Love of society | Van Gogh’s Night Café Terrace

In this essay,

• HUMAN MIRACLES

• VAN GOGH’S ‘CAREER’

• WHAT DO WORKS OF ART MEAN?

• THE SETTING OF LIFE & A PICTURE OF SOCIETY

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | A colour motif

The picture’s immediate attraction is its contrast of essentially two colours: a strong framing blue and a central mass of yellow, a yellow that shades within its zone to both orange and yellow-green. I appreciate how deficient are descriptions like this of what is in a painting – in this case, of a colour motif, an attractive contrast of colours. What is said is so crude, beside what we can see in the picture itself, as to seem inevitably implausible. It sounds especially crude if it is said about a work by Van Gogh, that miracle man of colour.

It is impossible, in connection with Van Gogh, not to think in terms of miracle, though I suppose I should acknowledge that not to do so is in the most common thing of all. I should say, it is impossible the more your idea of miracles extends to actual miracles.

HUMAN MIRACLES

Habitually we define miracles as departures from the laws of physics – essentially giving all our attention, on the topic of miracles, to nature and none to the accounts of miracles that are the great cause of talk about miracles (for those who have not experienced them). That restriction of attention is rather hard to explain.

The miracles mentioned in the Gospel of John alone defy not just physics but biology, space, and time. They are “signs” of something – of someone, rather – who has mastery over all of creation (and all the causality that ‘our world’ manifests) … someone, more specifically, who has power over

the very things that human beings cannot change or create.

Merrill C. Tenney, “Topics from the Gospel of John:

Part II: The Meaning of the Signs,”

Bibliotheca Sacra 132 (April 1975), 158

This being so there are more kinds of miracle than the ones that come to our science-focused minds.

If we see the category of miracle as a circle drawn around the ‘impossible to explain’ rather than ‘actions that violate physical laws’ – ‘impossible’ meaning truly that (not something ‘as yet unexplained’ but something that cannot be explained via any of the dynamics and causes belonging to our world as we ordinarily understand it) – then … there are also human events to look at, impossible happenings in a domain apart from nature.

(It may be worth noting, parenthetically, that at one time this was clearer. Miracles were “works beyond the competence of all natural powers,” and God has performed such works,

in the wonderful cure of diseases, in the raising of the dead, and what is more wonderful still, in such inspiration of human minds as that simple and ignorant persons, filled with the gift of the Holy Ghost, have gained in an instant the height of wisdom and eloquence.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles,

trans. Joseph Rickaby (The Catholic Primer, 2005), 1.6

What Aquinas is specifically referring to here is faith: people were endowed with “truths of faith.” We do not pick up such convictions by the ‘competent use of a human power’ but hold them by grace. They are, says Aquinas, “above reason”. That after Christ’s death people

flocked to the Christian faith, wherein doctrines are preached that transcend all human understanding, pleasures of sense are restrained, and a contempt is taught of all worldly possessions. That mortal minds should assent to such teaching is the greatest of miracles,…. (1.6)

Such was, once, the understanding of miracles.)

In our time, of course, from the very moment attention is shifted to human achievements many people become certain that, just because we are talking about things done by mere people, explanations are available in the terms of human psychology or environment; some combination of ‘factors’ will explain it. We might, however, note that, unaccompanied by argument, this conviction is more or less of a groundless assumption. What does this ‘confidence in explicability’ actually rest on? Perhaps on a predisposition to stamp out every spark of mystery so that the conception of the world this person has formed, out of his favourite material, does not burn down.

But aren’t there impossible happenings in human lives (not just in human bodies)? How does a person turn his life around? What causes the scales to fall, when they do? What explains the saints? What explains Van Gogh? No human being could ever set out to do what Van Gogh did by discerning the means and the formula for what Van Gogh accomplished. ‘Ten thousand hours’ and ‘wood-shedding’ certainly explain some achievements, but what Van Gogh achieved is impossible to explain.

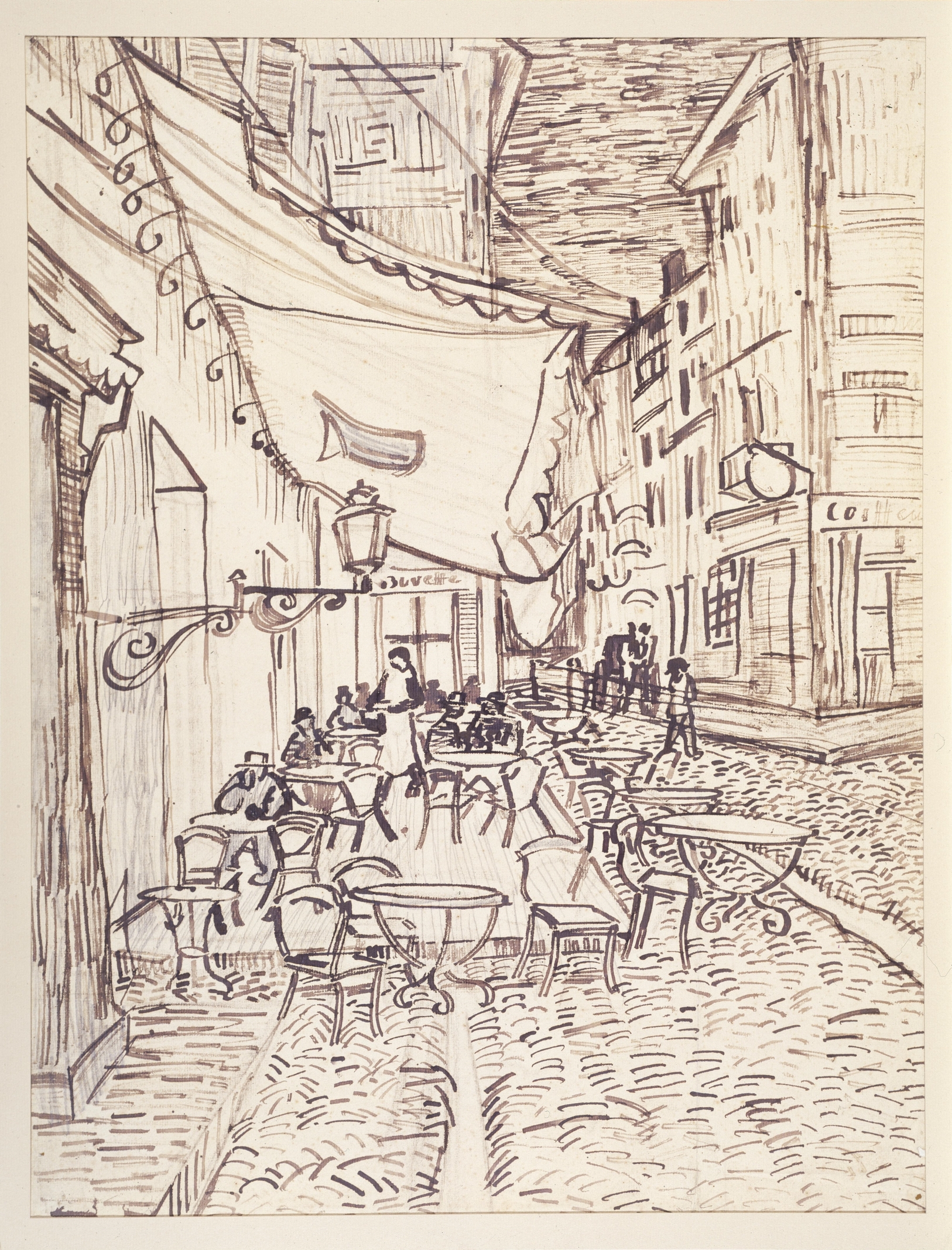

2 | Van Gogh’s ‘career’ as an artist

Vincent van Gogh began to draw and paint – began drawing, in a visibly halting fashion – in 1880 and he died in 1890. All of his work comes from a single decade of his life; ‘early’ Van Gogh is dated 1881. Moreover, for half of that decade he was engaged chiefly in drawing – painting also but in a manner that was very linear and like his drawings – working fairly exclusively either in monochrome or in a tight range of earthen tones. His work in this period is quite consistently sombre. But then Van Gogh opened up his palette and became an absolute and virtually instant master of colour.

This decade of Van Gogh’s life as an artist can be divided into roughly two periods of equal length. During the first of these, to 1885, he wrestled with temperamental difficulties and sought, as people have been inclined to put it, his “true means of self-expression”. They must speak in this way given the lingering hold of this pervasive distortion of the nature of art, but is that the right way to put it? I have my doubts. What we can surely say about this half of Van Gogh’s life as an artist is that it was a period of learning aligned with the concerns that had motivated his work, eventually frustrated, in Christian ministry.

The second half of his career, from 1886 to 1890, is sometimes called a period of rapid development and then fulfillment, but this characterization is again hampered, now by ‘art historical’ thinking. When the discipline taxed with understanding art is ‘art history’ then, by that token, you are stuck with ‘development’ (or decline, or stasis) as the thing furnishing your terms of understanding. This is not so much limiting as blinding.

UNDERSTANDING ART

Understanding art – understanding individual works of art but also what individual works are doing and showing and thus what art itself is doing and showing – is not a scholarly enterprise, one that lifts its expertise from the historians, emulating the methods of those who work with documents. Understanding art is the work of an ordinary person who is the member of a literate culture. Such a person is simply one who reads what exists to be read, in the ordinary human conduct of understanding his or her own existence.

If we adjust, then, to obtain a better sense of this second half of Van Gogh’s ‘career’ as an artist – and, once again, we do not have the right term for what Van Gogh was doing. – What kind of ‘career’ is it that produces more than 700 drawings and 800 oil paintings and manages to sell only (literally) one or two? Such a ‘career’ would belong to a failure, which Van Gogh was not. He was not working for his time. But I digress – if for the good reason of noting, again, that there is something to understand in the work of an artist like Van Gogh that cannot be understood by models borrowed from other kinds of human business. – If, then, we look more freely at the last half of Van Gogh’s decade of work we do not have ‘achievement’ or ‘finding his style’ after floundering or dissatisfaction. Van Gogh’s earlier work has a complete integrity, an accompanying mark of achievement in its own right, and numerous great works of a discrete kind. The focus of that early work is human beings, their plight, their nature; the light cast, in the work, on this subject matter is dim.

But in the last half of his working life Van Gogh’s focus quite suddenly shifts and colour arrives – all the colour that there is, it seems – and the scene in Van Gogh’s work is flooded with a harmonious light. One could say that this is simply a ‘new range of colour harmonies’, that the harmoniousness is just colouristic, literally. But it makes quite a bit more sense to say that what we see in this body of work is five years of unrelenting delight in the world, communicated via colour. (That is, something glorious in the world, which he had not found in human relationships, will not let Van Gogh alone.)

The world on view in this entire period of work (work that is now largely a body of ‘landscapes’) comes to Van Gogh as a kind of revelation. So different in outlook and tone are these two periods of work that it almost appears the output of two different artists. It is possible, indeed, that at a certain point Van Gogh himself came to inhabit a different outlook.

It is one that we see in this picture, which hangs in a Dutch museum. On the webpage of that collection devoted to this work, the curators have written essentially the same words I opened with above – I and the curator have converged on the same observation.

The most eye-catching aspect is the sharp contrast between the warm yellow, green, and orange colours under the marquise and the deep blue of the starry sky, which is reinforced by the dark blue of the houses in the background. Van Gogh was pleased with the effect.

“Caféterras bij nacht (Place du Forum),

c. 16 September 1888,” Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

This “contrast” is, indeed, the most visually arresting aspect of the picture, an immediately evident “effect” indeed.

THE APPEAL OF A COLOUR MOTIF

An ‘effect’ of this kind, in painting, is something like the ‘hook’ of a song, which is the individual song’s distinctive and engaging motif. I am wary of noting this as, I suspect, the actual nature of the song ‘hook’ of a isa thing not so easily summed up. I expect a ‘hook’ is very often quite a bit more than a mere distinguishing motif, on account of its actual musical content, but (these remarks on the record) it is right to call this arresting contrast of yellow and blue the painting’s hook, the immediate appeal of the picture – to switch the metaphor, its attractive quality.

I am alluding now to fashion: to the colour contrast in an outfit that makes that outfit get attention, sing. It may seem that, drifting into fashion, I am lowering the importance of the painting’s “eye-catching aspect” (its blue-yellow contrast) but in fact I am raising it.

A contrast of colours – a specific contrast of this cerulean blue and that chestnut brown – can be the thing that entirely makes an outfit, is the essence of this look. And in talking about ‘making the look’ we are talking about an achievement, a winning combination. It is this that is beautiful: this very contrast, or rather the harmony of this contrast. It attracts attention to itself: the way one colour fits the other is itself a cause of joy.

A contrast of colours – a specific contrast of this cerulean blue and that chestnut brown – can be the thing that entirely makes an outfit, is the essence of this look. And in talking about ‘making the look’ we are talking about an achievement, a winning combination. It is this that is beautiful: this very contrast, or rather the harmony of this contrast. It attracts attention to itself: the way one colour fits the other is itself a cause of joy.

But in fashion the beauty of an ensemble is not confined to these affecting harmonies. The real beauty of fashion lies in the woman actually wearing this harmony, moving through her evening so dressed and embellished. It is the clothing worn by a human being going about her life, adorned in this harmony, that is the end; that is the event of ‘being dressed’. The significance of the motif is raised when this harmony of colours lends something to the whole it is part of.

The substance of Van Gogh’s picture is not the colour motif that is its hook. That “eye-catching” contrast of colours embellishes a whole whose nature we will have to assess.

Mind you, it is not impossible for the substance of a painting to be a colour motif; I can well imagine someone saying that the whole to which the motif lends its charm and beauty is Van Gogh’s painting, the work of art – and such a thing, I agree, could be the essence of a picture and enough of a contribution. If a painting delivered the particular beauty and power of an arrangement of colours, this would not be an empty contribution to flourishing. But to say that of this painting would be an error. There is a whole, here, that is rather more.

3 | The Night Cafe

The painting we are looking at is not dated but evidence from Van Gogh’s letters shows that it was painted in September of 1888. In February of that year Van Gogh moved to Arles in the south of France; in a letter written at the start of October he mentions a painting that he had made of

the night café where I stayed, with lamp effects – painted at night.

Vincent van Gogh to Eugène Boch, 2 October 1888

It would appear that Van Gogh had rented a room on these premises before moving into the house he leased that September. The work “with lamp effects” that he refers to is a painting of the café interior.

THE PAINTING OF THE CAFÉ INTERIOR

In this particular work, Van Gogh explained in another letter, he had returned to a motivation of his earlier work: the depiction of people who are trapped, people for whom life has gone wrong. He wrote to his brother Theo that,

In my painting of the night café I’ve tried to express the idea that the café is a place where you can ruin yourself, go mad, commit crimes. Anyway, I tried with contrasts of delicate pink and blood-red and wine-red. Soft Louis XV and Veronese green contrasting with yellow greens and hard blue greens. All of that in an ambience of a hellish furnace, in pale sulphur.

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 9 September 1888

In a letter written the day before he had explained more fully how he had painted it, and gave an even more detailed account of the colours he had employed “to express” what was driving him.

For 3 nights I stayed up to paint, going to bed during the day. … the painting is one of the ugliest I’ve done. It’s the equivalent, though different, of the potato eaters. I’ve tried to express the terrible human passions with the red and the green. The room is blood-red and dull yellow, a green billiard table in the centre, lemon yellow lamps with an orange and green glow. Everywhere it’s a battle and an antithesis of the most different greens and reds;….

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 8 September 1888

Because of these remarks on its content this painting is one of Van Gogh’s most discussed images. People feel themselves to be on very solid ground, talking about the meaning of this painting – indeed, in claiming that it has a meaning. What, by contrast, is the meaning of the landscapes, still-lifes, and portraits that chiefly absorbed his attention in this later period of his life?

Van Gogh himself seems to have made some such classification of his works. While he was still at work on the café interior he mentions a kind of fluctuation in his thinking.

Exaggerated studies like the sower, like the nightcafé now, usually seem to me atrociously ugly and bad, but when I’m moved by something, as here by this little article on Dostoevsky, then they’re the only ones that seem to me to have a more important meaning.

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, on or about 11 September 1888

In other words, because such pictures “usually seem[ed]” to him “atrociously ugly and bad” he very rarely painted like this giving this kind of attention to human misery; he was focused on something else, presumably not “ugly and bad” but beautiful and good. Yet he was reminded (by something he had read about either Dostoevsky himself or his work) of the “importance” of works with such a “meaning”.

A QUESTION ABOUT MEANING

Keen to move on to our picture of the café, I would be glad to sidestep the question of Van Gogh’s success in this picture, only this happens to be a question quite relevant to a concern that we have, about the picture that is our focus. This picture, says van Gogh, has an “important meaning” – “a more important meaning,” even, than the more attractive pictures he was concentrating on; in fact Van Gogh has noted that the “ugly” pictures “are the only ones that seem to me to have a more important meaning”. What meaning, if any, do the ‘beautiful’ ones have (among which I class our picture)?

What is it that a picture actually does say? is perhaps the pivotal question of this essay.

In answering this it is the picture that we have to listen to, not the artist. We have, I suggest, reason to doubt Van Gogh’s comments on the meaning of his painting of the café interior.

Van Gogh, I believe, was dabbling here in a modern confusion (one that was soon to become an essential dogma), to the effect that The artist decides the meaning. The more prone you are to accept this dogma the more you will find it difficult even to imagine an alternative (the artist as opposed to what ). Who else could it be but the artist, you will think.

But the ancient answer was, the art – that is, the artist’s own art or skill, as manifest in the work he has done. Does the artist know how to accomplish what he wishes, and does the work that he has made do what he intends? It looks to me as if Van Gogh has told us what he wants his work to mean, but that the painting he made does not co-operate in meaning it.

THE DOGMA ASSERTED

It is rather interesting to find this dogma asserted by a well known art historian with reference to this very painting. Irving Lavin once explained what his academic discipline was.

I … define art history as a natural science of the spirit. … Like any science, my natural science of the spirit is based on certain assumptions.

Anyone seriously concerned with the study of art, in the discipline devoted to art, writes Lavin, must – simply to achieve whatever a science of the spirit achieves (it is frustrating that Lavin does not bother to name this, though perhaps, given his talk of “science”, we are to understand that it is ‘knowledge’) – again, a person participating in this science must adhere to certain governing assumptions, one of which

is that everything in a work of art was intended by its creator to be there. A work of art represents a series of choices and is therefore a totally deliberate thing.

Irving Lavin, “The Art of Art History: A Professional Allegory,”

Leonardo 29:1 (1996), 30

Lavin is not saying the obvious (that an artist intends what he intends) but that the artist’s intention is effective, is, as a matter of ‘deliberate statement’, directly transferred to the work. (Yet there is something off about this: unintended meaning thwarts our deliberate intentions all the time.)

Were we to ask, says Lavin, whether Van Gogh’s painting “does communicate the intended feeling” we are in no position to say No just because we do not see the message it has (has by virtue of this deliberate act of meaning). He writes,

surely there is no failure to communicate here, only a failure to comprehend. (30)

But the artist (said the ancient world) is not a god but a maker of things, and only if he has the ‘art’ or techne or know-how does he make a thing that means what he wishes it to mean. What the work of art will always do is say what it can say: what it is actually configured to say. (Whether particular people are hearing it, are equipped or deficient of hearing, is a further and separate issue.)

We do see in Van Gogh’s picture the nakedness of an over-lit room, but the hapless-looking old Frenchman appears more affable than desperate, and Van Gogh’s colour cannot help but lend this graceless space a certain charm, and the flowers sound a note of hope.

In mid September of 1888 Van Gogh wrote to his sister that he had completed this painting, which he had evidently continued to work on since the 8th, when had given it three nights. He speaks now of what he would like to do next.

I’ve just finished a canvas of a café interior at night, lit by lamps…. The room is painted red, and inside, in the gaslight, the green billiard table, which casts an immense shadow over the floor.

… I definitely want to paint a starry sky now. It often seems to me that the night is even more richly coloured than the day, coloured in the most intense violets, blues, and greens.

Vincent van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, 14 September 1888

He wants to get out of the room he had disliked, out under the night sky, and the picture he then painted was of the terrace of this same café.

4 | The Night Café Terrace

It is undated but was likely completed through the second half of September 1888 and like a related picture done at this time it may have been painted on the scene at night. In a letter of the 18th Van Gogh mentions “the two cafés” he has just painted in a list of newly completed works, at the same time describing what he is chiefly responding to in this phase of his work.

I already wrote to you early this morning, then I went to continue working on a painting of a sunny garden. Then I brought it back – and went out again with a blank canvas and that’s done, too. And now I feel like writing to you again. Because I’ve never had such good fortune; nature here is extraordinarily beautiful [– Van Gogh’s emphasis]. Everything and everywhere. The dome of the sky is a wonderful blue, the sun has a pale sulphur radiance, and it’s soft and charming, like the combination of celestial blues and yellows in paintings by Vermeer of Delft. I can’t paint as beautifully as that, but it absorbs me so much that I let myself go without thinking about any rule.

That gives me 3 paintings of the gardens facing the house. Then the two cafés. [Etc.]

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 18 September 1888

In the “celestial blues and yellows” that are this painting’s immediate appeal, what is presented in “the harsh gold of the gaslight” (a fitting phrase from a letter of the 29th) is not so much an effect of light as the glory of colour. I am not saying that Van Gogh doesn’t paint light but that he does paint light: he paints its colour. A particular remark (on the colour of night) that he had made a couple of weeks earlier to his sister, he repeated almost exactly to his brother:

It often seems to me that the night is much more alive and richly coloured than the day.

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 8 September 1888

Van Gogh is engaged in honouring and signalling these glories and marvels that were being given to him (“I’ve never had such good fortune”) – given to all the people of Arles, as the setting for their lives. To paint it in this way – with these colour harmonies that are at play in everything Van Gogh is now doing – is to say that the setting is not a mere stage or platform, a bit of structure, like the setting of a gemstone, subordinate to the main thing (the action that is our lives). Rather, the glorious order of the world is something into which our lives fit. There is a whole that our lives are part of and this whole is glorious.

THE SETTING OF LIFE

Van Gogh was saying something like this three years earlier when he brought up the Baroque-age painter Nicolas Poussin:

As for Poussin – he’s a painter who thinks and makes one think about everything – in whose paintings all reality is at the same time symbolic. In the work of Millet, of Lhermitte, all reality is also symbolic at the same time. They’re something other than what people call realists.

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 4 October 1885

That is, realism does not get at something fundamentally meaningful in the nature of the ‘backdrop’ of human lives.

There are interior spaces – strictly man-made arrangements, as we have seen (the café interior with its garish light and hard shadows) – where people face derangement and collapse, but there is another pole, another stage, far removed from and opposite to that, which instead might be a place for flourishing. And so many of these places are human places: gardens, houses, farm plots, orchards. As a category for depictions of this, ‘landscapes’ is not specific enough.

We do not have in Van Gogh’s work of this era any contrast of nature and man of the sort introduced by Rousseau and perpetuated by the Romantics chiming in with Rousseau’s negative verdict on civilization. The scene in Van Gogh’s Night Café Terrace, even if the light is artificial and, says Van Gogh, “harsh”, is a scene of peace, in which the townspeople of Arles sit in each other’s company for a meal or a drink and walk the streets. In the same letter to Theo of 9 September already mentioned, about his painting of “a place where you can ruin yourself,” Van Gogh talks of his plans for the house he intended to rent and make ready for guests.

One of these days you’ll see a painting of the little house itself, in full sunshine or else with the window lit and the starry sky.

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 9 September 1888

In the Night Café Terrace we see both those elements, homey lit windows under a starry sky. Our question has been, what does it say: what is this picture configured or equipped to say?

AN IMAGE OF SOCIETY

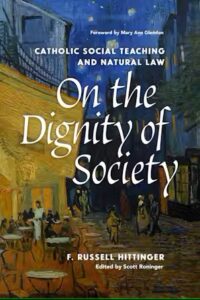

Van Gogh’s Night Café Terrace came to my attention as the cover image on a book slated for publication in July of 2024, Russell Hittinger’s On the Dignity of Society. (Whether this is the actual cover or a stand-in for the publisher’s catalogue before the actual cover is decided, as is sometimes done, I do not know.) It is certainly an interesting choice.

The more you think about the nature of a society, which Hittinger’s book explores, the more intriguing is the idea of a fitting illustration. What is a good image of society? That would certainly depend on what a society is.

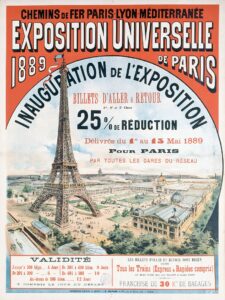

What Hittinger has already written on this subject tells us, if I might attempt a summary, that a society (in the Catholic tradition of thought that is his subject) is a more particular thing than the totality of people we live among or the oddly vague thing we mean by ‘community’. In the fall of 1888, when Van Gogh was painting the pictures we have been looking at, the Exposition Universelle was being planned, opening in May of 1889 in celebration of the centennial of the French Revolution.

We tend to forget that this was the occasion for which the Eiffel Tower was conceived, indeed, that the social upheaval of the Revolution and the offspring rebellions that perpetuated this transformation (noted in an earlier essay) were viewed with favour. Hittinger notes,

The theme song of the exposition included the line “I have destroyed the old laws, I bring hope.”

Russell Hittinger, “The Three Necessary Societies,”

First Things 274 (June/July 2017), 20

In 1888, the year we have been lingering in, Pope Leo XIII began to prepare a reflection on “the spirit of revolutionary change” that had “passed beyond the sphere of politics” and affected the ordering of society. In 1890 he issued the encyclical Rerum Novarum, on “the natural tendency of man to dwell in society”. As Hittinger explains, its chief observation is that

we live in societies, not in social movements, political parties, field hospitals, Starbucks, or in Euro-style cultures without boundaries. (21)

Associations like those just listed do “enjoy a truly social principle” (we enter into them for common ends and enjoy participating in them together for these ends) but we exit such ‘societies’, which can change and even disappear, without putting in peril the achievement of our human purposes. There is beneath these a set of societies that we do not exit; we dwell in them (while those other forms of association are, by contrast, more like instruments that we use). And when they are changed or undermined we have not simply problems attaining the ends of those associations but problems fulfilling the ends of our lives. These are necessary societies, and they are the family, civil society (membership in a governed order, a society of families), and the Church (tending human ends in the supernatural order). As Hittinger puts it,

A demise of the necessary societies would mark a social calamity. (20)

Truly, it is the Van Gogh that I am interested in, a picture that drew nothing from a document being written while it was painted, but in that document Leo XIII said that “Nothing is more useful than to look upon the world as it really is,” and we can do that by turning back to the painting.

We are looking at a picture of Van Gogh’s Starbucks, which is not one of the necessary societies but nevertheless possesses that essential ‘social’ element that we fail to capture when we talk casually about community. In the café you do not just come together; you come together to share the benefits that the café affords, one of which is the pleasure of being together with others. I recall a time when I used to frequent a café – when I was an habitué of such an establishment, when I made a habit of sitting there in the afternoon after I had done a good morning of work writing my thesis. I was living alone and the motivation to be there was not just the coffee, or the excellent Reuben sandwich that I still remember, or the stone walls and large windows; it was, I recall, to sit among people.

The people were strangers. I had no expectation of ‘socializing with’ (speaking to) people at other tables; I was no good at talking to people and had by then, mercifully, outgrown ‘fantasies of meeting’ so that I could just relax and enjoy my solitude. Van Gogh shows us people socializing in this sense: come together in each other’s company to enjoy something in common, part of which is their ‘society’, their enjoyment of enjoying things together.

In fact the street the café fronts on has more people. You can sit on the terrasse and enjoy the passersby, who are in one sense doing their own thing (going to work, strolling) but in another sense participating with you in the life of the town. A town is itself both an association (indulgence in collective life for its utility) and a society: a way of living with, as Hittinger puts it, “a social intention in the strict sense of the term,” which involves mutual enjoyment:

The union itself is loved. (21)

Sitting on this terrasse in Arles you are not confined in a space by the electrified fence of a road streaming with cars (where people boxed-into their ‘vehicles’ are ‘transiting’). It may be a distraction to mention automobiles, but my point is simply that cars turn the streets we see in Van Gogh – which are still social spaces – into channels: structures dedicated to a single function. The space of the town in Van Gogh’s painting is not carved up into instrumental zones (here you enjoy your coffee and conversation, provided you can hear that conversation, there you drive your car); the space in the painting is a whole that is in front of you as a spectacle to be enjoyed.

Van Gogh picked a vantage point to capture the whole theatre. Seated on the terrasse you do not resolutely turn your back on the zone for cars but sit and witness the quiet life of the streets, enjoy the lighted windows of the facing apartments, enjoy your society or fellowship – as Hittinger notes, the Greek word is koinonia. ‘Socializing’, then, is not communicating only; it is voluntary participation in a way of life that you share with others, in which others choose to join you, in which they co-operate with you. So even in this café terrasse, turned as it is on the town, there is a kind of enjoyment of this commonality that is itself a feature of dwelling.

“We dwell where there is a social union with reciprocal action for common ends.”

Russell Hittinger, “The Common Good and its Counterfeits,” Newman Institute Lecture Series (2017)

THE STARS

The whole in Van Gogh’s painting, however, extends further. It is possible that what Van Gogh produced while on site was his still-extant drawing. It is quite a bit easier to manage paper and chalk than a canvas, a box of paints, and turps and brushes. When he wrote to Theo saying that he painted his Starry Night “at night, under a gas-lamp,” he surely means a gas lamp out of doors. Still it is possible that he began the Terrace of a Café with the drawing, which he may have transferred to canvas and then completed on the street.

In any case, he made a notable alteration on the canvas, extending the scene upward to take in the stars above. The whole of the scene in Van Gogh’s painting includes the stars, which we know from his letters held special significance for him. That significance could be a topic of discussion unto itself, which I will not embark on. Certainly there are two marvellous pictures with which to connect it. Commenting on his purchase of the most famous one, the director of the Museum of Modern Art (whom we have encountered before) wrote that Van Gogh’s dynamic “exploding stars”

reveal the unique and overwhelming vision of … a man in ecstatic communion with heavenly forces.

“B.” [presumed to be Alfred H. Barr, Jr.], “Van Gogh’s ‘Starry Night’,”

The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art 9:2 (1941), 3

Does this seem too religious a reading? A proper answer to that question might include these passages from the letters.

That same night I looked out of the window of my room onto the roofs of the houses one sees from there and the tops of the elms, dark against the night sky. Above those roofs, one single star, but a nice, big friendly one. And I thought of us all, and I thought of the years of my life that had already passed, and of our home, and the words and feeling came to me, ‘Keep me from being a son that causeth shame, give me Your blessing, not because I deserve it, but for my Mother’s sake. Thou art Love, beareth all things. Without your constant blessing we can do nothing.’

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 31 May 1876

Commenting on a friend who disliked a painting Van Gogh had made, a “stiff, square house with no charm at all,” Van Gogh expands on why “someone can enjoy doing such an ordinary grocer’s shop.” Nevertheless,

That doesn’t stop me having a tremendous need for, shall I say the word – for religion – so I go outside at night to paint the stars,….

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 29 September 1888

The stars have always been an image of heavenly order, an unchanging order that has allowed one blogger to note that

The positions of the stars in the night sky of Café Terrace at Night is accurate, according to astronomical data.

“Café Terrace at Night, 1888, by Vincent Van Gogh,”

Vincent Van Gogh.org

The heavenly order of the stars overarches the human domain, and draws the lowly creature to look up, as this picture has us do, and contemplate “the whole scheme of the universe,” to borrow a phrase from Rerum Novarum (sec. 21). Van Gogh’s Night Café Terrace is a figure of the whole, from the proto-society of the café terrasse to the celestial order to which it is yoked, by virtue of nature.

I am saying not that Van Gogh illustrates the Catholic teaching on the nature of societies that Hittinger treats in his book (thus its cover) but presents, rather, simple natural things: apparent and intelligible things. Van Gogh has painted the delight in society that underwrites the existence of the café terrasse, the enjoying that is part of what the anonymous townspeople seen in this picture do in such a place, because they are human beings. And he has painted it under, and so in relation to, the arch of the heavens. I am not saying that Van Gogh was conscious of any of this (believed what Leo XIII was only at that moment writing – how could that be?); we are looking at his picture.

As I noted before, the meaning of the work lies in what the work shows us, and it shows us human society in this natural order. I noted that Leo wrote, “Nothing is more useful than to look upon the world as it really is.” The world really does hold these lessons that are to be recognized in it, and it is possible to paint the ingredients of that lesson, together in their true relation, one element naturally higher than the other.

4 | Closing thoughts on this picture of a glorious whole

What does this picture mean – actually mean, we want to add? We can answer this by first asking, What is it that a picture actually says?

This and any picture means what it can say, and saying is also a co-operative activity.

A work of art means what it says, and it will say what it is actually shaped to say, whatever fantasies its maker might have harboured. But this idea of the work’s own statement does not imply what people tend to think: that what is important, then, is that the viewer be equipped to receive what the picture is actually shaped to say. – To put it in another way, I have not been facilitating any such ideal transaction; I have simply been reading Van Gogh’s work, actually reading.

The present moment – the moment at which an actual person comes before the image and looks – is more real than that conception of ideal transaction (the reader given the key that truly unlocks the work). If any perfect matching of onlooker to image is possible, the only way ever to reach it is by mismatch: coming to the work and simply reading as who you are. – Jesus speaks to the entire crowd, not just to whomever has ears to hear. The disciples are among those who do not hear: Jesus indeed speaks to them, they hear what they can, and retain it, and re-hear it later in the light of other experience.

The work will mean what it can say and the listener will hear what he or she can hear, and a great deal of hearing is hearing the harmony of what is true. The work of an interpreter, then – a reader of art – is to say to the one looking at this picture, do you not hear the harmony, do you not hear the chord (this note, and that note, sounding together), and where this is heard this will often be a harmony of truth. Something has become visible that is harmonious with the way you, the onlooker, see the world.

There is a whole in Van Gogh’s picture. “The celestial blues and yellows” with which Van Gogh catches our eye lend their special charm to a whole to which they belong. What Van Gogh achieved in his mature work was a vision of the world – a revelation (and no one reveals anything to himself) – in which the charm of colour harmonies and the charm of the space, the stage-setting, of human existence (a space of cafes and streets with people strolling, where we see the lighted windows of parlours and bedrooms, a place canopied with stars) are united into “the whole scheme of the universe,” or at least a particular glimpse of it. That whole may be contemplated in the spectacle Van Gogh set out in the form of his pictures, which are pictures of a reality that is invisible to ‘realism’. These are pictures that give access to the revelation.

This is what Van Gogh’s later work captures and presents. In that work he does not find his “true means of self-expression” (he is not opened up, so that some inner content could be released); rather he is granted a revelation and is enabled to dwell in the revealed world.

READING, MEANING, & CULTURE

The work of the interpreter is to give access to what is accessible in the work through its resonance with what people (you the reader and also others) have already understood about the world. It makes no difference whether the work is accessible to everyone, and there is no pre-decided package of presuppositions that the right interpretation will cleverly isolate so as to unlock the mechanism. The work of interpreting is fundamentally the task of understanding your own existence, a process to which ‘reading works of art that you come across in life’ belongs. This activity may begin wherever you are standing.

But meaning is not a kind of content; rather it is a kind of event. It is not the endpoint of licensed reading but a phenomenon, in which something is meaningful.

It would seem that there must also be a kind of society of readers who delight in what they can see together: who are united in their common experiences of meaning, obtained by reading. We have already noticed the café-goers who find each other’s company meaningful. More generally, communal meaningfulness is plainly crucial to the three necessary societies noted by Hittinger (the family, the ‘nation’, and the Church). Perhaps (instead of coming up with yet another society, a society of readers sharing the meaningfulness of its way of reading) the right thing is to see that the essential societies share experiences of meaning proper to each. Yet, at the same time, there may be some unification of these, drawn together into the one task of making sense of things as a human being (not as a family member or as a Christian). Might there be a distinctive way of reading spun from all these roles (in which, say, the epiphany of a spouse is used to understand the Church, etc.)?

A culture might be a society of readers who share the meaning found by reading (the meaningfulness that is the resonance of truth). That might be the meaning interpreted for them (as pastors interpret Scripture), a work of dissemination not just absorption into private experience. A culture might also be a society of readers who use one such epiphany to discover another, in that way becoming an instrument of meaningful and glorious vision for the many.

Artist

Vincent Van Gogh (1853–1890)

Date

Circa 16 September 1888

Collection

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Titled there

Terrace of a Café at Night (Place du Forum)

Medium

Oil on canvas

Dimensions

80.7 × 65.3 cm | 31.8 x 25.7 in

. c