Virtue & family | David’s Oath of the Horatii

In this essay,

• FROM WHOM CAN WE LEARN? (& A THOUGHT RE THE DAILY WIRE)

• JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID’S NEOCLASSICAL SEARCH FOR A SUBJECT WITH A MORAL LESSON

• A QUESTION ABOUT HOW WORKS OF ART CULTIVATE

• AN ILLUMINATING CONTRAST BETWEEN MEN & WOMEN

• HOW WE ARE BLINDED TO WHAT IS IN FRONT OF US &, STRANGELY, CANNOT BEGIN WITH THE IMAGE

• AN IMAGE OF FAMILY, AN EMBLEM OF VIRTUE

• READING AS THE PEOPLE WE ARE

• CONCLUSION RE ALL OF THE ABOVE (INCLUDING THE DAILY WIRE)

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | What lessons, which teachers?

Has a conservative of today anything to learn from a painter and revolutionary of 18th-century France – in particular, something to learn about war, and friends? It is possible even to pose this question in terms straight from the social-media newsfeed: has The Daily Wire  (“one of America’s fastest-growing media companies … conceived … to be something unique in the right-of-center media landscape”) anything to learn from a man who would design propaganda processions (the “Feast of Reason”) for Robespierre? The entirely obvious answer to this question is, That depends on what the propagandist is teaching, but I suspect people today have great difficulty giving that answer, owing to the way that people now seem to think. That is, many appear not to believe that people are ‘liberal’ or ‘conservative’ in their thinking; they are just liberals or conservatives. The adjective is gone, swallowed by the noun: a ‘liberal’ view is the ‘view of a liberal’, so a liberal, by definition, has nothing to teach a conservative.

(“one of America’s fastest-growing media companies … conceived … to be something unique in the right-of-center media landscape”) anything to learn from a man who would design propaganda processions (the “Feast of Reason”) for Robespierre? The entirely obvious answer to this question is, That depends on what the propagandist is teaching, but I suspect people today have great difficulty giving that answer, owing to the way that people now seem to think. That is, many appear not to believe that people are ‘liberal’ or ‘conservative’ in their thinking; they are just liberals or conservatives. The adjective is gone, swallowed by the noun: a ‘liberal’ view is the ‘view of a liberal’, so a liberal, by definition, has nothing to teach a conservative.

What is this syndrome? You might think to call it ‘politicization’, but it is not. To ‘politicize’ is to zero in on the aspect of a situation that has to do with power or governance, especially the current battle of parties. There is some of that in what I am asking about but a much worse thing is accompanying it, and that is what should give us the label. Any tactical advantage we secure by politicizing is vastly overshadowed by the loss we are taking by defaulting on a duty.

THE MIRROR SYNDROME

To the extent that what is happening in the West is a clash of cultures it is more or less inevitable that the ‘conservative’ (for a conservative) is the exemplar of the human. The human being as pictured by a liberal is, of course, the ‘liberal’ (to become more human is to come around to liberal views). This is inevitable since a culture simply is the practices that some group develops as modes of human fulfilment, as that group sees it.

But you are set up for failure the moment you have fused together the unit ‘my kind/human being’, because you never came to that conception of human being by looking at yourself – but now you are tempted to do this.

The ‘human being’ that is the concern of your culture is not you or your kind; it is the human being that you have somehow encountered, out there in the world, as endowed by its Creator with admirable qualities, good and fitting qualities of its nature. Few of these were your qualities, at the start, and no matter how much you strive to exemplify humanity, certain qualities that are the glory of human beings will not be reflected in you. First, you cannot exemplify what you do not even register. Second, some of these qualities you simply cannot possess – because, say, you are a man.

So you make a fatal mistake when, having striven to be a good human being, you start looking in the mirror for what that means. You must look in the mirror, but so as to compare what you see to another model. For that you will have to look outward, to the reality that your human ideal came from; you will have to remain open to that complexity of human nature, that richness of human difference, that supply you with this developing ideal. The moment you think of ‘difference’ as coded for ‘liberal’, and turn away to the face of ‘the same’ in the mirror (frowning, of course, at whatever you frown at), you are impaired. The moment your plan of advance is liberal filters (thinking like a liberal), you are in danger of being off the track that won you any of the advancement you have achieved.

There may be a good demonstration of this in a painting from Enlightenment France.

2 | Neoclassicism & Rome: the choice of a story

It is a well known painting that comes from the height of Neoclassicism in the late 18th century. Art of that period had become remarkably diverse, but one of its directions was this.

It is a well known painting that comes from the height of Neoclassicism in the late 18th century. Art of that period had become remarkably diverse, but one of its directions was this.

From the mid eighteenth century on, a new moralizing fervor penetrated the arts, as if to castigate the sinful excesses of hedonistic style and subject that had dominated the Rococo…. It was around 1760 … that these currents gained new impetus, especially in France. There, the zealous re-examination of Greco-Roman antiquity was gradually combined with the new demand for stoical sobriety…. Diderot’s belief that the goal of the arts should be to ‘make virtue attractive, vice odious’

Robert Rosenblum, Transformations in Late Eighteenth Century

Art (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1967), 50, 51–52

gains remarkable support among artists, after the decades of the Rococo art favoured by aristocrats – with image upon image of the empty pleasures of the super-rich.

Another writer affirms

Another writer affirms

the necessity of history painting to become ‘a school of morals’ and to present ‘virtuous acts and the heroics of great men, exemplars of humanity, generosity, courage, contempt for danger and even life, out of a zeal for the honour and protection of ones Fatherland, and especially the defense of religion’…. In growing number, from the 1760s on, the ‘exemplum virtutis’ – the work of art that intended to teach a lesson in virtue – began to dominate … with particular preference given to events culled from Greek and Roman history.

Rosenblum, 55–56

It is the turn in pre-revolutionary France to the sober, civic-minded concerns of Neoclassicism.

In 1783 the painter Jacques-Louis David,  then in his mid thirties, became a full-fledged member of the French Royal Academy, the art institution of France. A decade earlier David had won the Prix de Rome, a highly coveted award sponsored by the Academy for the best work submitted, as the winners were not only inducted into the ranks of the established, they were sent on a four-year term of study to Italy, the centre of European art and classicism, where the greatest traces of Roman antiquity still stood.

then in his mid thirties, became a full-fledged member of the French Royal Academy, the art institution of France. A decade earlier David had won the Prix de Rome, a highly coveted award sponsored by the Academy for the best work submitted, as the winners were not only inducted into the ranks of the established, they were sent on a four-year term of study to Italy, the centre of European art and classicism, where the greatest traces of Roman antiquity still stood.

In the early 1780s David conceived the idea of doing another painting (it was not his first) from ancient Roman history, on the subject of the Horatii: a story, writes art historian Anita Brookner,

retold by Rollin in his Histoire ancienne, a manual read by every eighteenth-century lycéen, as, of course, was Livy.

Anita Brookner, Jacques-Louis David (New York: Harper & Row, 1980), 70

That is, the story of the Horatii was part of the vast history of Rome, from its founding to the start of the empire, written by Titus Livius (59 BC–17 AD). In Les Horaces, written in 1639, it had also been fully dramatized by the French playwright Pierre Corneille (1606-1684), creator of French classical tragedy. It told the tale of a legendary fight between the members of two families.

Very briefly, in a very early era of Roman history a boundary dispute broke out between the Romans and a rival tribe in the neighbouring town of Alba; to avoid all-out war it was decided that three young men from a family of each town would meet in mortal combat: the Horatii family would represent Rome (the ‘Horaces’ in Corneille’s title), and the Curiatii, Alba.

In fact David chose and abandoned several different moments from this story; this is worth noting as the search for a lesson worth teaching.

FIRST SUBJECT

The exact topic David at first selected was the slaying of Camilla (the subject of a fairly elaborate drawing made in 1781, now in the Albertina museum in Vienna – study 1) – or, more particularly, Horatius killing his sister Camilla, and for this we need more of the detail of Livy’s story and Corneille’s play – more of the plot but some of the drama’s actual verse. (Otherwise, why such a picture?)

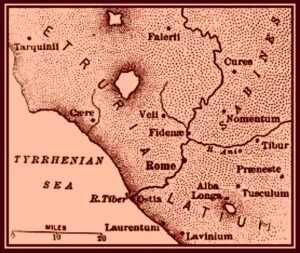

It is a story from early ancient Rome (from which virtually nothing remains), an era long before the Empire, before even the Republic, which came at the end of the Period of the Kings (753–509 BC).

Traditionally there are said to have been seven kings of Rome (there were almost certainly more), during that time when Rome was still a growing city. Rome’s third king was Tullus Hostilius (from which we get the word ‘hostile’), whose great concern was to strengthen his people into a force able to repel attacks from the neighbouring peoples of Alba Longa and Etruria, ancient home of the Etruscans.

The dispute arose over cattle raiding by the Albans along the border with Rome, which Tullus saw as an opportunity for war. War is of course sometimes ill-advised, the implicit message of what we tend to think of as ‘Just war theory’. There is, however, little that is theoretical in what is largely a checklist of the basic questions to ask in determining whether a war is prudent (is an actual means to proper human ends). One such consideration is effectiveness (is there an objective in this war, and is it attainable – or would this war be simply a futile expense of life?); another and comparable consideration was brought to the attention of Tullus by the Alban king, his ‘enemy’: the cost of victory. Could the war (even if won) trigger an injury to Rome greater than the evil it was launched to redress?

Tullus was in fact persuaded by the king that an all-out war between the towns would weaken both parties and tilt the balance of power in the favour of their mutual foe, the Etruscans, who might seize the opportunity to attack. It was better for Rome and Alba to keep themselves strong, which had thus far kept the Etruscans at bay.

Yet the issue of the dispute still had to be resolved, and Alba proposed that it could be settled by a battle not of armies but of families representative of Rome and Alba. In each of these towns there was a family of male triplets, the Horatii in Rome and the Curiatii in Alba; it was decided that these six men would fight for their entire people, the dispute to be settled in the victor’s favour.

You might, of course, wonder at this arrangement – and wonder further at both the historicity of Livy’s history and also its relevance to the age of the Enlightenment. Were there really two such families, of men so well matched in age and strength as to be accepted by their towns as worthy combatants? It seems right to suspect fiction here – and then to see that it makes no difference.

By following this story through to its end we might possibly learn something about human nature, provided the fiction is true to life and the characters represent actual human beings and do not behave improbably. These stories indeed contained lessons to be learned. It is not for nothing that 18th-century political thinkers, discussing the “science of politics” and the “causes of hostility among nations,” talked about the examples of Samnians and Spartans (see The Federalist Papers).

To pick up the thread, the question of most importance to us is, does David’s picture (the one he decides to paint) have anything to teach? It is relative to that that he is switching subjects. And this is a matter of general significance concerning what art is.

A work of art is in fact a cultural act, an act of culture or cultivation. We could say that in choosing his subject David was undertaking some sort of cultural act. But what – and what does it mean to say this?

3 | Art as culture

One thing to consider is this very purpose of art-production. We are used to thinking that art plays the role of ‘art’ and this has to do with such things as beauty, refinement, and skill; but it goes further than that, obviously. Tables and interior decoration involve beauty, refinement, and skill, and they do not do what art does – which is what?

If you are keen to move on to the picture, skip this section, but I raise here one proposal about what art actually does, as a force of culture: it interferes with bad thinking. In this it does something much more significant than deliver a message, which people often identify as its intellectual contribution.

INTERFERENCE WITH THINKING

What does a work of art do? We might say that a painting or a play may be so crafted as to shape the thinking of the person viewing it. It is highly advisable here to avoid expressions like ‘deliver a message’. Those who argue that, for the sake of civilization, art should (and does) have substance ought not to lose all interest in what they are supporting by letting themselves be palmed off with expressions like ‘deliver a message’ – slogans from the age of advertising. Civilization was not built on a base of messages. Dignify this as you may (by calling these messages sound conclusions or even truths), this so-called ‘content’ of works of art is in itself external to the soul and remains so even once the message is ‘heard’. The moment when the ‘messages have been heard’ is not the time to fold our hands, since the chaos to be replaced by civilization will, at that point, not have been touched.

As in a battle, the project is to interfere with the thing that supports the chaos. The task is not to announce something as true – to declare one combatant superior , the more powerful one, the victor – but to arrange the combat and demonstrate his supremacy. This involves the engineering of a mechanism (the work of art) that has the capacity to do that: to disturb or unsettle something making a negative contribution to society, and even overcome it.

These abstractions are not useful in themselves, but they give us something to look for in David’s work. (To that end we might form a simple hypothesis, to the effect that: in the formation of a work of art that is produced as a work of culture – a ‘reformation’ of the soul that squeezes out some quantum of chaos – something is being set up not to deliver a message but to do a kind of work. The work of art is a kind of machine that does something: specifically, puts something within us under stress. We can use David’s work as a test of this hypothesis: what subject does he choose, and to do what? )

One other thing to bear in mind is simply that the path to the final work – I mean to a work with cultural power, as just described – is circuitous, because it is not seen right away what the job of the work of art will actually be. In making his way the artist is not guided by an initial understanding of ‘what he wants to do’; he does not begin with an objective, except the objective to find an objective – or perhaps, better, a tool that has a worthy objective because of the particular work it does. (The artist can identify this by seeing what his image is doing.) But the artist finds his way under the impetus of forces that are not entirely clear. Why was David drawn to the slaying of Camilla?

4 | Choosing, continued

The answer to this question is clear from Corneille’s play, which David went to see in Paris in 1782 – but again we need the story.

In the battle only one man survives: Horatius, prominent in David’s drawing, is the last man standing. In the course of the battle, says Livy, two of the Romans were soon killed but Horatius, the remaining brother, ran up a hill and as the Curiatii reached him killed them all one by one. There is, however, one additional complexity to the scenario, which is that

the two families were related by marriage – victory for either side would bring tragedy to both.

Lorenz Eitner, An Outline of 19th-Century European Painting,

trans. Marie-Hélène Agüeros (New York: Harper and Row, 1987), vol. I, 19

In Livy’s account when Horatius returned home, victorious, he saw that his sister Camilla did not rejoice – she did not, that is, act as a Roman above all; instead she wept at the death of the son of the Curiatii to whom she had been betrothed, killed by her brother. Indeed she not only weeps but verbally attacks him, condemning his cause. Her response to Horatius, which triggers her death, is in Corneille a passionate oration – as Brookner notes,

one of the most superb and audacious speeches Corneille ever wrote.

Brookner, 72

Camilla curses her brother, saying,

Rome, l’unique objet de mon ressentiment! |

Rome, the one cause of all

my bitterness!

Rome, for whose sake you sacrificed my love!

Rome, which you worship, […]!

Rome, which I hate because she honours you….

And then she counts her personal loss just cause to call for the complete destruction of Rome – she counts Rome and all its families equal in value to her beloved. She says:

May heaven’s anger, kindled by my prayers,

Send down a rain of fire on Rome!

May I live to see this carnage with my own eyes,

See its houses burn, its laurels reduced to ash,

May the last man in Rome die aware that I alone

Brought this about – then I might die, of pleasure! |

… et mourir de plaisir!

Horatius is offended and drives his sword through her body with the words (this time from Livy),

Begone to thy spouse, with thy unseasonable love, since thou couldst forget what is due to the memory of thy deceased brothers, to him who still survives, and to thy native country: so perish every daughter of Rome that shall mourn for its enemy.

Titus Livius, The History of Rome,

trans. George Baker (London 1830), 1.26; 19

The last line here states a kind of principle. It identifies a wrong – put into maxim form: It is wrong to mourn for the death of an enemy (an opponent of your native country, fighting to steal your people’s goods) who was killed in a fight for your people’s own rightful welfare. Horatius thinks it utterly wrong, declaring the act that, in a rage, he has just committed not murder but due punishment.

Why such a subject? The death of Camilla has to do with what we might call due allegiance or even obligations of identity: who you really are, and how you ought to act because of it. Camilla’s crime is to deny her true debt and identity, setting her good above the good of Rome: to be devoted to her lover instead of to Rome and to denounce Rome on account of him.

But David abandons this subject. Is it because it is hard to see any fitting lesson in such an image?

It is noteworthy that in this first drawing the father reacts with horror (the same raised arms of astonishment that David used in a very large painting that David had just presented to the Academy and which had gained him admission as an Associate member. This is Receiving Alms, showing the Byzantine general Belisarius, who was the leading  military figure under emperor Justinian I in the 6th C AD, who loyally fought Vandals and Ostrogoths for Justinian but was stripped of his power by the emperor. According to legend Justinian had him blinded in his old age, ruining him. In the painting a soldier recognizes his former general, reduced to begging in the streets; the soldier’s raised arms are an involuntary reflex of moral shock and objection. It is the reaction due an outrage against the moral order.

military figure under emperor Justinian I in the 6th C AD, who loyally fought Vandals and Ostrogoths for Justinian but was stripped of his power by the emperor. According to legend Justinian had him blinded in his old age, ruining him. In the painting a soldier recognizes his former general, reduced to begging in the streets; the soldier’s raised arms are an involuntary reflex of moral shock and objection. It is the reaction due an outrage against the moral order.

A SECOND CHOICE

David gives up the subject and shifts to a scene of justification. The art historian Arlette Calvet writes that

the production of the play by Corneille stimulated David to start again on his project, and he executed the ‘Aged Horatius Defending his Son’

Arlette Calvet, “Unpublished Studies for The Oath of the Horatii

by Jacques-Louis David,” Master Drawings 6:1 (1968), 37

– that is, in a second drawing that is now in the Louvre (study 2).

In Livy’s account the brother is charged with Camilla’s murder but after, an appeal by his father to the people of Rome, is acquitted – as Livy himself notes, more for being the victor in the fight that has spared them a war “than for the justice of his cause.” Art historian Hugh Honour notes that, among Romans (and, I might add, their Neoclassical admirers) there was much to find fault with in Horatius.

He had displayed an admirable patriotism but a deplorable lack of the main Stoic virtue, self-control.

Hugh Honour, Neo-Classicism (Middlesex: Penguin, 1968), 35

That the story comes from the Age of Kings, which ends well before the first Stoic thinker was born, is of no significance; in the 18th century Rome was admired for her ideals of virtue, which were heavily marked by Stoic thinking.

By the end of the 1st century BC, Stoicism was without doubt the predominant philosophy among the Romans.

F.H. Sandbach, The Stoics (London: Duckworth, 1994), 16

How could David find a lesson – do any cultural lifting – in a picture of this defense, and the defense of such an act?

A complication is added by the highly notable fact that in 1783 David received a commission from the king to complete that painting: the defense of the son, after the murder, by the father – that is, David now has as a client for that particular subject no one less than Louis XVI. For the proposed work sketched in the Louvre drawing David

was awarded a royal commission by d’Angiviller [– the king’s art procurer]; the picture was to be ready for the Salon of 1783. But the project was laid aside while David completed his Academy reception piece, Andromache Mourning Hector, which was exhibited instead.

Lorenz Eitner, An Outline of 19th Century European Painting:

From David Through Cezanne (New York: Routledge, 2021)

(Charles Claude de Flahaut [1730–1809], Comte d’Angiviller, had in the 1760s been manager of the household of the future Louis XVI, with whom he developed a close relationship. Once crowned Louis named him director general of the Bâtiments du Roi, which charged him with finding art suitable for the king’s buildings – he was, in effect, a kind of minister of culture. It was d’Angiviller who judged the three works artists were required to submit for permission to exhibit at the annual Salon, the career-making exhibition mounted by the Academy.)

Yet, despite having received a commission from the king to deliver this picture David again gave this subject up.

5 | The oath of the Horatii

In fact we know how that decision came about. When

David revealed the theme that he proposed to treat during a reception given by Monsieur de Trudaine, [a] great enthusiast and protector of the arts who opened his home to a weekly gathering of distinguished artists and men of letters (among them [the author/arts administrator Sedaine),… this brilliant group showed little enthusiasm.

Calvet, 39; my translation of the lines given in French

Sedaine in particular nonplussed David by saying,

The action you have chosen is practically nil. It’s all words: a marvellous appeal, lending itself to fine gestures of oratory of just that sort that attracted Corneille…. But further, would our French manners take kindly to the fierce authority of a father pushing his Stoicism so far as to excuse his son for the murder of his own daughter? … We are hardly ready for a subject like that!

Calvet, 39; my translation

Apparently David departed to think the matter over, then

returned to the gathering and announced a change of subject: ‘the moment which must have preceded the battle, when the elder Horatius, gathering his sons together in their family home, makes them swear to conquer or die!’ [study 3]

Brookner, 75

THE FINAL CHOICE OF SUBJECT

This is the work that David indeed painted, and of interest to us. It is worth underlining that in making this choice David was not thinking about satisfying his patron, none other than the king; rather, he was thinking about the public reception the painting would be given when it was exhibited at the Salon, as it eventually would be. What work the painting would do very much mattered to him.

In reflecting further on the subject of the Horatii, David realized that the episode he had chosen and for which he had received a commission was unsuitable. He now decided to represent a scene of his own invention, for which there was no authority in Corneille’s play or in history. He imagined the father arming his sons for the battle and pledging them to self-sacrifice, while the women of the family mourn the foreseeable deaths of brothers and husbands.

Eitner, vol. I

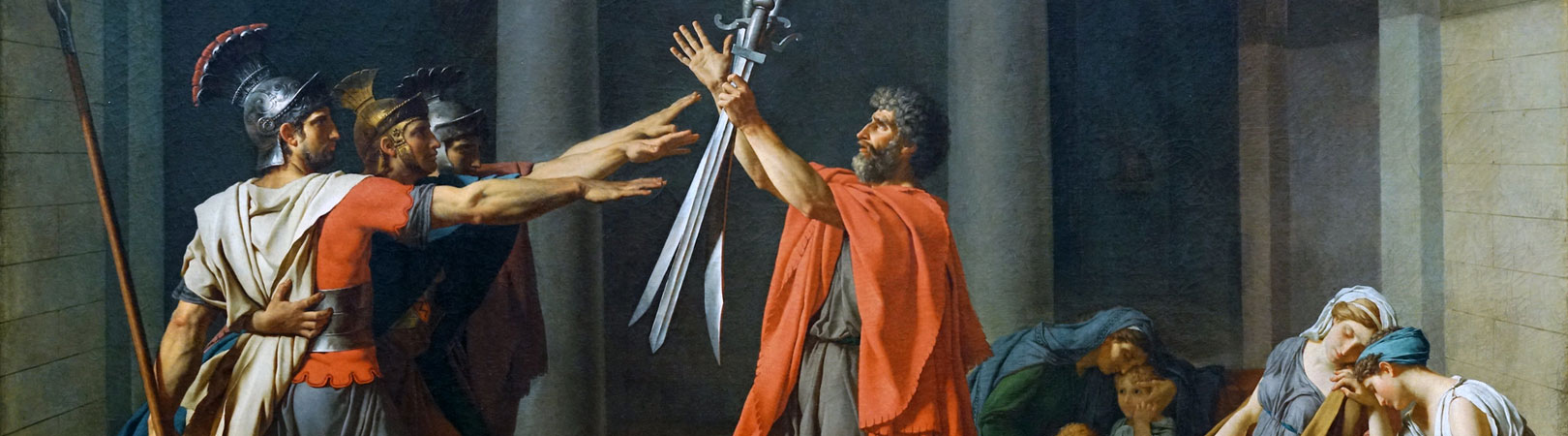

As Lorenz Eitner notes, “The composition is of Spartan simplicity.” The figures are sharply lit from one side; they are simply arranged, set in a kind of quasi-classical frieze parallel to the picture plane. The figures are sculpturally distinct; their gestures are clear. The background is simplified; there is nothing there (no distances, no windows to look through) to distract from the action. The architectural arcade is plain; note the columns: Doric, the simplest, no fluting, no bases. The Roman arches divide the scene into three equal parts.

In the two thirds at the left you have the three Horatii, “tensely erect,” bound together “by a single, taught” outline, and united in an embrace. Then comes the father giving his blessing as he hands his sons their swords. This, the subject that David had announced at the gathering, is indeed the focal point of the painting, even in an ingenious and subliminal way (the perspectival lines of pavement and stone courses converge on the father’s hand, clutching the swords). But the painting has another third; in the final bay are seated the rest of the family. David has painted the entire family, the sacred and most fundamental unit of Roman society.

To the right are the women: the mother of the sons sits in shadow with in the foreground Sabina (a sister of the Curiatii brothers who is married to one of the Horatii, with her children at her knee) and in the corner Camilla, betrothed to a son of the Albans.

The women swoon in helpless grief, their limp bodies and flowing garments in perfect contrast to the hard metal and muscle of the men.

Eitner, vol. I

THE DUALITY

You have in the final painting a duality that is in some way about gender, a duality so prominent that it cannot be ignored. And it is at this point that we pick up the thread of art and culture, or art as an instrument of cultivation, formation. If there is anything formative about the work David created (the subject he finally chose and what he chose to make of it) it will have to do with the character of the work and what it emphasizes, the things that his image in fact presents.

It is reasonable to say that chief among these is that duality, the contrast between the two groups, for which everything else in the image serves as a stage. (If you look back to David’s first drawing you have a scene of considerable complexity: who are the many figures ‘on stage’, what are they doing, what is their attitude or relation to the central event? In the painting all such questions are swept away; what was once complex, writes Brookner, has been “reorganized into an emblem of iconic simplicity” – 69.) Here is how two scholars, commenting together, describe the contrast between the men and the women.

Look at how David has depicted that contrast…. The male figures are rigid, … upright, … tall, strong. They are angular in the forms of their bodies. They raise their arms together. There’s a sense of purpose…. The young men are working in unison. Their arms salute in unison. There is clearly a reverence for the idea of strength in a brotherhood, in a collective.

That taughtness in the posture of the men (one posture for all) is a function of their resolve; the sons are a machine primed by the father for action. You see the opposite in the women: collapse and thus dysfunction:

the women are curvilinear, … their bodies are limp;

the purpose we see in the men

is completely absent from the women, who appear to be just victims of circumstance here.

Beth Harris and Steven Zucker, “David, Oath of the Horatii,” Smarthistory

The closing words of that last line, however, take a step beyond registering what is visible – what is undeniable in the action, the bodily attitudes, of his figures – to reading and interpreting these attitudes, understanding what they mean.

We have, it is true, read the stance of the men as resolve, but that this is a painting with resolve as its theme is loudly signalled by the act of oath-taking that we are plainly seeing, reinforced by a title likely chosen by David. (Titles accompany works submitted for exhibition at the Salon, publication in text-only exhibition catalogues printed for the convenience of buyers, enthusiasts, and, arising alongside these exhibitions, also art critics.) Though there is no scene of oath-taking (or ceremonial arming) in any of the narratives I have mentioned it is clear that after the decision arrived at by the two kings was brought to the family of the elder Horatius, implicitly, a question hung over the plan, concerning the response of the family. Tullus would hope that he could count on the Horatii – though we might wonder whether an ancient king would leave them any choice in the matter. But that last question David has surely answered: the sons pledge themselves to Rome willingly and with fervour, ready to die in the place of their people.

In fact, given what has long been known about Roman society, it is the paterfamilias who would have made this decision, pledging the sons himself, and they, if good and faithful men, would heed the will of their master, their father, who in Roman times

exercised legal power of life and death over his entire household, including his spouse, children, relatives, servants, and slaves.

Roy T. Matthews & F. DeWitt Platt, The Western Humanities, 6th ed. (Boston: McGraw-Hill,

2008), 120

This is surely what Brookner meant in calling this, quite rightly, a picture in which

the brothers swear an oath of allegiance to their father.

Brookner, 70

They accept the duty of a decent Roman: accept what is owed to both father and fatherland – to their fellow Romans. In David’s painting the men show what answer they give to the call or the command put to them; they might, after all, have been different men (might have made the choice we can so easily imagine making) and fled from Rome.

My chief point in the preceding lines has simply been to note that seeing resolve in the men is virtually inevitable; you could not see anything else. This is straightforward reading; there is nothing to understand, nothing ambiguous or hidden that requires you to interpret. But that is not the case with the women.

THE PICTURE AS A WHOLE

Before we see that, it may be useful to propose for David’s painting a somewhat altered title. At least, we ought to correct the tendency (surely a mistake) to see the ‘Oath of the Horatii’ as what is happening in the left part of the painting; it is not. The subject of this picture, named in the painting’s title, is happening on the right, too; that is, we would better understand what we have here if we read the title as The oath of the Horatii in the family of Horatius. This is not a painting about young men, with background women; it is a painting about the central unit of Roman culture, the family, and that family in relation to its society (which is implicitly present here, as without Rome and its welfare there would be nothing to decide). And this means that the painting could be understood as (but this is too dryly analytic to be a title) The response of the family of Horatius to a grave civic duty. Now we are in a position to read the picture as a whole.

6 | Academics reading art

THE WOMEN

If it is clear what position the men have taken in response to this call to defend the interests of Rome (and spare it the disaster of war), the position of the women must be understood, and to see that there are different ways to understand the way David presents them we can turn to art historians writing about this painting. Here is one assessment of the women’s position (of the male-female duality that is present here).

[In David’s picture] masculine will is pitted against feminine sentiment; civic dedication hardens the men, natural feeling overwhelms the women.

Eitner, vol. I, 20

And here is a second.

David’s paintings everywhere show a strange conflict between the genders: he divides humanity not just into the two sexes, but into two distinct species, where the males are concerned only with political action, heroism, and self-sacrifice, and where the female loyalties invert the male ones – family before state, the rights of children before the rights of the polis, peace before war.

Norman Bryson, Word and Image: French Painting

of the Ancien Régime (1981), 147

Are these comments accurate characterizations? In the first, “pitted against” suggests something more than contrast; it has the meaning of direct opposition. The contrast between the men and the women, I have said, is undeniable, but do we have here actual opposition? Two other art historians writing about The Oath take that position.

By making the women appear so curvilinear, so passive – they don’t even have their eyes open – David is suggesting an idea that was very prevalent in the philosophy of Rousseau, for example, that women could not be true citizens of the state. They were unable to think about civic responsibility. Women could only think about the personal and the familial.

Harris & Zucker, “David, Oath of the Horatii”

David, according to these writers, demonstrates the prejudice of his time (holding a view of women articulated by Rousseau) by showing the women in the grip of their nature. He has presented them as “unable to think about civic responsibility”: as not capable of weighing the issues and seeing, as the men can, what ought to be done. Prudential decisions (decisions about what to do) involve weighing all the issues, and as women feel the weight only of personal loss they are unable to see and apply the countervailing weights – they cannot ‘use the scales of prudence’, so to speak. (The remark that the eyes of all three women are shut appears to suggest just that sort of incapacitation.) But if we are seeing women who “could only think about the personal and the familial” then, of course, we are seeing people capable of decision: a decision made under the sway of their impaired nature, a decision against the loss of husbands, brothers, and fathers, against the resolution to fight. (Wouldn’t the fact that the action of the men takes so much space in the painting mark the men’s deliberation as good, the women’s as bad?) Accordingly, these are women taking a position opposed to that of the men – or, to pick up Eitner’s expression, these are women “pitted against” the men.

The second quotation demonstrates a very similar position: this male-female opposition of nature and judgements can also be expressed as an opposition of loyalties.

The female loyalties invert the male ones – family before state, the rights of children before the rights of the polis, peace before war.

Bryson, 147

That this is all a coherent interpretation of what we are seeing is obvious, but is it an accurate reading of what David has presented?

A PREJUDICIAL PRESUMPTION OF PREJUDICE

It is noteworthy that to read the painting in these ways you must begin with a thing that you cannot see in the painting; you must begin with the act of crediting David with blindness. The impetus to do that will of course be present if you align your scholarship with a progressive view of history (the past is the home of prejudice, etc.). But suppose we begin with what we are seeing, with the image, and no specific consciousness of Western thought at all.

Where in the picture do we see any actual opposition; does the difference between the men and the women imply it? It is not strictly possible to say what judgement the women have reached about the resolve of the men, yet we do see their response to it: suffering. In Corneille’s drama Camilla’s judgement and opposition are expressed unambiguously by her words. In David’s picture Camilla is thought to be the young woman in the corner, since she is as yet unmarried and the children in the painting are likely gathered near their mother; in David’s picture, however, we have no sign that Camilla opposes the decision of the men (in so doing rebelling against her father). We cannot even conclude that inwardly she is “pitted against” the men’s decision and turns away to hide her feelings; she is not hiding her feelings.

How do those who count the women’s misery a sign of their disagreement imagine the women would appear if they agreed with the men? Are we to imagine them sitting upright and content, or rising to their feet to cheer the heroes on? There is something very wrong with – something inhumane in – the implication that the women, in agreement with the men, would be behaving very differently from what we are seeing. (The connection with the conflict at the Daily Wire, which parted company with a woman in that ‘family’ on account of empathy she had shown over victims of war, arises here, but I will say more on this only in the conclusion.)

In Corneille there is an explicit contest between reason and passion, where passion (a key concept of ancient morals) is not just succumbing to feeling but falling under its sway, acting under its direction. Corneille’s Camilla does so when she condemns her brother and Rome, but David’s Camilla neither speaks nor acts; she simply suffers.

WORDS

On the issue of words it is fitting to cite another art historian who registers what was earlier called passivity (Harris and Zucker) and explains its significance. The Oath of the Horatii shows us

an all-male society, marked by intense ties among its members, from which women are excluded…. In the Corneille play … Camilla … is permitted an impressive verbal denunciation of Roman militarism. By contrast, ‘David’s women are silent and have neither word nor image to challenge men’.

In that last line above this scholar cites Norman Bryson, who had written,

‘The Oath’ is an exact image … for the subject living under patriarchy. The females, denied political authority by the patriarchal mandate, are consigned to silence, to the interior, to reproduction; while simultaneously the males are inserted into the … registers of language and of power convergent in the oath….

Bryson, 70-74

I accept Bryson’s suggestion that the men here are speaking. In the image, of course, no one says a word, but that is just because David has so thoroughly taken his friend Sedaine’s advice to paint deeds and not words, yet the ‘oath’ of the title is fundamentally an act of speech. David has simply found a way to depict it through action, a thing that a painter can paint.

If the men speak and the women are silent the viewer of the image is indeed tasked with making sense of this difference, and I now come back to that earlier question of preliminaries: of decisions that a reader must make in his or her approach to reading ‘what is there’. That is, you cannot always begin with what is there.

The first three scholars just canvassed (Harris, Zucker, and Bryson), sensitized as they are to the low regard for women in Western history, began by counting David an exponent of that prejudice. The same approach lies open to you in understanding the women’s silence: David’s women simply act out the role handed them by patriarchy (which David finds normal and proper): it is because the women have internalized the message that their emotion-driven opinions do not ‘deserve’ a hearing that, ‘appropriately’, they close up in silence. In approaching this painting the interpreter must in fact answer a question: what role are these women enacting? Are they conformed to a false role (dictated by dismissive men) or are they acting, here, as free beings, playing the role that they themselves choose, because it is representative of who they in fact are?

You have only to pose this question to see how unreal it becomes in the eyes of a person persuaded by the critique of patriarchy (the father-led society as a structure of women’s oppression): that there are two ways of reading what is in front of him never enters his mind. (Yet there are two ways.) It is not that he cannot conceive of two roles the women could play (of course he can), it is that his conception of women acting in such a way as to truly fulfil themselves (whatever that way of acting would be) would not fit what he is seeing in this picture. No liberal thinker looking at David’s picture is at all faced with the question, which of those two roles are we looking at?

But having come this far we are now at the point of seeing that that is because interpreters have to interpret as the people they are, and liberal-minded interpreters are blinded to the fact that this question is a real one. All of the scholars I have read are driven, by their outlook, to interpret this painting as expressive of

a polarity between masculine strength and feminine weakness,

an actual “schism” visible in many works of this era but that in the Oath of the Horatii is shown to

rupture decisively the unity of the family.

Art historian Robert Rosemblum sees this emphasized in

the composition … but even [in] the drawing style[, which] distinguishes between virile self-determination and feminine abandonment to weaker passions.

Rosenblum, 70–71

But it is entirely possible to see what is going on in this picture as almost the opposite of this characterization: not any “decisive rupture in the unity of the family” but just the contrary – the unified family, operating as a fully human and indeed exemplary unit of society.

7 | People reading art

Scholars read art as the people they are. It is people who interpret, and they must do so under the guidance of what they in fact believe. The idea that in the 20th century we at last came to possess the discipline art history as ‘historical science applied to art’ – as we saw this expressed in the last essay,

a natural science of the spirit

Irving Lavin, “The Art of Art History: A Professional Allegory,”

Leonardo 29:1 (1996), 30

– in which scholarship is freed from partisanship and the interpretations advanced by scholars are suited to every user, whatever his or her beliefs – is a false idea (given to us as a function of the liberal reordering of society). What a person believes always directs the way he or she reads – and also limits it (this being good or bad depending on what the limit keeps them from) – and there are beliefs that make it impossible to see what is in front of us. We are looking at such a case in these academics’ treatment of David’s Oath.

The emphatic contrast in this picture between the men and the women is a contrast of function, not opposition; it betokens a division of concern that, fully in accord with reason, ensures that everything deserving recognition is justly recognized. The women let themselves inhabit their suffering, rationally, because of the natural affection they extend by nature to the members of the family for whom they care, their accepted role. People must be cared for, and men too possess this capacity of familial love – but this is not their work, and there are times when the work that is theirs, outwardly directed at the surrounding society, would be impeded by it. Mourning is a human duty, the anticipated loss must be acknowledged, and it falls here to the women.

Could we not have here that exemplum virtutis that Neoclassicists sought? If this were an image of a family ‘inspiring to virtue’ because this family exemplifies virtue, the women will grasp the agonizing rightness of the men’s decision. At this moment of resolution, the women are silent about that decision because there is no cause to plead; as the men can love the family so can the women fathom the sacrifice and see its true supremacy. But nothing requires them to stifle their humanity and suppress their feeling. That the men must steel themselves by giving all their attention to the good of the battle does not mean the women should mimic them. (It is weak men who look to the women and are annoyed that they are acting differently, not acting like them. It is a weak man who needs the women to be men.)

It is essential that horror not be downplayed, even in support of a righteous task. This is why David abandoned the two subjects he had earlier considered. It is a part of decency to express the horror that is due the outrage against life that is killing. Even when the killing is self-sacrifice – and so not an outrage against the moral order but a fulfilment of it – there remains something deeply wrong in a world that calls for this, and this must be acknowledged. A human being must, to be a good human being, express the horror that is the right response to the world’s darkness; we are seeing that motif here for the third time in David’s work. It is possible, so as not to subtract from the work of the warrior, to order society in such a way that this duty falls to another group. But to suppress the expression of grief would be yet another moral outrage.

David’s picture is an image of a Roman family (the cell of the polis or state) that is fully attuned to the harsh realities of social life, a family that is an exemplum virtutis: a whole whose members take up together (with no inner friction) all that must be done, in the roles that family and virtue allot them – roles that they choose.

MISUNDERSTANDING THE PASSIONS

Because feeling is visibly central to this work, a pivot of the contrast (two kinds of feeling are presented here), the confusion caused by misunderstanding the ancient theme of the passions needs dispelling.

The women as David has depicted them have been called “passive”: “feminine abandonment to the passions” (Rosenblum, 77) and also giving in helplessly to the will of the men. But in the ancient world passive was contrasted with active, and action is something chosen. (‘Reaction’ is, I think, not an ancient word, but it is a fair term for things we do that are not chosen.) It is right to look at the women and speak of ‘passion’ here, but not if this sees them as powerless to act.

Feeling indeed comes over the women, and this is indeed the central idea of ‘passion’ (we are called ‘patients’ in the hospital because of an illness that befalls us, not of our choosing, and of a treatment we receive). But it does not overpower their minds; it overwhelms their bodies. (David’s “curvilinear” treatment of the women is employed in rendering their bodies.) ‘Abandonment to the passions’, however, means that the feeling overwhelms the mind: people are driven by what they feel, not what they decide – indeed, if women are given to passion they cannot think and decide, they are (à la Rousseau) ‘prudentially impaired’. But in the Oath the closed eyes of the women signal no such thing; in shutting their eyes they are simply shielding themselves from what they cannot bear to see. The women are not giving in to the passions if we are seeing here an exemplum virtutis, and nothing here suggests that that is not so.

Feeling is widely misunderstood today precisely because the ancient ethics (the thinking of Aristotle and Cicero that ‘Neoclassicism’ was working to popularize) has largely been lost. Feeling is neither virtue nor vice but nature, said Aristotle. Vice and virtue attach to acts, which must be rightly chosen, often under the onslaught of feeling, which must be fought. There is no conflict whatsoever between ‘passion’ in the simple sense (feeling that befalls you) and reason; reason tells you what to do precisely in the circumstance of a deluge of feeling. The ‘passions’, however (you see that this is actually a different term), which were condemned by the ancients (Greeks, Romans, and Church Fathers), were actions dictated by feeling – with reason shut out of the process, or overridden (‘reactions’). The thing that we should do is not settled by feeling alone – which is to say, by the goods that all feeling rightly honours. (The supposition that liberals care about feelings and conservatives about reasons misses the fact that feelings acknowledge goods that provide reasons. Facts may not care about your feelings, but reasons do: they take them into account.) All the goods must be weighed together.

To get now to the point, the women in the picture give in to feeling because doing so is right; this is their own judgement. They do not will themselves to feel, but will the open display of their feeling: they do not shut away, for anyone’s sake, the sympathetic death that their postures publicly announce. Equipped now with the ancient understanding, you will see that that is not succumbing to the passions; it is rational action (prudence, virtue). At the very moment of the oath the women see that it is already time to grieve; loss of life, now guaranteed, must be mourned.

There is no reason not to believe that the women in David’s image are directed in a fully human way by their own will, having understood the action that is due; we have no reason to think that, being just conditioned victims of patriarchy, they do not exemplify virtue. David shows us women expressing their grief, not making any abstract point that feelings ought always to rule. As for the words “female loyalties,” could you conclude, looking at these women, that they hold the view that family must be protected at all costs, that family comes before state, that the bonds of family should trump the bonds of polis? This would be putting words into their closed mouths and speaking over what they are actually showing, which is that there is a place in life for both sacrifice and feeling. In fact they are natural to the roles of warrior and care-giver caring for those in the home. David has depicted the cost of both these differentiated roles.

virtue. David shows us women expressing their grief, not making any abstract point that feelings ought always to rule. As for the words “female loyalties,” could you conclude, looking at these women, that they hold the view that family must be protected at all costs, that family comes before state, that the bonds of family should trump the bonds of polis? This would be putting words into their closed mouths and speaking over what they are actually showing, which is that there is a place in life for both sacrifice and feeling. In fact they are natural to the roles of warrior and care-giver caring for those in the home. David has depicted the cost of both these differentiated roles.

8 | The meaning of the contrast in The Oath

Is the meaning in David’s contrast of the sexes not finally apparent? It is division, not as “rupture” but as differentiation. As the division of the sexes is purposive and constructive, so too is the division of the sexes in David’s image of a good Roman family.

The family cleavage … so prominent in the Horatii

Rosenblum, 77

is not present in the Horatii, which shows us the whole intact, bearing by its differentiated parts all the burdens of virtue. The 18th-century person (including the soon-to-be Revolutionary David) indeed knew that there was an ancient tradition (of which the Bible is part) in which men and women are seen as innately specialized, starting with their bodies. (We have encountered this earlier in this series in Veronese’s Venus and Mars.)

There is also a whole that the differentiated parts create: the union of woman and man mentioned in Genesis, a self-replicating whole (signalled in this painting by the inclusion of children): the family. Just as an eye is different from an ear, yet both are parts of a whole, so the father and the sons, the mother, daughters, and children all play their allotted roles. The mother of the family shields the eyes of her grandson so that he does not see the glamour of arms (he is too young to understand more). She knows that the allure of war can launch evil wars, incurring senseless loss, but she does not resist the boy’s effort to pull her fingers apart so he can see. The boy, even now, is drawn to the role that he must one day assume; even here and now, in the way of a child, he is playing the role of just defender.

The dominant note of David’s picture, the resonant chord sounded by the gesture placed at the very centre of the image, is positive and heroic, and that that is the tone that David has given to his picture suggests that the oath is the response to a calling, commitment to a higher good. (If war is not always warranted neither is self-sacrifice, but we do not have in this image anything to justify that line of reflection; it would be a remark irrelevant to this painting’s statement.) But in so much of life the major chord is shadowed by a minor. There is a kind of duality in the moral order itself (played out here on earth). Indeed, it is the combination of both chords – rather the whole page of music – that is surpassing and sublime. (“Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” – John 15:13.) The painting does not sound only a major chord.

The heroism of the brothers will cause loss of life, which is a great loss, and it is essential that it be noticed and lamented. But the father committing his sons and the sons perhaps going to their deaths (two here will die) cannot think about this; having declared that they are ready to die, for others (and thus avert a war, with this same loss multiplied many times over in the families of two towns), they cannot turn their thoughts to sadness. The women can and must, and in doing so participate in this act of the family, chosen for the society. There is no ‘decisive rupture of the unity of the family’. In the Oath of the Horatii we are seeing a united family at the precise moment when all these actions are set in motion.

Some will die, some will grieve. There is no contrast here between reason and passion. The women are not helpless and ineffective but as human beings choose the role that falls to them in a familial act of virtue. The family in this image is comprehensively rational; every due consideration has a bearer; each different person’s nature does its own work, as the condition of virtue requires. It is a family of human beings. In showing all of this, David’s painting is an unusual image.

Yet this is never seen by scholars who approach the task of reading with the predispositions we have noted. We reach here the quite remarkable conclusion that you cannot even lay out for yourself the options of possible meaning that this painting might have unless you are open to the possibility that, in reality, a family of fully co-operating members being who they are – a family fully intact and also exemplary – could look like this. What you believe (here, what you believe simply to be possible) opens you to seeing the truth before you. Or closes you.

In David’s Oath as read by the scholars we have a perfect illustration of how a painting can fit itself into the outlook they bring to it. Of the, essentially, two readings of the painting we have examined, were we to ask Which is more persuasive, we would have to answer, It depends on whom we are talking to.

9 | Lessons

What ‘moral lesson’ did David undertake to discover and teach, once his picture was hung in public?

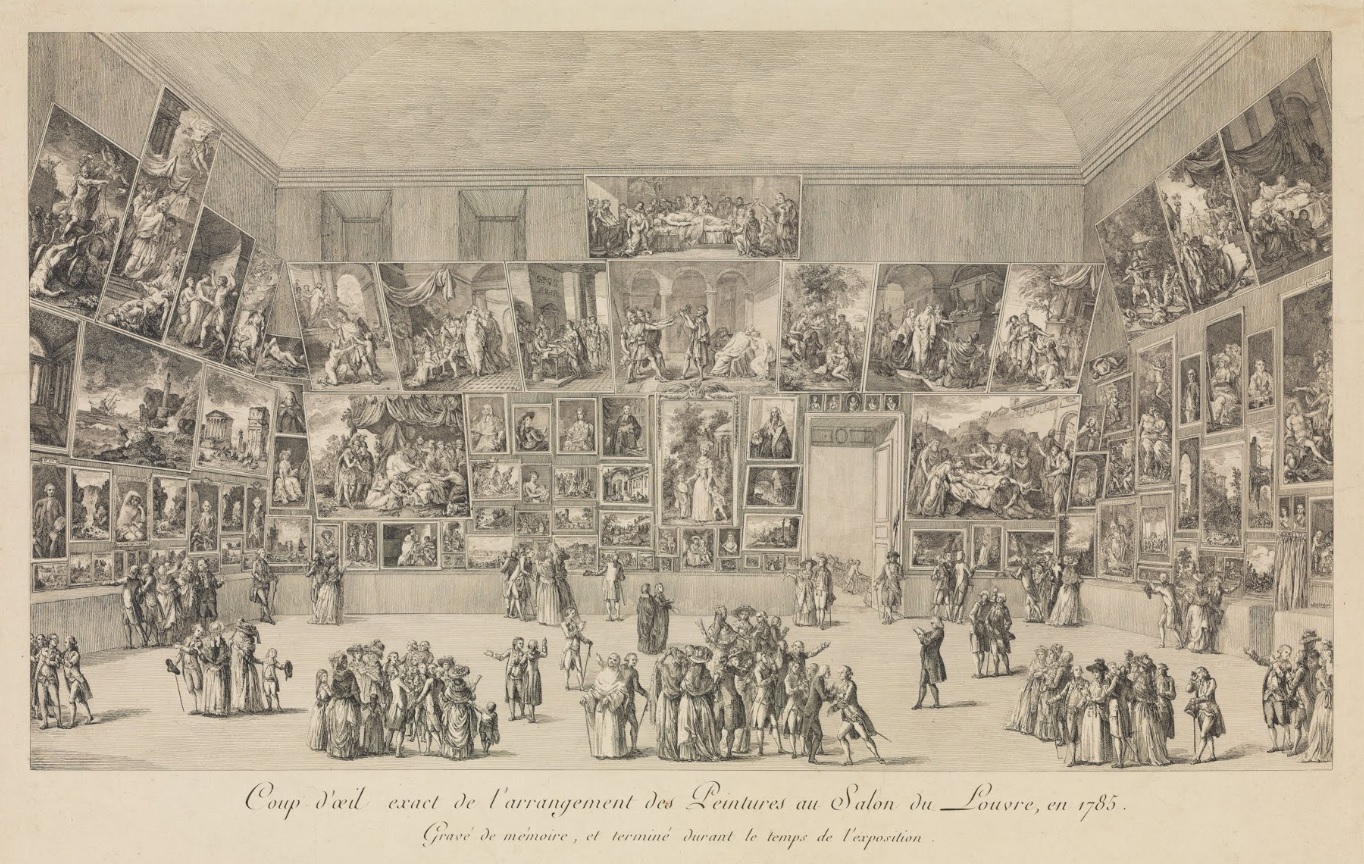

It was exhibited in Rome and then in Paris at the Salon of 1785, where in an engraving of that event you can see it hanging in the vast collage of pictures filling the walls. That it could get any attention in such a setting is hard to believe, but there it “excited great admiration” and was “a resounding success.” Upon the presentation of this work, David, says Eitner,

henceforth was recognized as France’s foremost painter.

Eitner, vol. I, 20, 21

What ‘moral lesson’? We have only the painting to tell us, via the understanding of the nature of the world that we have arrived at in the course of our lives. There is certainly a lesson that needs teaching, in perpetuity, about the ‘chiaroscuro’ of the world: the simultaneous darkness and light that accompanies acts that we judge to be in accord with the moral order, perhaps because they are. These can be acts of war.

The trouble at The Daily Wire (which may, I certainly don’t know, extend beyond this public bit that I am considering) appears to involve a loss of the understanding that David’s work affords.

It is surely right that Israel is retaliating against the enemy that attacked its citizens in October of 2023 (not combatants in a war but families in their homes). (I do not know the details of its retaliation, and certain kinds of target remain wrong, like the bombing of Dresden in the Second World War, but I know too little to say that Gaza is another Dresden; it is quite sufficient, however, to say what seems clear, which is that Palestinian non-combatants, children among them, have been killed.) In a family – and a corporation like The Daily Wire is like a family (families are a kind of ‘society’, where people enjoy each other in the shared pursuit of a common end) – there is surely a place for someone to mourn. Candace Owens is a mother, and spoke up to lament the maiming of Palestinian children. To voice the horror of such loss is an expression of humanity that comes easily to a mother; it is also a recognition that is due, due especially from within a human family in which there are separate and differentiated natures – powers and sensitivities.

Candace Owens is a mother, and spoke up to lament the maiming of Palestinian children. To voice the horror of such loss is an expression of humanity that comes easily to a mother; it is also a recognition that is due, due especially from within a human family in which there are separate and differentiated natures – powers and sensitivities.

The idea that being part of this family requires the women to behave like the men is – we have seen – simply an error. You may entertain such thinking, but, if you are exposed to this work of art – that is, are equipped to see what I have described – David’s depiction of a family in unity, harmoniously bearing the divided burdens of resolve and lament (the combined expression of their humanity), is enough to expose its poverty. If the image is properly read it exerts pressure on exactly that kind of thinking, sufficient pressure to leave it in pieces.

I have never been especially drawn to The Oath of the Horatii as a picture, but it is a work that I have had cause to think of many times (and this has happened once again). Taste steps aside to honour substance.

The company man who thinks that no family member who accepts the decision of war can indulge in any lamentation – agreement ‘with the men’ means talk that ‘stays on-message’, always assisting the justification of the war, saying nothing that might at all ‘harm the cause’ – David shows that to be hollow, even a grievous mistake. All that is just surpasses one thing that is just. It is, moreover, a blinkered non-acceptance of naturally different roles or sensitivities that are matched to and help take up the full range of human duties. The correct role for a woman is not silence. The man who complains that acknowledging horror makes his task harder has simply forgotten the whole that, actually, a family is needed to respond to. All of our ‘causes’ emerge in a reality that is greater than any human role can respond to. We are fools to think that the critical job is the one being managed by the man in the mirror.

Artist

Jacques Louis David (1748–1825)

Date

1784

Collection

Louvre, Paris

Titled there

Le serment des Horaces | The Oath of the Horatii

Medium

Oil on canvas

Dimensions

330 x 425 cm | 10 ft 10 in x 13 ft 11 in

Image source

Steven Zucker