conveyed in Biblical facts.

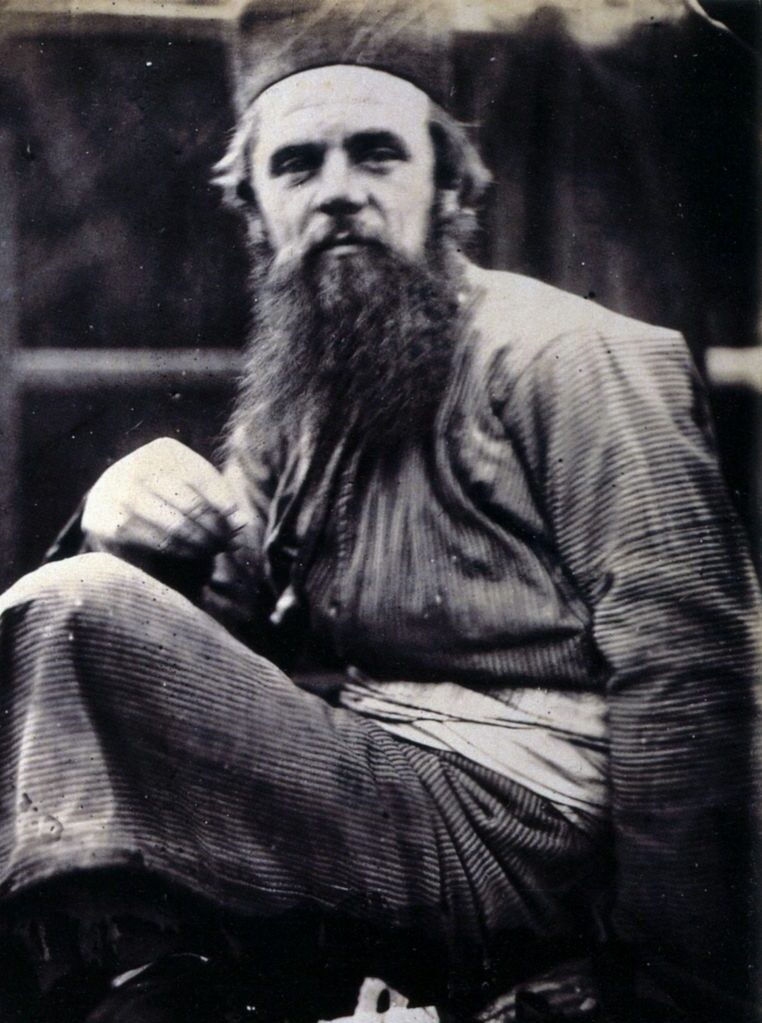

4 | Against these falsehoods

These new views were rejected by the artist William Holman Hunt, one of the founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, because each of these views was and is false. In emphatic opposition to them, writes the art historian George Landow, it was Hunt’s ambition

to revive the capacity of painting to convey important truths of mind and spirit at a time when the existence of these truths was in dispute…. Increasingly, artists of the past century

(Landow, writing in 1979, means 20th-century Modernists)

have tried to solve the difficulties created for painting by doubt and disbelief with an art that makes no reference beyond itself. Placing black squares on a black ground may not say anything true about anything beyond the way we perceive in a specific context – but then it

does not say anything false either. The painting of William Holman Hunt, in contrast, makes explicit, detailed reference to both material and spiritual worlds; for he refused to accept the loss of belief, the cultural fragmentation, and the sheer lack of confidence that made the Victorians the progenitors of the modern age. Considered in the context of Pre-Raphaelitism, then, he was the arch conservative who, for all his bitter hatred of the medieval revival, came closer to creating an art suited to the Middle Ages than anyone else. His art stands at one pole, while that of Rossetti and Burne-Jones stands at the other:….

George P. Landow, William Holman Hunt

& Typological Symbolism (New Haven:

Yale University Press, 1979), 1–2

We could examine quite a few pictures by Hunt in order to explore this, pictures that, in what they present, repudiate every part of the critique of symbolism we opened with. We will look at only one, a painting that, like others he made, affirms instead the following counter-positions:

- reality is not visible reality;

- the physical world bears symbolic meaning –

- indeed just as the Scriptures tell us;

- and chaos in interpretation arises just when the artist employs “his own symbols”, rejecting the language of symbols created by God.

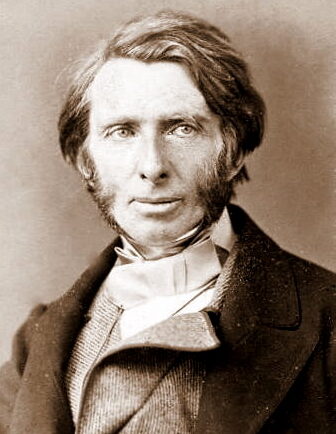

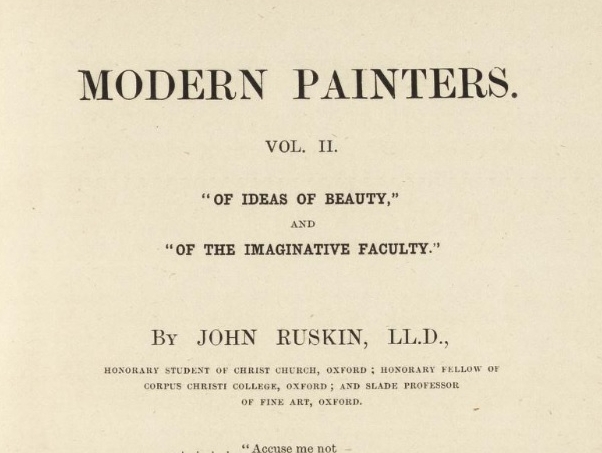

HUNT’S ASTONISHMENT AT RENAISSANCE SYMBOLISM

In a memoir of his career Hunt discusses, twice, the impression made on him when as a student he read John Ruskin’s account of an Annunciation by the Venetian painter Tintoretto. Reading volume 2 of Ruskin’s Modern Painters (1846), was, Hunt said,

In a memoir of his career Hunt discusses, twice, the impression made on him when as a student he read John Ruskin’s account of an Annunciation by the Venetian painter Tintoretto. Reading volume 2 of Ruskin’s Modern Painters (1846), was, Hunt said,

an event of the greatest importance.

William Holman Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism

& the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

(London: Macmillan, 1905), vol. 1, 73

Five years before his death Hunt could still recall

the little bedroom … wherein I sat till the early morning reading [this] passage with marvel.

Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism & the PRB, vol. 2, 262

To get through the book I sat up most of the night,…. But of all its readers none could have felt more strongly than myself that it was written expressly for him.

Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism & the PRB, vol. 1, 73

The book’s significance was twofold. First, Hunt found there a defense of his own conviction that contemporary art was “moribund”. Ruskin had articulated the belief that

the beauty aimed at now is exactly the opposite to that of great art: in old days the ambition was to combat sickly ideas of beauty; the modern ambition is utterly without health or force of character, either physical or mental. It is conceived to satisfy the prejudices of the modiste; ladies … are portrayed with waists that would condemn the race to extermination in two generations, and men are made such waxwork dandies that savagedom would soon sweep a nation with such an aristocracy into the melting-pot. Art’s office is not to encourage such maudlin culture,….

The true purpose of art was cultural – to cultivate:

to raise aspirations to the healthy and heroic; it certainly should not lead its admirers to court the moribund, by decking up the sentimentally languid in fine feathers. Lately I had great delight in skimming over a certain book, Modern Painters …; it was lent to me only for a few hours, but, by Jove! passages in it made my heart thrill. He feels the power and responsibility of art more than any author I have ever read.

And at just this point in his memoir Hunt turns to Ruskin’s eye-opening reading of of Jacopo Tintoretto’s (1518–94) Annunciation, the book’s second “marvel”.

We will skip the full story of this, fascinating though it is given the unusual fact that, decades later, Hunt and Ruskin would stand side by side in Venice looking at this very painting and Ruskin would reveal, by the way in which he spoke of it, that he had become an atheist. But Ruskin had earlier impressed Hunt with a vision of the role of art.

We will skip the full story of this, fascinating though it is given the unusual fact that, decades later, Hunt and Ruskin would stand side by side in Venice looking at this very painting and Ruskin would reveal, by the way in which he spoke of it, that he had become an atheist. But Ruskin had earlier impressed Hunt with a vision of the role of art.

He describes pictures of the Venetian School in such a manner that … you feel that the men who did them had been appointed by God, like old prophets, to bear a sacred message, and that they delivered themselves like Elijah of old.

Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism & the PRB, vol. 1, 89–90

THE ABANDONED TRADITION OF SYMBOLISM

That second marvel was Ruskin’s explanation of the traditional use of symbols. In Ruskin’s exposition of Tintoretto’s Annunciation Hunt saw for the first time what the earlier use of symbols in painting had been, and this handed to Hunt

the inspiration for his ambitious attempts to bridge realism and symbolism…. The typological symbolism which Ruskin explained came as a revelation to Hunt, since it solved the artistic problems that had been troubling him. The symbolism … strikes the informed spectator as a natural language inherent in the visual details themselves.

Landow, 2, 4

Turn now to a work that Hunt painted under the influence of this enlightenment.

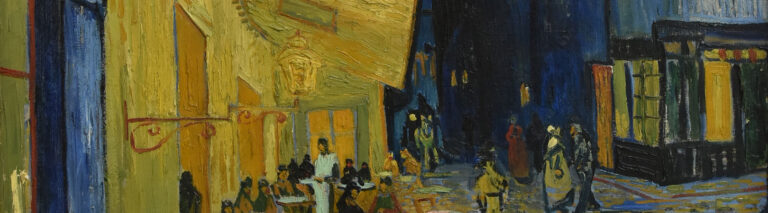

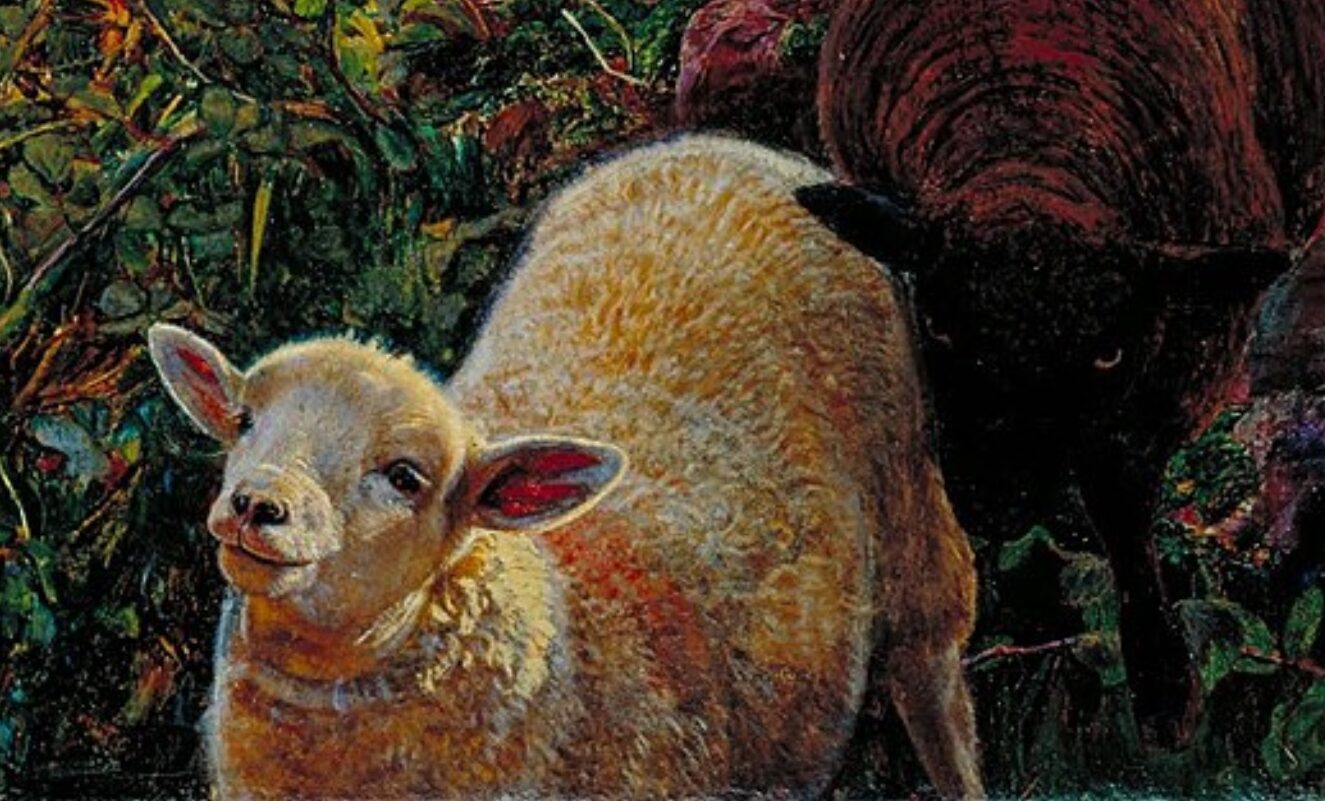

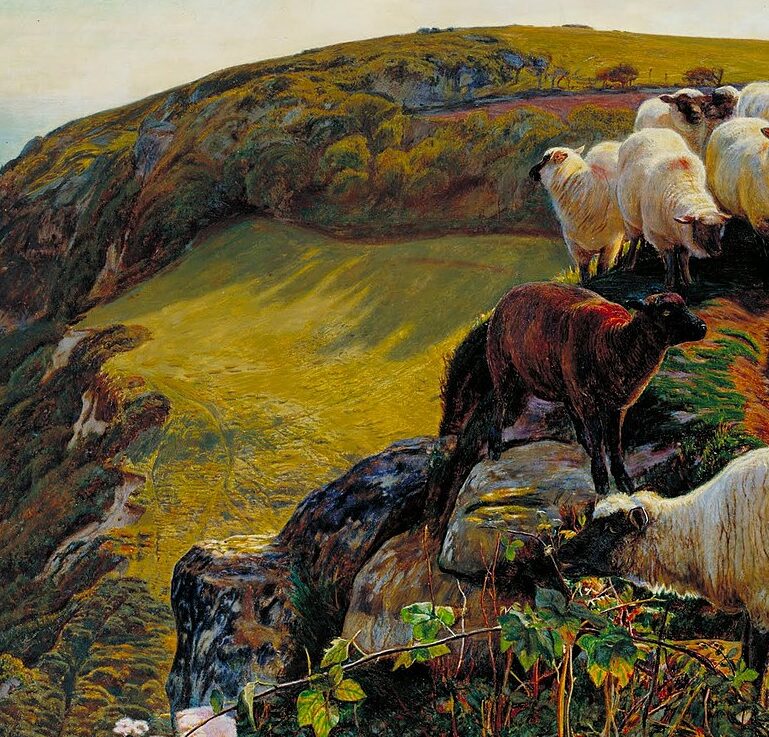

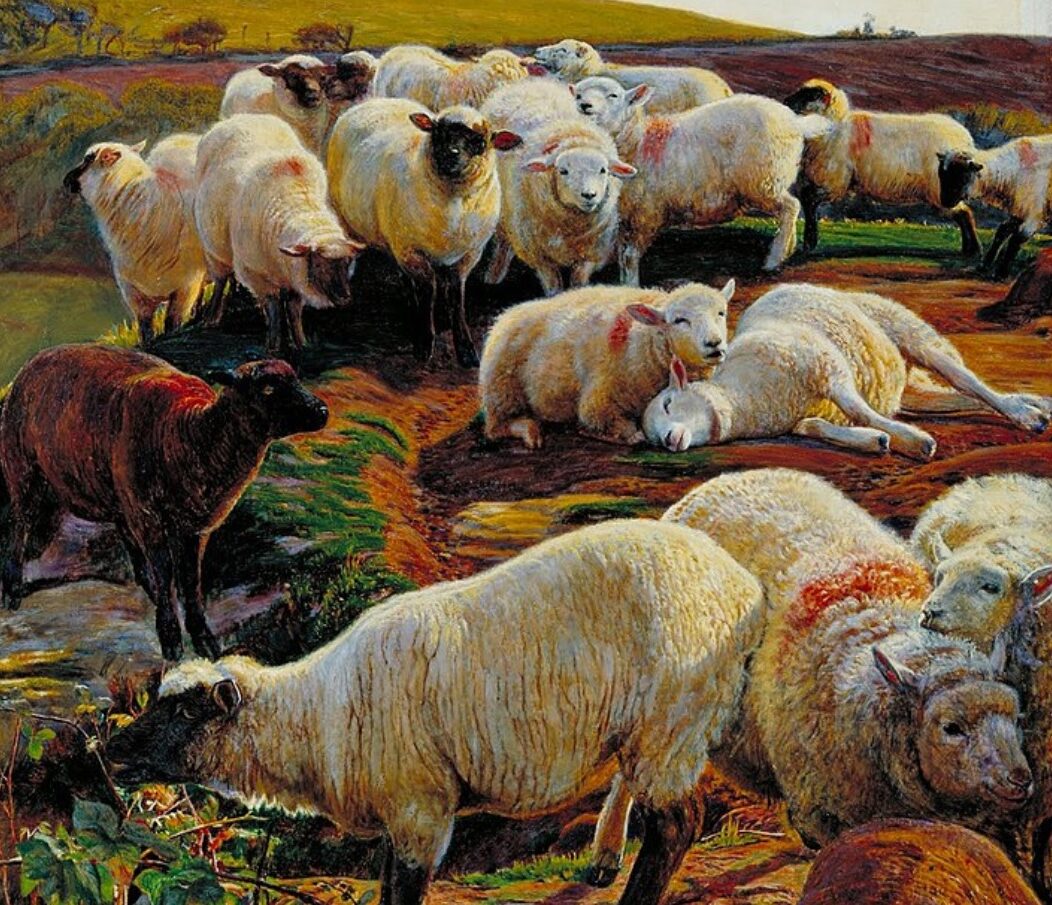

4 | “I meditate on all thy works”

The painting that Hunt exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1853 was labelled there Our English Coasts (exhibited paintings had titles in part so they could be discussed in the newspapers, these exhibitions being

major public events), a title that suggests a landscape and indeed you might call it one. It is, writes art scholar Allen Staley in The Pre-Raphaelite Landscape,

a sunlit view of a recognizable spot on the South Coast of England,

a painting devoted to the glow of sunlight, which had been a focus of great names in the history of landscape (Cuyp, Lorrain, Turner). However, Hunt’s

sunlight does not dissolve objects but emphasizes their particular qualities. It glows through the thin membranes of the sheep’s ears, and it illuminates each leaf blossom and butterfly separately.

Allen Staley, The Pre-Raphaelite Landscape

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 79

The sun not only lights the scene but has a kind of penetrating and revealing quality. If the sunlight, here, is not just a quality of the landscape but in fact a kind of entity you would have in Hunt’s picture an expression of sunlight echoing something older. As Hunt stated in his memoir,

The sun not only lights the scene but has a kind of penetrating and revealing quality. If the sunlight, here, is not just a quality of the landscape but in fact a kind of entity you would have in Hunt’s picture an expression of sunlight echoing something older. As Hunt stated in his memoir,

the first principle of Pre-Raphaelitism was to eschew all that was conventional in contemporary art, … [to adopt] a child-like reversion from existing schools to Nature herself.

Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism & the PRB, vol 1, 125

It is possible to go back “to Nature herself” in all of her symbolic power. Naturalism and symbolism are in no way dichotomous.

LANDSCAPE, BUT WHAT IS LANDSCAPE?

Were you or I to answer the question What is a sunny day, our response could be powerfully simplistic, the impoverished offering of a flattened soul – a soul not predisposed to evil but stupidly dedicated to radiating its own dullness, its blindness and inattention. But it is possible that the very same soul has spark enough to recoil from this habit. There is a disjunct between the world we picture to ourselves, in our concept-language, and the world we know in other ways. – What was a sunny day to St. Francis, for example? (Here another Venetian Renaissance painting awaits our examination.)

When in 1883 Ruskin gave a set of lectures on English painting he began his series with Hunt – in fact with this very picture – contrasting it with past landscapes, in which the light does not show colour.

Claude’s sunshine is colourless – only the golden haze of a quiet afternoon – so also that of Cuyp….

John Ruskin, The Art of England: Lectures

Given in Oxford in The Two Paths, etc.

(Boston: Aldine Book Publishing, 1883-84), Lecture 1, 260

When Ruskin says,

this picture, were it only the first that cast true sunshine on the grass, would have been in that virtue sacred,

Ruskin, The Art of England, 261

he is speaking of something that he cannot express, and he takes pains to show that what he cannot express is nevertheless vastly real: knowable. His explanation is worth reading right to the final line.

he is speaking of something that he cannot express, and he takes pains to show that what he cannot express is nevertheless vastly real: knowable. His explanation is worth reading right to the final line.

I cannot say of this power of true sunshine, the least thing that I would. Often it is said to me by kindly readers, that I have taught them to see what they had not seen: and yet never – in all the many volumes of effort – have I been able to tell them my own feelings about what I myself see. You may suppose that I have been all this time trying to express my personal feelings about Nature. No; not a whit. I soon found I could not, and did not try to. All my writing is only the effort to distinguish what is constantly, and to all men, loveable, and if they will look, lovely, from what is vile, or empty – or, to well trained eyes and hearts, loathsome – but you will never find me talking about what I feel, or what I think. I know that fresh air is more wholesome than fog, and that blue sky is more beautiful than black, to people happily born and bred. But you will never find, except of late, and for special reasons, effort of mine to say how I am myself oppressed or comforted by such things.

This is partly my steady principle, and partly it is incapacity. Forms of personal feeling in this kind can only be expressed in poetry; and I am not a poet, nor in any articulate manner could I the least explain to you what a deep element of life, for me, is in the sight merely of pure sunshine on a bank of living grass.

Ruskin, The Art of England, 260

It is on account of this reality, which Hunt has let into his painting, that Ruskin says of that painting that,

in its deeper meaning, it is … the first of Hunt’s sacred paintings – the first in which, for those who can read, the substance of the conviction and the teaching of his after life is written,….

Ruskin, The Art of England, 261

When Ruskin writes that,

Standing long before the picture, you were soothed by it, and raised into such peace as you are intended to find in the glory and the stillness of summer, possessing all things,

Ruskin, The Art of England, 261

the final words mark what “the glory and the stillness of summer” signify, because the creation of summer has meaning.

SHEEP, BUT NOT SHEEP

At the same time we have the sheep, neither the animals nor the landscape being the focus.

The painting had been commissioned by a man who had liked the sheep in Hunt’s The Hireling Shepherd, painted a year earlier, but who could not afford that painting. Hunt agreed to paint him something affordable, foregrounding sheep. Of the picture he painted, however, it was noted immediately that it was

of men, not of sheep.

F.G. Stephens, William Holman Hunt &

His Works: A Memoir of the Artist’s Life,

with Descriptions of His Pictures (1860), 23

In his memoir Hunt refers to the picture, in the year of its creation, not by its exhibited title but as Strayed Sheep, so this is also a Biblical picture, alluding to a Biblical verse. You could ask, as it is often wise to do of Christian pictures, what Biblical verse is its source, but the beauty of this image is the way it works with many verses. In his Oxford lectures Ruskin ended his discussion of it with lines from Isaiah 53:6:

“All we like sheep have gone astray, we have turned every one to his own way, and the Lord hath laid on Him the iniquity of us all.”

Ruskin, The Art of England, 261

‘Strayed sheep’ – the concept – is a Biblical metaphor, and the painting gives us a literal depiction of this concept: we are looking at an illustrated metaphor.

And Jesus, when he came out, saw many people, and was moved with compassion toward them, because they were as sheep not having a shepherd:….

Mark 6:34 KJV

“If a man has a hundred sheep, and one of them goes astray, does he not leave the ninety-nine and … seek that which is gone astray?

Matthew 18:12 ESV

Are we not seeing this sheep, that one that has gone down into the brambles, near the very edge of the cliff, where the edge is concealed by wildflowers? Then we see others crowded in a bunch in the middle distance, again right at the limit of the hilltop, clustered in such a way that sheep at the right, if they crowded a little, might send one at the left right over the side. And then there is the brown sheep in the centre, standing with its back to the precipice.

Are we not seeing this sheep, that one that has gone down into the brambles, near the very edge of the cliff, where the edge is concealed by wildflowers? Then we see others crowded in a bunch in the middle distance, again right at the limit of the hilltop, clustered in such a way that sheep at the right, if they crowded a little, might send one at the left right over the side. And then there is the brown sheep in the centre, standing with its back to the precipice.

Like sheep we gravitate to the edge, the edge of perdition. There is an entire expanse of green to graze in, furnished for them by their owner – we can see it far below – but here they are.

Like sheep we gravitate to the edge, the edge of perdition. There is an entire expanse of green to graze in, furnished for them by their owner – we can see it far below – but here they are.

It is owing to that “eloquence of things” and events that we touched on in essay 2 that this sheep behaviour says something. And there is more in the image than the sheep.

THE UNSEEN PRESENCE

Also visible in this picture is the unseen presence (I am not sure how else to put it). It is possible to paint an invisible presence, by not painting it but rather the response to it.

Most of the sheep (at least half) are turned in your direction, as it were, eyes on … something of a man’s height, and to this we might say, Of course, when Hunt was sketching them they looked at him. But this is not a photograph; Hunt needn’t have drawn or painted those sheep, he might have painted only oblivious sheep.

Most of the sheep (at least half) are turned in your direction, as it were, eyes on … something of a man’s height, and to this we might say, Of course, when Hunt was sketching them they looked at him. But this is not a photograph; Hunt needn’t have drawn or painted those sheep, he might have painted only oblivious sheep.

The sheep hear his voice, and he calls his own sheep by name and leads them out.

John 10:3 ESV

On the hilltop the sheep have cropped the growth down to nothing; what there is to eat at this spot is the wild growth over the edge, and it is there, we can see in the foreground, that the shepherd is standing.

I will seek the lost, and I will bring back the strayed,….

Ezekiel 34:16 ESV

In this verse from Ezekiel we have the ‘lost’ and the ‘strayed’, which may well be the emphatic duplication that is common in the Old Testament, but in the image, at least – by which I mean, in the reality that generates the metaphor – there truly is a difference between a lost sheep (gone right off the cliff, lost from the herd) and a strayed sheep. At the same time it should be added that there is also a difference between a visible (earthly) shepherd and an invisible and divine one, who can indeed “seek the lost”.

The strayed, the lost, have a rescuer, a saviour.

The strayed, the lost, have a rescuer, a saviour.

Ye were as sheep going astray; but are now returned unto the Shepherd and Bishop of your souls.

1 Peter 2:25 KJV

Hunt’s picture, as ‘naturalistic’ as it is, is typological in the medieval sense: a sign of Christ that echoes the truth proclaimed in the Gospel. Not all typology operates in terms of past and future (‘antitypes’ of Christ). As Biblical scholar Geoffrey Lampe notes, a second kind concerns the revelation of “eternal spiritual reality”.

[Such a] type is … a ‘mystery’ in the sense of a quasi-sacramental presentation of spiritual reality in an outward and earthly form.

G.W.H. Lampe, “The Reasonableness

of Typology,” in G.W.H. Lampe &

K.J. Woollcombe, Essays on Typology

(Napierville, Ill.: A.R. Allenson, 1957), 30

The sheep and his shepherd – word and thing, Scripture and world, eternity and history – say the same thing together. The Word spells out – though only in words – what the thing announces. This power of speaking is “the symbolism inherent in forms.”

This language of the world a modern person does not believe in and cannot read. His mind has closed to the connections.

6 | A culture without symbols

Hunt’s response to the proposal that modern people are unsuited to symbolism is at this point generally clear.

For a Christian to call the character of his or her time foreign to symbolism, as I have just done, simply raises the question of which shall prevail: the character or the Christian. To say as Rossetti did that the mentality of facts (the decay in our grasp of the nature of the world) must be honoured is really to say that modern people cannot be Christian – which would announce itself as a lie to a believer. But Rossetti could not see that

- reality is not visible reality;

- it is not words that have meaning (teaching lessons and conveying ideas); visible reality instructs; things and events speak eloquently of our situation (as works we shall examine will show);

- and – most embarrassing to a Protestant – it is the very Scriptures that tell us this, richly demonstrating that words and things are not separate realms but two modes of a single and univocal reality.

BOOK VS. BOOK

Finally, no cacophony of readings threatens us on account of Protestantism, so long as Protestantism is Christian. The trouble is that Protestantism, like Catholicism and Orthodoxy, can be used to fashion idols; “reverence for the Bible” isn’t foolproof. The Protestant who believes in the necessity of forming “individual” symbols has ceased to think like a Christian. We can call on Calvin to instruct him.

The notion that all teaching is contained in the Bible, so there is nothing for art or symbol to do but illustrate it – that is, its text, its events – demonstrates a modern obliviousness to the Bible. In his commentary on the Psalms Calvin interprets Psalm 19 (“The heavens declare …”) to say that, by that word ‘heavens’, the Psalmist

doubtless includes by synecdoche the whole fabric of the world. There is certainly nothing so obscure or contemptible, even in the smallest corners of the earth, in which some marks of the power and wisdom of God may not be seen;….

Psalm 19 then moves directly to the wisdom of the law, a wisdom revealed even in the world itself. The images Jesus and the prophets use to address the dangers and errors noted in verses 11–12 of the Psalm – strayed sheep – are just such “small corners of the earth in which the wisdom of God may be seen.” Calvin calls the created world

an open volume which all men may read; … [that] give[s] forth a loud and distinct voice, which reaches the ears of all men, and causes itself to be heard in all places. Thus we are taught, that the language of which mention has been made before is, as I may term it, a visible language, in other words, language which addresses itself to the sight; for it is to the eyes of men that the heavens speak, not to their ears;….

John Calvin, Commentary on

the Book of Psalms, trans.

James Anderson (Grand Rapids, Mi.:

Christian Classics Ethereal

Library), vol. 1

The Book of Scripture set against the Book of Nature is the Book of Scripture set against itself.

There is no age foreign to symbolism. The book of the world can always be read in the way that Christians have always read it – that is, in the way that faith elicits. The moderni really lack faith in the nature and promise of God.

THE LANGUAGE OF GOD

Cacophony of interpretation exists but in the same way that, when I am speaking French, what you are hearing is not really French. This does not prove that there is no such language.

In his reflections on the Psalms, in the chapter titled “Nature,” C.S. Lewis wrote that

Paganism in general fails to get out of nature something that the Jews got.

C.S. Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms

(1958; Boston: Mariner, 1986), 85

Pagans often misread nature, but they also could read it. Akhenaten could read the sun, sunlight, the heat given to all the nations on which it shone, by the maker of the sun.

When we read the Psalm,

I meditate on all thy works; I muse on the work of thy hands,

Psalm 143:5 KJV

we, who are infected with modernity, most certainly misconceive the verbs. We think of this ‘musing’ (it is a perfect translation, we imagine) as an open-ended mental activity spun out into the ether. We think of ‘meditating’ and picture ourselves ruminating, turning the material over and over in the mental gullet, chewing the cud but spiritually under the eye of God.

It is all wrong because what we imagine is just solitary whirring and clicking, activity. (But in the Christian tradition contemplation is spectacle, vision, seeing. Putting the question to the sunshine by hearing its answer.

.

Artist

William Holman Hunt (1827–1910)

Date

1852

Collection

Tate Gallery, London

Titled there

Our English Coasts (“Strayed Sheep”)

Medium

Oil on canvas

Dimensions

43.2 x 58.4 cm | 17 x 23 in

Photo source

Google Art Project