Unknown love | Rembrandt’s Return of the Prodigal Son

In this essay,

• ILLUSTRATING A PARABLE

• ANOTHER REPRESENTATION & THE MORAL READING

• THE CAUSE OF THE SON’S RETURN?

• THE ‘REPENTANCE’ READING

• DYING & AWARENESS

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | Illustrating a parable

Three parables told by Jesus fill out Luke chapter 15: the Parable of the Lost Sheep, the Parable of the Lost Coin, and the Parable of the Prodigal Son. These stories make up the entire chapter – after two opening lines stating that “tax collectors and sinners were all drawing near to hear” Jesus, and this was disconcerting “the Pharisees and the scribes,” who “grumbled” that,

“This man receives sinners and eats with them.”

That observation, about receiving sinners, could not be more ironic in light of the parables to follow, all of which are about the reception given to sinners.

Because parables are symbols, however, they have depth and are not ‘about’ one thing only. These parables are also, all of them, about loss, ‘finding’, God, and joy, nor does this cover all the themes they address.

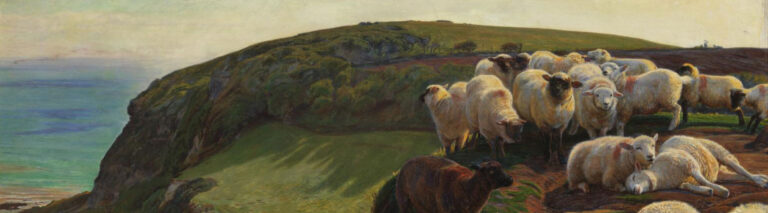

Though this is only the ninth work we have examined in this series, this is not the first time that we are looking at the illustration of a parable on ‘lost ones found’. There may be overlap between William Holman Hunt’s Strayed Sheep and a depiction of the prodigal son, yet there is scarcely any repetition of content. Variant parables on a single theme (or set of themes), such as we find in Luke 15, have the potential to single out different things.

The notable contrast in the three parables in this chapter would appear to be that, in the first two, it is the one who has lost something who is set before us. This is the only character whose shoes, so to speak, we are made to try on (the thing lost is simply that person’s treasure, and it does not provide another point of view in the parable). (If sheep experience being lost, that is omitted from Jesus’ story – Hunt’s painting is perhaps the best exploration of that theme: his image is an extension of the parable. It should be noted that the experience of being lost is in no way an irrelevant issue. Also that the coin of the second parable, of course, has no experience.) (If, therefore, the focus of the first two parables is the experience of the one who has a treasure, who is this person?)

But that is not the case in the third parable, whose focus is primarily the ‘thing’ lost: Jesus, having illuminated ‘finding’ in the first two parables now creates a second perspective, from the standpoint of being lost. A second kind of experience with which, perhaps, to identify.

PARABLES

The ‘perhaps’ of the last sentence seems to be a key feature of teaching by parables and stories. You may or may not find something, in a parable, with which to identify. A parable is a story and a story does not tell the listener where he is in the narrative. The parable has the effect that parables may have depending on your own determination of what place you have, if any, in the story.

Anyone who says You ‘ought’ to see that in this parable you are the X is using the language of the moralist, but the moment you moralize, ‘using’ a parable, you sabotage the parable. You have made a mistake in thinking that the authoritarian language of moralizing is superior to the parable of Jesus (that is, you have thought the parable is itself moralizing, but is moralizing unclearly; Jesus needs your help to deliver his message). That is nonsense.

You might think that what I am saying is disproved by David and Nathan. Nathan tells David a story; David condemns the man in the story – does not see himself in the story at all; Nathan says,

“You are the man!”

2 Samuel 12:7 ESV

But he is not telling David that he should see this. The parable has already done its work (set up the perfect and convicting parallel to David’s own actions); David has simply blocked out the possibility that he is hearing a parable, a story in which he is a character. All Nathan is doing, with the words, “You are the man!” is saying, It’s a parable. He is just holding up a mirror; David can see himself in the mirror, see perfectly well where he is in the story.

It is when you find yourself there in the story, when you see for yourself that that figure is you, that the parable begins to do the hard work it does – that is, revelatory work, breaking through hard walls. Should you be told, cogently, ‘This is you’ and you do not see it (that is not David’s situation) then the parable is dead, for you; it fails; it is a machine without power.

ILLUSTRATING PARABLES

I would like to move, however, to the topic of illustration. Suppose an artist chooses or is commissioned to illustrate a parable. We might see that their first task will be to choose a moment to illustrate – and why choose one moment over another? We can ask the same question about the depiction of Biblical stories of any sort: why lift this episode from the narrative?

You might have the view that a faithful depiction of a Biblical parable never departs from the text, but, first, verses of the text do not paint pictures – sometimes because, second, they are general statements. Take for instance Luke 15:13, which reads,

You might have the view that a faithful depiction of a Biblical parable never departs from the text, but, first, verses of the text do not paint pictures – sometimes because, second, they are general statements. Take for instance Luke 15:13, which reads,

the younger son gathered all he had and took a journey into a far country, and there he squandered his property in reckless living.

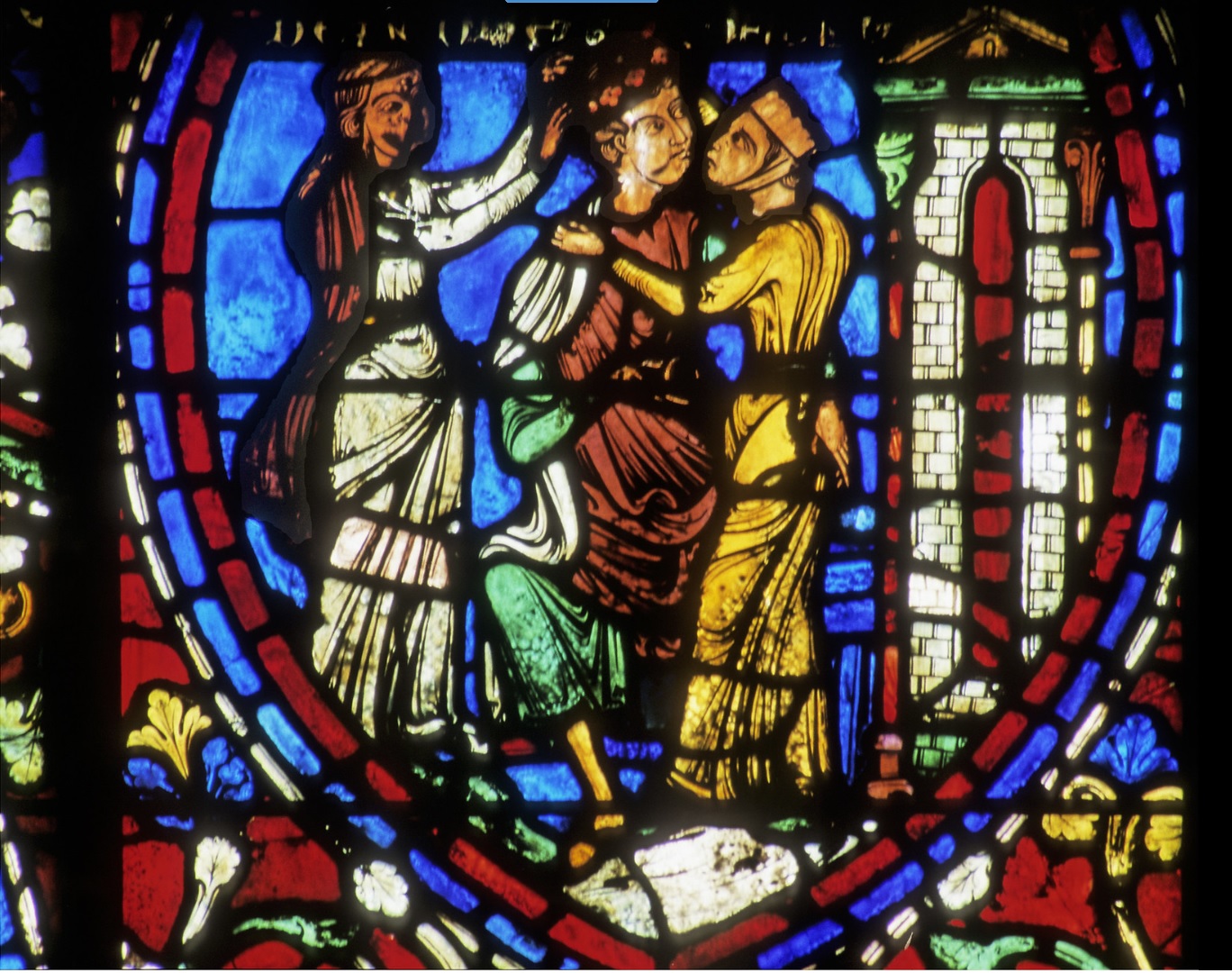

What is “reckless living”. At Chartres an entire stained-glass window is devoted to the parable of the prodigal son. It contains 27 medallions (9 rows of 3). The sequence runs: the request and granting of the inheritance (starting from the bottom left corner, two scenes), the second brother working, the voyage to the “far country”, and then in scene 5 the arrival at the gates of a city. There is no mention of a city in the parable, but how can you indulge in “reckless living” in the country?

Two harlots await him as he arrives at a city. His servant, dressed in blue, disapproving, appears to abandon his master.

Malcolm Miller, Chartres Cathedral,

2nd ed. (Andover: Pitkin, 1996), 78

Then follow six scenes of dining, “kissing and cuddling”, bed, gambling (and losing, as he is half dressed). Then begins his downfall: in scene 13 he is stripped and reduced to begging, then scolded or vilified (14), and physically threatened or chased away (15). In the next scene, the famine having struck, he sells himself to the “citizen of that country”; then in a peasant smock he feeds the pigs, and then (in scene 18, two thirds of the way up the window) he is shown sitting with pigs and staring blankly, in a pensive but frozen posture. It is the moment of realization.

The rest of the story plays out in and around the top quatrefoil or flower-shape. In the next scene he begins his return (he is on the road with a ‘pilgrim’s’ staff), then he is met by his father, and then follow six scenes of the festivities (slaughter of the fatted calf, roasting, clothing, music, feasting), and then, in the final frame, we see the elder brother, hanging back outside the home. (The three sections at the top show Christ flanked by angels.)

To do justice to the text, then, it must be imagined what it is that claims in the text (like “reckless living”) actually refer to.

2 | Another representation & the ‘moral’ reading

To move closer to the time of the work I wish to examine, consider one more representation of the parable. During a recent exhibition an entire room of the National Gallery of Ireland displayed six paintings on the parable produced by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682) in the 1660s, no doubt created to be hung together (as what is called a ‘cycle’, at a time when serial illustrations of religious subjects had become uncommon). Briefly, the six subjects selected by Murillo are:

1 The son receiving his portion (the son is shown collecting his inheritance in a fat sack, stared at by the elder brother, the father with mouth agape, hand raised in dismay, the son just transfixed by the money);

2 The son’s departure (waving his hat to his distressed parents, and siblings, as he rides from the family home);

3 The son feasting, etc. (in the scene of the son’s ‘prodigality’ or prodigious spending he is shown fancily dressed, enjoying a meal served on expensive silverware in the company of courtesans and serenaded by a musician).

The exhibition curators write,

“This scene marks the first time that the fall of the prodigal son was ever addressed by a Spanish artist, where values of decorum led to the avoidance of such imagery.”

National Gallery of Ireland, Murillo: The Prodigal

Son Restored (29 February 2020)

At the mention of ‘decorum’ (in relation to art), two applications of this term are, ‘what is morally suitable’ (the sense just applied) and ‘what is thematically suitable’ , where the concern is the proper placement of the work. Marriage-related themes, for instance, were suited to bedrooms.

A tapestry from the south Netherlands (of c. 1520 in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York) has the subject The prodigal son among the harlots, with every figure dressed in finery. I confess my inability to discern where this tapestry would have been thought fitting, though there was no doubt a logic to its commissioning and placement. It was either counted suitable, in some place where men gathered, to remind them of the fate of the prodigal son, or (as is also possible, since by this date there was a tendency to play with fire), an image of forbidden fruit just made for an especially appealing tapestry. (By the 1500s all that might be needed to win a morally dubious image a pass was a Biblical or moral allusion of some sort; examples are Susanna and the Elders by Bassano at al. and the many Venuses painted by Cranach.)

4 The son driven out (his inheritance spent, the hard times begin; Murillo too imagines rejection by harlots when the money has run out; write the curators,

“angry courtesans with furrowed brows chase the now-ragged prodigal from a brothel.”

5 The son feeding swine (alone in a desert-like setting the son kneels and confesses his sins, his hand on his heart like a penitent saint: the implicit text, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you”);

and finally, 6 The return of the prodigal son (outside the family home the father embraces the kneeling son; “the son locks eyes with his father, his clasped hands and forlorn eyes expressing genuine sorrow and regret”; an expensive robe is brought forth to clothe the son’s nakedness).

In the first half of this parable an artist could find a kind of Biblical catalogue of vice (avarice, gluttony, lust), by which the parable becomes a moral lesson, picking out vices to avoid. The second half (scenes 4 and 5, here) preach the practical hardships entailed by vice: the exit from the fool’s paradise, the wages of sin. The last image in this series shows the repentance and its wages.

Before we come to Rembrandt it will be worth singling out a key element given attention, in this parable, by theologians in the century before Rembrandt and that are still focused on today, that element being the turn that is pivotal in the parable. Rembrandt’s picture is not a cycle but a single image; he has singled from the entire story the return of the son.

That is, Rembrandt, so to speak, begins ‘past the turn’ in a parable that hinges on a turn. The Dutch Catholic writer and theologian Henri Nouwen explains that

the full title of Rembrandt’s painting is … The Return of the Prodigal Son. Implicit in the “return” is a leaving. Returning is a homecoming after a home-leaving, a coming back after having gone away.

Henri J.M. Nouwen, The Return of the Prodigal Son:

A Story of Homecoming (N.Y.: Doubleday, 1992), 34

For that return to take place, something must happen to turn the son around and what that is has been a significant focus in the way Christians have understood Jesus’ parable.

3 | The cause of the son’s return

Very recently I heard a sermon on this parable in which this element – the cause or trigger of the prodigal son’s return – was a central issue. In a sense the pastor had asked, when in the parable does the son change (and, accordingly, what is this parable telling us). – My purpose in going into this, it might help to know, is to enable us to lay hold of the reading that Rembrandt gives the parable.

There is a moral reading of the parable, which we have seen thus far. It focuses on the desires of the young man, whose eyes are full of the world and its goods. By that way of reading, the problem to be corrected (a correction prompting the son’s return) is either his behaviour (his vices) or his attitude (his fixation on ‘getting’, on self-gratification). In this way we are looking at a parable about desire, and its guidance or correction.

When the parable is read this way, at what point is the son changed – and what is that change? In fact his behaviour is changed for him (he is forced out of the life of pleasure against his will, by circumstances outside him; he has lost the means to live the life he wants). It is not externals, though, that are important; the thing to be corrected is his interior, and his attitude changes when he understands that he has sinned.

When does he understand this? In the sermon I mentioned the suggestion was, later than it seems.

The text of the parable specifies a turning point – that moment singled out, it seems, in the window at Chartres in which the son, staring at nothing with blank eyes, is forced to reflect, interiorly, on what has happened to him. According to the text, it appears that reflection freed him from the delusion in which he had been trapped. As translated in the NIV, for instance, the text reads,

When he came to his senses, he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have food to spare, and here I am starving to death! I will set out and go back to my father and say to him: Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son; make me like one of your hired servants.’ So he got up and went to his father.

Luke 15:17–20 NIV

If you pay attention to the sequence of the thoughts here (first, the food of the servants versus starvation; going home; what he will say to his father; and lastly repentance) an odd impression might arise. It is not difficult to hear the (repeated) words “I will say to him, ‘Father, I have sinned’” as a scheme.

“This isn’t contrition, this isn’t remorse, … repentance, … sorrow; this is a ploy. He camouflages his words to sound like remorse, but this isn’t it. The whole point of him coming home is that he is hungry. That’s what he wants. He knows that his father’s workers eat well so he thinks, I can just go home, and I can become like one of my father’s workers. This, friends, is a con.”

He was “self-serving” when he left home and “he’s returning home” under the same power.

Pastor Adams Townsend, Sermon on Luke 15 (21 April 2024)

By this reading, then, the talk of sinning in verse 18 marks no change of attitude. He may turn around physically and ‘go back’, but his heart is unaltered.

It is certainly possible to read the three lines Jesus devotes to this plan as, ‘This is what my pitch will be’. – I am inclined to quibble and say, but picture the young man’s actual situation: he is surely wondering whether his father will even receive him; isn’t the son anticipating real, in fact justified, anger for squandering the entire inheritance his father had built up. If he is planning his ‘move’, surely his thinking is, ‘This is how I will disarm him.’ – But I can see the charge that my quibble misses the point: a pretense of contrition, to soften his father up, is still a ‘con’ (a way to get what he needs).

What becomes obvious, however, at just this point, is how we are missing a central point of the text if we are talking entirely about contrition, repentance, a change of heart. Here in the text two things are aligned: sinning and loss of sonship. The ESV translation reads,

“18 I will arise and go to my father, and I will say to him,

A “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. 19 B I am no longer worthy to be called your son. C Treat me as one of your hired servants.”

And when he meets his father two parts of this are repeated:

21 And the son said to him, A ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. B I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’

Luke 15:17–19, 21 ESV

The action (sinning) is paired with an identity (sonship), the claim being that he has sinned, specifically, “against [his father]” and has lost his status as a son; he cannot expect to be received back into the family as what he formerly was. What might, however, be imaginable is indicated by C: he might be accepted by his father as a servant.

As soon as we notice this we see that in this parable, equal in importance to lostness (sinning, and the covetous, self-serving heart that drives it) is identity: the matter of understanding who and what you are. Also, were we to view sonship as linked to both behaviour and attitude as a reward for moral uprightness we would find ourselves thinking exactly the way the prodigal son does at this point in the drama: it is a status that you can lose; your relation to the father is altered by your behaviour and character (a heavy sinner must drop to the level of a servant). The two questions that the parable is raising, then, are:

- what is the relationship between sonship and sin/self-regard – specifically, can you lose it because of sin/a wayward heart?

- and, what is sonship – what is it to be a son to the father (or a daughter, a child of the father, a child of God)? – To put it another way, who are we?

At this point in the parable, notice, we have no answer to these questions. All the moral capital to be extracted from the parable has by this point already been extracted and posted in the moral images of the story, but it is only past this point in the narrative that the chief work of the parable will be done.

4 | The ‘repentance’ reading

There is a tradition of reading the verses we have just been looking at (18–19, 21) as an expression of contrition. The text of this parable in Luke 15 – “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you” – was in fact frequently invoked on the issue of repentance, the acknowledgement of sin. Note too this observation by an art historian, asking (of Christian art generally) whether

representations of biblical subjects reflect sectarian beliefs. The parable of the prodigal son is a vehicle well-suited to the purpose as it is a biblical text that is interpreted differently by Catholics and Protestants.

Barbara Haeger, “The Prodigal Son in Sixteenth- and

Seventeenth-Century Netherlandish Art: Depictions of

the Parable and the Evolution of a Catholic Image,”

Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 16:2/3 (1986), 128

According to Haeger,

Calvin … denies human action a role in the process of redemption, and in his commentary on the parable he specifically rejects the Catholic argument that the prodigal atoned for his sins through penance, thereby meriting his father’s forgiveness.

Haeger, “The Prodigal Son in Sixteenth- and

Seventeenth-Century Netherlandish Art,” 128

Can we accept this? That is, were there Roman Catholics who actually spoke of ‘meriting the father’s forgiveness’? Who actually said, first penance, then grace? In fact I am not interested to know, since I am certain that if there were such people they were bad Catholics – and we know that there are bad Catholics, bad Lutherans, bad Orthodox: and why does it matter what a mistaken person thinks? (The time for crushing feeble opponents is long past.)

On the question of repentance what are we to make, for example, of Albrecht Dürer’s engraving of the scene of the prodigal son among the swine, in which the wayward son is praying. This is an image tied to the verse of awakening (“he came to his senses”). Andrew Coates writes,

Dürer himself converted to Lutheranism, though as an artist he worried about its lingering iconoclastic sentiments. As a member of Nuremberg’s town council, he helped secure the city’s conversion to Lutheranism in 1525. Despite clear associations with the Reformation, Dürer was a complex figure, and it would be misleading to call him a ‘Protestant’ artist.

Andrew T. Coates, What is Protestant Art? (Netherlands: Brill, 2018), 44

The engraving, however, dates from around 1496, some twenty years before Luther’s 95 theses. Does this image, then, give us a Roman Catholic reading of the parable? And what would that reading be?

Where the issue is to understand what the son believes in saying, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you” (notice that here the earthly father is paired with a father, I think we are meant to see, in heaven), we have two possible readings:

- the son believes he has sinned (he has ‘come to his senses’ and is turning himself around, by contrition, as in Dürer’s image);

- the son does not believe (‘coming to his senses’ means figuring out how to escape from his predicament; he sees his father less as someone he has “sinned against” than as a source of bodily necessities).

The latter view we do not see in Dürer, who reads the prodigal son as a contrite sinner, not feigning repentance in order to survive. The repentance reading of the parable sees in Jesus’ story the tale of a man’s awakening to his own sinfulness; his free descent into vice and his recognition that what he has thereby done is sin against his father and also (apparent in Dürer’s engraving) sin against heaven.

I won’t go into the “sectarian” question, distinguishing Protestant from Catholic readings (on that, see Haeger). But one issue here is an issue important to Jesus. I have no idea which sect it is that warns,

You cannot just get up and return home, no matter how far you have fallen away; you are dead in your sin,

but it could not be Protestantism, because Jesus has framed the parable of the prodigal son to present us with a man who believes that he has lost his sonship: that is, he has wronged the father too much to recover his former place. If it should turn out that in the parable the son will be corrected on this point – that is, that he is not refused the grace that resurrects him from that death – then this is not an astute observation from orthodox theology; it is a serious confusion … about the nature of God. It is in fact the primary confusion that the entire parable is meant to correct!

Before we turn to Rembrandt one issue worth attention is that question of the cause of repentance. We must still figure out how to understand what “he came to his senses” means, and what the son is doing when he says “Father, I have sinned”. Does he mean this, or is he lying to get food?

5 | Dying & awareness

In the distant country the son understands that he is dying. Orthodox priest Maxym Lysack explains the young man’s actual situation, at that point at which he turns, repents.

While he was spending his father’s inheritance he wasn’t thinking about what he had or didn’t have. But when it was gone and he was starving, the moment of lucidity came. I have lost everything, to the point of death. Because, remember, it says in the parable he “would have” feasted on the food of the pigs but no one would give it to him.

Protopresbyter Maxym Lysack, “The Prodigal Son Restored,”

Christ the Saviour Orthodox Church, Ottawa (28 February 2021)

He understands that it’s the end for him. He can see only one thing he could do, to stay alive, should this plan work.

Back to the “ploy”. If the young man believes that he has to lie to his father, faking contrition to wheedle food, why would he think this? Why would he imagine that he cannot simply go home and eat? Because he understands that he has wronged his father. Lecturer in New Testament studies Kenneth Bailey writes,

For over fifteen years I have been asking people of all walks of life, from Morocco to India and from Turkey to the Sudan, about the implications of a son’s request for his inheritance while the father is still living. The answer has always been emphatically the same … the conversation runs as follows: Has anyone ever made such a request in your village?

— Never!

Could anyone ever make such a request?

— Impossible!

If anyone ever did, what would happen?

— His father would beat him, of course!

Why?

— The request means – he wants his father to die.

Cited by Nouwen

But this means that when he says, “Father, I have sinned”, he is not pretending. He knows, as Fr. Maxym puts it, “I’ve spoiled my father’s inheritance”: he has taken money that was his father’s to use until he died, and thrown it all away. It is impossible to picture the son showing up at home conscious of nothing but what he can get. He is dying because of himself; he knows how far he has fallen:

He’s caring for pigs. … To be looking after them and wanting to eat with them [– this can hardly be surpassed, in] the mind of a Jew, in terms of how revolting it is;

Lysack, “The Prodigal Son Restored”

he is returning home in a ruined state, thanks to his own ‘prodigality’. You can’t blow it all and not know who did this; the prodigal son knows that he is a prodigal son.

I am not suggesting that he now sees himself to be a worm. He could well be one of those people who, knowing he has done wrong, is nevertheless quite disinclined to take the measure of the wrong. He could be a minimizer, but it has become possible for him, stalked by death, to face up to things. One of the luxuries he has lost is the luxury of hiding the truth; he knows that he is going home in a very bad position, that he does not deserve to be counted a son.

We have already noted that self-knowledge is a theme in the parable: looking death in the face, and knowing how this has happened, he comes to his senses; other translations of verse 17 read,

“when he came to himself….”

Luke 15:17 ESV, RSV, ASV

His repentance is a form of understanding. To say that he repents, to the extent that he repents (acknowledges his degradation, turns around and goes home) amounts to no ‘Pelagian’ assertion that,

We don’t need any help, we can get home, we can make it on our own, God doesn’t have to come to us, WE return to God.

Kenneth Bailey, “Prodigal Son Parable, Part 1”

None of that is implied in saying that the son, who is dying, has been enabled – by his nature, reacting to his plight – to acknowledge certain facts.

He starts to be reasonable – I’ve lost everything, I’ve spoiled my father’s inheritance, becoming his son again is out of the question, but my goodness, look at how his servants live; they’re never hungry;…. Maybe … my father will be merciful enough to receive me back, as one of those. I wouldn’t starve,…. And so he makes that momentous decision – not just a decision but a move, because repentance involves movement not just thought. Repentance is something we do, not just something we consider. I will rise up, I will go, I will go to my father and I will tell him the truth:….

Lysack, “The Prodigal Son Restored”

If in Dürer’s engraving the son is praying just to survive – is praying that he have the strength to walk back to his own country, and not die or be murdered on the way, and that his father would feed him – would be just a means of food alone (he is aware that “becoming his son again is out of the question” ) – then he is turning, by a life-seeking power put into him by God, to his father and to God.

If Dürer’s prodigal son is just praying to survive, he is after all turned again to God, in a posture of asking. And let it be a God whom he scarcely believes in; the key thing is the “movement [that is] not just thought”: his turning around, to go back to his father, one of the people who brought him into the world. The key thing is the motion (of some kind) that opens him to what happens next. However slight his sense of God may be (as a man who has lived the way he has lived), the movement that he makes, walking back to the father, puts him in a position to experience the thing that happens next.

In all of the reckoning that he is enabled to do, which prompts his return journey, there is nevertheless something that he does not know about himself.

6 | Rembrandt & contemplation

As I used to teach in my course on art at Augustine College, the image in a Christian picture often singles out a specific line of Scripture. It is commonly singled out for attention in light of the image. The viewer of the work is meant to know exactly what verse he or she is seeing.

What do we imagine the point of this was? Surely nothing so pointless as to test your knowledge of Scripture. Knowing Scripture is unimportant if after snatching it, putting it in your grip, you do not consume it: if its content is not discharged, released into you. Identifying the verse points you back to the image in relation to the verse, and this sets in motion what the image was made to do, which was to “open to us the Scriptures” (Luke 24:32 ESV).

That habit of using pictures in Scriptural meditation is, however, virtually lost to us. If we come across these pictures in museums – not reproductions but the actual original – we have no training in what to do. Ordinarily we turn right away to the label, which we understand was put there to help us – but help us do what? If we do better than that, we play the game of ‘guess the subject’, working out the subject by what we see – but if identifying the subject is the endpoint, after all, the label gets there faster. Is there anything we are called to do here? We imagine the picture should make it happen … and we give it a once-over, looking for something to grab us – or for any particularly beautiful thing, at least, since we know that that is art’s business – and then we move on.

The idea of the use of the picture as a meditation on Scripture (or, as I have said more than once in this series, as a meditation on the world that is given to us as Scripture is given) is a custom or practice that Christianity has left behind, because Christianity (in Christian institutions) does not teach it. It could so (that in my view was the point of the art course at our Christian college). When believers commissioned or acquired these images to hang on their walls they did so with the intent of looking at them repeatedly in what used to be called contemplation, a major concern of Christian culture.

I could digress, to discuss the utter caricature of contemplation that modern history has now put in place (a kind of intellectual daydreaming) but this is too deserving a subject to be reduced to a digression. (Contemplation was never solipsistic activity but always ‘spiritual activity’, enrapturement by the spectacle of the spirit then being displayed.)

THE CHOICE OF ‘MOMENT’

When Rembrandt painted the parable of the prodigal son he chose the ‘subject’ of the son’s return, yet not the moment of reunion that is suggested in the text of the Gospel.

And he arose [in that distant land] and came to his father. But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him.

Luke 15:20 ESV

If that instant were literally depicted, the setting would be not the home but somewhere on the property; seeing the son from “a long way off” and then running, the father would surely have had time to leave his doorway, yet Rembrandt always sets the scene exactly there. Rembrandt had illustrated this parable thirty years earlier, in an etching of 1636 and then

in two drawings of the early 1640s; in all three the setting is the doorway of the father’s house.

in two drawings of the early 1640s; in all three the setting is the doorway of the father’s house.

In the painting, which is thought to have been one of the last works Rembrandt completed and is his largest treatment of the prodigal son (painted c. 1665 or 1669), that setting is still retained, though it is now very muted. (The steps of the house are clearly seen in the foreground, and at left, near the father’s elbow, the straight edge of a doorpost is detectable, with the curve of the archway above; the figure in shadow at the centre leans against and is partly behind the opposite doorpost.) This location is not a discrepancy. What the painting shows is the reunion, not the instant of reunion; moments, which have become so much more real in our age, for some reason, are of no actual significance at all. This is a parable both of reunion and of homecoming, neither of which is containable in moments.

In the painting, which is thought to have been one of the last works Rembrandt completed and is his largest treatment of the prodigal son (painted c. 1665 or 1669), that setting is still retained, though it is now very muted. (The steps of the house are clearly seen in the foreground, and at left, near the father’s elbow, the straight edge of a doorpost is detectable, with the curve of the archway above; the figure in shadow at the centre leans against and is partly behind the opposite doorpost.) This location is not a discrepancy. What the painting shows is the reunion, not the instant of reunion; moments, which have become so much more real in our age, for some reason, are of no actual significance at all. This is a parable both of reunion and of homecoming, neither of which is containable in moments.

As the parable is a narrative, a narration of events, the text continues in that fashion: the son speaks, the father answers by calling for clothing and a ring to be put on the son, and for a feast and celebration (the six scenes of activity at Chartres).

As the parable is a narrative, a narration of events, the text continues in that fashion: the son speaks, the father answers by calling for clothing and a ring to be put on the son, and for a feast and celebration (the six scenes of activity at Chartres).

And the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ But the father said to his servants, ‘Bring quickly the best robe, and put it on him, and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet. And bring the fattened calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate.

Luke 15:21–23 ESV

The parable’s ‘reunion scene’ closes with a statement of explanation, then a shift back to action.

‘For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.’ And they began to celebrate.

Luke 15:24 ESV

Rembrandt’s painting is tied to that one non-narrative statement, the statement by the father that explains the cause for celebration; “for”, he begins (meaning ‘because’), for “this my son was dead, and is alive again” – on this account we shall rejoice. And this turns us to face the meaning of the entire narrative, which begins with the lure of the world that took the son away and shifts into the loss of the son, the loss that has now been miraculously undone: the son who was dead “is alive again”.

7 | The allegory of being lost – or, a man ‘wasting his substance’ in a ‘far country’

Henri de Lubac condenses into a sentence some nine thinkers’ observations on understanding the Bible when he writes,

Scripture is like the world: “undecipherable in its fullness and in the multiplicity of its meanings”. A deep forest, with innumerable branches, “an infinite forest of meanings”: the more involved one gets in it, the more one discovers that it is impossible to explore it right to the end. It is a table arranged by Wisdom, laden with food, where the unfathomable divinity of the Savior is itself offered as nourishment to all. Treasure of the Holy Spirit, whose riches are as infinite as himself. True labyrinth. Deep heavens, unfathomable abyss. Vast sea, where there is endless voyaging “with all sails set”. Ocean of mystery.

Henri de Lubac, Medieval Exegesis, Vol. 1: The Four Senses

of Scripture (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1998), 75

Scripture has long been seen as interpretable in three or four ways, depending on whether you consider a literal reading (according to the ‘letter’) an interpretation of a text.

[The] allegorical sense [has been divided] into three kinds or into three tiered layers, as it were – moral, physical, and theological – which, together with the literal sense presupposed as a basis, would yield a fourfold sense.

Lubac, 121–22

I find myself wondering whether the ‘moralistic reading’ of the parable of the prodigal son we began with is part of the literal reading. If we have a child, who leaves home and throws himself or herself into the embrace of the world like the son in the parable, and who is, like him, broken down, we are not reading our child’s life allegorically. It seems a possibility that we might not read the parable at all, as a parable, if we do not get beyond the actions and motivations of the figures in the story: if we do not get to the meaning of these events.

Were we to ask, what are the ‘signs’ of the parable that ought to be interpreted, we would right away answer, the father and the son, but how are we to do that? The parable is the material that tells us who and what they are. We will not be able to interpret the father and the son if we do not see them in the light of the story we are given by Jesus. And what else does that story require us to interpret?

In Rembrandt’s painting we are seeing a return home, a return from the world. We must begin by interpreting “the distant country” and see the particular crisis that it causes.

The son took all his wealth (the “portion of goods” from the hand of the father, the son’s “substance”) to that “far country” (KJV) so as to use it: to spend and enjoy it. His wealth drew people to him and then, his riches gone, he was abandoned.

Many seek the favor of a generous man, and everyone is a friend to a man who gives gifts.

All a poor man’s brothers hate him; how much more do his friends go far from him!

Proverbs 19:6–7 ESV

The son was at first someone, on the terms of the world; then he was no one. When the text expresses that he was starving it does so in a rather unusual way: people denied him the food they gave to pigs.

He was longing to be fed with the pods that the pigs ate, and no one gave him anything.

Luke 15:16 ESV

He is not simply starving; he has become no one.

I will quote Henri Nouwen repeatedly; I cannot do without his insights into both the parable and Rembrandt’s painting. In 1983 Nouwen was visiting a friend and in the middle of their conversation noticed a large poster of the painting pinned to her door. He soon realized that he “was no longer paying much attention to the conversation; “I could not take my eyes away.” Two years later he was invited to join friends on a trip to the Soviet Union, where he knew he could see the painting itself, in the Hermitage in Leningrad, and in 1986 was able, thanks to connections of his friend, to spend three hours alone with it.

And so there I was; facing the painting that had been on my mind and in my heart for nearly three years.

That visit and the thoughts that flowed from it is the subject of an entire book, a rare extended reflection on a Biblical parable and a single representation of it, in which he wrote,

I don’t know whether the parable leads me to see new aspects of his painting, or whether his painting leads me to see new aspects of the parable.

Nouwen, 54

Nouwen pays attention to the prodigal son’s reduction, in the parable, to a nobody.

It seems that the prodigal had to lose everything to come into touch with the ground of his being. When he found himself desiring to be treated as one of the pigs, he realized that he was not a pig but a human being, a son of his father. This realization became the basis for his choice to live instead of to die.

Nouwen, 49

Though the son understood that he did not deserve to be treated as a son it was simply an undeniable fact that he had a father. He could make scarcely any claim on this relationship but that he was the son of a man could not be denied. However his father now regarded him, he would surely see him as that, as something. To those who would not give him the food of pigs he was nothing, but the son understands that he is not nothing. Nouwen writes,

The younger son’s return takes place in the very moment that he reclaims his sonship, even though he has lost all the dignity that belongs to it. In fact, it was the loss of everything that brought him to the bottom line of his identity. He hit the bedrock of his sonship.

Nouwen, 49

When everything else had been scraped away, there was bedrock.

This ‘sonship’ is as central a feature of the entire parable as the son. At this moment of the narrative all the son knows is that he is not nothing – which is to say, he is not the nothing that his reliance upon the world has turned him into.

Lostness must also be interpreted. When the text says, very centrally, “he was lost”, what does this lostness mean? In this parable to be lost is to be in the hands of the world, where this man

was no longer considered a human being by the people around him. He [now] felt the profundity of his isolation, the deepest loneliness one can experience. He was truly lost, and it was this complete lostness that brought him to his senses.

Nouwen, 48

To a relational being, to be nothing to anyone is annihilation.

He was shocked into the awareness of his utter alienation and suddenly understood that he had embarked on the road to death. … He understood his own death choice;.…

Nouwen, 48

THE TURN

Allegorically, this final recollection that he has a father is the cause of the turn – the reversal, the μετάνοια (the New Testament Greek word translated as repentance, meaning change of mind) – that is the return of the prodigal son. If the turn is simply called an ‘act of faith’ then we are not understanding the issue in the act of faith: the crisis of nothingness, and the recognition of a fact, that together accomplish an actual reversal – a reversal in both body and mind.

The son possesses some kind of identity in relation to the father; he is his father’s son. When Nouwen says the son, still in the far country, “reclaims his sonship” the nature of this connection is rudimentary: he has a father, he himself is something: ‘his son’, nothing more – whereas in the foreign land he was no one and nothing. It is this minimal but certain knowledge, writes Nouwen,

that finally persuaded him to turn back.

Nouwen, 46

THE WORLD

Nouwen has remarkable insights about the allegorical meaning of “the distant country” in this parable and the crisis of nothingness that the son’s life there has caused. The son was glad to remain abroad so long as his wealth lasted: his happiness was dependent on this; his acceptance by others was conditional. – What does it mean to enter into and be ‘of’ the world?

I give all power to the voices of the world and put myself in bondage because the world is filled with ‘ifs.’ The world says: ‘Yes, I love you if you are good-looking, intelligent, and wealthy. I love you if you have a good education, a good job, and good connections. I love you if you produce much, sell much, and buy much.’ There are endless ‘ifs’ hidden in the world’s love. These ‘ifs’ enslave me, since it is impossible to respond adequately to all of them. The world’s love is and always will be conditional. As long as I keep looking for my true self in the world of conditional love, I will remain ‘hooked’ to the world – trying, failing, and trying again.

Nouwen, 42

Belonging to the world and seeking to be someone in the world, is inevitably accompanied by experiences related to those conditions.

Before I am even fully aware of it, I find myself wondering why someone hurt me, rejected me, or didn’t pay attention to me. Without realizing it, I find myself brooding about someone else’s success, my own loneliness, and the way the world abuses me. Despite my conscious intentions, I often catch myself daydreaming about becoming rich, powerful, and very famous…. I am so afraid of being disliked, blamed, put aside, passed over, ignored, persecuted, and killed, that I am constantly developing strategies to defend myself and thereby assure myself of the love I think I need and deserve. And in so doing I move far away from my father’s home and choose to dwell in a “distant country”. … A little criticism makes me angry, and a little rejection makes me depressed. A little praise raises my spirits, and a little success excites me. It takes very little to raise me up or thrust me down. Often I am like a small boat on the ocean, completely at the mercy of its waves. All the time and energy I spend in keeping some kind of balance … [the] anxious struggle resulting from the mistaken idea that it is the world that defines me.

Nouwen, 41–42

It is this issue of who or what “defines me” that is at the heart of the parable, but this could be put in a more meaningful way, in a more familiar way, perhaps, if understood as how I see myself. Is it ever our own eyes? Is the question not, via whose gaze, whose attention to or estimation of us, do we regard ourselves? It is recognition by other people that stands behind so much of

what the world proclaims as the keys to self-fulfillment: accumulation of wealth and power; attainment of status and admiration; … sexual gratification….

Nouwen, 43

That that recognition is so often denied or withheld or withdrawn, says Nouwen, can

explain the lostness that so deeply permeates society.

Nouwen, 42

At the heart of the parable is the question – for all of us, not just those who ‘squander their fortune’ – Is there any relation to others that is truly free of frustration, uncertainty, and fear; is there any place that welcomes you, knows you as you are and invites you in? In fact the parable puts before us the idea that ‘wasting your substance’ is also a sign to be interpreted and its meaning is taking your life (your inheritance from the father) and giving it to the world, in exchange for fulfilment. The “death choice” is going to the world for fulfilment.

The parable of the prodigal (spendthrift, wasteful) son is, when interpreted, the parable of the lost and dying son (made clear by verse 24). Wastefulness is the literal reading (which indeed has moral import) but the concern of the parable is not moral; it is the fundamental logic of your life, the way you conceive living, define yourself and your fulfilment, the way you are unknowingly against life and squander all you have.

8 | Return from the world, arrival at …

When in the parable the son puts himself on the road home he has only a thin conception of what the sonship he now relies on (as his last hope) is: the bare fact that his father knows him to be someone, his son (his own father could not look at him, surely, and see someone less deserving of care than a pig).

But what Rembrandt in fact presents in his depiction of the return, the reunion, is an image of what sonship is – that is, what it means to be a child of God. We may be inclined to call ourselves children of God (because that is a Biblical concept) without ever awakening to its actual meaning: without ever truly leaving the far country; or without ever turning the experience of recognition back against our punishing addiction to the world – enjoying it but refusing to understand it. Nouwen writes that

‘Addiction’ might be the best word to explain the lostness that so deeply permeates society.

Nouwen, 42

At the literal level (illustration of the parable) Rembrandt does not show the moment of reunion; he does not present the drama of the starving son falling exhausted through the doorway (as in his drawing of 1644) and it is not son and father simply brought together again in one place, their home. He attempts to show instead what being ‘returned to the father’ actually is. In

Rembrandt’s portrayal of the return of the younger son … much more is taking place than a mere compassionate gesture toward a wayward child.

Nouwen, 43

Nouwen repeatedly attaches, to the father’s treatment of the son, the Biblical words that the allegorical reading of the parable has picked out for us:

“This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.”

Matthew 3:17 KJV

No one in the world was pleased with the son. Undoubtedly the father was never pleased with the son’s actions, but Rembrandt’s image shows no concern with actions (nor does that verse of Matthew that caps Jesus’ baptism); it affirms the belovedness of the son himself. In the parable the reception given by the father to his son is all surpassing. Nothing is withheld from him; what he is given is unsparing love, the fullest love the father can demonstrate, a love that the son is told to claim, made to claim (the clothes and the ring are put on him) – all in honour of what he is: the father’s beloved son.

In the hands on the son’s shoulders it is possible that Rembrandt has quoted a Psalm, which says (ironically),

In the hands on the son’s shoulders it is possible that Rembrandt has quoted a Psalm, which says (ironically),

You hem me in, behind and before, and lay your hand upon me.

Psalm 139:5 ESV

It is the exact Psalm that addresses the issue of a man’s identity, that marks the attention God gives to a man, seeing, knowing, and receiving him.

O LORD, you have searched me and known me!

(And still you embrace me.)

You search out my path and my lying down and are acquainted with all my ways.

(And yet you welcome me.)

Even before a word is on my tongue, behold, O LORD, you know it altogether.

Psalm 139:1,3,5–6 ESV

(Yet you acknowledge and call me yours.)

As usual, the title, which purports at least to name the subject, fails actually to do that, because the return of the son is itself the reception by the father, and it is also the son’s experience of this reception. One way to express the meaning of the parable would be to say that God’s love is as great as the love of the father who has lost his son, who has thought him dead, but who is given his son back and receives him with the joy akin to resurrection. But what we see in Rembrandt’s picture is the son held in a relation of sonship, total and protecting – that is, we do not have the act of a father; there is also the son … the one who is loved, loved in fact for what he is in the all-seeing eyes of the father! It is true, as Nouwen writes, that

More than any other story in the Gospel, the parable of the prodigal son expresses the boundlessness of God’s compassionate love.

Nouwen, 36

But in this parable the father

embraced him and kissed him

Luke 15:20 ESV

and the son received the love bestowed on him.

Thus Rembrandt shows very clearly that the image cannot be thought an image of God’s love only. Sonship is a relation to the father. Here the son is convinced that he has been received, wholly and totally received. We are seeing him submit himself to be loved in this total way.

It is an image of both loving and submission, but submission to being loved.

‘I AM THE BELOVED’, THE IMAGE

The son has come home from the world.

A voice … whispered [to him] that no human being would ever be able to give [him] the love [he] craved, that no friendship, no intimate relationship, no community would ever be able to satisfy the deepest needs of [his] heart.

Nouwen, 50

The son has experienced the world and seen his own image in the eyes of the world and experienced the father and seen his image in the eyes of the father. The father sees the father’s own likeness in the son; the son is not some other thing. – To be made in God’s image is to be made with the likeness of the father, who will see him and love him like a second self.

If the allegorical reading we make of a parable of Scripture finishes by comparing God’s love to the love of a human father then we can be sure that the parable is still not fully interpreted. When it is properly understood it will connect and illuminate deeper-than-human mysteries elsewhere in Scripture. When we read in Genesis 1,

And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness,

Genesis 1:26

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him,

Genesis 1:27

what does this mean? – Here is another use of the same expression, also from Genesis:

And Adam lived an hundred and thirty years, and begat a son in his own likeness, after his image; and called his name Seth.

Genesis 5:3

Does a son not resemble his father?

Sonship in the parable of the son who returns obliterates the gulf of distance and sin between you and God. ‘God is so surpassing a reality, and I am nothing and nobody—God is so perfect, I have done horrible things—

“I am the Beloved One on whom God’s favour rests.”

Nouwen, 41

God sees our likeness to Him, sees us as his children. The return of the prodigal son, the lost child, that is depicted by Rembrandt is, in the reunion Rembrandt chose to portray, the dawn in the son of a new understanding … of the nature of the father. A new understanding of the world comes through a revelation of the nature of the father. If we say, ‘of the nature of God’s mercy’, that cannot be wrong, but it does not speak to us to put it that way: we are fixated not on mercy but on life. In the disclosure of God’s love

the mystery of my life

Nouwen, 44

is cracked.

Home is the centre of my being where I can hear the voice that says: “You are my Beloved, on you my favour rests.”

Nouwen, 37

Life is not found anywhere but home, in the embrace of God, bestowing the very acceptance and life we crave.

The more I spoke of [Rembrandt’s] ‘Prodigal Son’, the more I came to see it as, somehow, my personal painting, the painting that contained not only the heart of the story that God wants to tell me, but also the heart of the story that I want to tell to God and God’s people. All of the Gospel is there. All of my life is there.… The painting has become a mysterious window through which I can step into the Kingdom of God. It is like a huge gate that allows me to move to the other side of existence,

Nouwen, 15

where there is life in abundance.

When I hear that voice [saying “I am the Beloved One”], I know that I am home with God and have nothing to fear. As the beloved of my heavenly Father, “I can walk in the valley of darkness: no evil would I fear.” … Having “received without charge,” I can “give without charge.” As the Beloved, I can confront, console, admonish, and encourage without fear of rejection or need for affirmation. As the Beloved I can suffer persecution without desire for revenge and receive praise without using it as a proof of my goodness. As the Beloved I can be tortured and killed without ever having to doubt that the love that is given to me is stronger than death…. Jesus has made it clear to me that the same voice that he heard at the river Jordan and on Mount Tabor can also be heard by me.

Nouwen, 39

REVELATION

In the revelation of God as the one who embraces us (an image we have seen before) we go home. This is a revelation of the nature of life and of our true relation to both God and the world. What Rembrandt presents is the son in a state of self-understanding: that he is ‘the beloved of the father’ – a moment foreshadowed earlier in the parable in the words “when he came to himself”. In Rembrandt’s painting, writes Nouwen,

The great event I see is the end of the great rebellion. The rebellion of Adam and all his descendants….

That is, the world to which man ordinarily flees is put at last into its true relation. In the painting the son’s back is turned to it, because he has turned himself to the father, and accepted the father’s assertion that he is something: his father’s beloved child. Nouwen writes,

It seems to me now that these hands have always been stretched out – even when there were no shoulders upon which to rest them. God has never pulled back his arms, never withheld his blessing, never stopped considering his son the Beloved One. … Here the mystery of my life is unveiled.… The blessing is there from the beginning. I have left it and keep on leaving it. But the Father is always looking for me with outstretched arms to receive me back and whisper again in my ear: ‘You are my Beloved,….’

Nouwen, 43–44

The son never knew who he was, what a child of God actually is. The celebration is great because the son who chose the road to death has found the way home, and this is some kind of miracle. Is this repentance? – Yes, in that it is a turn away from the world, but until he is in the arms of the father he does not know what anything truly is. It is only now that we can mention faith in a way that gives it the magnificence that in our understanding it so rarely ever has.

Faith is the radical trust that home has always been there and always will be there. The somewhat stiff hands of the father rest on the prodigal’s shoulders with the everlasting divine blessing: “You are my Beloved, on you my favour rests.” Yet over and over again I have left home. I have fled the hands of blessing and run off to faraway places searching for love! This is the great tragedy of my life and of the lives of so many…. Somehow I have become deaf to the voice that calls me the Beloved, have left the only place where I can hear that voice, and have gone off desperately hoping that I would find somewhere else what I could no longer find at home.

Nouwen, 39

This is a reminder that the painting has an entire right half, and that the parable is a story of two sons, a bad son and a good son.

To be continued

Artist

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606–1669)

Date

1663–65 or 1669

Collection

State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Titled there

Return of the Prodigal Son

Medium

Oil on canvas

Dimensions

205 cm x 262 cm | 80.7 x 103 in

lower Hermitage photo, Ken Davis on Flickr

. c