Dropping Fatal Baggage (‘Equipment’ from the Enemy)

On the Proposal That the Culture Is Not Collapsing, It Is Gone | Part 6

Some will refuse to consider the hypothesis that our culture has gone because they are remaining positive. Allow me to give this objector a full chance to speak his piece, for just a moment.

Why should we explore an hypothesis that means that we are beaten? If you find out that your hypothesis is false, then it was pointless to look into it, and if you find out that it is correct, then … we are beaten, so it was pointless to look into it.

But as a matter of fact we are not beaten, we can never be beaten, which renders your very hypothesis false from the start. There is something in the human spirit that cannot be annihilated.

People who are ‘positive’ in this way, who turn from dark prospects because they are ‘being positive’ and hopeful, are not to be trusted, and what is wrong with them is their negativity.

First, being positive matters, and this is a person who starts by handing you a counterfeit positivity. What is truly positive, not just cosmetically or theatrically positive, is to examine reality – not diving for shelter into a sheer presumption. Who says that to lose our culture means that we are beaten? The thing this hopeful Harry is reacting against is the ‘beaten’ component (and underestimating the human spirit), but all that is entirely Harry’s contribution.

Why should seeing that we have let our culture slip away not be our one hope – this being like spotting the life raft that we could swim to?

Why should we be beaten when we see that we have let our culture go? I suppose it is a possibility, that to lose your culture is to be finished (trampled by history, thrown on the waste heap), but how can we talk about what it means to lose a culture before we have cared to discuss what a loss of culture is? – Ah, but this is the thing that Harry is too hopeful to do.

[]

I put it to you, however, that the risk of being beaten lies with cheerfully believing in our culture no matter how dark things look, as the logic of this has you ‘believing in your culture’ past the point of having a culture, when the thing is gone. Once you have turned into this kind of believer you are one of the people who has ceased to care about your culture: the rumour of it is enough.

But truly the situation is worse than that: your belief in it has replaced it … as well as rumours. This ‘believer in the culture’ is a person who, because he believes, will not lift a finger to get it back.

We should take care to note, by the way, the revealing phrasing of that objection. Any person who asks,

Don’t you believe in your culture?

(believe in it so much as to dismiss the question of loss of culture) is in fact telling you that a people survives on belief, not culture. All talk of ‘belief in’ your culture is a habit of anti-culture, of disdain for culture: if you only believe, your culture will be there. But culture is an actual thing that is there only in cultural activity.

Everything that we have learned about faith, by the way, helps us dissolve this question, which is not in fact a question but a charge of faithlessness, ‘weakness of belief’. If you have had a proper training in faith you will easily exorcise that charge, for its demonic falsity. Suppose we agree that belief is essential; well, belief without works is dead. That person has no ‘belief in our culture’ whose life is not lived in the forms that our culture developed to make us and sustain us as the people we are.

You believe ‘in your culture’ (banishing all magical thinking with a sign of the cross) only when the culture you believe in is there, where it ought to be – or when you pray and work for its return, because it is not there, and you miss it.

This is the urgency behind our asking about the state of this culture (are the statues standing, or in ruins?).

[]

So the thesis I am proposing does not involve, simply, hypothesizing about the loss of our culture; it involves attention paid to the actual character of our culture: the effort to identify what that culture is, so that we could go to those institutions and see whether they are occupied – whether they have us in them, working the machinery, delivering the aid, ‘edifying’ ourselves.

Before you can assess the state of a thing – a thing that is, in sum, the vehicle of our life – you have to think about just what is the vehicle of that life.

And doing that will free us of another item of baggage that does not belong to us, an attachment that is another element in the overthrow or collapse of a culture. This is preoccupation with business that is not ours. Get a person carrying the bags you hand him and you keep his hands off the handles of his own business. So another fatal distraction is, so to speak, What the Persian is doing. The ancient Athenian did not care; it was not relevant.

(Clearly we need a footnote here, to register a ‘but’. It was not relevant because Persia was elsewhere, was an entirely different land, and this is not our situation. We will need a name for the phenomenon that I noted in section 3: the historical event of the emergence within a single land of two cultures, two peoples. (Something unprecedented? Perhaps, but perhaps not. The emergence of Christian culture and Christendom within the Roman empire, indeed at the centre of the Roman empire, seems in some ways comparable; we shall have to see.)

But the suggestion, further to that ‘but’, that two peoples forced together in one boundary, one suit of clothes, have to care about what the other is doing (in the one way I am discussing) may still be a great mistake.

Imagine that somehow Athenians and Persians were thrown together within a single boundary. The Athenian’s knowledge that the Persian is what he calls ‘a barbarian’ (and vice versa) is a strength that frees him to do what I noted above: to live in the forms that his culture developed so as to give the world the Athenian and keep this people living.

I read quite recently that a prominent observer of our situation has said that “gender ideology” is the great threat to the West today (I have forgotten where I read this, likely in a comment to some article). I have not bothered to verify the claim as I doubt this man can be so mistaken. Gender ideology is the business of – and I say this in the kindest of ways – the ‘barbarian’ culture.

Anyone who thinks that the fate of the West lies in the hands of its opponents has badly misjudged what the death of the West looks like. The definitive loser of the culture war is the side that both has no culture by which to perpetuate itself, and either refuses to see this or sees this when the hour is too late – when the opportunity for restoring that culture has passed, because too many conservatives are really happier with the replacement culture that has handed them their animating beliefs.

A few years ago Rusty Reno reflected on this issue, referring to some remarks made in 1955 by German novelist and essayist Ernst Jünger. It might be too late; it might be that now

we have … no basis on which and from which to reconstitute our dissolved world…. Today it can seem that our inheritance … exists only in nostalgic dreams…. All is lost,….

Then Reno adds,

But that is not true.

R.R. Reno, Afterword, Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West (Simon and Schuster, 2019)

In support of Reno’s verdict I can add one thing that we know with absolute certainty, which is that we are in no position to assess the fate of our culture when we have scarcely begun to look at the very possibility of the fall of a culture – and at the actual causal chain of such a fall. For the fact is that the cause of such a collapse will always be more than the action of the destroyer. The fall of a culture may require a destroyer, but as in any revolution the destroyer has to hit a target, with devastating power, and in a cultural revolution that target is your will to live by the ways of your culture.

In Return of the Strong Gods Reno directs us to a very powerful influence: the 20th-century story that emerged after the catastrophes of two World Wars (both originating in the West) warning us of the greatest evil still threatening us: we could repeat the horrors (but there is a way to leap ahead and escape the old forces that caused them). What is brilliant about Reno’s treatment of our present decay is his proposal concerning its cause. This move in the destruction of a culture did not take the shape of an assault on culture at all; it came as an impassioned argument for a goal we were all agreed on; it was a humanitarian project (with fine print about the means, the cultural liabilities that put everything human at risk).

In Reno’s account we have a beautiful illustration of both a force that found its critical target (in our will) and the omission on our part that made it deadly. This was an assault that exploited a weakness within us, and the value of Reno’s form of account is that it contains lessons about weakness that we can learn. The premise of what was in fact a ‘humanitarian’ assault on Western culture –

that the traumas of the first half of the 20th century fundamentally altered the conditions of human existence,

Reno, Afterword, Return of the Strong Gods

– was a premise easily dismissed by any people immersed not in immediacy but in history. We can see in retrospect one kind of crack in the foundation that threatens the entire structure of our society.

[]

My suggestion, in this last introductory segment on cultural revolution, is that attention to this hypothesis is truly positive. It is the Athenian who matters in the story of Athenian culture: it is his or her preoccupations, reflection, self-examination that determine what is too late. The ‘enemy’ in the title above is indeed the opponent of your culture, but this is not at all the member of an opposing culture, whom I have said cannot end your culture. All he can do is work on you, appealing to something in you that might betray it. The enemy is the demonic spirit behind tragedy, to whom we can say yes.

Yet it may be that many are, ever so gradually, awakening to the actual drama concerning our culture: it is not over the fence, in the yard of those who have rejected it. Here we can call on some Persian wisdom, in the original fable of the scorpion who asks to be ferried across the river, by … not the frog (who is stung and dies) but the turtle (who is likewise stung, but is protected, by his own nature, from the nature of his foe). A paraphrase of the moral, applied to our situation:

Truly have the sages said that to trust that the scorpion will be other than a scorpion is to give one’s honour to the wind and to shame one’s own self.

There are signs of this wisdom around us. On the day of the recent U.S. mid-term election, Jeremy Boreing of the Daily Wire moved to correct a few supporters.

Some of our fans were talking this afternoon about the rise of ideas like transgenderism, … gay marriage, and they were saying we’re destroying our culture with these things, and I don’t actually think that that’s the accurate point of view. I think we are destroying our culture and these things are growing in some ways out of that destruction, the way that algae grows on a dirty aquarium. – The algae doesn’t make the aquarium dirty; the algae is a reaction to how dirty the aquarium is.

The Daily Wire Election Night 2022 (8 November 2022)

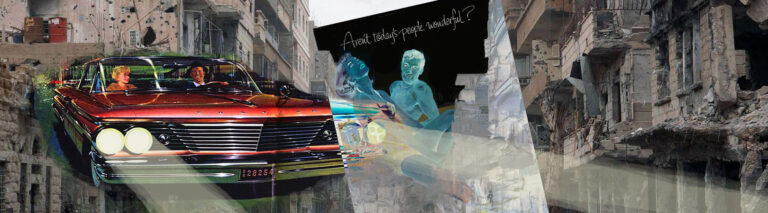

Excellent. Boreing says we “are destroying our culture,” present tense. This is as close as we dare come to the truth but it is still a major step, if one step short of recognizing that we are living in someone else’s culture, because ours has been broken up and carted away.

It is utterly astonishing that we display that particular blindness that is to ignore the remains of a treasure that we alone were equipped to honour, a culture that we alone built, and, standing on the broken faces of shattered statues, instead gape in fury at what the ‘barbarians’ are constructing. It is only what they do that stirs our blood. – Can a culture be destroyed? If this is its condition the answer is obvious. This is all the evidence that is needed of a people that has lost its own culture.

[]

The collapse of Western culture is a ‘world-historical event’ on the scale of the collapse of pagan culture. We must consider the hypothesis that our own countries were the scene of the rise of a new people that accomplished, through the will of the Western people who were dominant, the successful elimination of that longstanding and dominant culture. This is the collapse of a culture effectively overhauled by an ‘inheritor’ who equated it, at its heart, with evil.

That was the thinking of the Christians who overthrew pagan culture at the end of the fourth century, but it is more urgent for us to know that it has happened again … that there has been a kind of revolution from the margins of a dominant culture that has dismantled the reigning culture and replaced it with its antithesis.

To see this may require a careful comparison of our age with that earlier age of cultural destruction, even though there are bound to be notable differences between the two events. Still more, the full picture will have to include answers to all of the following.

- What does it mean to possess or to lose a culture?

- How was the past [blank] number of years the term of an accomplished revolution? – What are the phases of that bloodless overthrow, and what is that number? Fifty years, a century (running back to 1918), two-hundred years?

- On what terms does a people hold its culture? Is it not the case that every actual people possesses a culture of its own, for which it does not apologize? (Do we not see this confidence in that ‘people’ that has delivered the prevailing culture?)

- Could it be that every person who participates in a society adopts the culture that that society (knowingly or otherwise) incarnates? So that to lose one culture is not in fact to be without culture but rather to live by another?

- Who is the ‘we’ whose culture has been lost?

- How could our culture be gone when we have our ways, all those ways that are hated by the other side?

- And how could Christians ever lose their culture? If life in the Church (which Christians in fact constitute) is the culture of Christians, the Church has not been demolished – so how could any talk of a demolished culture apply to Christians?

- And at the mention of Christianity, what does love (specifically love of neighbour) require? If you are to deny yourself (Luke 9:23) out of love for your neighbour you are not, says the Gospel, denying your life but winning it (verse 24). What, then, are we to deny ourselves: material goods? spiritual goods? acting to secure the good of fellow citizens, of our offspring – denied because this would be to decide things our way? In terms of these material and spiritual goods, whose way, then, is to count for us, acting with love? – How do we think about this; what is the precise category of what we must renounce, in loving those unlike us?

(I know that I will continue to think about these things, and to do that thinking I will have to write those thoughts out … until I have the sense of getting somewhere. In a sense, I would rather not, as I have other things that I need to do. But there is the pressure of a sense of obligation to be in this time, as a person with a mind.)