People in darkness | Oelze’s Erwartung

In this essay,

• A QUESTION IS ASKED ABOUT ILLUSTRATING A PSALM

• LEADING TO REFLECTION, AIDED BY C.S. LEWIS, ON HOW ABSTRACT & CONCRETE REALITY ARE REGARDED IN OUR DAY, & HOW THESE DIMENSIONS OF THE REAL ARE SEEN

• AT WHICH POINT WE LOOK AT AN ILLUSTRATION OF THE OPENING PSALM, IN A WORK SHOWING PEOPLE IN DARKNESS IN TIMES OF UPHEAVAL

• WITH A CLOSING OBSERVATION ON THE MORBID CONDITION IN WHICH PEOPLE TURN FROM THE LIGHT

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | Real conditions

Read the following verse from a Psalm but imagine that you are an artist who has been asked to illustrate it. How might you do that?

They have neither knowledge nor understanding, they walk about in darkness; all the foundations of the earth are shaken. (Psalm 82:5 ESV)

The language sets out the message but gives you little help with your task. How you might depict a lack of knowledge or understanding is certainly not suggested by the words ‘knowledge’ and ‘understanding’, which name abstract conditions.

You might, I suppose, object, saying that ‘ignorance is not abstract but concrete’, but where, then, is the concrete image? But why even make that objection: why speak as if real things have the character of materiality, as if the paradigm of reality were concreteness when it certainly is not.

ABSTRACT & CONCRETE

In the 21st century we need a certain reacquaintance with the two dimensions of abstract and concrete reality, on account of the tendency to live in one only – even despite oneself, even if we have rejected materialism. At one time these two stood side by side as higher and lower absolutes or givens of experience; this marked the field for play, but by now something has erased half the field markings.

The question I have asked (about how to illustrate something referred to in the Psalms – is it real, or “just a story”?) is in part a question about the relation between the concrete and the abstract – but we might put it in other terms: the relation between the material order and the order of meaning. Meaning is a reality.

This is a way that C.S. Lewis once used to mark this dual character of the real. In a remarkably philosophical sermon given in 1944 (yet a sermon nonetheless) he turned near the close to the late-modern habit of coming at things from the ground up: as if the one thing we could be sure of was material reality. And we should proceed, in modern fashion, with caution: with all the care of Descartes (keen, Descartes said,

to provide myself with good ground for assurance, to reject … the mud … to find the rock)

and in a secure manner frame our picture of the world.

Lewis was discussing the person who is, as it turns out, stuck in concrete reality, or rather stuck in the error he has made about how we know, and who cannot proceed further: cannot expand his knowledge of the world. He winds up leaning heavily on

Lewis was discussing the person who is, as it turns out, stuck in concrete reality, or rather stuck in the error he has made about how we know, and who cannot proceed further: cannot expand his knowledge of the world. He winds up leaning heavily on

the words ‘merely’ or ‘nothing but’. He sees all the facts but not the meaning. Quite truly, therefore, he claims to have seen all the facts. There is nothing else there; except the meaning. He is therefore, as regards the matter in hand, in the position of an animal. You will have noticed that most dogs cannot understand pointing. You point to a bit of food on the floor: the dog, instead of looking at the floor, sniffs at your finger. A finger is a finger to him, and that is all. His world is all fact and no meaning. And in a period when factual realism is dominant we shall find people deliberately inducing upon themselves this doglike mind.

C.S. Lewis, “Transposition” (1944), in The Weight of Glory

& Other Essays (New York: Macmillan, 1949), 28

But the meaning is there, there to be seen in very much the same way as matter is there – and, further, it is in seeing it, seeing it by a power of seeing that we possess, that we know it to be there: to be there as “a reality” and not a nice “story” we have told ourselves (since, for one thing, it did not at all come from us).

A WORLD OF THINGS WITH MEANINGS

When we speak with the Psalmist and say a thing like, “they have neither knowledge nor understanding”, are we not in fact talking about a ‘meaning’? Have we not experienced something that shows or means that the people we are speaking of do not understand – and that this condition is a real condition, and really the meaning of the behaviour demonstrating this ignorance?

Materiality is sensed, bluntly; you can indeed stub your toe on it. Abstraction, the realm of meaning, is intuited, registered intellectually – with an equal degree of bluntness but at the same time in wholly abstract and immaterial terms, which lose no reality for having this immaterial character.

Material and immaterial reality are different also in one other way, a highly significant way, and here we find a clumsy error in the thinking of the materialist.

[]

A thing that we see or smell (a mountain) seems to lend us help in convincing others to believe in it. But this is nonsense: the thing gives us no help, people need no convincing, we all simply see it. Yet we persist in thinking of the thing as ‘evidence’ – as if evidence were a kind of external, out-there-in-the-world, ‘proving object’. But it is not. The term ‘evidence’ (thanks to the root of the word, which refers to something being evident or visible) simply means visibility, capability of being seen. Evidence is what is already evident.

That it is snowing is evident (when snow is falling). We never turn to snow as evidence to confirm that our perception of falling snow can be trusted. That would Beg the question – assume the x (the immediate visibility of snow) that we had claimed must not be assumed but proved (by some kind of ‘reasoning from evidence’).

The error is to believe there is proof, from outside, confirming that our powers of perception are reliable. But the falling snow is simply evident; proof is beside the point, a misapplied concept. Evidence names a power in us through which the world is received. That the world is visible is a thing you experience, not a thing you test.

2 | Concrete images: darkness

But that is enough on this contemporary prejudice, this reflex default to a diminished reality: the downgrading of meaning from reality to human product. (It is a reflex that infects all current art history, in which art is a “site” of “meaning-making” in accord with the artist’s or culture’s desires. But art, art at its highest, is rather a window onto reality, a reality ordinarily hidden from us. It is that disastrous reduction, that vandalism of the mind, that this series of accounts is meant in some way to correct.)

To pick up the thread of the initial question, then, how might we illustrate this?

They have neither knowledge nor understanding, they walk about in darkness; all the foundations of the earth are shaken. (Psalm 82:5 ESV)

The Psalmist is delivering a message about invisible things, like knowledge and understanding. Indeed, aren’t “foundations of the earth” also invisible things (what is the Psalmist referring to here: surely not physical structures)?

I have said that little help is offered an artist by the many abstract terms here, but there is an image term given as well: “darkness”. How might one illustrate the reality that concerns the Psalmist?

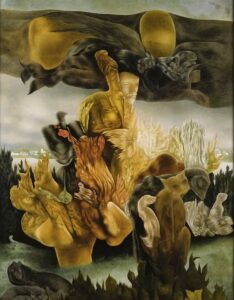

It can be illustrated in this way, a way I can show by calling up a painting that we can presume has nothing to do with the Psalms, a picture by the “forgotten German Surrealist painter” Richard Oelze.

We could right away begin looking at Oelze’s picture but there is something to be gained if we look at it equipped with one thought about its meaning, prepared for us by the foregoing.

The meaning of this image of people in darkness, and the meaning of that image in the Psalm, hangs over these images in reality.

Consider two points of substance, part of this.

[1]

First, it is perfectly clear to us that the author using this image in the Psalm is not talking about a time of physical darkness in which people are stumbling about in poor lighting. The poet has illustrated their condition with an image, and we should not be misled by this and fail to see that it is a spiritual condition.

To ‘walk in darkness’ is not primarily a natural and physical experience that we project onto the spiritual plane. It is equally and just as primarily a spiritual experience, of a sort that resonates with its analogues in the sphere of physics and matter.

That is, nature does not simply furnish material that we can use to ‘tell a nice story’, or use to depict some phenomenon in, as Lewis put it, “our spiritual life” (which the materialist will call unreal, fabricated). Rather, the experience of natural darkness – the sky going dark on us, as in Oelze’s painting, and going dark unexpectedly (the people in the painting are not gathered there looking at one more sundown) – is the deeper phenomenon heard in another key. This is what Lewis called a “Transposition” (thinking, for instance, of a symphony transcribed for solo piano).

It is aliveness to spiritual reality.

And, writes Lewis, the spiritual reality is the more profound one (“the spiritual is richer than the natural”, p. 25), yet at the same time it is manifest and conveyed in the material reality. Even its profundity is echoed there (to be in darkness is not a trifle).

What I call Transposition is [a] mode whereby a poorer medium can respond to a richer.

Lewis, “Transposition,” 24

And today’s world, hypnotized by ‘meaning-making’, won’t have this.

The sceptic’s conclusion that the so-called spiritual is really derived from the natural, that it is a mirage or projection or imaginary extension of the natural,

Lewis, “Transposition,” 25

puts everything in reverse, this skeptic forcing himself to begin in a world of matter that his own thinking can never advance him beyond. It is the abstract and spiritual thing, Lewis explained, that is grasped and conveyed in the form of a resonating metaphor.

So my first point is just this: to “walk about in darkness” is not essentially a physical or natural reality but a reality both physical and spiritual, and it is the spiritual condition that it is most crucial to understand, and the image in the Psalm and in the painting is an instrument of escape from ignorance about this spiritual condition, a way of coming to understand this state. (But we have just glanced at the reasoning by which people dismiss the very idea of an actual spiritual darkness and anything like ‘invisible foundations of the earth’, etc., so many people are perfectly inoculated against such progress in understanding. They have walled themselves into their notion of reality.)

[2]

The second point is that the reality of this condition afflicting human beings – the spiritual condition sketched in this Psalm – is ‘evident’ to people in just the way that spiritual things so commonly are. That you are a people who “have neither knowledge nor understanding” is in evidence. It is something demonstrated by the behaviour of the people, etc.

Demonstration is the appearance of some conclusion or meaning before the intellect, made present to the mind as a kind of manifest spectacle. As the eyes see the snow falling out in the yard the intellect registers the message, receives the meaning of the words or the conclusion of the argument or the implication of the facts, the message of the behaviour. And here another difference between the two powers (of sense on the one hand and intellect on the other) shows up.

If you ignore this difference you once again become trapped: a person unequipped to grasp the meaning that is before you. To fill out this second point, an aid when we turn to the image, a brief explanation.

EYES & BODY, INTELLECT & SOUL

People have ensnared and immobilized themselves with the view that the senses (which register the concrete) can be relied on because … they rest on concrete reality. But that ignores the facts, and is not true: they can be relied on because we must: we have no way to test them: the senses are a power we are given to live by.

You may test a statement (‘It is snowing’) by using your eyes, but you do not test your eyesight by using the world outside your window: the world outside your window is given to you by your eyesight, which you do not test at all.

That people agree on the basic nature of the concrete world is a tribute to the functioning power of the senses, not to some verification process, some ‘testing-against-reality’, that we imagine we have put the senses through.

The world of meaning, on the other hand, does not have this same universality: people do not see the meaning of things alike. And this inspires materialists (or whatever the best name is) to think that there is no ‘meaning of things’ in reality: the meaning is obviously coming from the people. – That conclusion does not follow. The materialist who replies ‘but what else could it be’ is very easily answered.

It is the difference that is coming from the people, some of whom see the meaning while others do not, cannot. The materialist assumption that, if meaning were there to be seen it would be seen (it would have the visibility of snow) is flatly implausible. Why should the same conditions apply in two different dimensions, home to different acts and kinds of seeing?

That people do not agree on spiritual conditions – do not agree on the meaning of the concrete world to the same extraordinary degree as they do on the realm of the senses – has everything to do with the conditions of the perception.

In addition, the facts we are usually handed are surely misrepresented, for despite that undeniable difference the meaning of things has indeed been very widely agreed on, throughout the ages. To an extraordinary degree, given the conditions affecting perception just alluded to.

That people agree on the meaning world is a tribute to the functioning power of that part of the soul that reads the world: a power that – to return finally to the assistance I am attempting to lend readers who look at Oelze’s painting – lets us move aside the veils. They are veils that also obscure the meaning hanging over the painting.

The eyes that see into this dimension come into that power through the help this power is given. Whether it sees or does not see depends upon the receptivity of that soul to the facts and forces that deliver that help. Seeing the meaning is a more complicated seeing.

That the abstract reality is poorly seen does not at all tell us that it is not there; it can be unseen and there in entirely the same way as concrete reality.

[]

As it turns out, this verse of the Psalm describes the inability to see the meaning of things that I am talking about.

The Psalmist is telling the people that “they walk about in darkness” and “have neither knowledge nor understanding” because of their failure to keep themselves in check. It is because they have not chosen to live in the way that would open them to seeing and bring them the guidance of Wisdom that they are floundering in the dark.

The two points to bear in mind, then, are these. The meaning of things is as fully there as the forest or the sky, but it is not received in the same way. The intellect, the “eyes of the soul” (Augustine), is sunk deeper in the soul where it is subject to the appetites of pride, wrath, comfort, and amusement, which are filters of the real.

Spiritual things never lose their reality owing to the state of those souls; they simply lose their evidence – their ‘evident-ness’ – and the walls raised, by us and our society, to shut the evident out can be dismantled.

3 | Fear of the unknown event

The painter Richard Oelze was born in 1900 in Magdeburg, Germany, and in the 1920s studied at the Weimar Bauhaus under Paul Klee and Otto Dix. It was in 1929, however,

when he stumbled across the work of [Max] Ernst and René Magritte in a Belgian magazine, that he found his place. ‘That’s the first time I encountered the term Surrealism. I felt an instant connection’,

Abigail Cain, “The Story behind Forgotten German Surrealist

Painter Richard Oelze,” Artsy.net (29 December 2016)

Oelze later explained. It may have been because Paris was the centre of Surrealism that he moved there in 1933, where he soon received a visit from Alfred H. Barr, Jr., director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, searching out current art to buy for his museum. Barr wrote,

I had been much interested in Surrealism since 1927 and for weeks we had been immersed in Surrealist art but we had seen nothing quite as disturbing as Oelze’s paintings.

At that visit in 1936 Expectation may even have been on the easel; Barr purchased it in 1940.

What does Oelze’s painting show us? Interpretations of this image pay great attention to its date. It was completed several years prior to the start of the Second World War, in which Oelze served in the German army (he was captured and interned in a prisoner-of-war camp until the war’s end). One writer comments on

Expectation’s ominous mood: “it is impossible not to see in the work the years of its composition, 1935–1936, and in the mute backs of its Magritte-like subjects bourgeois refugees already on their way to the death camps”.

Carolyn Burke, cited by Suzanne W. Churchill, Linda Kinnahan,

& Susan Rosenbaum, “‘I’m not the Museum’: Mina Loy,

The Julien Levy Gallery, and trans-Atlantic

Surrealism,” Mina Loy.com

That there were no death camps before 1941 and the Wannsee Conference in 1942 does not mean that nothing horrific could yet be felt. The ripples of events always spread both ways, into before and after; there are tremors. The telegram issued by the Berlin SS at 1 a.m. on November 10, 1938, announcing “Measures against Jews tonight” (now called Kristallnacht) did not come out of the blue.

Demonstrations against the Jews are to be expected in all parts of the Reich in the course of the coming night; … synagogues are to be burned down only where there is no danger of fire in neighboring buildings; … Places of business and apartments belonging to Jews may be destroyed…; … the demonstrations are not to be prevented by the Police,….

“Riots Of Kristallnacht: Heydrich’s Instructions,” Yad Vashem:

The World Holocaust Remembrance Center

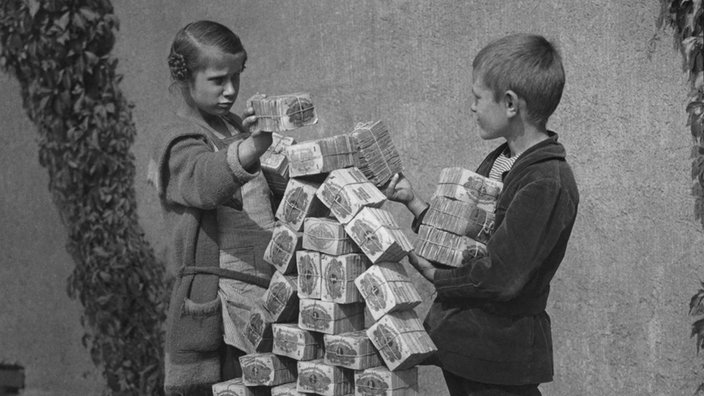

A sense that something was going to happen was surely widespread in Germany in the year that Oelze painted his picture. The country had already suffered the insane hyperinflation that is the textbook example of this evil. Fights in city streets between ideological enemies were common, as bands of nationalists went roving for bands of Communists to beat up (and vice versa).

The Twenties, on the heels of an unexpected war (a new global war) had instantly become a decade of overturning. The poet Ezra Pound had called 1922 Year One of a new era.

In his view the previous epoch – the Christian Era, he called it – had ended on 30 October 1922, the day …. when James Joyce wrote the final words of ‘Ulysses’,

Kevin Jackson, Constellation of Genius: 1922: Modernism Year One

(New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012), 3

But by the end of that year Pound had shifted to numbering the years according to Mussolini’s new “Era fascista”. To quote two other artists (Arnold Schoenberg and Wassily Kandinsky, writing to each other):

Everything has really changed since our time together…. Much that was a daring dream at that time has now become the past. We have experienced centuries. At times I am amazed that anything from the ‘old’ world is still to be seen. (Kandinsky, July 1922)

I expect you know we’ve had our trials here too: famine! It really was pretty awful! But perhaps – for we Viennese seem to be a patient lot – perhaps the worst was after all the overturning of everything one has believed in. That was probably the most grievous thing of all. (Schoenberg, July 1922)

Cited in Jackson, 190, 200

Trouble was in the air: it was invisibly already present, and that is what we see in Oelze’s canvas.

[]

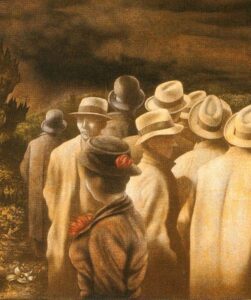

A writer who calls Expectation Oelze’s most famous work says that

it depicts a well-dressed crowd facing away from the viewer, gazing onto an empty but ominous horizon.

Cain, “The Story behind Forgotten German

Surrealist Painter Richard Oelze”

These city people standing at the edge of town stand together, turned toward a dark brown sky that takes up, literally, half the picture. As there is nothing in that sky but calmly drifting clouds it seems at first unclear what the people are looking at.

Below the knot of trees at centre right are some peculiar twisted shapes: not branches and not boards (which they both resemble and do not) but strange-looking forms that look like nothing else in this scene in which everything is identifiable. At the far right is another anomalous shape, a kind of arabesque on the grass (suggesting driftwood or shreds of fabric, but again like neither). It seems possible that the people have noticed these oddities but then it is not clear that we should read them as oddities, since they are the species of organic form that fill so many of Oelze’s pictures. They are Surrealist objects, ‘picture things’ that refuse identification – akin to the textures of fellow Paris Surrealist Max Ernst’s ‘decalcomanie’ paintings (in which odd “biomorphic textures” are created by laying a piece of glass or paper over wet paint and pulling it off).

In any case, the people do not seem to be looking at these anomalous things: aberrations they have perhaps already got used to, and count negligible compared to what is brewing in the sky.

The people are looking and wondering at what they cannot see, aware, simply, of imminent trouble. The people are brought together by this thing that has their attention, this thing they cannot see, cannot name – not that foreboding over an unknown event unites them in anything but a collective anxiety. They share a great transfixing uncertainty.

It should be noted that these people are immobilized by their watching and waiting. What they want to know and do not know about events has them standing still. The German word Erwartung (I assume this to be the title the artist attached to the painting when it was purchased in 1940) has a slightly different emphasis than the translation used in New York, Expectation, in that expectation implies a kind of knowledge, by which something is expected, but the German root is warten, to wait: you are in the dark, you do not know what to expect, you must wait to see what happens. But we could bring the two words together: the people in the painting know, they feel certain, that something is going to happen, but they do not know what.

Erwartung, I might add, is also the name of an operatic monologue written by Schoenberg that was premiered in 1924. The painting of this same title somewhat echoes Schoenberg ‘s drama in its setting: time, night; scene, a forest. A synopsis of the work runs,

A woman is in an apprehensive state as she searches for her lover. In the darkness, she comes across what she first thinks is a body, but then realises is a tree-trunk. She is frightened and becomes more anxious as she cannot find the man she is looking for.

But the drama has a denouement, while the painting decidedly does not: Erwartung. The woman finds her lover’s body, who has indeed been killed, then wonders

what she is to do with her life, as her lover is now dead. Finally, she wanders off alone into the night.

“Erwartung,” Wikipedia

But the ‘apprehension’ that was just mentioned here is a perfect term for the painting (which we might meaningfully view accompanied by a snippet of Schoenberg’s music). The people are apprehensive; there is something disturbing on the horizon – an event, things that will happen but that the people cannot see. They are standing here waiting to see, doing nothing, just waiting for the unknown thing to manifest, and waiting in apprehension. In their foreboding men and women stand together wanting to discover what is coming, all their attention captured by this slow-swirling brown blank.

Only two people in the crowd are turned away from that stage in which nothing identifiable is actually happening. We see one man in profile, a shadowed face betraying no emotion. And there is another man, but only one, who has turned completely around. But we do not know that he has broken the spell that has a hold on the others, looking fixedly into blankness; he is still there in the crowd at the edge of town. It is true that he has a perfectly relaxed expression, but for all we know he could be one of those people who is glad that the storm is coming: who has hoped for it to come because the sooner the chaos breaks and the event (whatever it is) unfolds, wreaking its havoc, the sooner the new society that he believes in can go up.

Only two people in the crowd are turned away from that stage in which nothing identifiable is actually happening. We see one man in profile, a shadowed face betraying no emotion. And there is another man, but only one, who has turned completely around. But we do not know that he has broken the spell that has a hold on the others, looking fixedly into blankness; he is still there in the crowd at the edge of town. It is true that he has a perfectly relaxed expression, but for all we know he could be one of those people who is glad that the storm is coming: who has hoped for it to come because the sooner the chaos breaks and the event (whatever it is) unfolds, wreaking its havoc, the sooner the new society that he believes in can go up.

TODAY, THE FUTURE

It is because of what the painting shows – people transfixed by events in time, by something they cannot see into, and also fear – that I recently used Oelze’s painting to capture a present-day state of mind. Once again, today, people are voicing what the painting shows: uncertainty and unease about something on the horizon, … after years of upheaval and growing tension, after unexpected peculiarities that we have registered and pushed aside as signs of a more ominous coming event. It is a concern that resonates with the facts, as I see them. (The recipe for catastrophic inflation – “a rapidly growing money supply that is not accompanied by growth in the economy” – is, for some reason, being justified again; etc.) Quotations in that article give some examples of this but here is another:

You can’t deny that it does feel like we’re [at] a bit of a crisis point right now, in history,…. I’ll be honest with you guys; I have a lot of anxiety about the future right now; I do think things are going to get worse before they get better; we’re so extremely divided right now and I don’t know how we get out of it without something historically awful happening.

Joe Scott, “Why Some Billionaires Are Actively Trying

To Destroy The World,” YouTube (18 December 2023)

Since I wrote the article yet one more person has brought up Yeats’s lines in The Second Coming, author Paul Kingsnorth writing that Yeats’s poem

reads like a news report from the 2020s:

“… Things fall apart;

the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed,

and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction,

while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.”

Paul Kingsnorth, “Our Godless Era Is Dead,”

Unherd.com (25 December 2023)

And this is why I suggest that Oelze’s painting deserves attention, and attention from those concerned with civilization. It shows us people walking in darkness.

3 | Darkness & light

People fixated on a horizon that will not answer them are people who “walk about in darkness”. People who ask, of time, what is going to unfold, are people who are lost. (They are right to think that we do not know. I too do not know. But it is wrong to devote your time to, to ‘walk in’, the darkness.)

People who put a question to darkness, to the empty sky they stare into (the stage of world events), people who hang on a question about the future, are people spellbound by darkness. That is a kind of death. From nothing no answer can come; a void can give no answer; they have turned to emptiness and are immobilized by it.

“All the foundations of the earth are shaken” when the fog that we cannot see into holds our attention, because the foundations of the earth do not lie in darkness. In one sense the foundations are unshakeable; Hannah’s prayer that “there is no rock like our God” (1 Samuel 2:2 ESV) acknowledges this; but that this rock be under us, providing its stability by foretelling all, revealing all that we need to know, requires that we step onto it and live on its support.

We have ‘shaken the foundations’ given to us by getting off them, by turning from them to stare into the future. But the future does not hold the answer.

The future does not hold the meaning of events, which is entirely accessible. Indeed, the meaning of this image is manifest to us, by the way that things are, which I have been describing.

If the order itself has spoken to us, and to us directly, why should we stand transfixed at the edge of town putting questions to nothing, waiting? Time and events are not agents. History has no ears and gives no answer to any enduring question. But Eternity and Being, on the other hand, are persons who have adopted human beings into their own dimension; they are persons who answer the questions of human beings, as a father answers the questions of his children. We are waiting for the very agent of reality (far surpassing history) to call being to its home in the promised kingdom.

Men in felt hats and women in fur collars may escape the fate of possessing “neither knowledge nor understanding” if only they begin to ask nothing of darkness. If they cease turning their backs to the light. The people in Oelze’s picture are illuminated from behind.

[]

Oelze has illustrated the Psalm – not being (I assume, as he served in the German army) a Jew attentive to the Hebrew Bible, nor, I suspect, a Christian versed in the Psalms. The Psalmist and the painter (who have nothing to do with one another apart from living as human beings in the same world) can nevertheless turn their attention to one and the same condition, a spiritual condition, a state whose meaning is exposed in the way that meaning is exposed.

To be transfixed by the causes of anxiety, to fix one’s mind on them, is to walk in darkness. To be focused on the causes of anxiety is, if I could borrow a verdict of John Ruskin (writing about feelings in a quite different context), “the sign of a morbid state of mind”.

John Ruskin, Modern Painters, ed. Cook & Wedderburn

(London, 1903-1912), vol. 5, 210

And to be so preoccupied is not only injurious but self-deceiving.

A member of this crowd who imagines that he or she is being responsible by fixating on the threat – is hunting the threat down, so as to respond correctly the moment the threat reveals itself – is a person already deceived. This person is made anxious and threatened not, as he thinks, by impending events, but because he has put himself in the hands of events. He, or she, has become a child alone before the world, and it is because of this that this person is, quite truly, in darkness and danger.

They will look to the earth, but behold, distress and darkness, the gloom of anguish. (Isaiah 8:22)

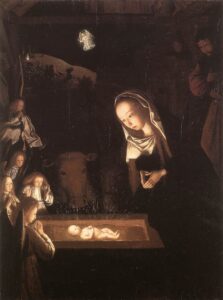

Remember that you are not in darkness because “a light has dawned.” Light itself has revealed the entire story of history:

Remember that you are not in darkness because “a light has dawned.” Light itself has revealed the entire story of history:

the people dwelling in darkness have seen a great light, and for those dwelling in the region and shadow of death, on them a light has dawned.

Isaiah, cited in Matthew 4:14–16

The promise of the light has outshone and obliterated whatever is hidden in that dark, roiling sky.

AN ILLUSTRATION, OR, REVEALER OF MEANING

Lewis wrote that

transposition occurs whenever the higher reproduces itself in the lower

Lewis, 24

– meaning that spiritual truth is manifest in material embodiments. A spiritual truth may be positive or negative; a truth concerned with darkness is also a truth about light.

The spiritual truth revealed in this image is the disaster of the fear of the future, which is in fact a submission to darkness, a voluntary departure from the light.

The actual fear of darkness that motivates the people in the painting, however, is caused not by what is hidden in the dark: by whatever crouches unseen in their century, in their future. It is caused by the “morbid state of mind” that has these people exit their homes and jobs to mill about under the obscure signs of unfolding events.

That habit is illustrated in the painting, where self-isolating people turn away from the light visible within their own lives (a light dimly disclosing time as the herald of “life everlasting”), instead to petition the void with questions: huddled together in the darkness, passive and powerless, like victims.

.

Artist

Richard Oelze (Ölze) (1900–1981)

Date

1935–36

Collection

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Titled there

Expectation

Medium

Oil on canvas

Dimensions

81.6 x 100.6 cm | 32 1/8 x 39 5/8 in.sev