Ideal government III | Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Vision of Justice

In this essay,

• ESCAPE FROM DISCORD

• JUSTICE

• KINDS OF JUSTICE

• FRAUDULENT JUSTICE, OR, THE REPUBLICAN FACTOR

• SUMMATION

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | Escape from discord

We are continuing to look at a late-medieval fresco by Ambrogio Lorenzetti that the historian Quentin Skinner called

the most memorable contribution to the debate [about proper government at this time]. This took the form of the celebrated cycle of frescoes he painted between 1337 and 1340 in the Sala dei Nove of the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena.”

Quentin Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher,”

Proceedings of the British Academy 72 (1986), 1

Part 14 of this series considered the western wall, at left above, which bears an image of Siena in discord, subject to tyranny. Here we turn to the central wall of this room, in which a plan of escape from that fate is laid out.

Part 14 of this series considered the western wall, at left above, which bears an image of Siena in discord, subject to tyranny. Here we turn to the central wall of this room, in which a plan of escape from that fate is laid out.

THE ‘SALA DEI NOVE’ OR ROOM OF THE NINE

The visitor to the Room of the Nine, entering through its original doorway, faces the west wall and its portrayal of Siena in misery. First, as noted in the last instalment, is seen the desolate state of the country and city, and the scene then shifts to an explanation for this state, presented via personifications that signify unjust rule.

Turning to the right, the visitor faces the room’s central wall.

The inscriptions are most densely concentrated on [this] middle wall. In the painted frame around the frescoes we find long captions…, identifying labels on the base of quatrefoil medallions, painted tablets with texts of several lines, and on the middle wall the artist’s ‘signature’. Within the scenes figures are labeled, scrolls or banderoles inscribed, letters and words written on the objects represented; initials form a nimbus, and a biblical text is quoted in an arc – Diligite iustitiam q[ui] iudicatis terrain (Wisdom of Solomon 1:1). So many words strategically patterned as an armature of writing command attention even before they are read.

Randolph Starn & Loren Partridge, Arts of Power: Three Halls of State in Italy,

1300–1600(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 28

On these inscriptions and the work they do here (making precise what the images – “scales of justice, olive branches of peace, scepters, shields, swords” – would leave ‘indeterminate’), Starn and Partridge write,

The lengthier inscriptions issue peremptory commands, supplying stage instructions for the pictures and cues for the reader’s response. But none of these lines grant a voice to the figures; they make declarations about them. The seductive indeterminacy of the image is suspect in these frescoes celebrated for their visual appeal. Writing takes the privileged, literally the prescriptive, role.

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 29

(At least, so say the scholars.)

The space on this wall is divided vertically into three bands:

• at the bottom is the group of ‘the people’;

• above it is a raised platform on which sits a central group of personifications (the bench running across this platform is a throne of rule, on which sit those who ‘stand over’ and govern the people);

• higher still is the sky, a zone of pure blue: the heavenly realm that in turn stands over and directs the rulers.

The inscriptions here – the text written out in the fresco in both Latin and vernacular Italian –

name justice in seven places.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 43

2 | Justice

Scanning this wall from left to right we first encounter, on the middle tier, a triangular grouping of figures formed around the scales of justice. In this, the large seated figure clad in orange is linked, by her posture of enthronement, to the even larger figure, further to the right, of the bearded man in black and white.

Above the blonde head of the red-clad figure of Justice we read the opening line of the Book of Wisdom, inscribed in an arc in the blue: Diligite iustitiam q[ui] iudicatis terrain | Love justice you who judge on earth.

We saw this same verse held out to the Sienese by the hand of Christ in the fresco by Simone Martini in the adjoining room, which I discussed not long ago. Writes art historian Chiara Frugoni,

It is my impression that the biblical injunction from the Liber Sapientiae, ‘Diligite lustitiam qui iudicans terrain’, placed around the figure of justice, has [been overlooked]. This line, it seems to me, was intended to suggest to medieval spectators, and to us, how to read the entire fresco.

Chiara Frugoni, A Distant City: Images of Urban Experience In the Medieval World,

trans. William McCuaig (Princeton University Press, 1991), 124

This central figure is Justice herself. Consider too the symbol of the weighing scale (the instrument that delivers our notion of the scales of justice), a device that is also called a balance.

We see the structure here: two pans hang from opposite ends of the beam of the scales, which pivots on a fulcrum, a fixed point. In using the scales the ‘right measure’ (one pound of flour, say) is found when the pans are balanced (one holding a weight or mass of known weight, the other the flour), and that condition – balance, the two masses being equal – is what the user ascertains by seeing the needle of the scales align with the fulcrum, or, as seems to be the case in Lorenzetti’s scales, seeing the tip of the needle come to the centre of a circle. (Though somewhat difficult to see in the fresco’s current state, a fine line is visible in the small circle directly above the head of Justice).

The eyes of Justice are raised for this reason.  They are trained on that point, looking to what indicates that the balance has been found. In Lorenzetti’s image true Justice does not just stand for justice or hold her attributes; she is an active figure keenly attuned to establishing justice.

They are trained on that point, looking to what indicates that the balance has been found. In Lorenzetti’s image true Justice does not just stand for justice or hold her attributes; she is an active figure keenly attuned to establishing justice.

Sin, in the New Testament, is ‘falling short of a mark’ (it is not just hamartia that has this meaning but even Torah is linked to this). Here the symbol of the scales of justice shows us this mark that we are to hit (the line we must align with, the circle we must reach but not overshoot). It is a mark that we will fail to hit if we do not know what the mark is, or (glibly aware that we do know) if we are not looking at our actions (our acts of supposed justice) to see that in these acts (which are inevitably acts of balancing) that that mark is hit, in what we have chosen to do. In Lorenzetti’s fresco the figure of Justice does both. In looking above her – higher than herself –

• she looks first to heaven, knowing that the mark is set there, …

• and attuned as she is to Wisdom, she sees the mark to be hit, …

• and she looks also to ascertain that in her actions she has hit it.

This we are shown by the image. (The scholars who emphasized that “writing” here takes “the privileged, literally the prescriptive, role” should really have added, only where the image does not do all the talking.)

Where does this thinking come from, and how important is it?

THE SIGNIFICANCE

It is surprisingly important, as we might see by considering this in relation to ourselves. Both aspects of that single detail – the upward glance of Justice – stand as a lesson to us.

Lorenzetti and the councillors of Siena assert here that any judge (by which I mean not just jurists but legislators and governors of all kinds, people, who all make judgements of what is due others) … any judge that does not see himself or herself as subordinate to a higher order of justice will be unjust. Any judge who conceives justice not as a mark that is given to it – a mark not totally manifest but there to be discerned, by fidelity to this higher order of reality above it, by attention to Wisdom – any judge or judiciary that understands justice, instead, as something that it creates by its deliberations, will not be looking upward. For it, there is no fulcrum fixed in heaven that is to be used to see what is just and establish justice in its realm. If there is nothing in the heavens to be discerned these judges will be looking downward, at bad conditions among the people, … specific conditions that these judges pick out (by no wisdom but their own default sense of rightness), the correction of which the judiciary will elevate as the standard of justice! This will be ITS justice, and because it has severed the connection with heaven and turned entirely away from Wisdom (which it dismisses: there is no Wisdom to which it must look to be just) that government has thrown away its claim to majesty, the majesty of heaven, the ‘Maestà’ counted so crucial in the imagery of the adjoining room.

Lorenzetti’s prescription for earthly justice subordinates Justice to Wisdom. The entire apparatus of the scales depicted here hangs from the right hand of a crowned heavenly figure identified by gold lettering as SAPIENTIA, Wisdom.

Lorenzetti’s prescription for earthly justice subordinates Justice to Wisdom. The entire apparatus of the scales depicted here hangs from the right hand of a crowned heavenly figure identified by gold lettering as SAPIENTIA, Wisdom.

This is the figure encountered in the Book of Proverbs, personified there as female because the Hebrew word for wisdom is feminine ( חָכְמוֹת | Hokmah). As we noted in discussing Simone Martini’s Maestà (presiding over the room adjoining this one), Wisdom is identified with the figure of Christ. Scholars discussing the “personified” figure of Wisdom in Proverbs 8 note that wisdom is

the divine attribute specially employed in acts of counsel and admonition,”

and thus they see the personification of this quality as a stand-in for, or representation of, God. Others, however, go one step further and see the speech of Wisdom in Proverbs as delivering

the language of the Son of God under the name of Wisdom (compare Luke 11:49).

Robert Jamieson, A.R. Fausset, & David Brown, Commentary Critical and Explanatory on the Whole Bible (Oak Harbor, Washington: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1997), vol. 1, 391

‘Wisdom’ is the concept that joins the task of government to the purposes of heaven. The essential message of the fresco, given the centrality of justice to the work of government, is that the mark of justice is set in heaven, by Wisdom – indeed, note that the figure of Wisdom, holding the scales, herself looks upward (in the direction of the cross atop her crown, at the fresco’s upper limit). A government detached from or oblivious to Wisdom must be unjust.

THE SOURCE OF THESE IDEAS?

From where do these ideas come? From the Bible, certainly, but we can find advocates of this political philosophy in Italy just prior to Lorenzetti.

Commenting on the texts that are written out on the wall as part of this cycle, Starn and Partridge write:

Although there is no way of identifying the author (or authors) of the inscriptions, they may have been composed by Lorenzetti himself. Vasari [the first historian of art, writing in the Renaissance] recalled the painter’s reputation as a cultivated man, ‘esteemed in his native city … for having devoted himself to studies in his youth …, and always frequenting men of letters and scholars.’ … One of the few surviving books of deliberations by the Nine reports that ‘Magister Ambrosius Laurentii’ addressed an advisory council on 2 November 1347 sua sapientia verba. According to the notary’s minutes, Lorenzetti spoke in favour of proposals for expanding the political franchise, for strengthening the office of Captain of the People, and regulating conflicts of interest among officials.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 33

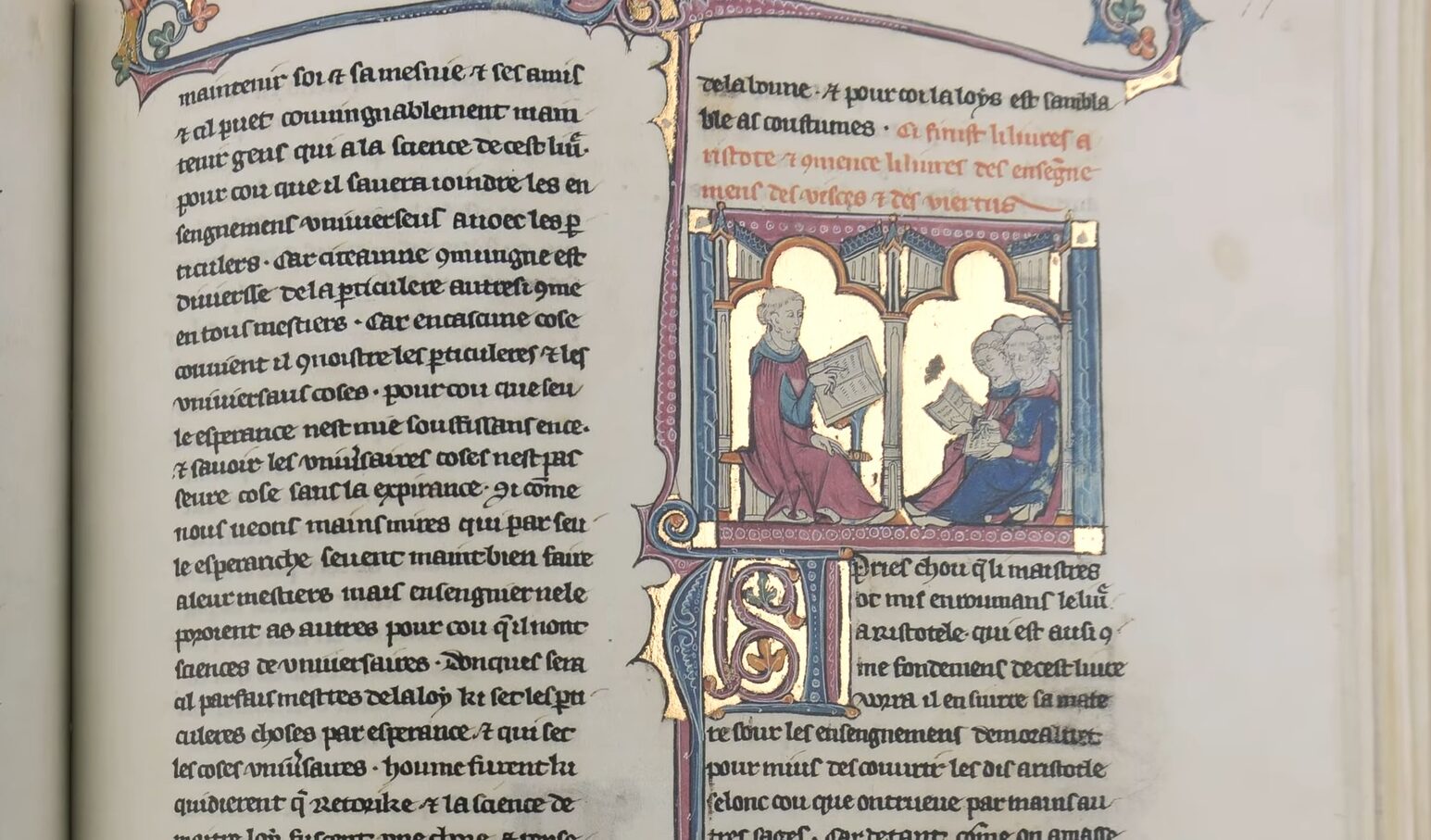

If Lorenzetti was a learned painter what books would he have drawn upon here? Thinking about late-medieval politics, most would bring up Thomas Aquinas (and thus Aristotle) but in the Room of the Nine, apparently,

there is only one inscription in the ensemble that may depend explicitly on St. Thomas or Aristotle.

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 40

Whoever it was who wrote the script for this room, that person

could have found … most of the texts they needed in the one book that was the acknowledged and, so the author tells us, the indispensable guide to politics, especially in a republican city-state. This was the Book of Treasure (Li livres dou trésor) by … Ser Brunetto Latini.

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 40

A Florentine teacher of Dante, Latini was exiled after the defeat of the Guelphs at the Battle of Montaperti at which (as we saw in essay 13) Siena was victorious. He spent that exile in France (the work just noted has a French title because it was written in French during his period of exile, 1260-66, though before his death in 1294 he composed a version in Italian). The ‘Treasure’ of the work’s title alluded to “the most precious jewels” sought by “rulers”.

What, we might ask, is the most precious such jewel? Indeed, we might say it is the answer to the central question we could ask about politics, which is What is politics for? Exactly that question was answered by Latini, an answer afforded us, he wrote, through “the highest knowledge”, which unfolded “the noblest duty there is on earth” (book 3, chapter 73.1). Here we have a direct reference to Wisdom, linked with

a passage from Aristotle that Ser Brunetto cited with approval.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 40

In the Treasure Latini had said that

justice must serve wisdom.”

Latini, cited by Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 44

For Christians, such as the Sienese, that “noblest duty” (the notion of nobility, recall, is linked with Aristotle’s arete or excellence) had been declared in the room of the Maestà, which, as we saw, had boldly announced the highest purpose of government:

participation in the glory of God

– or, rephrased to align with the regal imagery of the Maestà’s throne room:

to reign with God over His Creation, as beings who represent Him – who are images of Him, agents of His goodness, like-minded beings enacting His divine will.

For people today, however – or so it appears, even when we are Christians – that cannot be the ‘treasure’ sought by every man concerned with politics. Why? Because in our eyes this announcement just burdens us with a second question:

In what way could any ACTUAL state hope to accomplish such a thing?

That is the very question that the Room of the Nine undertakes to answer.

3 | Just acts

If we return to Lorenzetti’s image of Justice we can move one or two steps further down the path of the answer that is marked out for us in the fresco. The pans of the scales of Justice are labeled Comutativa and Distributiva. These are

precise technical terms [that] so far as we know … first appeared in the translation of Aristotle’s Ethics [c. 1250] generally attributed to Robert Grosseteste; Thomas Aquinas used them in the Summa theologica for his analysis of the equitable distribution and exchange of goods. Since neither Ser Brunetto Latini nor his sources employed this terminology, the conclusion seems inescapable that, at least in this one detail, Lorenzetti’s frescoes are ‘Thomistic Aristotelian’.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 44

On the left (from a position in the left pan of the scales) an angel, being a messenger (bearing the message of or illustrating what God considers due), acts as an agent of divine judgement and administers what is due. (To be clear, the issue is temporal, this-world judgement not eternal judgement; an execution is a this-world event carried out by the state.) Due action in fact returns us to the concept of balance that is central to the operation of scales.

When something is done to people that is undue, injustice occurs, and an unjust act merits a response: that response that is due to the perpetrator of injustice, the response that such an act deserves (from the ‘justice system’, as we would say today, somewhat problematically). Skinner notes that

[The French Dominican writer Guillaume] Peyraut [c. 1190–1271] opens his discussion of penal justice by explaining that it is simply a matter of rendering to malefactors what they deserve.”

Quentin Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher,” Proceedings of the British Academy 72 (1986), 15

This is the conception of “justice as dessert”, versus alternative ways of understanding what justice itself is (the topic of Alasdair MacIntyre’s Whose Justice? Which Rationality?). A due thing is a deserved thing (‘merit’ is a synonym of dessert). Thus we have the issue of balance, as noted in Latini’s Book of Treasure, which explains that

the just man may be said to equalize things. ‘He does so in two ways: one is by handing out money and dignities’”

– that is rewards and honours that are matched to, proportionate to, some prior action or condition that invites this response;

the other is by saving and paying back those who have received harm’.”

Skinner, “The Artist as Political Philosopher,” 16

A man who has been injured (by being robbed, say) is, when justice is done, ‘saved’ and ‘paid back’ in a way proportionate to the harm done to him.

This may seem quite self-evident, but this ‘self-evident appearance’ is explained by those who understand “justice as dessert” in one way, and explained in a completely different way by those who embrace a modern understanding of justice (according to which, as I have said, Justice does not ‘look upward’). In this image Lorenzetti and Siena assert that the mark of equality – the ‘justness’ of a particular punishment for a particular crime, and the ‘dueness’ of a compensation for an injury – is in the order of things that is ‘handed to us’ by Wisdom. If to be just we must see that balance is achieved, to see that balance is achieved we must assess correctly what each person is due: we must ‘discern the worthiness or merit’ of that person’s claim to honours, benefits, and rewards.

Link that view with the idea of a republic: it is not the case that the republican rulers who act on behalf of the people are to represent the people’s de facto understanding of that mark, the people’s judgement of balance and dueness. It is, instead – this is the view presented in the fresco – that the rulers are to look upward and take direction from heaven. They should not look down to the people and apply their measure of punishment or reward. It is the task of the Christian republic to enlighten the people, and the Book of Proverbs opens with an explanation of what that means.

To know wisdom and instruction”

is, the text explains,

to receive instruction in wise dealing,”

which a republic may set up and impart through institutions and via its own exemplary actions. This “instruction” will be instruction

in righteousness, justice, and equity; [imparted] to give prudence to the simple, knowledge and discretion to the youth….”

Proverbs 1:2–4 ESV

The members of this republic should thus strive to find the mark of justice that is set in heaven, because, in a Christian republic the people do not presume that they truly see what is just. The standard of judgement is not in them; it is above them, as we are shown here. In this image the three vertical tiers and the relation between them (of Justice to Wisdom, etc.) make this clear.

THE ‘JUSTICE SYSTEM’?

Here is a second point made clear by this image. I alluded above to a trap that all talk of justice lays for modern people, who are primed to think, ‘So you are talking about the justice system’. But in this discussion that is quite wrong (or, if we are, then the ‘justice system’ includes far more than we think it does).

‘System’ is a very poor word for what we are seeing in this image. What we have looked at thus far is not the judiciary but justice, our issue being to answer the most basic questions concerned with it (What is justice? Where does it come from? What can we use to find the just action?). Without answers to these questions how could we have, in our republic, actual justice? It will soon be clear, through the explanation of Justice presented in the fresco, that that is what is wanted in Siena: not justice in a ‘justice system’ but in the society as a whole.

The issue is, indeed, government, but Lorenzetti’s image will soon show us that in two different ways all the citizens of Siena govern society, in their lives:

- in the way one person acts toward another, person-to-person;

- and in the way groups of people (groups like the Nine councillors who met in this room, for example) act toward individuals.

What this image of Justice propagates (call it propaganda, if you wish, but this term, originating as it did in the Church, simply meant the propagation of faithful beliefs) is a manner of governing for the people of Siena. That is, the republican ideal we see here does not lay out a plan of behaviour for the rulers, the few officiating from the Palazzo Pubblico, but for the people of the city and its countryside. Lorenzetti paints a panorama of town and country (some have called it “the first panorama”) precisely because his republican conception of government is a government of the people: it is the people who will be just. The fresco advocates justice as the way of the Sienese people themselves.

Through the principles that we are discussing (justice as dessert, justice established by wisdom) the commissioners of this fresco were trying to engineer not a system of justice but a justice culture.

THE PANS OF THE SCALES

Once again, we see this in the image itself.

What we call the ‘justice system’ intervenes when wrong is done, but that is not what we see in Lorenzetti’s image of Justice. Justice indeed includes how wrong-doing is dealt with. Look again at the angel executing an offender who is … – aligned with what we have established thus far, a man whose actions merit death. (I am not making a case for capital punishment, just reading this 14th-century image.) He is, let us say (turning to a headline in my own country), a man who has killed his wife and two sons.

That act was the act of a member of the society and an act of injustice for being a deed done against other members of the society, which those members did not deserve. (It was an injustice of the most extreme kind, because it deprived all three people of every earthly good.) Thus we are already talking about justice – about a created ‘imbalance’, a disruption of due treatment – even before police, jailers, and judges get involved, as it is that disruption that gets them involved.

That act was the act of a member of the society and an act of injustice for being a deed done against other members of the society, which those members did not deserve. (It was an injustice of the most extreme kind, because it deprived all three people of every earthly good.) Thus we are already talking about justice – about a created ‘imbalance’, a disruption of due treatment – even before police, jailers, and judges get involved, as it is that disruption that gets them involved.

That criminal act is due a response and for justice to be done the particular response given must also be due: the punishment must fit the crime. The sword on the ground, fallen from the murderer’s right hand, makes an allusion to a Biblical verse:

All who take the sword will perish by the sword.”

Matthew 26:52 ESV

These words of Jesus are in effect a statement of the equality that is always at issue in justice (what does “the sword” call forth but “the sword”).

In this part of the image we ought to note the second person kneeling here before the angel. In this pair of men we see, it so happens, both sides of the coin of injustice: wherever there is a perpetrator there is also a victim, a person wronged.

We know that this kneeling man has been killed (and killed unjustly) because he holds the palm frond that in Christian art indicates a martyr. (The origin of that motif was the frond or laurels given as rewards to victors in Greco-Roman culture,  and represented in its art, a motif borrowed by Christian artists for their own ends – as I explain here in discussing the palm frond given to St. Catherine in a painting by Simone Martini now in Ottawa.) The palm in Lorenzetti’s image, however, simply tells us that this man was martyred: killed for the ‘offense’ of his Christianity – that is, he is a man executed unjustly, like Jesus. (Notice, then, that this left pan of the scales presents just and unjust executions.) In this image the reward that is due the martyr is located not in the palm but in the crown that is set on the victim’s head by the hand of the angel. If this is an image meant to show us just rewards dispensed by heaven (divinely ordained acts of justice), then it is in the angel’s hand that it must be placed.

and represented in its art, a motif borrowed by Christian artists for their own ends – as I explain here in discussing the palm frond given to St. Catherine in a painting by Simone Martini now in Ottawa.) The palm in Lorenzetti’s image, however, simply tells us that this man was martyred: killed for the ‘offense’ of his Christianity – that is, he is a man executed unjustly, like Jesus. (Notice, then, that this left pan of the scales presents just and unjust executions.) In this image the reward that is due the martyr is located not in the palm but in the crown that is set on the victim’s head by the hand of the angel. If this is an image meant to show us just rewards dispensed by heaven (divinely ordained acts of justice), then it is in the angel’s hand that it must be placed.

Turn now to the group in the right pan of the scales, where we are shown (says Skinner) just rewards received by heaven. In this group an angel again bends toward two figures, but here there are no swords – indeed, nothing at all to suggest any wrongdoing that awaits rectification by the state. That is, there is no role for our conception (the justice system) to play. On the right side of the scales we have justice without reference to wrongdoing.

What, actually, is occurring here is somewhat obscured by the difficulty of identifying the objects that seem to be passing between the men and the angel. (But who is giving what to whom?) Skinner notes that the action we are seeing

What, actually, is occurring here is somewhat obscured by the difficulty of identifying the objects that seem to be passing between the men and the angel. (But who is giving what to whom?) Skinner notes that the action we are seeing

might perhaps be interpreted as an exchange. The angel confronts two figures, and is usually said [i.e., by art historians] to be giving them various articles.”

But, he says, another reading makes more sense.

Since [the men] are both kneeling in the conventional posture of donors, however [– medieval people who commissioned paintings as gifts (donations) to a church often had themselves represented in just this posture in those paintings], it may well be they who are making the gifts. The [orange-clad] figure on the left definitely appears to be handing over two metal-tipped lances; the one [in green] on the right is holding out (and perhaps offering up) an object which, while it looks cylindrical, cannot in the present condition of the painting be further identified.”

Skinner, “The Artist as Political Philosopher,” 37–38

We may well be seeing donations made by two guilds (a metalworker offering spears, a clothmaker cloth, like a roll of felt – though the pigment that has blackened over time might have been silver, making this object a metal box: a strongbox of money, suggested Frugoni).

What makes Skinner’s suggestion seem correct is the way it brings out the duality that is usually suggested by the kind of left–right ‘opposition’ offered here by the two )differentiated) sides of the scales. What are the two things marked by these scenes of justice, if it is not that on the left the angel gives while on the right the angel receives?

Both, we should notice, constitute instances of divine justice. The balance issue that is central to justice we have already explored in connection with crime and punishment; we encounter the very same issue in connection with giving. What is heaven due? That too was answered by wisdom. We might look at our possessions and the fruit of our labours as justly ours, yet….

Beware lest you say in your heart, ‘My power and the might of my hand have gotten me this wealth.’ You shall remember the LORD your God, for it is he who gives you power to get wealth,….”

Deuteronomy 8:17–18 ESV

Numerous passages might be added to this one to indicate the justice of putting some portion of our property into the hands of God – or into the hands of those tasked by God with the doing of his work. (The angels on both sides of this image of Justice, are place-holders for the Sienese.)

4 | Complications

Having just made what seems excellent sense of Lorenzetti’s image, it would be nice to move swiftly ahead, but that is ruled out by complications that I would do wrong to ignore. Frugoni rejects the duality that we have just brought out.

As for the two angels on the pans of the balance, … how would a medieval observer (or we), who had not previously consulted the heap of sources raked up by Skinner, ever have managed to conclude that one angel gives, while the other ‘receives’, the various objects in question…, since each is making exactly the same gesture?”

Frugoni, A Distant City, 191–92

To this I might reply that I advanced Skinner’s reading on account of the sense it made of the image (not on account of the sources he adduced to support it, which I entirely ignored without cost). His reading made special sense for bringing out the duality that this two-sided image suggests is there, but that otherwise was not apparent.

Anyone looking at the fresco, however, might easily counter this claim simply by saying, What about the two inscriptions? – An excellent point.

PERSON TO PERSON, SOCIETY TO PERSON

I have till now said nothing of a prominent distinction, in this image, regarding justice – a feature that was once unmistakably visible but is quite easy to miss since the lettering has darkened and been virtually absorbed into the blue background. The instances of justice in the two pans of the scales appear to be labelled. (Are these labels?)

The titulus on the left reads [DIS]TRIBUTIVA, the one on the right COMUTATIVA.”

Skinner, “The Artist as Political Philosopher,” 37

Skinner identifies this as an Aristotelian distinction central to book V of the Nicomachean Ethics, and a distinction thus marked in both Robert Grosseteste’s translation of the Ethics (c. 1240s) and treated by Thomas Aquinas in his Summa theologiae.

As I have just said, I have read the images without help from these titles; I should perhaps explain why. My intent has been to show how these paintings could function as a form of ‘ideal political instruction’ to the Sienese citizen who meditated on the paintings in these rooms. Such a person could very likely have distilled, from examination of the images themselves, everything that I have said thus far. The specifications of distributive and commutative justice, on the other hand (note that in the image these terms are in Latin), could have resonated only with scholars. The Room of the Nine contains inscriptions in two languages: scholarly Latin and vernacular Italian, and they are used to say different things.

Was I wrong to identify the ‘two sides of justice’ presented by Lorenzetti in his two-sided image as What we are due, on the one hand, and What heaven is due, on the other? That may depend on how the images relate to that Aristotelian contrast, which we must now examine.

Unfortunately, there is something puzzling about the relation of these terms to the images they appear to label. Starn and Partridge say, bluntly, that

the terms do not fit what the pictures show – the crowning and decapitating ‘distributive’ angel and the ‘commutative’ angel giving (or receiving?) some round object (a strongbox containing money or a bale of fabric …) and two lances or spears.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 44

The way forward here is surely the get clear, first, on the meaning of these two concepts.

COMMUTATIVE JUSTICE, OR JUSTICE PERSON-TO-PERSON

We are fortunate that Etienne Gilson provides an excellent brief account.

First, he says, the distinction between these two ‘species of justice’ attaches to particular justice, that is, to the way people are treated. Apart from this is the separate issue of legal or legislative justice, but that, he says, is not what is presented in book V of the Ethics (or, we might add, in Lorenzetti’s image).

Second, in the treatment of particular people there are two kinds of relationship; if our concern with justice focuses on the relationship

between two private persons, it is a matter of commutative justice. If, on the contrary, it is a question of regulating a relationship between the whole [the whole society, or a group of some other kind, such as a guild] and one of its parts; that is, of assigning to some particular person his part of the goods collectively owned by the group, it is a matter of distributive justice.”

Gilson then notes that,

between the social body and its members everything can be reduced to a problem of distribution,”

whereas,

between two private persons, … everything boils down to some kind of exchange.”

Étienne Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas,

trans. Laurence K. Shook (Notre-Dame, Indiana:

University of Notre-Dame Press, 1956), 311

It is that difference (how to distribute justly, not unjustly favouring some people over others, and equality of exchange) that distinguishes the two species.

So we see that these are not really two kinds of justice (justice is one thing); what we have, rather, is two different situations in which to find the equality that defines justice. To identify what situation we are dealing with, in life, we could ask: In the treatment of particular people,

- is something being exchanged between two people;

- or is something being distributed (an act that could be an injustice to a third party: it is that person who should have received the distributed thing)?

A PUZZLE

Skinner argues that, despite being labelled DISTRIBUTIVA (again, is it a label?), what appears on the left has no connection with Aristotle’s discussion of that issue.

Further puzzles arise in the case of the actions illustrated under the heading [dis]tributiva. Again we see an angel with two kneeling figures. The one on the right, who holds a palm of glory, is being crowned; the one on the left, whose weapon lies beside him, is being decapitated by the angel with a sword. The main difficulty here is that neither in the Nicomachean Ethics, nor in Aristotle’s later analysis in the Politics, nor in any of Aquinas’s comments on either of these texts is it ever suggested that Aristotle’s concept of iustum [justice] distributivum is in any way connected with the infliction of punishment…. At no point is the issue of punitive justice ever raised.”

Skinner, “The Artist as Political Philosopher,” 38

But this objection can be answered, because punitive justice is raised, as Gilson directly shows, in connection with the term written out on the other side of the image! This is indeed puzzling – but let us see Gilson’s remarks on commutative justice.

COMMUTATIVE JUSTICE, OR JUSTICE PERSON-TO-PERSON

In relations between individuals

the gravest [wrongs] are those which consist in taking without giving anything in return. The gravest of all breaches of justice is to take someone’s life, because loss of life involves the loss of everything else as well.”

Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 313

Thus we do see on the left of this image of Justice an ‘injustice of exchange’. I fully grant you that we do not think of murder in terms of exchange, or, to be clearer, as exchange gone wrong. Gilson’s point here is that in murder, being injustice, there is indeed no exchange (it is taking without giving anything in return) – but just acts do have reciprocity, and this it is easier to see. That is, these are acts in which we give people what they are due. If in this situation there is not an exchange (– if, I say), there is nevertheless something that ought to be given, and that thing is recognition … as

one who is … our associate and brother.”

Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 313

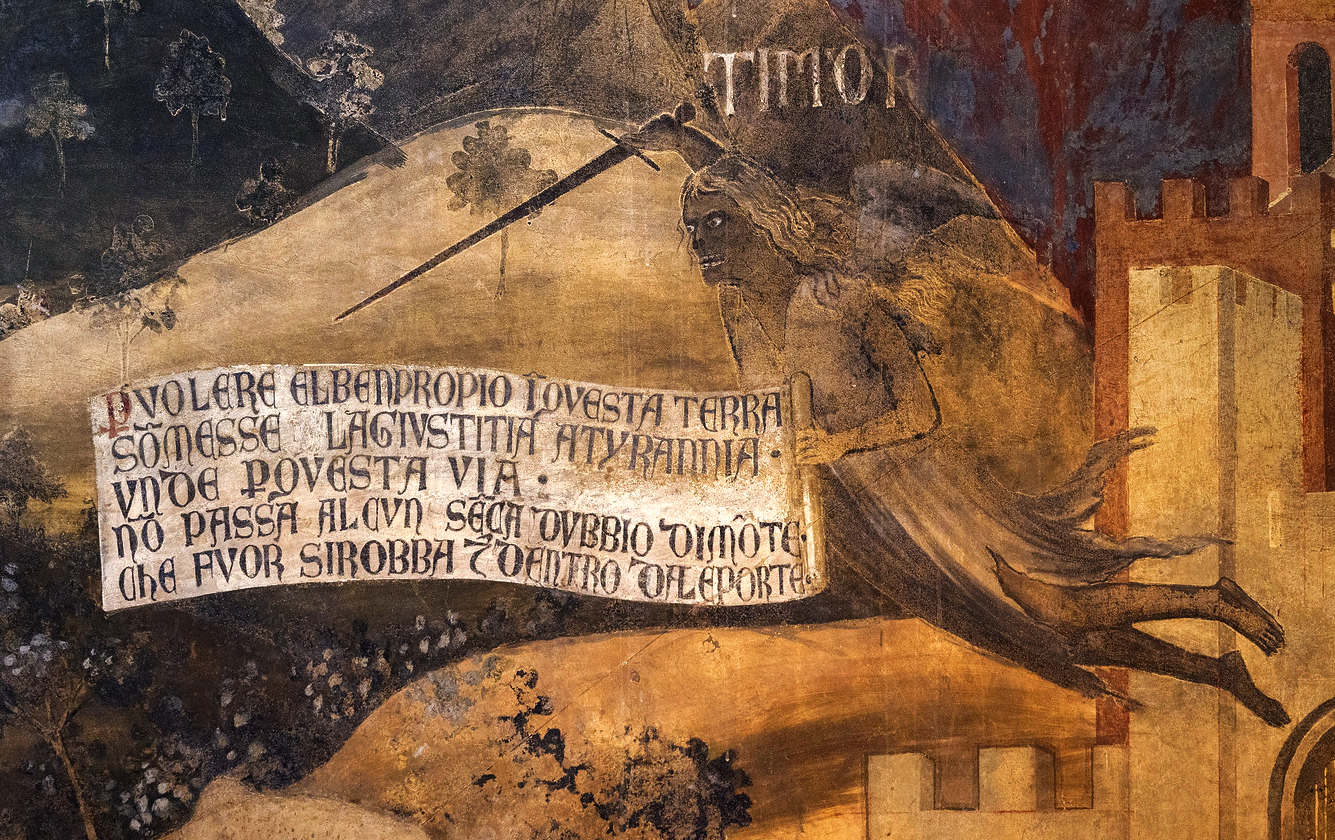

A person might come to believe that his life is being ruined by the people he then murders, but such a person has come to think about his situation according to that magic formula of evil “ELBENPROPIO” – ‘the good’ (elben) of the ‘self’ (propio), the principle we saw blazoned

on the wall of terror. “Each seeks only his own good”! In proceeding thus, the murderer commits a grave error in the way he thinks about people, supposing that people are individuals. The murderer is a person who has begun to act as an individual, “seek[ing] only his own good”, among other individuals doing the same thing, when that is not what we are.

on the wall of terror. “Each seeks only his own good”! In proceeding thus, the murderer commits a grave error in the way he thinks about people, supposing that people are individuals. The murderer is a person who has begun to act as an individual, “seek[ing] only his own good”, among other individuals doing the same thing, when that is not what we are.

In any given society individuals are only parts of the whole.”

Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 313

Do not read this to say that the whole at issue is a society or a community or a corporate body or a tribe or clan: that was not its meaning here – in a Siena binding itself, in this image, to Wisdom. This “whole” is rather a body of divinely made people, and that person – the murderer … and likewise the robber, the cheat, the liar, the slanderer, and all the other agents of injustice – does not give the other person his or her due, AS such a being.

To give them their due would be justice – the balance that is the mark of justice is struck when the degree of respect that a person is due is matched by the behaviour that is duly respectful.

At just this point the fresco begs us to recall that on that disturbing western wall we had indeed encountered Justice.

The figure of Justice, who is distinguished [there] by her legend and by her black and white robes, lies prostrate on the earth, her scales broken, at the feet of the diabolical tyrant. Around her we see the effects of her captivity: a girl is stabbed by a soldier, in the city another is seized by two men (yet another girl is on the ground).”

Chiara Frugoni, “The Book of Wisdom & Lorenzetti’s Fresco

in the Palazzo Pubblico at Siena,”

Journal of the Warburg & Courtauld Institutes 43 (1980), 241

– It may still seem, to us, that ‘exchange’ is not the right concept for person-to-person treatment, but (without going into this further) I would like to offer one thought to the contrary.

Simply in being creatures made in the image of God, human beings so made do give something to others, though others perhaps do not see this, or do not receive it, … and thus do not ‘give back what is due’, in exchange. People are giving to others by their being, despite handing nothing over in a market sense. Our notion of ‘exchange’ may have been corrupted somewhat by the paradigm of commerce, severing the inner connection of ‘exchange’ with reciprocity. (Was it severed to the same degree in 1340?)

DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE, OR JUSTICE SOCIETY-TO-PERSON

We must take account of the second region of justice.

What is justice itself? What we have thus far seen in the Room of the Nine is what we see throughout the medieval West – it is visible too in Giotto’s image of Justice, painted in 1306 for the Arena Chapel in Padua. Used in connection with Justice, the image of the balance signals the assertion that just acts are acts of balance, in which one thing is equally matched to another – but the Biblical term is not equality but ‘equity’.

What is justice itself? What we have thus far seen in the Room of the Nine is what we see throughout the medieval West – it is visible too in Giotto’s image of Justice, painted in 1306 for the Arena Chapel in Padua. Used in connection with Justice, the image of the balance signals the assertion that just acts are acts of balance, in which one thing is equally matched to another – but the Biblical term is not equality but ‘equity’.

While equality suggests an arithmetic equivalence, equity suggests what Gilson calls geometric proportionality (a contrast marked by Aristotle): we may be able to see, by eye – by putting one thing up beside the other – that two things are equal, but what is instead in the right proportion must be judged.

Discussing the “shoot from the stump of Jesse” upon which “the Spirit of the LORD shall rest”, Isaiah mentions “the Spirit of wisdom and understanding” that governs his judgement.

He shall not judge by what his eyes see … but with righteousness he shall judge the poor, and decide with equity for the meek of the earth;….”

Isaiah 11:1–4 ESV

To “decide with equity” is not to distribute equally to all but rather to give to each what is due, to give what is proportionate. (From this thinking we get another key Biblical concept: the notion of “my portion”.)

As for how the critical balance that defines justice is to be found, Gilson writes this.

These relationships are not based upon an arithmetic equality but rather, according to Aristotle, on a geometric proportion. Hence it is natural that some should receive more than others, since the distribution of advantages is carried out according to rank. When each, according to his place, receives in proportion to the rest, justice is done and rights [are] respected.”

Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 311–12

And this too marks a signal difference between the two types of justice. Commutative justice is found differently.

In exchanges between persons these problems are rather different. … Here it is a matter of so adjusting transactions that each gives or receives in proportion as he receives or gives. And so [in the relations under commutative justice] we have to reach an arithmetic equality where both parties end up with as much as they started with. Whether the end which justice seeks to establish be proportional [to varying merit] or arithmetic relationship [what is given receives its exact due], it is always a relationship of equality.”

Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 312

In some situations we look for strict equality (the punishment matched to the crime should, we think, be equal), but in other situations that sort of equivalence eludes us; we have to judge. An appointment (someone is to be awarded the role of a function within the state, the army, or a school); that benefit should be proportionate … to the particular proficiency and gifts of the candidate. These are the two kinds of equality signalled by the ‘balance’ image of justice.

INEQUALITY AMONG PEOPLE

Further, justice being the concern of what is due to people, we are compelled, says Gilson, to take account of the fact that in a society people are both equal (in some respects) and not equal in others. A child and an adult are equally made in the image of God, and on that account are owed the very same in the way they are treated (as we have just discussed under commutative justice). But a child is not equal to his parent in power, knowledge, and responsibility, and Gilson marks this aspect of inequality as differentiating the sphere of distributive justice.

When seeking to calculate or judge what is owed, you must often ask, What is owed to my father in that he is my father? Unlike the situation examined under commutative justice, you and the other person are not alike and not equal in what is owed you.

When the State wishes to distribute among its members [some] part of the community’s goods …, it takes into account the place occupied by each of these [members, who are] parts in the whole. Now these places are not equal, for each society has a hierarchical structure and it is of the very essence of the organized body politic that all of its members be not of the same rank.”

Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 312

There is no state of perfect equals.

It is like this under all regimes. In an aristocratic state classes are distinguished by worth and virtue; in an oligarchy wealth replaces nobility; in a democracy it is … the liberties enjoyed which arrange the members of the nation into a hierarchical order.”

In our present-day democracies (if that is what they are) we see just this kind of hierarchical ordering, in announcements of who ‘need not apply’ for various positions of employment.

In all cases … each person’s advantages are in proportion to the rank arising from his nobility, wealth, or the rights he has been able to win.”

Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 312

Before we close the discussion of this sphere of justice it seems quite important to see that there is a political, a republican, issue here.

FRAUDULENT JUSTICE, OR, THE REPUBLICAN FACTOR

We should at this point remember that the painting we are examining is the ‘political theory’ of a republic, and that in our present discussion we are looking at a republic’s conception of justice. We ought then to appreciate is that in the Republic of Siena we are seeing a rejection of the way that distributive justice operates in aristocracies, oligarchies, and democracies (exactly what Gilson has just sketched).

In a democracy, Gilson said, various sub-groups “win” particular “rights” (a privilege not accorded to other groups), according to which the government then distributes goods. The same sort of thing occurs under aristocracies and oligarchies, which esteem, respectively, the aristocratic and the wealthy classes more highly. In all these cases we are talking about how the members of these groups are to be ranked in the distribution of offices and goods. As Skinner explains, commenting on Aristotle,

in book V of the Ethics the problem with which he is alone concerned in asking what constitutes ‘iustitia’ in relation to ‘distributionibus’ is that of discovering a rule of fairness for the allocation of scarce and valued resources. The examples he offers … are money and honours, and the celebrated thesis he defends is that the appropriate rule to follow must be to distribute them ‘secundum dignitatem’ or according to worth.”

Skinner, “The Artist as Political Philosopher,” 38

But there are different estimations of worth.

A republic re-orders – that is corrects – assessments of worth in its own way. A republic is a de facto condemnation of the other forms of government as unjust regimes that attach false verdicts of worth to particular kinds of status or identity. In the Room of the Nine we should not lose sight of this. Every government promises justice, but each government can render only the justice of its form of government (applying the aristocrat’s assessment of merit or worth, or the oligarch’s, the democrat’s, the socialist’s).

Apply this, if you would, to news of the moment. The oligarch wants his business to be successful; does he then say that the entry-level

foreign worker deserves a visa, … deserves to work in America for a lower wage than the citizen worker, for the good of business success? – Is that not the justice of the oligarch, and is it justice? – In moving through Lorenzetti’s image we must keep our eyes open for anything that says No, that is injustice. A republic will set up another and different measure of justice, directing the citizen of the republic to another way of calculating merit, using a true standard. (We have already seen that standard announced by the place accorded, in the Room of the Nine and in the room preceding it, to the Book of Wisdom and all that it stands for:

• that one apocryphal book,

• the Old and New Testaments,

• Jesus as the “shoot from the stump of Jesse” on which the “Spirit of wisdom and understanding” has rested,

• the people and their tradition: thinkers, writers, governors, townspeople and countrymen who are conformed to his example, this thinking and behaviour.)

5 | Summation of justice

It is a little surprising that in the imagery on this wall that we have examined thus far, there has been so much to discuss, an amount only compounded by our detour into philosophy. That is not exactly a detour, however, if it is the texts of the painting itself that sent us down that path. Our objective from the start has been to see what the walls of this room – containing texts and imagery – have to teach both 14th-century townspeople and viewers today. Perhaps the first lesson for us is that our conception of justice is naively simple. We work with unjustified assumptions about both what justice is and whose concern it is.

Lorenzetti’s fresco teaches, in accord with Scripture, the centrality of justice to governance.

Justice, and only justice, you shall follow, that you may live and inherit the land that the LORD your God is giving you.”

Deuteronomy 16:20 ESV

Let’s sum up Siena’s presentation of justice.

Lorenzetti’s image tells us, as it told the people of Siena, that all justice involves equity: in human interactions what is given must be matched to he to whom it is given and what it is given for. Further, this mark is to be hit in two kinds of relation: person to person and group to person. But we must agree with Starn and Partridge that that distinction does not make it into the imagery: with respect to these two species of justice, the distributive sort involving

the fair distribution of goods [in] the community as a whole, whereas commutative justice involved only exchanges between individuals of equal standing – [we have] a difference [that] the frescoes hardly make clear.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 44

Yet it is there on the wall, in the work – through its text.

How do we resolve that puzzle of the ‘labels’ (that under the motto DISTRIBUTIVA we are not given an illustration of that species of justice)? One scholar suggests that the labels are in the wrong places and should be swapped! The problems encountered

oblige us without equivocation to transpose to the left … the epigraph appearing on the right (COMUTATIVA) and the one on the left to the right (DISTRIBUTIVA): it is immaterial whether the present arrangement results from a mistaken restoration that altered the original layout, or an error by the artist himself, which is far from being out of the question….”

Frugoni, A Distant City, 191

But I do not think this solves the problem. Switch the labels if you wish, but on the right side we will still not have a clear illustration of society-to-person distribution (it is not easy to see how the figures with box and spears exemplify the just distribution of resources). – So you decide!

(Should it interest you to consider an opinion, here is mine. To me it seems that the Latin terms do not label the images. We have two dualities: one evident in the image [apparent to all] and another indicated by the Latin [of which the learned are simply reminded]. To the objection ‘How do we know that one angel is giving, the other receiving, when the gesture is identical?’ my response is that, in a still image these opposite gestures are identical in reality, so we might be seeing either one – the gesture itself will not be the clincher. The gesture is like a homonymous word in a sentence – identical letters with two different meanings – a word whose meaning is settled by the sense you can make of the whole.

(Indeed, try this on for size. The angel on the right is both giving and receiving. That is the import of the verse of Deuteronomy that I quoted to explain the justness of giving, to God, what is our own property: that wealth and property came to us (the angel giving) because of a divine gift of powers; thus we should give it back, or give back a just proportion (the angel receiving). The receiving angel is a stand-in for Siena, enacting, as other rulers had done, divine justice, operating as a godly city.

So David reigned over all Israel. And David administered justice and equity to all his people.”

2 Samuel 8:15 ESV

(As for those godly projects, note that roughly a century earlier

the Spedale (hospital) of Santa Maria della Scala was detached from the control of the cathedral clergy and taken over by the city.”

Jane Stevenson, Siena: the Life and Afterlife of a Medieval City

(London: Head of Zeus, 2022), ch. 3

(The commune then acquired the right to collect money for the hospital. Indeed, take note of the nature of this civic project.

By the fourteenth century, after the commune itself, the hospital was the most important corporate body in Siena. The wealth it acquired was invested in land, and by the fourteenth century it owned enormous amounts of the Sienese countryside and was a major supplier of wheat to the city.

Stevenson, Siena: the Life and Afterlife of a Medieval City, ch. 3

(To what end was the hospital both a service to the ill and a source of bodily sustenance to the well? To the glory of God.

(Before we leave this angel on the right side of the scales, the giving angel may indeed be a stand-in for Siena, a city that has made itself an instrument of God. Imagine that you are a person who is given the care you need in the Spedale of Santa Maria.– Opinion-giving concluded.)

Continuing our summary, to attain justice it is essential, first, to discern what is just, and this involves a connection to Wisdom. No presumptive sense of justice can be trusted. What that ‘connection to Wisdom’ is, the fresco does not explore, but there is general clarity given the five-point meaning of wisdom that we outlined above at the close of section 4.

But justice is not a matter of verdicts, or values. The intention announced in this fresco is to spare Siena from the injustice depicted in all its horror on the room’s west wall. For that to happen the balance that we discern through Wisdom must also be struck: realized in human interactions. Look here at the hands of Justice.

They are on the scales. Literally, Justice has her thumbs on the scales.

Our reflex thought is sure to be that this is interference in the weighing; to ‘put a thumb on the scales’ is virtually our only scales idiom, and for us it has only one meaning. But what Justice is interfering in is the self-interest we saw run rampant on that wall of misery. It is necessary not just to find the mark of equity, in this relation or that, but to actually give what the other is owed, and indeed to be able to do so. That means to arrange things so that this can be done. We saw an example of exactly that behaviour in the running of the hospital.

If it is considered just that the townspeople receive the care that a hospital delivers, then it is necessary to arrange things so that that care could be given (necessary to staff and equip the hospital). That is just what the Sienese did in making the hospital “the most important corporate body in Siena” after the commune itself. (Whereas the hospital in my town seems the last thing the governors of my state seem to care about.) Siena not only prioritized that institution but ran its hospital like a business-generator-of-justice (investing in farmland so as to ensure a supply of bread for the entire city). It was an institution yoked to what the people are due.

This is the right point at which to note one last detail of Lorenzetti’s picture of justice. Note the two cords that run downward from each of the pans – one red (which we might interpret as the colour of flesh and blood), one white (the colour of purity or spirit).

In fact we have already identified them, as they control the balance of the two pans that have a dual meaning: that is, the pans, and the cords that can control them from below, represent a duality of dualities. Exactly as the hands of Justice do, the two cords secure:

- person-to-person justice

- society-to-person justice

and also

- justice in receiving (a concern that we, people, receive our due), and

- justice in giving (a concern that God receives His due).

Their full significance becomes apparent as soon as we see where the two cords run.

Both cords come together in the hand of a further personification almost as large as Justice, a figure dressed in grey with gold brocade like that worn by Justice. She is labelled CONCORDIA (the pun on ‘cord’ fully intended).  But the cords do not end there: they pass through her hand to the hand of a citizen, who takes hold of the twisted red-and-white strand.

But the cords do not end there: they pass through her hand to the hand of a citizen, who takes hold of the twisted red-and-white strand.

Indeed, as we we shall see when we conclude our examination of Lorenzetti’s image of politics, that cord extends visibly through the crowd of Sienese countrymen lined up to the right of Concordia. How far this power to create justice runs, and what else it relies upon, we shall see when we continue.

NEXT:

• THE COURT OF CONCORD

• THE WALL OF GLORY – OR, MAKING SIENA GREAT AGAIN: JOY IN THE GLORY OF THE FLOURISHING CITY

Artist

Ambrogio Lorenzetti (active 1319–1347)

Date

1337–1340

Still in its original site in the Room of the Nine (Sala dei Novi) of the Palazzo Pubblico Comunale, Siena

Medium

Fresco

Photo credit

Steven Zucker, Smarthistory