Ideal government III | Ambrogio Lorenzetti on the Common Good

In this essay,

• WHAT IS BAD GOVERNMENT?

• CONCORD

• AN OBJECTION & ITS RESPONSE

• COMMON GOOD

• VIRTUES & GOODS

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | What is bad government?

Think about the good things you wish your family or your community to have. Perhaps these good things are, to an appreciable degree, missing from your city, your state, your country, even. You may be excited at the prospect of correcting that disparity of basic goods, via a change of government, as you may have had a change of government or be on the verge of one. If so, can you say what was wrong with the bad government – I mean in terms of these goods? Be specific and name the goods it failed to deliver. Or perhaps the task of that government was not to generate those goods, but instead to assist or encourage its citizens to produce them, or get out of their way, or clear away the barriers to that production, and, being a bad government, it did not. What are the goods we are talking about? What four or five can you name?

This is a probative question, a question designed to make a test. An implicit question here is, What is bad government? If bad government is in fact restricting the flow of life-supporting goods, acting in such a way as to reduce that stream (or reducing it for some portion of the populace, the stream being diverted to the favoured) then the role of the citizen is to find politicians who understand their job to be the correction of that problem. You certainly don’t want to elect a person who promises to ‘fight for you’, or a person promising to “axe the tax”, to give you merely what any person wants. We were talking the real language of politics, not in this rhetorical baby talk. Who is this person: is he a leader? Any fool knows that people would like a few more dollars in their pocket, but a leader is a person with followers, these being people whose distinctive desires the leader actually sees. The person you are ready to follow is a person who sees you to be a defender of a set of societal goods.

You should never pick a leader without, yourself, answering the question, What are the goods that, by its fidelity to them, make a government good? As I have suggested, the job of government might be just to boost the efforts of those who generate those goods, and sideline players, in the life of your republic (or whatever you are), whose actions obstruct the very goal of your state, which is to be rich in all these goods. To that end, a government might have the task of balancing these goods, so that one good (prosperity, say) would not be paid for by the loss of another.

It is only when the citizen has no such vision that politics degrades to vote-buying and meaningless ‘fighting for you’ (to do what?). All such modes of politics are deceptive, since the person giving you favours or promising the ‘fighting’ might actually be your enemy. If they are allowed to decide what goods the fight is about why should that decision, when they get around to making it, once they are in power, align with yours? The ‘goods’ they care about might well be the very commitments that are choking the supply. People should be aware that what amounts to ‘shutting the valve’ of societal goods is only ever done for the ‘good of society’.

And that means that if you cannot come up with a list, of even a few such goods, (and if you are in any way representative of your population) it will be obvious what kind of trouble your state will be in. When your leaders are left to do all the thinking you are nothing more than the lever that puts them in control, at which point they will chase whatever they call good.

[]

If you have read the first parts of this discussion on Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s fresco in the Palazzo Pubblico or town hall of Siena – considered by some to be

one of the great documents of the political ideology of a medieval citystate, part inscription and part painting, known as the cycle of Good and Bad Government”

Richard Ingersoll, cited in “Ambrogio Lorenzetti:

the First Panorama,” at the blog The Art of the Landscape

– you might have arrived at the thought, But what has this got to do with politics today?, or, OK, the old medieval abstractions (I could have guessed), but it is only now that we are coming to the moment of showdown. Who is more informed about politics: you, or the citizen of Siena who has learned what is on these walls? It might be good to find this out.

That person of Siena, an inhabitant of the town or maybe a peasant from the contado, the countryside under the town’s jurisdiction, might be no better equipped than you or I to list goods in answer to the question I asked above – but, and this is the principal point – the painting was there to teach this. That is a person who could simply walk into the town hall and, if he or she were literate, read the inscriptions on the walls – or if illiterate, could survey the images, which some guide could surely be persuaded to identify. An inscription on the east wall (it is written along the framing at the bottom of the fresco) – the final wall, which we are coming to in this last instalment – reads:

Look how many goods derive from her,

and how sweet and peaceful is that life of the city,

where is preserved this virtue who outshines any other.”

Translated by Ruggiero Stefanini in

Randolph Starn & Loren Partridge,

Arts of Power: Three Halls of State in Italy, 1300–1600

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 265

‘Indeed you may not know,’ say the town leaders (who have commissioned these paintings) to this visitor, ‘but look at these walls and learn what goods these are, so you can require them of your leaders – so you can defend the republic that fights to give these to you’. That would be something to fight for.

And you are invited to learn one more thing – quite as important, if you are in any way wondering how we have to arrange things so as to get those goods. The frescoes direct us to take note of their cause – at least, you are invited to reflect on the thing that the authors of this political manifesto believe they have identified as the cause. – And here too the 21st-century person is on the spot: do you have an answer to this question? If you have been harbouring the view that your pragmatic, modern politics is quite a bit more relevant than these medieval reflections, does your superior realism give you anything to say on this point? What is the key thing to achieve, the central thing from which those all important goods “derive”, as that inscription says?

I urged you to put your political savvy to the test by listing the goods that a good government secures. Here is your second question: in the facilitation of those goods, what is key? Is there anything you think crucially important in bringing them about? What thing, above all, must a government secure, if it is to be a good government?

Look how many goods derive from her,”

read the inscription we have just looked at. In the eyes of the author of that verse, the ‘she’ in question was Justice. Another inscription (in the frieze running beneath the frescos, and beneath the throne of “Concord”, the figure we closed with in the last instalment), reads thus:

This holy Virtue [Justice], wherever she rules,

induces to unity the many souls [of citizens],

and they, gathered together for such a purpose,

make the Common Good their Lord”

Translated by Ruggiero Stefanini in Starn & Partridge, 265

Another translation reads,

Wherever this holy virtue – Justitia – rules, she leads many souls to unity, and these, so united, make up the common weal – Ben Comun – for their lord.”

Uta Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme

of the Sala Della Pace: A New Interpretation,”

Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes

35 (1972), 146

This sums up what we have seen thus far on this wall of the Room of the Nine, and also links it to the imagery we are about to explore. To review,

This sums up what we have seen thus far on this wall of the Room of the Nine, and also links it to the imagery we are about to explore. To review,

the fresco was executed by Ambrogio Lorenzetti between 1337 and 1339. It was commissioned by the nove, the nine members of the signoria who were elected to govern the community of Siena. The image depicts the conditions necessary to achieve the ideal city state….

Hanneke van Asperen, “The Virgin and the Virtues:

Charity in Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Representation

of Good Government,” Artibus et Historiae 37:73 (2016), 57

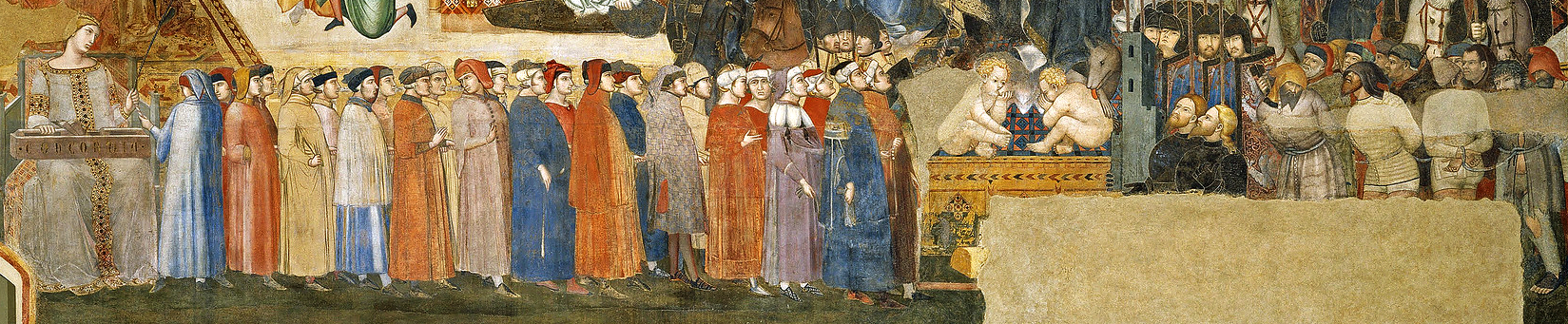

On the shorter of the painted walls, the north wall that we began to examine last time,

On the left [we see] Justice enthroned, inspired by Divine Wisdom hovering above her. The latter holds a balance, the scales of which are kept in equilibrium by Justice….The cords extending from the scales are joined in the hand of Concordia, enthroned below at the feet of Sapientia. Concordia, characterized by a heavy carpenter’s plane, passes the cord on to a group of twenty-four men, who take it obediently in dignified procession to an impressive, lordly male figure, Ben Comun, in whose right hand the cord ends.

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace,” 145

That name, “Ben Comun,” we get from the framed inscription we have just read, which also contains lines describing him.

He, in order to govern his state, chooses

never to turn his eyes

from the resplendent faces

of the Virtues who sit around him.”

Translated by Ruggiero Stefanini in Starn & Partridge, 265

To sum up, then, the whole of what we see on this wall: the state, represented by the large bearded figure that is at one and the same time the good of all the people of Siena (the common good) and the republican government of Siena (dressed in

To sum up, then, the whole of what we see on this wall: the state, represented by the large bearded figure that is at one and the same time the good of all the people of Siena (the common good) and the republican government of Siena (dressed in

the black and white colours of the Balzana, Siena’s standard,

Joseph Polzer, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s ‘War and Peace’ Murals Revisited: Contributions to the Meaning of the ‘Good Government Allegory’,”

Artibus et Historiae 23:45 (2002), 71

and seated as he is on a throne) – the whole structure of government defined in the constitution of Siena (described in the first part of this series: from the podesta to the executive council called the Nine, which served in this room) – is in fact the servant of Justice (“Wherever this holy virtue – Justitia – rules”). Who, in this political order, rules? Justice.

and seated as he is on a throne) – the whole structure of government defined in the constitution of Siena (described in the first part of this series: from the podesta to the executive council called the Nine, which served in this room) – is in fact the servant of Justice (“Wherever this holy virtue – Justitia – rules”). Who, in this political order, rules? Justice.

It is the purpose of this state, above all else, to do what is just. That means (summarizing our last instalment), discerning what is just, in both receiving and giving (in rewards and punishments, and in the distribution of goods), and in both person-to-person relations and society-to-person relations, and in all these ways rendering what is due. Where that is achieved the goods of society may flow. We shall see what, in the eyes of the Sienese, those goods are: their list is on the walls of this room.

And we have been told, in the inscription, one thing more. It is not good enough to have the plan just described: to claim to be the servant of Justice for the common good. To declare yourself such a servant, such a state, is as empty as claiming to fight for the people and put money in their pockets. That is – and I look back to the dark west wall discussed in part two of this series – talk like that is the rhetoric of the tyrant, the evil ruler, unless the governors of the state do what is just.

And we have been told, in the inscription, one thing more. It is not good enough to have the plan just described: to claim to be the servant of Justice for the common good. To declare yourself such a servant, such a state, is as empty as claiming to fight for the people and put money in their pockets. That is – and I look back to the dark west wall discussed in part two of this series – talk like that is the rhetoric of the tyrant, the evil ruler, unless the governors of the state do what is just.

You cannot do what is just, render to a man what that man is due – you cannot even identify what he is due – unless you are a person guided by “the resplendent faces of the Virtues”, and this is what we will look at now, before passing, in the last instalment, to the goods of the well governed state presented on the room’s third wall.

2 | Concord

If we pick up the discourse, so to speak, that lays out this virtual text of political theory (as Quentin Skinner characterized it in 1986), where we left it, consider the group of men at the lower level of the north wall. These figures may well be antecedents of the Nine:

The line of twenty-four figures on the north wall … are usually assumed to represent a council of that number preceding the Nine….”

Randolph Starn & Loren Partridge, Arts of Power:

Three Halls of State in Italy, 1300–1600

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 51

In 1262, when Siena wrote its constitution (which Titus Burckhardt described as

exceptional for [the way in which it] neither overlooks nor underestimates natural developments … and shows more understanding of human nature than many another such document of much later date)

Titus Burckhardt, Siena, City of the Virgin,

trans. Margaret McDonough Brown (Bloomington, Indiana:

World Wisdom, 2008), 21

the city’s leadership was to rest with the people, but (as per republicanism) the ‘people’ were not the inhabitants as a whole but identified

with a body of citizens recognized as being capable of bearing responsibility.”

Thus arose that group of three hundred councillors from the town’s three districts; also established was a

permanent magistracy [that] consisted at that time of twenty-four councillors chosen from all ranks…. Half of its members came from the knightship … and the remainder from the ‘populus’, though wealth and nobility were to be found on both sides.”

Burckhardt, Siena, City of the Virgin, 21

Woven by Concord from the cords on the scales of Justice, a rope passes through the hands of these figures before rising again to the hand of Common Good. The figure in line closest to Concord is turned as if to relay the rope; shown from the back, this figure also conceals the point of transmission and anticipates the viewer’s position in front of the picture.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 51

Starn and Partridge treat this figure as an analogue of the viewer, who might consider himself included in this crowd.

Like marionettes on their string, the figures appear to be acting on their own while acting out the message that comes from above.”

That is one of the many remarks made by these two scholars who see their task, as men of our age, to interpret what we are looking at for our day: that is, to read this painting in the corrective light of hindsight, bringing to bear on it our knowledge of “rhetoric” and “power”. We are here shown men, linked as they are to the “labeled virtues and vices” that surround them, who lack a degree of

autonomy. The figures [in the landscape] on the side walls, for example, show vital signs of a ‘life’ of their own,….”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 51

But this truly helps to remind us of how the Sienese thought differently. ‘Autonomy’ is not a value. It is obvious that, as republicans, the Sienese ranked freedom very highly; freedom was not being enslaved. But freedom was not autonomy,

Starn and Partridge mentioned puppet strings because they are devotees of autonomy, assuming their reader to be also. This just makes them correctors of the Sienese, not interpreters. Who, in this free state of Siena, according to the Sienese, should rule? If Justice were an agent, a being that could act, the answer would be Justice. That would be the dream, the ideal. But Justice is not a being; it is an ordained condition, a beloved condition (“Love justice you who are rulers on earth” – Wisdom 1:1), that is the will of God. In other words, these magistrate-citizens would be more delighted than unhappy to think of themselves as so linked to justice (and the virtues that are means to doing justice) as to be counted marionettes doing her bidding. What Starn and Partridge count a horror would be a victory, but in either case it is a fantasy, because the Sienese are the agents who have to act.

To be ruled by an ideal was a blessed condition for classical thinkers too. Wisdom was called by Cicero

‘the leader of all the virtues’, since it furnishes ‘a knowledge of things at once human and divine, including a knowledge of the relations between men and the gods, and of human society itself’ [Cicero, De officiis, 1.43.153]. Seneca later adopts essentially the same viewpoint, adding that Sapientia ought above all to act ‘as our mistress and ruler’ [Seneca, Epistulae morales, 85.22].”

Neither one would ever have thought themselves, in that very service, enslaved, deprived of self-direction.

Quentin Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher,”

Proceedings of the British Academy 72 (1986), 18

It would be a great compliment to them if they could act in such a way as to be conformed to the will of God – the divine wish for human interactions, in Siena – a dynamic that in our day is, apparently, some kind of calamity because it is responsive to something not originating in them. (The whole issue of the good being just shunted aside by this worry.) But the whole issue of ‘manipulation by Justice’ is entirely absurd, quite outside the question of whether serving what you love is manipulation. They knew very well that they could serve or not serve Justice, that it was well within their power to do one thing or the other.

It is quite stunning, in the end, that when contemplating instruction in how to escape the horrors on the west wall of this chamber, historians wind up just as horrified by what Lorenzetti presents as the solution to that trouble: conformity, in Wisdom, to a superior order.

Skinner considered the rulers of Siena the elected representatives of the citizens as a whole.

Lorenzetti’s magistrates are [shown] loosely holding the vinculum concordiae, thereby emphasising that (as Albertano of Brescia had put it) ‘concord is the virtue that, in a spontaneous way, binds together citizens and compatriots who live together in one place’.”

Quentin Skinner, citing Albertano of Brescia’s

De amore et dilectione, in “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes: Two Old Questions, Two New Answers,” Journal of

the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 62 (1999), 13

Norman points out that at its terminus that “cord is knotted” to the right wrist of the figure of the state, Siena.

Diana Norman, Siena, Florence, and Padua:

Art, Society, and Religion 1280–1400

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 148

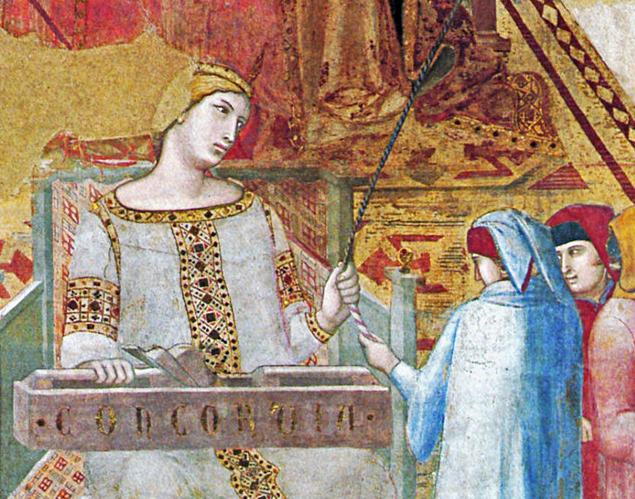

If we turn back to the enthroned figure labelled “Concordia”d, written out on the large bench plane that she holds on her lap, we ought to pay some attention to this prominent object. Frugoni writes that Lorenzetti

puts a carpenter’s plane in Concord’s hands, to symbolize the figure’s ability to smooth out all discord.”

Chiara Frugoni, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti

([New York?]: Scala Books, 1988), 3

But in carpentry long planes like this one have a more fundamental job, and one that aligns quite closely with a central issue of republican government. To use in building anything, boards must be flat and their edges straight, and in Renaissance times that job was done by planes with a long sole, exactly like the one we are shown. Skinner comes closer in his description, noting that Concordia,

balancing a large plane across her knees, … thereby indicates her willingness to overcome division and fury by making the rough places plain, smoothing out inequities and establishing the Ciceronian ideal of concordia and aequitas as the twin foundations of civic life.”

Quentin Skinner, Visions of Politics,

Volume 2: Renaissance Virtues (Cambridge

University Press, 2002), 95

It is not roughness that is the problem addressed by the plane; it is that the boards will not fit together until they are straight. A board that is sawn straight will still have high spots and low spots when it needs to be flat. It is not clear how far this analogy should be pressed, but a plane works by taking high spots down (in effect, the problem is always ‘excess wood’, in these particular areas – extended to civics, always too much power in this group and that. We have already been shown, by the figure of the balance, how central to justice is equality (the one pan of the scales must be level with the other, what is owed and what is given must be equal). The plane is another excellent image for correcting imbalance (with the additional hint that the problem is always excesses of power?). A long plane like this one (a jointing plane) is a leveller.

It is not roughness that is the problem addressed by the plane; it is that the boards will not fit together until they are straight. A board that is sawn straight will still have high spots and low spots when it needs to be flat. It is not clear how far this analogy should be pressed, but a plane works by taking high spots down (in effect, the problem is always ‘excess wood’, in these particular areas – extended to civics, always too much power in this group and that. We have already been shown, by the figure of the balance, how central to justice is equality (the one pan of the scales must be level with the other, what is owed and what is given must be equal). The plane is another excellent image for correcting imbalance (with the additional hint that the problem is always excesses of power?). A long plane like this one (a jointing plane) is a leveller.

The objective, said Skinner, was both “concordia and aequitas” . We have just discussed the latter, the concern to create equity, which is a specific kind of ‘equality’.

Kamala Harris liked to teach people about equity, pointing out that equity is not equality (everybody gets the same): some may need more than others. But the question still to be answered – critical to the very meaning of levelling, bringing everyone to the same level – is, need more in order for what? Levelling brings everyone to what condition? In the tradition of Cicero that gave us ‘aequitas’, common to ancient Greece and the Bible –

… render them their due reward”;

Psalm 28:4 ESV

… so that each one may receive what is due”

2 Corinthians 5:10 ESV

– that condition was not equal wealth or power or even privileges. People were to be brought, by the just acts of the society, to an equal enjoyment of the goods that make life a blessing. No one who participates in the generation of those goods should be robbed of the enjoyment of the “many goods” (as per the inscription on the wall) that this society is able to produce – that is, no member of this society should be deprived of his or her due portion. (The delights of the peasant in his country cottage are, naturally, not the delights of the magnate in his panelled and frescoed apartment.) This goes back at least to Plato.

In the Republic Plato singles out “the disproportionate happiness of any one class” as a basic political problem, a formula for discord (and this brings us to the other term in Skinner’s pair of “concordia and aequitas” ).

Our guardians [– roughly equivalent to Siena’s ‘magnate’ class, which furnished its armed knights] may very likely be the happiest of men; but … our aim in founding the State was not the disproportionate happiness of any one class, but the greatest happiness of the whole.”

Plato, Republic, book 4

That is the principle that, as we have seen, Siena responded to in becoming a republic. Plato’s idea of

a State which is ordered with a view to the good of the whole”

Plato, Republic, book 4

gives us, first, the very concept the common good or “Ben Comun” set at the centre of the plan of government laid out in this room. In Siena the ‘common good’ does not have the meaning it has under liberalism (which is that form of government conceived for societies that are understood to be divided in values – especially in the society’s commitment to the Church and its attendant beliefs and morals): that is, it does not have the meaning of ‘common ground’ that it has in liberalism: that set of goods that everyone accepts; ‘public’ versus ‘private’ goods. That conception of the common good – that restricted set of goods accepted as goods by everyone (the limited set that ‘public’ institutions can rightly foster without becoming ‘partisan’) – is an entirely new conception of the common good that uses the same terms employed in the ancient conception but whose actual meaning predicates the demise of the ancient conception.

AN OBJECTION & ITS RESPONSE

Right here, of course, you might conclude that your suspicion of the pointlessness of looking at medieval Siena is vindicated. You might say, Siena was not fundamentally divided, but we are, and, further, Siena could employ, to its advantage, a presumption about the good of the whole (meaning the whole gamut of good: not just safety and wealth, say, but also things like morality and beliefs about the great fundamentals, spread over the whole society) and we share no such presumptions – therefore, we can do no such thing. We must be liberals, of the above description. Even if we are conservatives, we must dedicate our ‘public’ institutions (paid for by everyone) to the common good in the new sense, the goods recognized by everyone.

Everything just said is true, up to the false conclusion, which is riddled with an egregious lie – one that Siena was too inspired by the understanding of politics you see on its walls to fall for, whereas we liberals (if we are liberals) are fools.

▪ Liberalism says that divided people can live in concord,

† and the Sienese were never open to that absurd idea.

▪ Liberalism says that in the absence of agreement about the full range of goods there can be agreement over common goods sufficient to found a free and peaceful society;

† the Sienese, however (who never would have formulated such a proposal), had they heard this, would certainly have asked what ultimate authority was urging this plan on this society and what authoritative voice would serve to secure the promised concord. (Had ‘authority’ not been dismissed?)

▪ Liberalism says that the government (acknowledging the disunity of private values) would be neutral in its public institutions.

† The Sienese would have asked what ‘neutral’ means, and in response to the answer would have said that this terminology pretends to the balance (equity) of justice, while repudiating what justice actually is (and you cannot have the one without the other). Filled in on the purpose of neutrality (its point was to ensure that public acts would not be justified with private, unshared values, and so would favour no position and be acceptable to all), a Sienese – or one who agreed with the politics advanced in the Sala dei Novi – would have said:

‘You might pretend to have a justice built on public-spirited co-operation, upon fairness-driven collegiality and not on Wisdom – Wisdom, which establishes all those essentials of being that you have driven underground as ‘private valuations’ – but you will have neither. And what is more, all your cleverness will just defraud the people.

You will not have justice because justice is the balance that is established in heaven by Wisdom, not on earth for the earthly purpose of getting-along-with-one-another.

And you will not get-along-with-one-another because you do not have justice. You will force your own in-fact ‘private’ (to use your criteria) reworking of justice upon people to whom you have promised neutrality, and in your version of equity the scales of justice will all be skewed. So, and as a matter of principle, you will manufacture injustice, and for being such a hot-house of injustice you will be riddled with discord.’

If concord and equity (obtained through justice) are “the twin foundations of civic life” (as we see in this fresco), then civic life is unobtainable for us today. How then can the political principles we count superior to those of the Sienese – merely because fundamental differences have split our societies (and there is no denying that they have) – be in any way superior? Is the direction not shown to us, by them: we must rearrange our societies so as to obtain what are always “the twin foundations of civic life”!

We have already been taught, in this room, that one of those foundations, Justice, is the source of all our goods. And we have just now seen that it, Justice, via the cords running from the balanced scales, is the source of Concord, which as a foundation of civic life is a prime good for the state to create. The absurd habit today of explaining division with reference to divisiveness (which is just people speaking out of the mouth they have, being the people they have become) makes us look simply stupid.

George Rowley remarks upon the form of this figure:

Sweetness and gentleness possess Concordia.”

George Rowley, Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Princeton, N.J.:

Princeton University Press, 1958), 100

It is interesting how this echoes that inscription on the east wall, observing

how sweet and peaceful is that life of the city”

– specifically when the city is just in its dealings: when no member of the society is deprived of what is essential to human happiness.

To compare, once again, our situation: if there is no capital-letter Understanding of what a human being needs to be fulfilled in life (‘differences in values’ mean each person comes up with his own such conception), what system of Justice would we think available to us, fit to take so diverse a set of conceptions of entitlement (and its claims of ‘not getting our due’) and reach verdicts that would restore the peace? How would ‘equitable verdicts’ even be imagined in such a society? – Inevitably, it seems, it would be someone’s concrete idea of what is crucial to happiness that would wear the officially ‘Neutral’ robes of Justice, thus installing fraud at that node of your system that is so critical to generating the two societal conditions of health, concord and fruitfulness.

If the question is, What capital-letter Understanding of what people are due would Siena have applied in its judgements, in its balancing of the scales of justice, it might be suggested by these verses from the Old Testament:

The weak you have not strengthened, the sick you have not healed, the injured you have not bound up, the strayed you have not brought back, the lost you have not sought, and with force and harshness you have ruled them. So they were scattered, because there was no shepherd, and they became food for all the wild beasts. My sheep were scattered;…”

Ezekiel 34:4–5 ESV

The issue in this passage is specified as “justice”. Notice that this is what those who ‘rule others’ owe those others, and that the one thing mentioned as a cause of this failure is an excess of pleasures and power.

I will seek the lost, and I will bring back the strayed, and I will bind up the injured, and I will strengthen the weak, and the fat and the strong I will destroy. I will feed them in justice.”

Ezekiel 34:16 ESV

The column of magistrates holds onto the cord of justice that links it with the figure seated on the throne.

3 | Common Good

The best account of this figure is given by Skinner.

Lorenzetti’s image of the signor … is … bi-valent, with two distinct representations embodied within it.… One of these is of the city itself. Many features of the enthroned figure indicate that he ‘is’ Siena. Around his shoulders are displayed the letters c.s.c.v. – Commune Senarum, Civitas Virginis.”

That is, the Commune (free city or republic) of Siena, a City dedicated to the Virgin Mary. It is notable that after the battle of Montaperti the Virgin Mary was officially designated

‘defender and governor of this city’.”

Van Asperen, “The Virgin and the Virtues,” 66

Thus it is on the shield of this seated representation of Siena that we see

an image of the Virgin Mary, chosen by the Sienese as their special patron on the eve of their victory over the Florentines at Montaperti in 1260. Perhaps most significantly of all, the regal figure is portrayed as grey-bearded, white-haired, and thus as a persona sena – as an old person, but at the same time as Sena, the Latin name for Siena.

He is dressed in black and white, then as now the heraldic colours of the Sienese commune. At his feet a she-wolf suckles a pair of twins, … a symbolic reminder of the ancient Roman republic whose insignia the Sienese had adopted in 1297….

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes:

Two Old Questions, Two New Answers,” 28

(Why Siena linked itself with Rome, to which it was directly linked by road, I do not know, but consider how this might have marked its embrace of Cicero, whose writings

(Why Siena linked itself with Rome, to which it was directly linked by road, I do not know, but consider how this might have marked its embrace of Cicero, whose writings

played a seminal role in the formation of ethical values in Western Christendom [and were a key source] the moral code of the high Middle Ages.)”

P.G. Walsh, introduction to Marcus Tullius Cicero,

On Obligations (Oxford University Press, 2001)

Skinner adds that,

while he represents the city, however, the regal figure is also the representation of a ruler, and more specifically a supreme judge…. A number of details make this reading inescapable. He is sitting enthroned on a seat of judgement. He is wearing a richly brocaded and jewel-encrusted robe of an almost imperial kind. He is holding a sceptre, the symbol of supreme authority, together with a shield to defend his people. And his legal authority is shown to extend ‘over’ everybody, including even the notoriously fractious and independent nobility. At his feet a pair of nobles, identifiable by their armour and flowing hair, offer up their castles in an evident act of homage. The verses on the simulated tablet below confirm that ‘everyone grants him taxes, tributes and lordships of lands’.”

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes:

Two Old Questions, Two New Answers,” 11

Skinner then asks a pertinent question.

Who, when these frescoes were painted, claimed to be the supreme judge of the Sienese in virtue of representing the people of Siena? … The answer is of course the Nine. In portraying the city of Siena as judge of the Sienese, Lorenzetti is at the same time offering a representation of the power held by the Nine as elected representatives of the citizens as a whole.

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes:

Two Old Questions, Two New Answers,” 28

It is made very clear, however, that the governors on this ‘seat of power’ will amount to nothing unless the power they wield is not, at one and the same time as it is political power, the powers given to them by the figures with whom they share their ‘seat’. In the Christians and classical tradition the virtues are all powers.

4 | Virtues & Goods

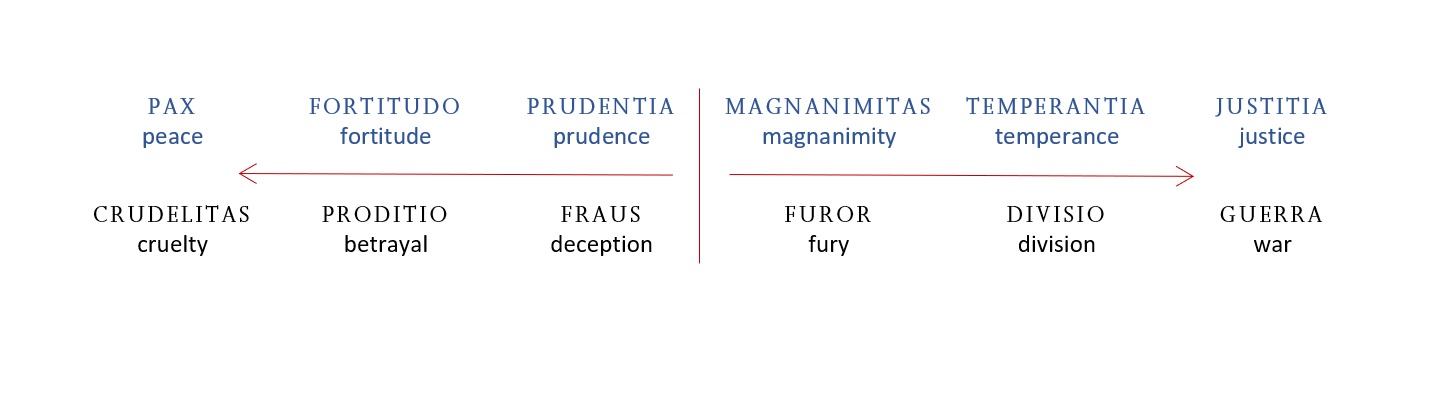

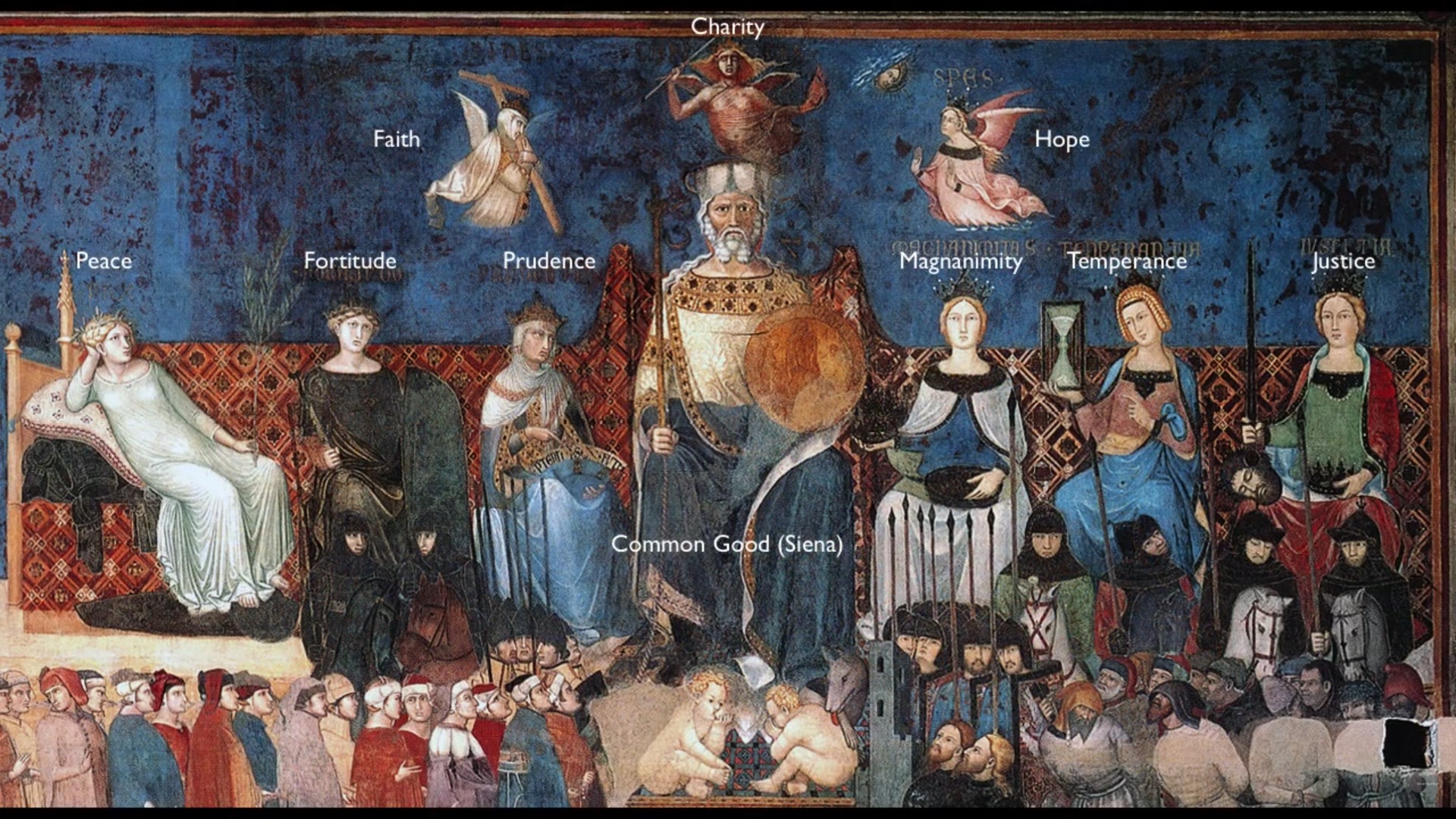

That personification of Siena, called the Common Good or

Ben Comun sits in the middle of a long bench, which takes up two-thirds of the length of the wall, flanked on each side by three virtues: Pax, Fortitudo, Prudentia on his right; Magnanimitas, Temperantia, Justitia on his left. Above his head hover the three theological virtues, Caritas, Fides and Spes.

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme

of the Sala Della Pace,” 145

Starn and Partridge note

the contrapuntal arrangement of the virtues and the vices….

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 50

We have noted earlier how the frescoes of the Room of the Nine draw upon the political treatise titled the Treasure by Ser Brunetto Latini.

Both the Treasure and the frescoes assign the highest place to the contemplative or theological virtues of Faith, Charity, and Hope, and then distinguish these from the subordinate moral virtues. Like the Treasure …, the north wall ranks the cardinal virtue of Justice beneath the intellectual virtue of Wisdom – hence the place of Sapientia at the top of the left side of the picture….

Latini gave prominent attention to Cicero’s

analysis of wisdom as ‘the mother of all good things’ and ‘the leader of all the virtues’. Furthermore, both the Treasure and the frescoes separate and balance the virtues into active and passive forms. For example, Prudence and Fortitude appear next to each other on the left side of the bench of virtues in the frescoes, while Magnanimity and Temperance are placed together on the right – precisely the relationship that is expounded in the Treasure.

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 42

To the question, how does this scheme function (in effect, is this an allegory?) Rowley, who calls these frescoes

an elaborate and complicated allegory of good government, without precedent in the Middle Ages,

also suggests that “personifications” make poor dramatic characters.

They are inadequate vehicles for conveying narrative or dramatic action. Even when the virtues and vices … are shown in combat, there is no sustained narrative interest,….”

Rowley, 100

I cannot help but agree. All the promise in the title of the Psychomachia, or battle of spirits, by the fifth-century poet Prudentius is rapidly drained away by its colossal dullness. “More complex allegory,” says Rowley,

depends for its meaning primarily on the juxtaposition of its personifications. No wonder allegory has been suspect, … and Ambrogio’s allegory has been passed by….”

But I would suggest that this is not an allegory, a drama in which the characters stand for absolutes; it is not a drama at all but a diagram. The virtues are not acting; they sit beside the Common-Good figure as assistants. Of the clearly analogous figures that flanked Tyranny on the dark west wall, Rowley notes,

the six assistants of Tyranny have been chosen with the greatest care as antitheses of the six Civic Virtues of Good Government.”

Rowley, 100

As Deception and Fury help the tyrant, so the virtues of Prudence, etc., help the ruler attain his end, which is the good of all those under him. Rowley remarks that though the artist

has tried to give life to the [image] and to make the meaning explicit … the six civic virtues, except Peace, are the usual dull allegorical personifications, with their attributes more enlightening than their forms,….”

Rowley, 100

This is quite true but it is just what we should expect from a diagram. As to how the virtues work in this scheme, Rowley makes the interesting suggestion that the seating along the bench is a kind of progression.

The meaning of these personifications has been clarified and intensified by their arrangement. Although this is not clear at a glance, consider how both the virtues and vices have been systematically bracketed in pairs. On either side of the Commune sit Prudence and Magnanimity, the initial virtues of good government from which others grow; then come the active qualities Fortitude and Temperance which protect the political system, and finally Peace and Justice which are its fruits. Analogously, Fraud and Furor are the first steps toward tyranny; Division and Treason the active agents; and War and Cruelty the dire results.”

Rowley, 105–06

This is an excellent suggestion. First, it explains why we have six ‘virtues’ beside Siena (the four traditional Cardinal virtues plus two other figures). Virtues are powers (a temperate person has the power to say no to a pleasure, like more wine). But here we have the four cardinal powers plus the “fruits” they make possible. The blue row diagrammed above is a row of goods, virtues and their fruits; the black row a row of evils, vices and the horrific conditions they ‘generate’ (acts of deception, etc., plant an evil seed).

Second, justice we have already encountered as a regulating ideal: bid to love justice by Christ (Wisdom 1:1), justice drives the political programme laid out here as its great objective, the task of the politician. (Ask a politician today what his or her task is, and what will the answer be?) In the Room of the Nine a well governed city is a city in which each person receives what each is due (Justice), according to Wisdom (an inherited and inspired understanding of life, in which our place, relative to others, is made clear). In that concord among the rulers and those who support them, the town will put at the disposal of all its citizens, according to their roles, good, well watered soil in which to flourish. But Justice appears a second time among the virtues, at the right end of the bench of the Common Good. Why two appearances?

Traditionally there were four cardinal virtues; six figures flank the personified republican rulers of Siena. It is surprising how little the art historians have to say about each of these figures. They usually just name them, but those who conceived this wall surely did not hope just that we would catch their names (which are written out for us in the fresco beside each figure). Plainly, some of what we are offered here is a diagram that does not contain but reminds of the lesson. It allows those taught the substance of these ethical concepts to recall what they had learned.

PRUDENCE

I will do my best to explain one figure more fully, but it will be much too difficult to do this for the rest, as I have had to track down the answer myself to what is now a puzzle: what was the teaching that the image we are looking at once prompted the councillors to recall? (It is a teaching very few of us have been given.)

Diana Norman writes,

On either side of the figure [of Siena], as if seated on a bench, are six female figures who can be identified by the inscriptions above their heads as personifications of the four cardinal virtues and two other virtues…. Next [to Siena] is Prudence (PRUDENTIA), who is depicted nursing a small black lamp with three flames and pointing to an abbreviated inscription which refers to the past, the present, and the future”

Norman, Siena, Florence, and Padua, 148

– fully expanded, that text would read:

PRETERITUM, PRESENS, FUTURUM”

Yves Le Guerch, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Allégorie

du Bon Gouvernement” (27 June 2019)

But according to another author, that lamp is (at the same time?) a clock:

Prudence comes next, and in her lap she holds a water clock inscribed “past, present, future”.

Shawn R. Tucker, ed., The Virtues and Vices in the Arts:

A Sourcebook (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2015), 159

The three flames (which are clearly visible) are thus the light shed by each phase of time, a light that is maintained by the figure of Prudence, who does not let the light of any wick go out. This marks a clear path to Thomas Aquinas, drawing on Cicero.

In the Summa Aquinas discusses aspects of Prudence, which is, in short,

the ‘right reason of things to be done’.”

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, trans. by

Fathers of the English Dominican Province,

2nd & rev. ed. (1920), I-II, question 57, 4

The leaders of a state must know what to do when some action is required; Prudence is the power that issues the proper answer – it is the power to obtain a certain kind of knowledge. It is a complex virtue but the image is directing our attention to only one of the aspects of prudence that Aquinas discusses. Since prudence

command[s] and appl[ies] knowledge to action,”

so that the right thing is done, and there is relevant knowledge of past, present, and future, we are seeing just that in Lorenzetti’s image. This is the lesson.

Knowledge … of the past, is called ‘memory’, if of the present … [it] is called ‘understanding’ or ‘intelligence’, [if of the future it is] namely, ‘foresight’, ‘circumspection’ and ‘caution’.”

Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II-II, question 48

If this appears obvious, that appearance is deceptive. Warren Kinghorn explains further.

First, there are two components, memory (memoria) and foresight (providentiel), which enable the prudent person to make decisions with the past and future clearly in mind. Second, there are … components that deal directly with intellectual acuity and agility: insight or intelligence (intellectus), described … as correct understanding of first principles”

Warren Kinghorn, “Presence of Mind: Thomistic Prudence

and Contemporary Mindfulness Practices,” Journal of

the Society of Christian Ethics 35:1 (2015), 89–90

that are relevant in settling what is to be done.

First principles are often called self-evident; indeed they must be, because they are truths that, logically, cannot be proved (if they could be proved then in that proof there would be premises, and those would be the first principles, while the provable truth would be established not by intellectus (perhaps our closest word is insight) but by

reasoning (ratio), the ability to navigate logically from truth to truth.

Kinghorn, “Thomistic Prudence,” 90

But because the concept of ‘truths that cannot be proved’ is scandalous to virtually every modern rationalist (of whom we have no shortage) there is endless trouble over this issue – for instance, these truths are commonly said to be undeniable. Yet medieval thinkers told us that self-evident things are deniable, because of trouble in the soul. (This, however, is not the time to say more; it is all in the book I am working on.)

It is perfectly possible, says Aquinas here in his discussion of prudence, to have an impaired intellect.

(Note then the mistake of the modern person: it is to think that the very existence of truths that cannot be proved and thus must make themselves known [self-evidence] – this, note, implies nothing about the health of human beings – means that everyone can see these truths by virtue of that fact alone; we need not even think about the issue of disease conditions that could obstruct the self-evidence. This is a plain non sequitur.)

Conditions in the soul (to which the mind belongs) can make you fail to grasp a fundamental principle or ‘first thing’, and when this is a principle relevant to knowing what to do, the decision to be made will be accomplished without the benefit this critical contribution. (For example, you might fail to understand what the human being you are about to cheat is due; your injustice has become invisible.)

Conditions in the soul (to which the mind belongs) can make you fail to grasp a fundamental principle or ‘first thing’, and when this is a principle relevant to knowing what to do, the decision to be made will be accomplished without the benefit this critical contribution. (For example, you might fail to understand what the human being you are about to cheat is due; your injustice has become invisible.)

When

Aquinas turns to various arenas in which prudence is required, he gives the examples of statesmanship, domestic management, and military command….”

Kinghorn, “Thomistic Prudence,” 90

If there is anything in statesmanship – exactly our territory – that is not deduced but is rather shown to human beings by the order of things itself, put forth to be received by the intellect, the prudent person will not resist it: that person’s soul will not have that complication that shuts out the light received by intellect. First principles govern past, present, and future.

So we have touched on the past, in memory: what must the statesman remember? (A Sienese could answer, Do not forget the God who saved us, through the dedication of our city to His mother.) Prudence also

encourage[s] close attention to present context.”

Kinghorn, “Thomistic Prudence,” 90

Following Aristotle, Aquinas said that you would not know what is due a person (the crucial question of justice) if you did not know his circumstance (suppose, said Aristotle, a person is ill: what food do you feed him?). We might say that this is all just moral deliberation, but the point made in the Room of the Nine is that imprudent people simply do not bother to look at this – they have no

circumspection (circumspectio), defined as close attention to the internal and external circumstances of a situation.”

And a last consideration of prudence concerns the future, which we have touched on in the notion of foresight. This is almost all that remains of the concept in twenty-first-century usage, and it is

caution (cautio), in order not to rush too quickly into action and therefore

frustrate our own true purpose. (Might we rush into a costly war, maybe a tariff-war, without giving proper attention to the “circumstances of a situation”, and so do all our people harm?)

Kinghorn, “Thomistic Prudence,” 90

In Lorenzetti’s image what Prudentia is pointing to is not, I think, the inscription but the central flame, the ‘burning issue of the present’. There is a decision to be made today, which she sees as an issue that is bound up with all of time. In a lamp like this three wicks are fed by a single basin of fuel. What fuels the light of the great ages, past or future, fuels the justice of today.

THE OTHER ‘VIRTUES’

Next to [Prudence] appears Fortitude (FORTITUDO) holding a sceptre and shield, and below her, as if to further emphasize the human quality that she represents, are two mounted knights.

Norman, Siena, Florence, and Padua, 148

Fortitude is the ability to persevere, when perseverance is needed. Fortitudo may be translated as Courage when there is a threat of pain or death; it is the ability to suffer, and choose suffering, when this is the only way to do what is just, what is good for all. Next is

Peace (PAX), who is distinguished by her elegant, half-reclining pose and a white, close-folded, semi-transparent robe of classical derivation. This figure is further identified by other attributes intended to allude to the state of peace: a wreath of olive leaves on her head, an olive branch in her left hand, a discarded suit of armour beneath her cushion, and a shield and helmet below her feet.

Norman, Siena, Florence, and Padua, 148

We have just seen that pain, the suffering of a siege, a war, is sometimes called for, but peace is a more perfect arrangement. Under all circumstances? If we have understood the lesson of Prudence, plainly not: it is the capacity of Prudence that assesses whether justice is done by suffering, whether the right thing to do is to have peace. But it is clear that peace within the city is a serious objective to the magistrate, because it is an essential good that all people desire, a key ingredient of the good you have sworn to give them.

(I wonder, too, if in Pax there is an element of rest, or leisure, which this relaxed figure so beautifully suggests. There is the faintest echo of the symbolic figure on the Ara Pacis Augustae or Altar of Peace of Augustus, in nearby Rome.)

(I wonder, too, if in Pax there is an element of rest, or leisure, which this relaxed figure so beautifully suggests. There is the faintest echo of the symbolic figure on the Ara Pacis Augustae or Altar of Peace of Augustus, in nearby Rome.)

Is Peace a virtue? Not in the texts on virtue. Yet is it not a power when it is achieved in a state; that is, does the peace of that state not exert a force on its citizens, drawing them to it, making them co-operate to preserve it?

[In the Room of the Nine] Peace is depicted … not simply as ‘an absence of discord’, in Thomist phrase; she is represented as a victorious force, her repose the outcome of a battle won against her darkest enemies.

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti:

The Artist as Political Philosopher,” 33

Does a city without turmoil not win people’s love? The figure of Peace, at ease on her couch, might also be an image of Siena, who attracts people to her to the extent that she becomes a true republic, a just city?

To the right of the ruler figure appears Magnanimity (MAGNANIMITAS), whose quality of generosity is signified by her attributes of a crown and, on her lap, a dish filled with coins….

Norman, Siena, Florence, and Padua, 148, 159

Its root lies in Aristotle’s praise of the great-souled man in the Nicomachean Ethics. Rowley makes it clearer that the crown and the money are being distributed:

Magnanimity, which appears in the texts as a magnifying virtue in the Aristotelian and Thomian sense, is here interpreted as a rewarding virtue for she offers a crown and dips her hand into a basin of money.

Rowley, 100

This is a virtue as fully crucial to the republic as Prudence. It is the will, within the rulers, that all the people receive the honours (crown) and material goods (coins) that are due them as fellow human beings, all the people under the jurisdiction of the governors, no matter who they are. The problem of tyranny stems above all from the opposite state of soul: my preoccupation that I receive the goods and honours that make my life good. (And there are other forms of this, disguised as care for others. It is also a tyrant who wills that the people I choose receive these goods and honours – it is my formulation of the good and not the good that is done.) Magnanimity is something much deeper than generosity; it concerns the recognition of others as those who should have what you wish for yourself. It is the Golden Rule personified as a virtue.

Next is Temperance (TEMPERANTIA), who is depicted pointing towards an hour-glass.”

Norman, Siena, Florence, and Padua, 148

Cicero calls temperance

self-control,”

Cicero, book 1, 5

which is correct but imprecise. The key is found in the Summa. In our diagram of these figures, Temperance is paired with Fortitude, in second position on the opposite side, in that both virtues are specific and parallel forms of self-control. Fortitude is the control of fear, which easily gets control over us; Temperance is the control of pleasure, which has the same sometimes disastrous power.

Temperance is about desires and pleasures in the same way as fortitude is about fear and daring. Now fortitude is about fear and daring with respect to the greatest evils whereby nature itself is dissolved; and such are dangers of death. Wherefore in like manner temperance must needs be about desires for the greatest pleasures. And since pleasure results from a natural operation, … [and] to animals [– human beings are rational animals] the most natural operations are those which preserve the nature of the individual by means of meat and drink, and the nature of the species by the union of the sexes. Hence temperance is properly about pleasures of meat and drink and sexual pleasures.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, question 141, 3

Temperance withdraws man from things which seduce the appetite from obeying reason, while fortitude incites him to endure or withstand [endangering] things [that he has good reason to endure].

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, question 141, 2

A pivotal good reason, in both cases, is that this self-control is needed to do justice. David was a tyrant for want of temperance. He perpetrated injustice against Bathsheba, her husband, their family by a lack of temperance re himself (Aquinas mentions how obsessions master us:

the sorrows that arise from the absence of … pleasures

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, question 141, 3

that lie within reach) and by a lack of magnanimity re others.

As for the hourglass, its most obvious connection with temperance is that the flow of sand is restricted to the thin stream that Lorenzetti has carefully painted that is required for the clock to function. The pointing finger of Temperance (as did the pointing finger of Prudence) indicates this one crucial thing: for the republic to function as a realm of justice, the natural impulses must here and there be restricted (and Prudence: the powers of mind must be intact and applied). (That the hourglass is a device that marks a finite and fairly brief span of time and then stops working, is, I presume, a resonant connotation of the image. The term of office of each of the Nine was two months.)

As for the hourglass, its most obvious connection with temperance is that the flow of sand is restricted to the thin stream that Lorenzetti has carefully painted that is required for the clock to function. The pointing finger of Temperance (as did the pointing finger of Prudence) indicates this one crucial thing: for the republic to function as a realm of justice, the natural impulses must here and there be restricted (and Prudence: the powers of mind must be intact and applied). (That the hourglass is a device that marks a finite and fairly brief span of time and then stops working, is, I presume, a resonant connotation of the image. The term of office of each of the Nine was two months.)

Finally, Justice (JUSTITIA) is portrayed for a second time, here shown grasping with her left hand a crown and with her right a sword, underneath the pommel of which lies a decapitated head.”

Norman, Siena, Florence, and Padua, 148

Again we have the two-handed action we saw in Magnanimity: the distribution or handing-out of two distinct things – here a recollection of what we were shown in the large Justice group at the left of this wall. The state works to reward and punish. But this is not repetition; there is something new said about justice here.

The crown in the left hand of Justice is the same crown that she wears, the crown also worn by the two virtues beside her (all six figures are crowned). What will be honoured and rewarded, in a just order, is virtue. All the magistrates and citizens that themselves have magnanimity, stop themselves from taking for themselves what is not theirs (are temperate), and in these ways are able to be just in relation to their fellow citizens will be rewarded. What is the reward? It is not of course a crown, or power; it is the reward of a just state, as on the left of Ben Comun we saw the reward of a peaceful state, a blessing won.

Those who receive from the other hand – and we see them below the seated figure of Justice, in the row of prisoners roped together and heading toward the throne of Siena now seen acting as judge – are, therefore, precisely those without magnanimity, being governed by the principle of “Each seeks only his own good”, and who do not stop themselves from taking what is not theirs, and who are unjust in dealings with their fellow citizens. Rapists, thieves, swindlers, the violent, trouble-makers: these will reap their reward.

Those who receive from the other hand – and we see them below the seated figure of Justice, in the row of prisoners roped together and heading toward the throne of Siena now seen acting as judge – are, therefore, precisely those without magnanimity, being governed by the principle of “Each seeks only his own good”, and who do not stop themselves from taking what is not theirs, and who are unjust in dealings with their fellow citizens. Rapists, thieves, swindlers, the violent, trouble-makers: these will reap their reward.

Justice is seen beheading those who deserve it and opposite the burghers is the city’s militia having captured the thieves and enemies of the state and put them in chains: one of the major construction projects of the age will be the prison added to the rear of the Palazzo Pubblico.

Richard Ingersoll, cited in “Ambrogio Lorenzetti:

the First Panorama”

In the foreground of this wall, then, we have two groups of citizens: those rewarded for their virtue, their justice (at the right hand of Ben Comun), and (at his left) those punished for their flagrant lack of it. The cord to which the good citizens freely bound themselves has, when rejected, returned as a cord that binds them against their will and drags them before a punishing judge.

Starn and Partridge comment on the general scheme of all these figures on the north wall.

Their size and position are propositional … values. The large scale and central position of the Common Good, the contrapuntal arrangement of the virtues and the vices, the predominance and several ramifications of Justice function as proofs in an argument. Formula also dictates the gender of the personifications. That the virtues are feminine follows from grammatical protocol for abstract nouns and a long iconographical tradition.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 50–51

The counterpoint referred to is the way the qualities of the figures we have just described are directly countered by those of the agents of tyranny on the west wall. I will not venture into that discussion, but will note just that there seems not to be a plan of direct pairing or mirroring by position. (For instance, Peace, to the far left of Common Good, is obviously contrasted with War, to the far right of Tyranny.) The organization of evils and vices, says Rowley, is analogously step-wise; on the west wall

Fraud and Furor are the first steps toward tyranny; Division and Treason the active agents; and War and Cruelty the dire results.”

Rowley, 106

What remains to be noted on the north wall is what, on the right side, is highest, which being highest not just governs everything below it (in what way?) but adds something to all of it that has so far been missed.

IN THE FINAL INSTALMENT:

• PRACTICAL OR IDEAL?

• THEOLOGICAL VIRTUES

• THE GOODS ‘DERIVED’ FROM JUSTICE & CONCORD

• THE WALL OF GLORY – OR, MAKING SIENA GREAT AGAIN: JOY IN THE GLORY OF THE FLOURISHING CITY

Artist

Ambrogio Lorenzetti (active 1319–1347)

Date

1337–1340

Still in its original site in the Room of the Nine (Sala dei Novi) of the Palazzo Pubblico Comunale, Siena

Medium

Fresco

Photo credit

Steven Zucker, Smarthistory