Metaphysical vegetables | Sánchez Cotán’s Cardoon and Carrots

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | Strangely austere still-lifes

Juan Sánchez Cotán was born in Spain in 1561, in Orgaz in the province of Toledo, south of Madrid, and then worked as an artist in Toledo.

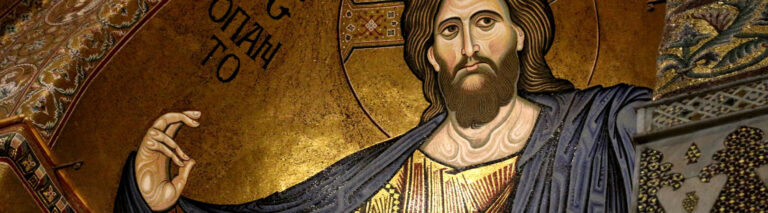

Some say he became, presumably when young, a student of Blas del Prado, a portrait painter to the court of Philip II in Madrid who also produced works on religious subjects, the best known of which (according to the British Museum) is [the image shown here],  The Holy Family with Saints Ildephonsus, John the Evangelist, and the Master Alonso de Villegas (1589, Museo del Prado, Madrid) – a work clearly influenced by Raphael. Del Prado was credited by Francisco Pacheco (the teacher of Velazquez and the author of The Art of Painting, the most important Spanish treatise on art) with introducing still-life painting to Spain, though no example of Del Prado’s work in that genre survives. Others, however, think that a link with Del Prado (who died in 1599) is only conjectural. But enough background.

The Holy Family with Saints Ildephonsus, John the Evangelist, and the Master Alonso de Villegas (1589, Museo del Prado, Madrid) – a work clearly influenced by Raphael. Del Prado was credited by Francisco Pacheco (the teacher of Velazquez and the author of The Art of Painting, the most important Spanish treatise on art) with introducing still-life painting to Spain, though no example of Del Prado’s work in that genre survives. Others, however, think that a link with Del Prado (who died in 1599) is only conjectural. But enough background.

Little information on Sánchez Cotán’s life seems available but it is known, as curators at the Prado museum put it, that

the turning point in Sánchez Cotán’s life came at the age of forty-three, when he decided to leave Toledo and become a Carthusian monk. In September 1604, he took his vows as a lay brother at the charterhouse in Granada and in 1610 he resided at the charterhouse in El Paular (Segovia [north-west of Madrid]), where he and his nephew, Alonso Sánchez Cotán, painted an altarpiece for the parish church of San Pablo de los Montes (Toledo).”

Becoming a Carthusian lay brother, then, did not mean the end of painting. For instance, the Immaculate Conception painted by Sánchez Cotán [seen at right] is given the date “between 1617 and 1618.” According to the curators of a museum in Granada,

Becoming a Carthusian lay brother, then, did not mean the end of painting. For instance, the Immaculate Conception painted by Sánchez Cotán [seen at right] is given the date “between 1617 and 1618.” According to the curators of a museum in Granada,

until his death he dedicated himself to decorating the different rooms of the monastery [he had joined] with Marian themes, evangelical scenes, and episodes from the history of the Carthusians.”

s.v. “Inmaculada Concepción,” Museo Bellas Artes de Granada

Around a decade after he took his vows, Sánchez Cotán was transferred to Granada (much further south near the Mediterranean), where some fifteen years later he died.

THE STILL-LIFES

It does not seem to be known when, exactly, Sánchez Cotán painted the group of pictures that have been called

among the most astonishing of early still-life paintings….”

T.J. Gorringe, Earthly Visions: Theology & the Challenges

of Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 145

The curators of the Prado claim that “most of” his still-lifes were painted “before 1603”; professor of theology Timothy Gorringe says he painted “in Toledo around 1600”; and virtually all the still-lifes by Sánchez Cotán that I have come across are assigned ‘circa’ dates by the museums owning them: “c. 1600”, “c. 1602”. In other words, these are educated guesses.

The curators of the Prado claim that “most of” his still-lifes were painted “before 1603”; professor of theology Timothy Gorringe says he painted “in Toledo around 1600”; and virtually all the still-lifes by Sánchez Cotán that I have come across are assigned ‘circa’ dates by the museums owning them: “c. 1600”, “c. 1602”. In other words, these are educated guesses.

Why pick 1602, the year before he joined the Carthusians? Not because as a monk he was required to stop painting; we have seen that he continued to paint. Perhaps it is because one still-life now in the Prado in Madrid is actually dated “1602” by the artist himself (who also added his name).

Still, the Prado says “most” of his still-lifes were painted before the year he joined the monks, so what was called “the turning point in Sánchez Cotán’s life” post-dates the work and group of works that we are interested in here.

What makes these works stand out? Their austerity.

2 | Still-life with cardoon

In this undated still-life in the Museum of Fine Arts in Granada we are presented with, says Gorringe, an

extraordinarily spare”

Gorringe, Earthly Visions, 145

group of vegetables, which take up less than half the area of the picture. Gorringe writes,

Cotán’s favourite framing space was a cantarero or cold larder, where the objects are set against a black and fathomless space.”

This would be a closed room or chamber whose masonry, entirely out of the sunlight, stayed cool, and could be used to keep foods fresh.

The cardoon, a celery-like vegetable, is propped against the right wall of the larder, in the full light, the earth on it still visible. The carrots are placed over each other forming a complex group and all overlapping the sill, demonstrating the illusionistic virtuosity of the painter. The suggestion that this still life echoes the vegetarian rule of the Carthusians, or that it may be a Lenten still life, seems plausible but whatever its religious provenance it forms an astonishing contrast to the work of a contemporary of Cotán’s such as Rubens, with his emphasis on historical or mythological themes. Why should anyone be interested in a few vegetables?”

Gorringe, Earthly Visions, 145–46

Why indeed.

Given that

still-life painting was virtually nonexistent in European art before the 1590s, … Juan Sánchez Cotán [being] among the first practitioners of the genre,

“Still Life with Quince, Cabbage, Melon,

& Cucumber,” San Diego Museum of Art

why did Sánchez Cotán revive this more ancient genre by representing the particular things he chose?

Still-life was much practised in the ancient world … but the tradition died out and it does not re-emerge as a subject in its own right until the 16th century.

Peter and Linda Murray, s.v. “Still-life”, The Penguin

Dictionary of Art and Artists, 5th ed.

(Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983), 396

Or come at this same question from a higher level, asking: what is the purpose of art and how would works like this accomplish it?

3 | The purpose of art & problems of purpose

Nietzsche raised this question after hearing the expression (that is, after being repelled by hearing it)

“l’art pour l’art”, literally ‘art for art’ – usually translated to English as art for art’s sake, meaning art as an end in itself. He wrote,

The fight against purpose in art [which Nietzsche judged rampant in the 19th century] is always a fight against the moralizing tendency in art, against its subordination to morality. L’art pour l’art means, ‘The devil take morality!’ But even this hostility still betrays the overpowering force of the prejudice. When the purpose of moral preaching and of improving man has been excluded from art, it still does not follow by any means that art is altogether purposeless, aimless, senseless – in short, l’art pour l’art, a worm chewing its own tail. ‘Rather no purpose at all than a moral purpose!’ – that is the talk of mere passion.”

Friedrich Nietzsche. The Twilight of the Idols or

How to Philosophize with a Hammer (1889),

trans. R.J. Hollingdale [melded with the trans.

of Walter Kaufmann], 81

According to the new idea that Nietzsche was rejecting, art has no purpose; its purpose is to be art, to be itself, just to be, as art. But Nietzsche believed that art – by being art and answering to art’s own demands – had a cultivating impetus, that it could not be understood in isolation from life, understood as the impetus to live: that is, to go in one direction and not another, toward life (instead of decay). Art that is aimed at being itself has nothing by which to be anything at all.

We have strayed here into the problem that we encounter wherever we attempt to talk about something as an end in itself, as a thing done for its own sake. Traditionalists like to fall back on this notion and it is in no way a mistaken notion; it is a distinction that is logically necessary if we are to escape the mess created by making everything instrumental: done for the sake of something else. But the idea of an end in itself is more difficult to manage than we suppose, and the thinkers whom traditionalists like to call on saw this.

Thomas Aquinas, for instance, asked about the purpose of virtue, of acting excellently. Isn’t virtue without a purpose, its own purpose? Isn’t excellence “to be loved for its own sake” and pursued for itself? His answer was no. Peter Kreeft captures the essence of his argument with a nice image:

If the soul were its own end, this would be as if a moving arrow were its own target.”

Peter Kreeft, A Summa of the Summa:

The Essential Philosophical Passages of

St. Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica

(San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990), 374 n. 63.

The arrow moves: the soul longs. But why, if they are the destination?

Just to be what it is art involves itself with something. Nietzsche wished to name that thing – or rather to name the purpose of that involvement, to name the function of art, the thing that art does.

A psychologist, on the other hand, asks: what does all art do? does it not praise? glorify? choose? prefer?”

Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, 81

Ironically, perhaps, all of these purposes named by Nietzsche are clustered around the good. Though Nietzsche had written a book he titled Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche was a classicist and highly sensitized against the prospect of a culture that made no such positive affirmations. What we “praise” we praise for the qualities we find praiseworthy – good. (Nietzsche’s thesis in Beyond Good and Evil, re. ‘good’, was simply that we ought to understand ‘good’ as this kind of affirmation-by-us, the things affirmed by us changing over the course of our lives.)

Likewise, what we “glorify” in a thing (another term he used, one with a distinctive history: it appears repeatedly in the Psalms, Isaiah, the four Gospels, and the Epistles) are its surpassing and excellent qualities. When we “choose” or “prefer” a thing we do so for the good (the meaning, pleasure, or advantage) that the chosen thing gives us, which are things we value.

Sometimes the meaning of art is identified with its life-enhancing character (an expression that seems to have been derived, actually, from Nietzsche). In his treatment of history Nietzsche had written against historians who promised to strip interpretation from history and give us ‘straight history’. If so, he had said, that product would not be history, which is open to

those who alone are capable of learning from that history in a true, that is to say life-enhancing sense.”

Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Uses &

Disadvantages of History for Life (1874),

in Untimely Meditations, trans. R.J. Hollingdale

(Cambridge University Press, 1997), 71

That is, the truth of historical narratives (say, the history of the United States) involves an interpretation of the events that ties that narrative to something that matters. Narrate history without the glory that is somewhere in it and you give us no account of human beings in time. The parallel with art is fairly clear. The advocates of art-for-art’s-sake who want, by isolating art from life, to show us the work of art itself are manufacturing, for some reason, an inhuman product.

We needn’t wade any further, just now, into question of the meaning of art. Pick whichever view of art you wish from these options (art as a rarefied thing-in-itself, art as praise and glorification of something, or art as life-enhancement): how is a picture of vegetables (especially such vegetables) art? How could such a depiction fill the bill of art as something meaningful?

4 | The point of a picture of vegetables

The celery-like cardoon in this picture has everything that is interesting cut off: its leaves, flowers, roots (with their complex shapes) are gone. It has no colour to delight us, being colourless and white (cardoons are ‘blanched’ with mounded soil, starving the edible stalk of light to keep it from turning green and woody). The straight shapes of the carrots, the main one just as pale as the cardoon (Gorringe calls it a parsnip), do little to create visual interest. So what is there (employing Nietzsche’s famous word) to value here?

Nietzsche continues:

With all this [i.e., the above praising, glorifying, etc.] it [i.e., art] strengthens or weakens certain valuations. Is this merely a “moreover”? an accident? something in which the artist’s instinct had no share? Or is it not the very presupposition of the artist’s ability? Does his basic instinct aim at art, or rather at the sense of art, at life? at a desirability of life? Art is the great stimulus to life: how could one understand it as purposeless, as aimless, as l’art pour l’art?

Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, 81

What “stimulus to life” could we see here? And, no less, what stimulus to piety? Recalling again that “turning point in Sánchez Cotán’s life”, what, here, aligns with religion – or did he actually quit the subject of still-lifes after entering the monastery because the subject had no spiritual substance?

Gorringe writes,

Even today they [Sánchez Cotán’s minimalist vegetable portraits] do not suggest themselves as a likely theme for art, but this artist manages to invest what we consider as trivial, ephemeral, the quintessentially domestic, with a truly metaphysical significance.”

Gorringe, Earthly Visions, 146

But how could such a work have a “metaphysical significance”?

‘THE POINT’ OF A VEGETABLE, I

I have raised the question of the function of a work of art, asking, What is a painting doing that gives us these vegetables in the way Sánchez Cotán depicts them?

Consider first the way he has decided to present these vegetables: you cannot miss that he is simply showing them all by themselves, in isolation from virtually everything. But then, to what end?

The ‘framing’ that is the opening of the cold larder is likewise reduced, to a simple presentation device: a bare ledge on which to put the focal items. (There is no hint even of any door on this larder, which would single it out as part of a house; setting is altogether avoided, as in other variants this artist painted.)

Further, in the still-lifes by other 17th-century artists described by Gorringe we have an implication of abundance, of the fact of providence, an implication of very many still-lifes to come, as in this tour-de-force by Nathaniel Bacon.

That is expressly not the implication of the cardoon and carrots. The one ‘theme’ that could be said to unite what is shown in Sánchez Cotán’s still-lifes is food. Other still-lifes he painted with vegetables include fruit and game birds, hung on threads (done to ripen them for eating, as I remember my father doing with woodcock). It is all food. There are, for instance, no utensils, as we see in later still-lifes (like the work by Francesco de Zurbarán, of 1633, that includes a basket, pewter plates, and a small ceramic cup).  Francisco de Zurbarán. Still-life with Lemons, Oranges, and Rose. 1633

Francisco de Zurbarán. Still-life with Lemons, Oranges, and Rose. 1633

That is, in Sánchez Cotán’s still-lifes there is nothing man-made. The entire class of things is fruits of nature, in that generic sense: edible things furnished by nature, which is to say, created by God for our consumption.In that, there is certainly a hint of the issue of providence (if this is restricted to provision, with no emphasis on abundance), but all the attention is on the things, which are displaying their own nature.

For one thing, they are shown almost independent of us. By no means wholly detached from us, because they have been harvested, as food, and set out on a ledge, but only in a way that emphasizes the individual thing, each thing isolated on its own. Notice too that the vegetables are not presented prepared, or with any especially desire-inducing qualities. The melon in the still-life by Sánchez Cotán in San Diego

has been cut open, with a slice set beside it that is ready to eat – here we do have a piece of fruit that has gustatory allure, so to speak – but none of the other items in Sánchez Cotán’s paintings have such a quality. Nor indeed does his choice of vegetable whet our appetite (a cabbage never entices you to bite into it). What is primary in these pictures is not the particular attractions of these things, as foods, but the knowledge that that is what we are seeing: these common things that we eat.

THE NATURE OF THINGS

When I say that the artist turns our attention to the things, in their own nature, might he have been giving some attention to what it means to have a nature – that is, by contrast with the preoccupation of most still-lifes with making use of the appearance? Caravaggio, in the Basket of Fruit he painted at around the same time, arranged his fruits and leaves to make an active and engaging outline that runs across the picture. He employs the shapes to make a composition, a new shape, and uses the colours in much the same way (the green of the leaves is spaced out nicely) to make a pleasing harmony, the harmony of the picture itself. Sánchez Cotán is doing

something very different. Is it focusing on the nature of the thing (not just its appearance)?

What is the nature of things?

For one thing, it is the nature of a thing to have a form – that form by which we identify the thing as what we call, say, a carrot. But, if you think about it for a moment, that is what is being done in every picture of things we encounter: that is representation. A thing shown in a painting is made identifiable as, say, a tree by way of the tree form. It does seem that we are allowed to identify every single thing captured in images, including photographs, by way of the form that that thing actually has – indeed, this is an identification we can make because some component of that form (the shape, say) is transferred to the image, either precisely or approximately.

In the painting by Magritte that has been made so much of in philosophy – the issue being ‘The Treachery of Images’ raised in its title – the pipe in the painting is indeed not a pipe: it is an image of a pipe: and it is so because it possesses (entirely without treachery, rather with obedient fidelity) the actual profile of a pipe.

Any suggestion that Sánchez Cotán is involved in presenting the nature of these things must involve more than attention to the thing’s form.

He first of all isolates things, takes them out of the setting in which the thing is usually found (the ordinary setting in which a carrot is just one thing among many). It is, in a sense, as if a playwright were to free the actor from the drama so that we could see the agent outside of any action, not doing but being.

But of course we are courting trouble in saying this: it would surely be a mistake, for instance, to take that next step and suggest that the cardoon on a bare stage is more really itself than when it is growing, or in the stew. It is itself in growing, rooted in the ground bearing its leaves, and also in being harvested, and also in being cooked, and eaten. So I avoid taking such a step. But think about the cardoon in the mind of God. The metaphysical form of the cardoon is in fact not a cardoon but only its blueprint, a form for matter.

But of course we are courting trouble in saying this: it would surely be a mistake, for instance, to take that next step and suggest that the cardoon on a bare stage is more really itself than when it is growing, or in the stew. It is itself in growing, rooted in the ground bearing its leaves, and also in being harvested, and also in being cooked, and eaten. So I avoid taking such a step. But think about the cardoon in the mind of God. The metaphysical form of the cardoon is in fact not a cardoon but only its blueprint, a form for matter.

In relation to the cardoon consider some basics of metaphysics, well explained by Etienne Gilson.

Beings which come to us in sense experience, we … designate … by the term ‘substances’. Each substance forms a complete whole which has a structure that … constitutes an ontological unit capable of being given a definition.

Etienne Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas,

trans. L.K. Shook (1956; University of Notre Dame Press, 1994), 29–30

That is, there is a set of defining features that distinguishes the cardoon from every other plant and thing. Gilson, however, notes that many have tended to think that this establishes what things are; that if we have a blueprint for a thing (in its definition or form) and then add to that form matter (to materialize that thing), then we have an existing thing, like the cardoon on the ledge. But no; existence, says Gilson, is primary: it has

radical primacy … over essence.

Gilson, 34

In so far as substance can be … defined, it is called “essence.” Essence, therefore, is only substance as susceptible of definition. To be exact, the essence is what the definition says the substance is. … To signify what a substance is, is to reply to the question ‘quid sit’ (what is it?), and so,

to the extent that it is expressed in the definition, the essence is called the “quiddity.”

Gilson, 30

Ordinarily, when we talk about the nature of things we give our attention to what I have just explained: the essence of things, the blueprint that defines them. What people ignored, until St. Thomas Aquinas (and many have done so after him, pushing this aside and continuing to fixate on essences), is

the mystery of actual existence.

Gilson, 31

Why does Gilson say this?

We might propose that the nature of the cardoon is decided by its form, a form conceived by God that we might think of as that blueprint specifying the essential parts or features of this thing (features by which we locate and identify it), but specifying also the thing’s potentials, such as the cardoon’s capacity to grow – the ‘plans’ thus encompass all the stages of the thing’s life, from seed to mature plant, and extends even to its value in the stew, another potential of its particular constitution – in that the cardoon was created to have that quality that turns out to make it desirable as food (Thomas Jefferson grew cardoons, imported at some point from the Mediterranean, which can be seen today in the vegetable garden at Monticello). Yet the cardoon was not conceived to inhabit the mind of God but rather to exist.

We say … that every substance implies a form, and that it is by virtue of this form that a substance is classified in a determined species, whose concept the definition expresses.

But,

on the other hand, it is also a fact of experience that species do not exist as such. ‘Man’ is not a substance [– a being]. The only substances we know are individuals. There must be, therefore, some other element than form, something that distinguishes members of the same species from one another…. Let us call it matter.

Gilson, 31

Yet, strangely, matter does not exist. Material like wood and cellulose exist, in beings like trees and cardoons, but we are talking here of what is added to the form of a cardoon to materialize it,

We know that it is not the matter by which the substance is, because matter cannot have existence apart from some form. It is always the matter of a substance…. Taken precisely as matter, quite apart from that of which it is a part, it does not exist.

Gilson, 32

Gilson then quotes Thomas Aquinas, who wrote,

Indeed, the act-of-existing is the act of something about which one can say: this thing exists. Now we do not say of matter that it exists. We only say this about the whole thing. We cannot therefore say that matter exists. It is the substance itself which exists.”

Aquinas, Summa contra Gentiles, 2, 54; cited in Gilson, 32

The cardoon exists, and neither its form nor its matter make it exist.

The proper role of the form is … [simply] to constitute substance as substance.”

Gilson, 32

That is, the form makes a thing the kind of thing it is, but it does not make that thing exist (when we talk of ‘forming’ a thing we erroneously treat giving-shape-to and making-exist as if they were one, as if matter already existed, just needing a form to become a nameable thing). But a phoenix is a nameable thing. Thomas Aquinas wrote,

I can have a concept of [a] phoenix, without knowing whether it exists in nature. It is therefore clear that the existence (‘esse’) is something other than the essence or quiddity.

Aquinas, De Ente et Essentia, 4; cited in Gilson, 38

(There are indeed unicorns, phoenixes – something shaped into these forms – that do not exist.)

Once it has been explained why a being is what it is, there remains to explain what makes it exist. Since neither matter nor form can exist apart, it is not difficult to see that the existence of their composite is possible. But it is not so easy to see how their union can engender actual existence. How is existence to arise from what does not exist? It is therefore necessary to have existence come first as the ultimate term to which the analysis of the real can attain. When it is thus related to existence, form ceases to appear as the ultimate determination of the real.

Gilson, 33

To explain why I have gone into this – which I am certain is far from clear – the quiddity of the cardoon is the cardoon-ness of the thing, which the cardoon presents, and this is also given us by Sánchez Cotán (who depicts some of the features that define the cardoon and the carrot). But his painting is also giving us the existence of the cardoon, in its blunt extraordinariness. This I may be able to explain by contrasting this painting with a different type of image.

5 | Not a scientific illustration

The kind of image that was developed to put before us not an existing thing but the quiddity of a thing, the distinguishing form of a thing – the image meant to represent precisely a species – is the scientific illustration. There is an interesting difference between the two kinds of image.

Scientific illustrations, such as this one of a cardoon from a book by virtually an exact contemporary of Sánchez Cotán – the Hortus Eystettensis by  Basil Besler (1561–1629) – take care to include and clearly delineate all (or at least enough to count) the identifying structures: the flower, the fruit, the leaves (this image lacks the roots, which are less relevant if the book is produced to help identify the growing plant, whose roots are not visible). What the illustrator is depicting is the plant not as we see it in nature (where these distinguishing features might be missing, the plant being damaged, etc.) but arranged by the artist in such a way as to make these identifiers fully visible (the leaves turned so as to give us the most intelligible profile, etc.).

Basil Besler (1561–1629) – take care to include and clearly delineate all (or at least enough to count) the identifying structures: the flower, the fruit, the leaves (this image lacks the roots, which are less relevant if the book is produced to help identify the growing plant, whose roots are not visible). What the illustrator is depicting is the plant not as we see it in nature (where these distinguishing features might be missing, the plant being damaged, etc.) but arranged by the artist in such a way as to make these identifiers fully visible (the leaves turned so as to give us the most intelligible profile, etc.).

Sánchez Cotán is in fact doing something like this, by isolating each vegetable to make its shape perfectly clear, but his object is not ‘the plant’, the natural species; it is something else. His painting is no more a painting of ‘cardoon’ than an artist’s self-portrait is a painting of ‘man’. ‘Man’, remember, does not exist, to have a likeness (but comes to be only in the existence of actual human beings).

Form (what scientific illustrations like this aim to single out) makes the substance or being to be a cardoon, but it does not

make the substance to be a ‘being’.

Gilson, 33

The things we experience in the world, including each other, are

beings whose existence finds no justification in their own essence. It is this that is the distinction between essence and the act-of-existing. And because it is profoundly real, it poses the problem of the cause of finite existences, which is the problem of the existence of God.

Gilson, 36

I have had to take this long detour into metaphysics to get where I am going: to uncover the existential quality that is contained in an arid picture of two kinds of vegetable. The ‘existential’ reality I mean is not a 20th-century thing but belongs to the age of Sánchez Cotán.

When Gorringe suggested that in this painting

this artist manages to invest … [the cardoon, the carrots] with a truly metaphysical significance,

Gorringe, Earthly Visions, 146

was it this that he was referring to: a thing displayed with its defining features (metaphysics being just that corner of thinking that deals with essences and forms). For Aquinas, there was more to these vegetables than that; that is, what appeared to me in play, at first, was the radical presentation of lowly things shown to us as having essential qualities, but it appears to me that more is going on.

This picture is very far from a scientific illustration, where plants are often made somewhat decorative and pretty – fully appropriate for an image if you still shows what features identify the species presented. (With what Sánchez Cotán gives us, could we so easily locate the cardoon in the garden? Take the two images and try your luck to spot the cardoon in this excellent video. – Which image helped?) In scientific illustrations existence is not a theme.

6 | Existence & destiny

We are invited, by the sparseness of the painting, to contemplate these two isolated substances – beings of two kinds – against the backdrop of nothingness. The black of the larder cannot really be the black of a larder when we are scarcely prompted to think of any larder: what we are seeing is a void. This has been noted by others. In

the Still-life with Quince, Cabbage, Melon, and Cucumber … the quince and the cabbage hang on strings against the same black space, ‘turning and glowing like planets in a boundless night’.”

Gorringe (citing Sterling), Earthly Visions, 146

According to Genesis the first formed thing (the first thing given an essence) and the first thing made to exist (a thing endowed with what Aquinas calls the “act of existing”, which seems a kind of power given t that thing) was light, followed by darkness, the second thing. (This is difficult to understand, and yet you realize that there was nothing to light up.) It is hard not to see the lightless nothingness of Sánchez Cotán’s background as anything other than the empty realm of nothing. But that nothingness is countered here by existence, the existence of the the cardoon and the carrots, sitting here on the ledge (and we too exist, in the same way).

The cardoon and carrots are quite unlike that background: while it is unrelievedly black (‘nothing’ has nothing to differentiate) they are both differentiated and complex, and bathed in the light that reveals this about them. This is another quality of existence: to be receptive to light, which illuminates the qualities of a thing’s being, reveals it. Things that exist absorb and reflect light. The lightless void that fills fully half the area of the painting is a kind of counter to existence. So the few actors on the stage of the painting have already presented these alternatives: there could be nothing … but instead, things exist.

The point of the still-life is already far-removed from the point of the scientific illustration, which is identification. The painting has delivered us the cardoon as a reality made to exist – made to because that is not a part of its essence. Looking at a vegetable, a tree, a man, clearly

their essence is to be either a tree or an animal or a man. In no case is it their essence to exist.

Gilson, 35

Even in the mind of God the form of the cardoon was ‘formulated’ relative to creation, to give a thing particular being in the world: to give the thing existence. The form was conceived not just to be filled with matter but to do so in existence.

Again, recall that in the painting we are seeing not so much a ‘natural species’ as food, which is the species brought into the condition to be enjoyed, by those for whom it was grown. We can see this, as I have noted, providentially, as the natural food that is given us by nature (that is, by God), and in the form of individual cardoons existing in the world – indeed in our very pantries. In that way we are enabled to contemplate the providential reality of a Creation that might have withheld not just food but existence itself.

But we can also look at this existentially, wondering why there is existence of any kind, when once there was nothing but God alone. The cardoon envisioned in the mind of God was not a cardoon but a form: but it is existing, embodied cardoons, such as we see in the still-life, that were already planned. There is not just essence (spelling out what philosophers have called the “definition of the thing”); there is also existence.

Cardoons and carrots were created not simply to be metaphysically, as embodied forms in the mind of God, but to exist physically and have their own lives, which is – according to that plan – a life that can be lived only in the world. The cardoon in the mind of God drinks no water. It was conceived to exist, and pass through all its life phases, acquiring the qualities that make it desirable, that put it on the table.

When we say that Sánchez Cotán’s still-lifes all show us food we are saying that he has painted things that have become good and pleasing to those whom they are for. Vegetables that have matured, have become ready for harvest, to be consumed by those for whom they were grown, who will enjoy them.

Existence is a mystery, for why should this or that thing exist at all, this odd looking vegetable? The Scriptures answer,

for thou hast created all things, and for thy pleasure they are and were created.”

Revelation 4:11 KJV

What is existence, what is our own existence? Everything exists to be the thing it is, created for the pleasure of God. We consume the food for its goodness, and take it into us. For our goodness – should we live the life that we were given existence to live (each thing being what it is, which we were taught in Genesis 1 is good) then we too will be taken into something very much more splendid than us. We will become part of the body of the LORD.

Those who say they are part of the body now in belonging to the Church are not paying attention to the transformation that the plan I have just described. The translations do not always capture what being made part of the body when God completes it involves.

For the LORD takes pleasure in his people; he adorns the humble with salvation.”

Psalm 149:4 ESV

The King James version conveys more richly the transformation involved in the reception of what pleases God.

For the LORD taketh pleasure in his people: He will beautify the meek with salvation.”

[]

How is a picture of vegetables, a picture indifferent to aesthetic appeal, art? What is the purpose of art – might it have to do, as Nietzsche suggested, with life? It might have to do with the understanding of life, the encouragement to become part of it.

And how would such humble works accomplish a high purpose? Sánchez Cotán’s picture is a kind of evocation of the nature of all things, and particularly humble things. That is the purpose of humble things: to please God, by being. Is this painting not an encouragement to participate in being and existence when life is so commonly given a thousand other conceivable purposes?

Artist

Juan Sánchez Cotán (1561–1627)

Date

c. 1602

Collection

Museo de Bellas Artes de Granada

Titled there

Bodegón del cardo (Bodegón con cardo y zanahorias) | Still-life with cardoon (Still-life with cardoon and carrots)

Medium

Oil on canvas

Dimensions

62 x 82 cm | 24 x 32 in

Photo credits

Museo de Bellas Artes de Granada

.