Contemplation; Unequals made one in love | Dalou’s Boulonnaise nursing her child

In this essay,

• A QUESTION IS ASKED ABOUT ART & WHAT (SOME) ARTISTS ARE LOOKING FOR

• THEN A NEGLECTED ARTIST IS INTRODUCED, WITH A LOOK AT HOW HE BEGAN HIS CAREER

• FINALLY, THE PATH IS FOLLOWED TO A REMARKABLE WORK THAT IS REVELATORY OF THE CHARACTER OF LOVE, WITH AN EXPLORATION OF ITS HIGHER DIMENSION

• WITH A CLOSING OBSERVATION ON BLINDNESS

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | Art & not art

An artist need not search. By one conception of the artist’s business, an artist picks up the tools of art and produces something to look at (that product: art). Or, a variant conception: an artist is one who makes what his society finds attractive, beautiful, moving. – But there are artists who reject both such conceptions. This is the artist who, when he has done that – made what counts as art by either of these conceptions (producing work with artistic qualities, gathering an audience via these qualities) – he nevertheless rejects this art as not at all the thing he is after. It does not succeed as art: it is rather a failure: it is not art, which is the thing that he was struggling to bring before the eyes of people.

This kind of artist is a searcher. He is trying to find, by way of the choices he makes, a passage to something, to that thing that is the aim of art, of art as he sees it. Jules Dalou was an artist of this sort.

This kind of artist is a searcher. He is trying to find, by way of the choices he makes, a passage to something, to that thing that is the aim of art, of art as he sees it. Jules Dalou was an artist of this sort.

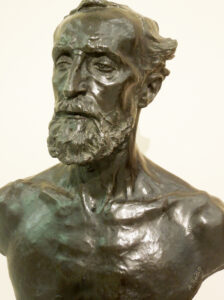

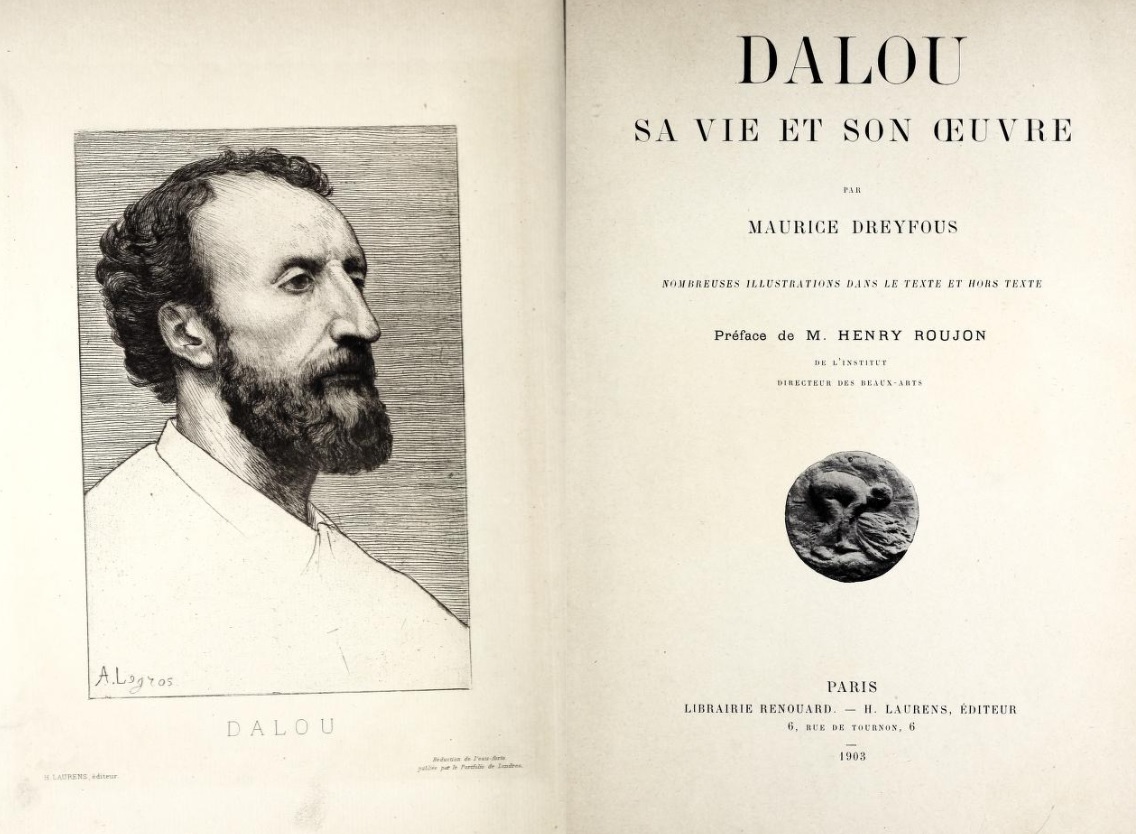

Though largely forgotten today (his name is missing from standard dictionaries of art) Dalou was a sculptor well known in his time. In France, where he was born, he was made Commander of the Légion d’Honneur, accorded the same rank given to Rodin, his contemporary and friend. (Born about a year apart, Dalou and Rodin attended the same art school together, and Rodin would make a portrait bust of Dalou for the Salon of 1884.) It was Dalou whom France commissioned to create the enormous monument (involving 42 tons of bronze and on which Dalou worked for twenty years) celebrating the Triumph of the Republic, for the Place de la Nation in Paris. During the earlier part of his career, the part that concerns us, this state recognition was inconceivable to Dalou, owing to crimes that got him condemned to a life of penal servitude.

BEGINNINGS

Aimé-Jules Dalou was born in Paris on the last day of the year 1838 to a glovemaker and his wife, the youngest of three children. French Protestants, both parents were also vocal republicans: committed to the mode of government set up during the Revolution of 1789 (establishing France’s First Republic in 1792), but a government since overthrown first by dictatorship (Napoleon) and then by a return of the monarchy (the Bourbon Restoration). I echo professor of history Sarah Horowitz in saying that however divided we are today, in our basic understanding of things and in the deepest commitments, we are – and I might suggest paradoxically – united in our views of government. Canadian, American, or British, committed however we are, we do not appear to question either the equation of good government with democracy or the particular formula (parliamentary, bi-cameral, or whatever form is ours) that delivers that good government. This was not at all the case in nineteenth-century France.

In 1830 France underwent a second rebellion, the July Revolution, with more spilt blood and another change of governmental structure – a re-revolution captured in Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, painted that same year and foregrounded with corpses. France would suffer a third revolution the year Dalou turned ten, in 1848 – one surely welcomed by Dalou’s parents as it established the Second Republic.

In 1830 France underwent a second rebellion, the July Revolution, with more spilt blood and another change of governmental structure – a re-revolution captured in Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, painted that same year and foregrounded with corpses. France would suffer a third revolution the year Dalou turned ten, in 1848 – one surely welcomed by Dalou’s parents as it established the Second Republic.

But in four years this republic too collapsed, as the figure at the helm was – rather like Canada’s Justin Trudeau – a complete unknown with a winning pedigree. (Louis Napoleon was Napoleon’s nephew and was handed this power, says Prof. Horowitz, “just because of his famous name”.) – To pause momentarily, it is worth reflecting that, if the problem is simply to unite a divided people (to find something on which people who are ‘all over the place’ can agree, so that the people, equated with a majority, can declare its will) the answer to this problem might indeed be crazy hope inspired by fame. Why not lunatic dreams pinned on name recognition? So a better basis of unity might be the thing that makes unity count. – It could not really have come as a surprise when the Napoleonic nephew decided that … he could also be emperor, and then turned the Second Republic into the Second Empire.

It was in 1852, the first year of this Empire, that Dalou, aged thirteen, entered art school. The time had come for him to make his way; the five francs a day earned by his father had to feed five people.

Classes at the Petite Ecole (which began at 6 a.m.) greatly focused on the direct observation of nature. After a year Dalou was thought fit by his teacher to enrol at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the art school of France, but Dalou soon became disenchanted with the instruction there, which paid much more attention to exemplary art (when decades later the school praised him he rebuffed the praise, still embittered by memories). He did not quit, however, but persevered long enough to take advantage of the studio, materials, and life classes, yet he did not complete the normal course of instruction.

After this (young and free) he drifted somewhat, making decorative ornaments for the new mansions of Second-Empire Paris, even working for a taxidermist, sculpting the posed forms on which the animal skins were mounted. Encouraged by pals from the Petite Ecole he sculpted an entry for the Salon, the annual exhibition of the Academy that ran the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (his friends scraping up the money to have his work cast in plaster to meet entry requirements). And then in 1866, in his late twenties, Dalou married, and in the same year re-enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

It appears that he had now determined to make a real career as a sculptor. Within a year he had a daughter, who was born premature and permanently handicapped; she would require constant family care throughout her life. He had begun to compete for the nation’s pre-eminent art award, the annual Prix de Rome, which would make his career, but in four years of trying he always fell short. It might be said that this plan of career, driven by the immediate need to provide for a family – which is always a plan to contend with the forces and obstacles ranged against success by the always imperfect way things are, the aim at a goal that was not just making a living – had put him onto a path of conflict. It was a path wisely chosen. If the goal is worthy (including such results as the one we will examine), there will be a dragon.

POLITICS & ART

Dalou was thirty-two when, during the Franco-Prussian War (triggered in 1870 by Prussia to exploit the weakness of the ‘emperor’ and seize the German-speaking corner of France), Napoleon III was captured by the enemy, setting off still another revolution in France. Paris was now under siege by the Prussian army and, in this moment of uncertainty (uncertainty-counted-as-opportunity) two rival governments were created to rule over France: one in Versailles (led by an opponent of the Second Empire) and one in Paris, led by the people (who mistrusted the Versailles leadership, judged too reactionary). This second government was the Commune de Paris, named after a governing body of the French Revolution; it is a term not unrelated to Communism. The Communards were a mix of republicans, socialists, anarchists, and Marxists, among whom was Dalou.

To be brief – as brief as I can in sketching Dalou’s situation, the setting of this period of searching that concerns us (searching for what? and why search?) – the world in which Dalou had embarked to become an artist was in serious turmoil; Dalou’s biographer, writing in 1903, calls it a “temps bizarre”.

Maurice Dreyfous, Jules Dalou, sa vie et son oeuvre

(Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1903), 45

In these bizarre times this son of a glovemaker suddenly found himself in charge of the Louvre. The events are as follows.

The Paris Commune – in effect the world’s first practical experiment in socialist or proletariat rule – came about when on March 18, 1871 (months and days are relevant as the events unfolded rapidly) the National Guard took control of the city (which is why photos of Communards often show uniformed men). Days later the Commune

was elected, its members immediately declaring that workers could become the managers of their workshops. Day by day new ways of running the country were worked out by ordinary labourers (abolishing the death penalty and military conscription, separating the state from the Catholic Church, etc.).

In all that was in play, art was not forgotten.

On April 15th some four hundred painters and sculptors, engravers and cartoonists, under the painter Gustave Courbet met (“with the permission of the Commune”) in the lecture hall of the School of Medicine to elaborate a plan for, as this group soon explained, “the inauguration of communal wealth” in the sector of art. The meeting established a Federation of Artists that began by working out its duties, which were immediately published in a statement signed by Federation members, a document bearing the name “Dalou, Jules”.

In all of the duties specified it is truly difficult to find any new activity not already managed by the state Académie des beaux-arts or some other department of government: the Federation would organize exhibitions, run schools, publish (“on the aesthetics, history, and philosophy of art”), look after monuments and artworks “not belonging to private individuals” and “place these at the disposal of the public in order to encourage studies and satisfy the curiosity of visitors”. (The Louvre, for instance, had already been turned, during the Revolution in 1791, from a royal palace into a public museum.) The new element in the plan was the handing of all this activity to the people, and the apparent elimination of the involvement of the upper classes. Where the document announces

the free expansion of art, free from all governmental supervision

Proclamation of the Federation of Paris Artists

under the Communal Republic (1871),

trans. Jeff Skinner, Red Wedge (15 April 2016)

‘government’ here must be read as ‘the class that has thus far controlled everything’, as “the Communal Republic” in whose name these artists were speaking was indeed a government.

One month after this meeting Dalou was named one of the three curators charged to protect the Louvre’s collection, but he held this post for only a week as on May 22nd the rival government in Versailles attacked Paris, beginning the Semaine sanglante (Week of Bloodshed).  During this dark week of civil war the Communards took hostages (and as they were being defeated killed them) and burned down the Palace of Justice, while the attack that crushed the Commune, and then the reprisals and executions, claimed thousands upon thousands of lives. Dalou, sure of his arrest, left the country with his wife and daughter. For usurping state functions at the Louvre he was, indeed, condemned in absentia to a life of hard labour.

During this dark week of civil war the Communards took hostages (and as they were being defeated killed them) and burned down the Palace of Justice, while the attack that crushed the Commune, and then the reprisals and executions, claimed thousands upon thousands of lives. Dalou, sure of his arrest, left the country with his wife and daughter. For usurping state functions at the Louvre he was, indeed, condemned in absentia to a life of hard labour.

2 | Searching & destroying

Knowing scarcely any English, Dalou fled to England to stay with Alphonse Legros, a fellow student from the Petite Ecole who had married an Englishwoman and begun a career in London.

In these unsettled years, which one might think unconducive to finding one’s way, what kind of work did Dalou produce? After two months with his friend Legros he moved his family into a two-room flat and began work on a statuette in terracotta (fired clay) of a young woman, in a cloak apparently characteristic of Boulogne, carrying her prayer book and palm fronds. Submitted to the Royal Academy exhibition of 1872 under the title Jour des Rameaux à Boulogne (Palm Sunday at Boulogne), the work was not only accepted  but bought by an ardent English socialist to whom Dalou was introduced by Legros.

but bought by an ardent English socialist to whom Dalou was introduced by Legros.

In light of the class consciousness of the Commune it is worth noting Dalou’s report, in 1873, that

the English receive us with open arms, and in the richest class, nobility or bourgeoisie. We are seen as political refugees, … [and] I am received in some of the richest houses and of the most ancient nobility.

Dalou, letter of 9 January 1873;

Dreyfous, 51

On the subject matter of this first work Dalou completed in England it is impossible not to see the influence of Legros, who was famously devoted not just to Christian subject matter but (as scholar Elizabeth Prettejohn puts it) “subject matter involving religious observance”. Indeed, Prettejohn ably makes the case that that choice has made Legros virtually invisible to art historians today (he is even more “inconspicuous in our art history books” than Dalou), an absence from the record that she terms “The Scandal of M. Alphonse Legros”.

As for Dalou himself, what he saw in Christianity is quite unclear. Later in life he wrote,

The thought that presides over Egyptian art, that of Greek art as well as Christian art, all that is erased for us, living as we do in an age of skepticism and transition,….

Dalou, letter of January 1896; Dreyfous, 18

It certainly appears as if Dalou and Legros were working the same vein of subject matter. Legros had done peasant subjects for some years, Dalou in London had just produced his first. Around the time of Dalou’s Palm Sunday statue Legros did an etching of possibly the same girl of Boulogne seated in church, a subject also sculpted around this time by Dalou (known today only in a photograph). Note Dalou’s signature on the photo of his sculpture; that artists would sell (and sign) photographs of their works as another means of giving art to the people. The Federation of Artists had made just such a commitment, noting that

Through popular reproduction of masterpieces, and through intelligent and edifying images that can be spread in profusion and displayed in the town halls of the most humble villages in France, the committee will work towards our regeneration [and] the inauguration of communal wealth,….

Proclamation of the

Federation of Paris Artists

DESTRUCTION & DISCOVERY

In this same period Dalou is known to have destroyed clay sculptures that he had entirely finished, though evidently not to his satisfaction.

I have just lost three months working on a thing that I flung in the bucket, only, for still more months, to take another false path on some other thing that has to be entirely redone;….

Letter, 18 May 1874; Dreyfous, 55

His biographer writes,

The works of Dalou, completed but then ‘dumped in the pail’, are so numerous that … it is scarcely possible to list them.

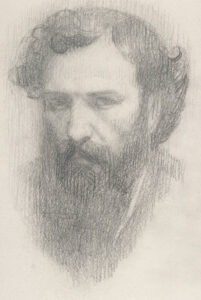

This was work that had impressed people who saw it. One such work was a very large sculpture group on the subject of Hercules attempting to suckle at Juno’s breast, to drink the milk that gave Jupiter’s children eternal life – attempting because Hercules was the illegitimate son of Jupiter, Juno’s husband, and Juno (protectress of legitimately married women) had no intention of granting this boon to the fruit of her husband’s betrayal. Little remains of this project but a clay sketch and a rough  drawing of Juno appearing to cover her breast (below). The account of this work in Dalou’s biography concludes,

drawing of Juno appearing to cover her breast (below). The account of this work in Dalou’s biography concludes,

This group, measuring almost two metres in height, was completed and ready for delivery to the cast-maker when Dalou dumped it in the tub, leaving not a single element intact. Mr. Lantéri, who had assisted Dalou with the execution of certain details, and Mr. Legros, who had seen it in its completed state, affirm that it was of an incomparable beauty.

What did Dalou want? Dreyfous, his biographer, answers by turning to what may have been the next work Dalou created, which was not destroyed.

If you compare … the [pencil sketch] of the Juno and the figure of the Paysanne [i.e., a work exhibited under that name, shown below], you grasp their quasi-identity; but, examining the differences between these two works, you discover the actual motive for Dalou’s severity toward his Juno. As beautiful as she may be, she was only a figure of convention. Dalou … felt vaguely that she would never possess those beautiful qualities of sincerity, fidelity, and truth that were the very essence of … his personality as an artist. At this moment he

had been searching in vain for his path…. How he found the solution to this problem and from where it came to him, this we know today.

Dreyfous is referring to a photograph of the newer work that was among Dalou’s personal effects,

the only photograph of the works of Dalou to which he had accorded … the honour of a modest frame, … on which you read this dedication: “To she who has inspired this statue. J. Dalou.”

Dreyfous, 60

‘THE LIFE-GIVING IDEA’ IN ‘THE EXAMPLES FURNISHED BY LIFE ITSELF’

It was Dalou’s wife, Irma Vuillier, then in her twenties, who, writes Dreyfous,

had inspired the living idea of the [Palm Sunday figure], she who had made her husband sense that, in sculpture as in all things, the most direct route is always the best, that to express the poetry of the woman nourishing the child by the gift of her entire being the most certain way, here as elsewhere, lies in naive and direct sincerity. What is the sense of turning to Juno … when the first woman who comes along with a child at her breast will revive in you the feeling that is engendered only by masterpieces. It is the duty of the artist to choose, among all the available examples furnished by life itself, the one that, by its form, will symbolize most profoundly the life-giving idea [l’idée générique] in his work…. It will be up to him to bring out this form in all its perfection … and to achieve this unity of the Beautiful and the True that is the final cause of all the Arts.

Dreyfous, 60–61

Of the statues made by Praxiteles and Pheidias, Dreyfous remarks – all statues of the human body – there is nothing of antiquity about them. When they were made they were contemporary. These sculptors

worked from the life that they found around them. They were: contemporary, therefore alive. And that is why their work has remained alive.

Pheidias and Praxiteles were not antiques. They became antiques.

It is for this reason, concludes Dreyfous, that

between the mythological Juno settled on her cloud and the common girl of the French countryside, sitting on her wicker basket, it is the peasant woman, not the goddess, who has the aura of ancient sculpture.

Dreyfous, 61–62

When this fully life-sized figure of a French peasant girl nursing her child was shown at the Royal Academy in 1873 its success was unparallelled.

The public crushed in to see it, the wealthiest art lovers lined up to buy it at any price, the Duke of Westminster offered any sum of money

Dreyfous, 61–62

(an opportunity missed by Dalou, who had already promised the work to another collector for less).

‘POPULARITY’

The popularity of this statue surpassed the reception of Dalou’s first depiction of a nursing mother, a statue (now lost but known from a photograph) that was also life-sized and that he had shown at the Royal Academy the previous year. That is, for two years running Dalou had submitted to the Academy exhibition statues of a nursing mother, first a bourgeoise in a rocking chair then a peasant girl. Indeed he carried on working with this subject, producing eight different versions by 1877.

The popularity of this statue surpassed the reception of Dalou’s first depiction of a nursing mother, a statue (now lost but known from a photograph) that was also life-sized and that he had shown at the Royal Academy the previous year. That is, for two years running Dalou had submitted to the Academy exhibition statues of a nursing mother, first a bourgeoise in a rocking chair then a peasant girl. Indeed he carried on working with this subject, producing eight different versions by 1877.

Because this subject was popular? – But the question is surely, what does popularity actually mean? Does a man of republican principles treat popularity as a slur? That a work of art appeals ‘to the people’ is a defect of that work only to that sort of person who thinks the people incapable of grasping that quality of truth and beauty that art of genuine value possesses. It is noteworthy that the ‘manifesto’ of the Federation of Artists (people we would all call leftists) spoke of “masterpieces” and of “edifying images” – the latter being the language of St. Paul for building people up into a healthy and vital condition. These radicals went on to affirm that such images would have this effect in “the most humble villages in France”. (Leftists now scoff at the very idea of a ‘masterpiece’.)

Further, under its mandate for education this art agency of the Commune had proposed to “designate the subjects among which a higher spirit is revealed” – which is to say, it asserted that there is a decided “higher spirit” – there is no hint that this is in the eye of the beholder – that we, collectively, should care about, this being art’s primary importance. It is also implied that this spiritual quantity is not ‘laying about in the open fully known to everyone’ but is something under a veil in the lives of men, because it is to be “revealed”.

Proclamation of the Federation of Paris Artists

Were it suggested that this is to read too much into a mere phrase from a document of quite few words I would suggest – showing more charity – that the authors knew exactly what they were talking about and knew how to how to say it. Courbet at al. have the air of comprehending their subject.

Later in life Dalou wrote,

To be lasting, a work of art must be strong in conception and beautifully executed. The conception engages the crowd, but the execution addresses only those who know what is what, and such people are rare. The idea [La pensée] fades away in taking shape but if the piece is beautiful it remains, of necessity.

Dalou, letter of January 1896; Dreyfous, 18

In this he marks a certain division between the crowd (“la foule”) and those who see (“s’y connaissent”) … see something that, he suggests, is there to be seen, that “remains” within the work, but that the crowd does not see.

We could interpret this quality that he calls “the execution” (it is the same word in French) as simply the manner of handling the clay, but surely people are widely capable of appreciating skilled use of a material; it is far more likely that he is referring to something entirely different.

Does this division that Dalou has marked simply wind up repeating that prejudice of the elite (disdain for the sensitivity of ordinary people) that Dalou had once condemned; is that the contrast expressed here? Or is Dalou indicating what he as an artist was seeking, hinting at his own purpose in art, … his reason for dumping finished work in the tub?

3 | La boulonnaise

When in 1876 Dalou took up the subject of a nursing mother yet again, a crass reading of his decision would be, the subject was a crowd pleaser. The same might be said of choosing to return to the peasant in Boulonnaise costume: notes a curator at the Dahesh Museum of Art in New York,

women from Boulogne [was] a theme made popular by the paintings of Alphonse Legros

“The Woman of Boulogne,” Dahesh Museum of Art

– ‘popularity’ once again. Of this work Dalou’s biographer writes, with a clear note of displeasure,

He continued his work almost mechanically. And, since the Boulonnaises appealed to the public, he began to make Boulonnaises

Dreyfous, 79

– the bugbear of ‘public appeal’. Dreyfous here makes no allowance for the possibility that the subject and what is distinct about the ‘Boulonnaise’ figure (who is characterized in this work by little else than the enveloping mantle of the regional costume) would both afford Dalou the opportunity to achieve something out of the ordinary.

The work that Dalou began was another life-sized terracotta, completed in 1876 and publicly exhibited for the first and last time at the Royal Academy in 1877, under  the title “Une Boulonnaise allaitant son enfant” (A Boulonnaise nursing her child). It had again been purchased directly from the artist prior to the exhibition, this time by an aristocratic Irish family and then displayed in the family house near Westport, County Mayo – for the next one hundred and forty years, at which point it was purchased at auction by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

the title “Une Boulonnaise allaitant son enfant” (A Boulonnaise nursing her child). It had again been purchased directly from the artist prior to the exhibition, this time by an aristocratic Irish family and then displayed in the family house near Westport, County Mayo – for the next one hundred and forty years, at which point it was purchased at auction by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

Katherine Stauble, “Your Collection: Recent European Arrivals at the NGC,”

Magazine (25 August 2015)

The statue is set on an octagonal wooden pedestal, designed by the artist, that raises the pair above you: a seated mother and her child both wrapped in her voluminous cloak. The mother is turned slightly at the waist and so ‘faces’ more than one direction; there is no ‘central view’. When the statue is looked at from successive positions, facing each facet of the pedestal, the outline of the whole takes a notably different shape. The volumes of the cloak are markedly varied and engaging, as is especially notable by comparing the robe in the early study that  Dalou made in planning the group. Dreyfous notes the appearance, from just one perspective, of “a cascade of loose, heavy, supple folds rounded at mid-fall.” To say that, compared to the Paysanne of the year before, this conception of a cloaked mother and child is simple would betray obliviousness to all that unfolds when we take in the work instead of just casting it a glance.

Dalou made in planning the group. Dreyfous notes the appearance, from just one perspective, of “a cascade of loose, heavy, supple folds rounded at mid-fall.” To say that, compared to the Paysanne of the year before, this conception of a cloaked mother and child is simple would betray obliviousness to all that unfolds when we take in the work instead of just casting it a glance.

The mother is seated on a rock, but actually something too lacking in detail to signal anything but a seat – quite different, then, from the terracotta Paysanne sitting on her upturned wicker basket, which sounds another note of the peasant theme (falling in with her clogs and basket of carrots). There is no such theme in the Boulonnaise, whose chief impression is the ‘monumentality’, so to speak, of the mother and child, the cloak being a natural thing that at the same time functions as a kind of symphonic form leading us to the climax of the work: the strikingly vertical relation of the mother and her child.

Standing before one particular facet of the pier we see the head of the mother turned down toward her child, a virtual straight line running between their heads (suggested by or emphasized by the long bridge of the mother’s nose). Where the Paysanne had shown us a moment in time – a lively figure arrested in mid-motion to nurse what looks to be a moving child – this ‘hierarchic geometry’ of the Boulonnaise, who is not moving at all but entirely still, seems to take us onto another plane of life altogether, even outside of time.

Standing before one particular facet of the pier we see the head of the mother turned down toward her child, a virtual straight line running between their heads (suggested by or emphasized by the long bridge of the mother’s nose). Where the Paysanne had shown us a moment in time – a lively figure arrested in mid-motion to nurse what looks to be a moving child – this ‘hierarchic geometry’ of the Boulonnaise, who is not moving at all but entirely still, seems to take us onto another plane of life altogether, even outside of time.

This reveals something about art, or form, or something that we have been inquiring about when asking what the artist is after. ‘Hierarchic geometry’ does not mean anything verbally. You could not use these words all by themselves and convey any clear meaning. But they can be used to grasp, in a crude but functional way, what we are seeing in this instance of communication, … where the work has the initiative and it does the speaking (saying what it does).

From this particular angle we grasp the relation between the two figures, the mother above and the child below (extremely reduced to its round head). Seen from another angle a few steps to the right, the mother’s face is more fully visible, with the child’s still hidden (yet the round crown of its head is prominent). Again from this aspect there is no visible action whatever, other than this silent looking. Taking a further  step you see the group from the rear (the cloak, the hood spread out on the mother’s shoulders) and when you come around again to the front you now see the action of the mother bringing the nipple to her baby’s mouth. Yet in the ensemble of the whole this action is muted and recessive – again, quite unlike the Paysanne, where Dalou has created a genuine sense of motion, in the baby’s outthrust foot, the young mother appearing to shift, balancing the baby on her knee while leaning in to feed him). “The conception” or the “thought” in the two works (to use Dalou’s terms) is entirely different.

step you see the group from the rear (the cloak, the hood spread out on the mother’s shoulders) and when you come around again to the front you now see the action of the mother bringing the nipple to her baby’s mouth. Yet in the ensemble of the whole this action is muted and recessive – again, quite unlike the Paysanne, where Dalou has created a genuine sense of motion, in the baby’s outthrust foot, the young mother appearing to shift, balancing the baby on her knee while leaning in to feed him). “The conception” or the “thought” in the two works (to use Dalou’s terms) is entirely different.

THE VEIL OF LIFE & WHAT IS BENEATH

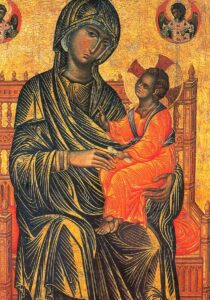

The Boulonnaise has realistically rendered details, delicately modelled in the clay: the complex folds of the cloak, the finely detailed clasp attaching the mantle, the quilting of the bonnet, the shoelaces of the mother’s shoe, the part in her hair, with a single straying wisp. But this overall blanket of realism does not chain the image to temporality. People explaining Byzantine icons will sometimes say that the  geometrization (etc.) given to the saints, the refusal of ‘Western’ modelling, means that the artist is depicting more than the visible body, more than temporality, and this claim is not false. But Mary, the Theotokos, was more than a body in time even while she had a body in time, while she nursed Jesus in Bethlehem in much the way we see this young mother do here, sitting on a rock, dressed in the costume of a particular people. The Byzantines’ golden striations and avoidance of shading are simply chosen artistic means of showing the fuller reality that transcends the realm of particular and mundane details, and there are other such means.

geometrization (etc.) given to the saints, the refusal of ‘Western’ modelling, means that the artist is depicting more than the visible body, more than temporality, and this claim is not false. But Mary, the Theotokos, was more than a body in time even while she had a body in time, while she nursed Jesus in Bethlehem in much the way we see this young mother do here, sitting on a rock, dressed in the costume of a particular people. The Byzantines’ golden striations and avoidance of shading are simply chosen artistic means of showing the fuller reality that transcends the realm of particular and mundane details, and there are other such means.

Dalou, who was perhaps not even a believer, shows us another way here.

The mother’s cloak encloses her and her child. Not long ago on social media a young mother posted the comment,

A peculiar thing about motherhood is that when I feel it’s a little cold, my first instinct is to put the blanket on the baby rather than to grab a sweater for myself. As if my senses exist to provide for my baby first and then myself.

This is practical evidence of the ‘oneness’ of mother and child. We might imagine, with the obtuseness suited to a veiled reality, that a mother and her child are more correctly seen as two separate people, but the evidence just ‘put before our eyes’ by this mother, observing and learning from her own behaviour, says otherwise. It would do justice to her experience to say to her,

Yes, exactly, you find that ‘you’ are cold and then your actions show you the meaning of this ‘you’. Love unites.

The mother and the child are altogether different, in reality and in Dalou’s sculpture, which shows us … one higher than the other, … one with open eyes and one with  closed, … one attentive to the other and the other oblivious to, not even conscious of, the mother, not knowing her – two beings in two dramatically different states, but yet the two are one in love, the love of the mother. Dalou, with this enveloping cloak, has produced a form that shows this union: the mother and child drawn together into a union of, for now, one-sided love.

closed, … one attentive to the other and the other oblivious to, not even conscious of, the mother, not knowing her – two beings in two dramatically different states, but yet the two are one in love, the love of the mother. Dalou, with this enveloping cloak, has produced a form that shows this union: the mother and child drawn together into a union of, for now, one-sided love.

The cloak the mother wears is also shown opened, and opened in an intriguing manner: the infant appears to emerge out of the woman’s body. Commenting on the “divinely human legend” of Juno, who as a mother was “twice creator of her children” (giving them birth and then immortality, both through her body), Dalou’s biographer mentioned “the supreme mystery of life, the work of love and light.” In Dalou’s sculpture we have the supreme mystery of love, love via body and soul.

In the centre of the mother’s figure, around her heart, the opening of the cloak is a kind of emblem of her body: first, a far more beautiful evocation of the source, the Origine du monde, than that infamously painted by Courbet; in this opening are, further, the life-giving breasts – but above the body is the consciousness, the steadily engaged awareness that surveys the child, watches him in a state of speechless love – contemplates the child. This is a perfect image of contemplation, which involves silent adoration. The mouth of the mother is closed. Whereas a faint smile plays over the lips of the Paysanne the mother here is not expressing anything; she is taking in.

In the centre of the mother’s figure, around her heart, the opening of the cloak is a kind of emblem of her body: first, a far more beautiful evocation of the source, the Origine du monde, than that infamously painted by Courbet; in this opening are, further, the life-giving breasts – but above the body is the consciousness, the steadily engaged awareness that surveys the child, watches him in a state of speechless love – contemplates the child. This is a perfect image of contemplation, which involves silent adoration. The mouth of the mother is closed. Whereas a faint smile plays over the lips of the Paysanne the mother here is not expressing anything; she is taking in.

Body and soul, I said, but we see the soul here in the form of mind. When we think of the ‘mind’ we are always influenced, regrettably, by what has been done to our understanding of the spiritual component of our being. In the face of the mother we are seeing a mind, which sees and loves. The mother is gazing at this child that she knows she has created, a new being that she has already, consciously and as an act of will, risked her life for. Theodore Roosevelt remarked that,

The birthpangs make all men the debtors of all women,

Ruskin, The Art of England, 261

but he also said that all women who give birth are heroes because they

walked through the valley of the shadow to bring into life the babies they love.

Theodore Roosevelt, The Foes of Our Own Household (1917), 271;

cited in Allan Carlson, The ‘American Way’: Family & Community in the Shaping

of the American Identity (Wilmington, Del.: ISI Books, 2003), ch. 1

The pregnant woman embracing life knows what she is risking, and risks it – a very great risk in the nineteenth century, and not even now reduced to nothing. The “supreme mystery of life” is also the mystery of love. In the face of this young woman you see the quiet contemplating mind of the mother who knows, in the infant she sees, the point of what has happened to her; she sees it via love.

It is not an expressive or an exuberant love but a love at complete rest, a contemplative, comprehending love. A gift of life and love “by the gift of her entire being.”

OTHER DIMENSIONS OF SIGNIFICANCE

It is impossible to make these observations without, in the mind’s eye, recollecting medieval and Renaissance images of the adoration of Christ, Mary kneeling in her  blue robe, bent over her impossibly conceived child. One expects that Dalou was surely sensible to this parallel: to the way his statue on its pedestal echoes Virgin and Child images on plinths in the aisles of churches. But if we are seeing any image of Mary here it is an image of Mary simply as a mother: that is, the human phenomenon of natural adoration, of a love that is contemplative – which is to say, a love that breaks through to eternity, shows itself to us at its actual scale, as the love that contemplates.

blue robe, bent over her impossibly conceived child. One expects that Dalou was surely sensible to this parallel: to the way his statue on its pedestal echoes Virgin and Child images on plinths in the aisles of churches. But if we are seeing any image of Mary here it is an image of Mary simply as a mother: that is, the human phenomenon of natural adoration, of a love that is contemplative – which is to say, a love that breaks through to eternity, shows itself to us at its actual scale, as the love that contemplates.

A love that is all-consuming (so that one would willingly die for the loved one), that is sufficient and riveting; a love offered by body and soul, that is knowing, aware of something in the infant – what? – that justifies this love. What Dalou’s statue reveals is the transcendent character of this fact of human experience, of what is put into human nature.

And it is part of the character that is revealed here – the vertical axis – that the love of a mother is the opposite of a love between equals.

And it is part of the character that is revealed here – the vertical axis – that the love of a mother is the opposite of a love between equals.

In showing us, as it does, the inequality of the two become one (the superiority of the seeing one over the one who is oblivious) the Boulonnaise cannot fail but prompt another kind of reflection altogether, on the relation of God to man. It does so even if Dalou had at this point ceased to be a Christian or was ever conscious of this, simply by virtue of its form.

It is the superior and conscious figure who looks down on the unconscious and dependent one. The lower creature, who is doing so little and is itself so much a nothing (lacks so much, is so little developed), arrests the attention of the being who has created. This is a mystery of love, because it is an incomprehensible phenomenon. What is it that the seeing one loves?

The love of a nothing – a nothing by some measure, by the standard that a veiled world inspires (valuing powers, capacities, independence) – is not the love of a nothing: of this, surely, we are certain in looking at this work. Something in the weak one calls out this love, but the sculpture surely assures us that this is so, by the experience of our own families, but it does not tell us what it is. That something, we might say, cannot itself be depicted, or even named, yet we can depict the one who has it.

Human beings simply cannot fathom the nature of this something that in man is loved by God, any more than this infant can understand the love its mother feels for it – but that it is loved is sealed on it by the mother, body and soul. The fact of the love wipes away the questions, and creates a bond, the magnetism that draws the child to his mother and makes him cling to her skirts.

THOSE WHO DO NOT KNOW – OR, TASTE, A REFLECTION OF VISION

Dalou spoke of those who know what is what when approaching a work of enduring significance, who are rare. His point had no connection with class.

His biographer, Maurice Dreyfous, illustrates what Dalou was talking about in his dismissive remarks on the Boulonnaise, which is in fact a work of extraordinary achievement.

It is assuredly, as a whole, a very fine piece of sculpture, and of the most beautiful colouring, but it lacks that beautiful sincerity, that ancient simplicity, which is the mark of masterpieces. The elongated oval of the woman’s face is of the sweetest kind, but it remains the face of an artist’s model and not that of a girl from our French coasts. Not in the eyes she lowers toward the child, not in the closed lips, nor in her overall movement, do we feel the entire gift of self or the scent of maternal tenderness that constitute the unforgettable beauty of the Paysanne. Out of envy or jealousy prompted by any comparison between the two works, a man might easily go to extremes and say that the Paysanne is the ideal personification of maternal love while the Boulonnaise is scarcely more than a ‘Nanny on the spot’.

Dreyfous, 79

The streak of bile in this defense of the honour of the Paysanne comes out of the blue in Dalou’s biography – no doubt someone had scandalized Dreyfous by ranking the Boulonnaise higher, but what explains it? A person’s taste, it could be said, is a kind of condensation of everything that matters to him, and in ‘everything that matters’ there is a great deal of energy, positive and negative.

It is not that the Paysanne is defective; there is nothing missing or poor in its “conception”; it is not a work of saccharine sentimentality but a work of real delicacy and tenderness. But it simply does not venture into the territory of the Boulonnaise: it does not contain the forms and the articulation of elements that I have commented on here and that are conduits of something high above ‘charm’. If the Paysanne is “the ideal personification of maternal love” then maternal love is love marked by tenderness (as that is what we see in this work), but Dalou went on to encounter more. If the face of the Boulonnaise lacks emotion that is because the category of emotion has been confused by Dreyfous with ‘expression’ (the broadcasting of experienced feelings), and that this face is not French enough (!) signals a bondage to preferences that is an actual form of blindness. It is because Dreyfous sees no animation, no local colour, in the face of the mother that he counts it blank.

A curator at the National Gallery of Canada displays a better quality of vision in saying that in the Boulonnaise

It is a noble-faced figure [that we see], a classical woman, her features reminiscent of Italian Renaissance paintings;….

Anabelle Kienle Ponka, cited by Katherine Stauble, “Your Collection:

Recent European Arrivals at the NGC,” Magazine (25 August 2015)

Indeed, this figure by Dalou is unique in being reminiscent of French Renaissance faces like those sculpted by Michel Colombe, when portraying transcendent virtues.

Indeed, this figure by Dalou is unique in being reminiscent of French Renaissance faces like those sculpted by Michel Colombe, when portraying transcendent virtues.

In sum, when Dreyfous remarks that

The success of this statue at the 1877 exhibition of the Royal Academy was quite spirited (though incomparable to that of the Paysanne),

he tells us that some things are seen (because people are equipped to see them by their grasp of reality, their freedom to see), while other things are utterly invisible, not even guessed at, though the two people are looking at one and the same work of art. When we are told something about art, taught about it, we do not know from which kind of judgement the teaching is coming.

[]

Two years later in 1879, amnesty was granted to supporters of the Commune and Dalou returned to Paris. Writes art historian John Hunisak,

Never again would Dalou send an intimate theme to a public exhibition. From [then] on, public monuments absorbed the greatest proportion of his creative energies.

Indeed, he left England already holding the commission for the Triumph of the Republic. On this Hunisak remarked,

With this work, unveiled in November 1899, Dalou’s highest aspirations as an artist were realized.

John M. Hunisak, “Jules Dalou: The Private Side,”

Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, 2:56 (Feb 1978), 133

Well, if so, that would be strange. The aspirations that had led him through failed works and his series of nursing mothers (which do not look like work from the same artist) to a statue revealing the nature of love, are aspirations that cannot be surpassed. To materialize in a statue a transcendent and universal meaning, satisfying the intent of Communard artists to bring work of spirit-building insight to the people, that, surely, is a formulation of an artist’s “highest aspirations”. Beside this all the purposes that artists ordinarily claim seem not to amount to anything.

— FOR ADAM G.

.

Artist

Aimé-Jules Dalou (1838–1902)

Date

1876

Collection

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Titled there

A Young Mother from Boulogne Feeding her Child /

Boulonnaise allaitant son enfant

Medium

Terracotta, on the original wooden revolving base

Dimensions

137 cm | 54 in.

base, 90 cm | 35½ in

Photo source

Sotheby’s; Nadia Tingley

The header at the top of the page shows a bronze head of La Boulonnaise made by Dalou in 1883, now in a private collection in Brussels