Individual beauty | Thutmose’s Nefertiti

As this is a long read, a summary may help you decide whether to wade in.

• HOW IT WAS UNDERSTOOD LONG AGO THAT THE BEAUTY IN THE WORLD IS BOTH CONFORMITY WITH DIVINE BEAUTY & INCLUDES INDIVIDUAL BEAUTY.

THAT IS, THE UNIQUE CREATURE MADE BY GOD IS NOT JUST THE SAME, IN ITS BEAUTY, AS EVERY OTHER CREATURE (AS PER THE TITLE OF THE SACRED SONG “TO HIM WE ARE ALL THE SAME”, ON GALATIANS 3:28 ) BUT UNIQUELY BEAUTIFUL. (ALL THE SAME IN ONE SENSE BUT NOT IN ANOTHER.)

• & HOW MODERN CHRISTIANS ADOPTED A NIHILISTIC VIEW OF THE WORLD WHEN THEY BEGAN TO CLAIM THAT NO SORT OF DIRECTION IS GIVEN BY ‘PARTICULARS’.

• PLUS A LOOK AT THE MODERN CONCEPTION OF ‘THE INDIVIDUAL’ | THE BARRIER IMPOSED ON HISTORICAL KNOWLEDGE BY LIBERALISM, IN ITS EXCLUSION OF TRUTH | & THE PRICE OF BEAUTIFUL CITIES

1 | Individuality & the ‘first individual’

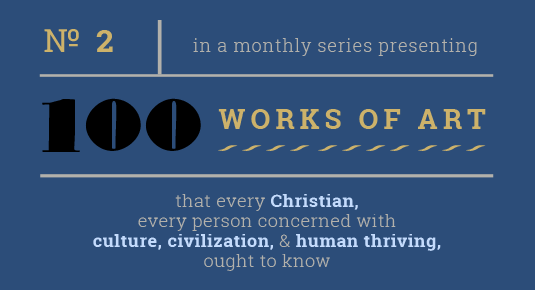

Writers writing about Akhenaten – or Ikhnaton (there are different ways to transliterate ancient Egyptian) – the rebel pharaoh of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty, seem to like mentioning that he has been called “the first individual in history”. But rarely do they say where this judgement came from or what was meant by the scholar who proposed it. Repeated in that manner, as a label, this is a factoid – a ‘fact’ that gives your own fantasy about its meaning the suggestion of truth.

Writers writing about Akhenaten – or Ikhnaton (there are different ways to transliterate ancient Egyptian) – the rebel pharaoh of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty, seem to like mentioning that he has been called “the first individual in history”. But rarely do they say where this judgement came from or what was meant by the scholar who proposed it. Repeated in that manner, as a label, this is a factoid – a ‘fact’ that gives your own fantasy about its meaning the suggestion of truth.

There is something true here: this was said, by an Egyptologist – but since the reason for saying it is omitted the factoid is just an opening for whatever meaning a reader wishes to insert here. Many people are strangely disinclined to ask, ‘But what does this mean, the first individual ?’, far more inclined to imagine they know. I was about to say that moulding factoids to the shape of your own mind does not give you knowledge of history (what is ‘historical’ about projections?) but was stopped by the thought of just how many people might not care about this, since they do not conceive of history as truth about the past. History is just one more canvas on which to spill your own contents, one more peg on which to hang an identity.

The factoid about Akhenaten (stripped as it is of detail) encourages the reader who is handed it to think that his or her contemporary ideas about ‘the individual’ find a champion in ancient Egypt. People like the sound of the first individual in history – which tells us that the individual emerges in historical time, that once there were no such creatures, and that individuality is the achievement of an act of human will. Only none of this is true. In this supposed ‘Age of the Individual’ we have a surprisingly poor grasp of the concept.

Individuality is a work of God. We are individuals from the moment of birth, owing to no initiative on our part. God makes individuals, and, something even more surprising, even creates individual beauty.

2 | How can there be order in individuality?

When Augustine writes

“everything is beautiful that is in due order”

Augustine, Of True Religion, 41.77

this prompts in some minds the thought that there is a general principle of order that explains beauty. When the material of, say, a sculpture conforms to this order, it is beautiful. Beauty lies in this ‘rising to the level of a higher principle’ and is thus a kind of ‘escape from individuality’ (a degraded state in being unconformed to this law).

But in the expression general principle the word ‘general’ means ‘of a genus’ – of a class or kind, and an individual is exactly not a kind, rather a member of a kind, in the way the individual thing possesses the defining features of the class. (MORE ON THIS HERE IF WANTED) Thus things may be good, even beautiful, in that conformity: in the way they “do their work” (quoting from the “Great Hymn to Aten” that is attributed to Akhenaten), the work of their kind.

All cattle rest upon their herbage,

All trees and plants flourish,

The birds flutter in their marshes,

Their wings uplifted in adoration to thee.

All the sheep dance upon their feet,

All winged things fly,….

Hymn to Aten, in James Henry Breasted,

The Development of Religion & Thought in Ancient Egypt

(London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1912), 372–73

But if that is what beauty is, if things are beautiful in being successful and functioning exemplars of their kind, then there is no individual beauty. A thing that has individuality, while possessing the defining traits of its kind, has individual characteristics superadded onto its generic features. And how can a unique thing have a “due order”? If beauty is a kind of order, how can a thing be beautiful in its individuality? – Yet it can.

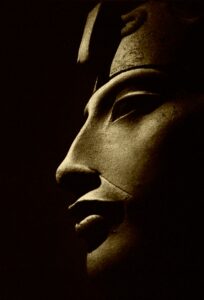

The beauty of Nefertiti, wife of Akhenaten, is not generic beauty; it is the beauty of an individual.

The beauty of Nefertiti, wife of Akhenaten, is not generic beauty; it is the beauty of an individual.

People are tempted to say that beauty is rational, conformity to some general, knowable order, as Augustine often seems to suggest:

Examine the beauty of bodily form, and you will find that everything is in its place by number

Augustine, De Libero

Arbitrio, 2.16.42

– beauty, he says, proceeds from proportion, order, unity. But one scholar tells us that

Augustine did not fall into the error of reducing all the aesthetic constituents to formal numerical relations, the kind of reduction which has tempted those who have tried to find in art geometrical laws, the golden section, etc.

Emmanuel Chapman, “Some Aspects of

St. Augustine’s Philosophy of Beauty,”

Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism

1:1 (1941), 49–50

Whether he is right about Augustine it is certain that beauty is far more mysterious than anything we think of as laws of beauty. God invests even the individual thing with its own beauty.

The Christian philosopher’s affirmation of an infinite God as the supreme reality did not diminish but brought out more sharply the reality of finite subjects each … possessing its own degrees of unity, truth, goodness, and beauty.… The infinite did not swallow up the finite, the necessary did not obliterate the contingent, the absolute did not eclipse relative beings, the spiritual did not negate the material. For the Christian thinker, matter was real and good, and so too [was] the body….

Chapman, “Some Aspects of St. Augustine’s

Philosophy of Beauty,” 47

The body: which, I am saying, is beautiful not solely in possessing the general form of the body (proportioned as bodies properly are) but also in its uniqueness, its distinctiveness: its ‘suchness’ altogether removed from any norm.

The face of Nefertiti is not ‘normal’. It is not a generic human face; it is an individual human face – that is to say, the unique face of a particular and individualized woman, a face distinct in its particular beauty from every other human face. – This woman is uniquely beautiful. In this work of art that is thirty-three hundred years old we see the individuality both created and loved by God.

Nefertiti’s face of course conforms to the norm of a human face in that it is a human face, but Nefertiti was not just ‘one more instance of humanity’. She was an individual, which is to say not just the exemplar of common and shareable qualities. The face presented to us in this plaster-coated limestone bust does not just exemplify the order laid down by God’s idea of a human face; in her particularity too she radiates the ‘principle’ (a divine principle) of beauty – where the ‘principle’ is some order to which the image conforms, something that is the cause of the beauty we see.

But this is no principle that we can formulate; it is simply not accessible to reason. How can a principle that can be set forth not be a general principle, and how can a general principle explain the perfection of something unique? It is as if each beautiful particular has its own unique order!

THE ‘PROBLEM’ WITH PARTICULARS

Everything is good, it is said, in that it tends to God, and particulars look to be at the furthest possible remove from God (whom we tend to conceive as, in Himself, the divine essence). Located at such an extreme distance from this, particularity has often been problematized by Christians. (But is God an essence? Isn’t God the great individual?)

Francis Schaeffer remarked that,

by particulars we mean the individual things which are about us; a chair is a particular,…. The individual person is also a particular and thus you are a particular.

Francis Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live?:

The Rise & Decline of Western Thought & Culture

(Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway, 1976), 52

And though particularity

And though particularity

is important because it has been created by God, and is not to be despised … (the things of the body are not to be despised when compared with the soul),

Schaeffer, Escape from Reason

(Downer’s Grove, Ill.:

InterVarsity, 1968), 10

a “basic problem” arises from attention to particulars, a serious problem that caught Schaeffer’s attention in this book on the decline of the West.

Beginning with man alone and only the individual things in the world (the particulars), the problem is how to find any ultimate and adequate meaning in the individual things. Without some ultimate meaning for a person (for me, an individual), what is the use of living…?

Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live?, 53

But the answer to this was given long ago – given even in Egypt, by a work of art. Schaeffer’s problem is eradicated by what Augustine calls

the eloquence of things : eloquentia rerum,

Augustine, The City of God, 11.18

to which ancient peoples were sensitive. When you find yourself in this world, immersed in particulars, you are never without a source of meaning (less than the “ultimate and adequate meaning” but a kind of glimpse or indication of it). When you are surrounded by individual human beings you are never “beginning with man alone”. The world, through its very form, speaks of what there is to live for. Things speak.

This was known long before Augustine and is implicit in the Hymn to the god Aten, in which Akhenaten honoured the divine presence in material things:

Thou makest the beauty of form, through thyself alone,

Cited by Breasted, Development of

Religion and Thought, 375

a thought akin to words of Augustine:

Father, who are the beauty of all beautiful things.

Augustine, Confessions, 3.6.10

That is, God is manifest in the beauty “of all beautiful things”, which include beautiful particulars, individually beautiful things. The “beauty of form” speaks of the source of beauty – or that law or norm or model of beauty in which the beautiful thing participates – but this is obviously not a formulable principle, as the ‘principle’ is God! Beauty reveals God, is a perception of God.

This is not pantheism: it is not that nature either is God or is inhabited by God, but that God is the creator of nature and forms it in such as way as to show himself in it. It is the beauty of God that ‘particulars’, matter ordered so as to be beautiful, show us, somehow participating in the nature of God.

THE BEAUTIFUL ONE

THE BEAUTIFUL ONE

The name Nefertiti means

the beautiful one has come.

For short, she was called Neferet,

the beauty.

John Darnell & Colleen Darnell,

Egypt’s Golden Couple: When Akhenaten

& Nefertiti Were Gods on Earth

(New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2022), 48, 50

It is thought that Nefertiti was a commoner, elevated by her beauty to the rank of a queen, in fact the Great Wife.

Nefertiti was not her husband’s only wife. Like all of Egypt’s kings, Akhenaten maintained a harem of secondary queens…. As ‘King’s Great Wife’, Nefertiti enjoyed a very different life from her co-wives. She lived in the palace, not the harem, where she was recognized as the mother in the nuclear royal family. She was the queen who, bearing the appropriate titles, crowns, and regalia, was represented in all official writings and artwork.

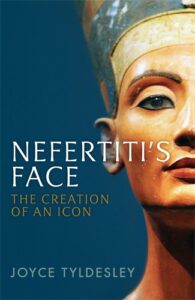

Joyce Tyldesley, Nefertiti’s Face: The Creation of

an Icon (London: Profile Books, 2018), 9–10

In the second year of his reign Akhenaten gave his wife an additional name, a name that explains what her beauty is and where it comes from.

Neferneferuaten : ‘Exquisite Beauty of the Aten’

Tyldesley, Nefertiti’s Face, 9

In the understanding of Akhenaten, then, the beauty of Nefertiti – and we see in this sculpture that it is the particular beauty of Nefertiti – speaks. Her form is eloquent, and it speaks of something supreme, which has bestowed on the world the beauty of this woman and of all created and finite things.

In the understanding of Akhenaten, then, the beauty of Nefertiti – and we see in this sculpture that it is the particular beauty of Nefertiti – speaks. Her form is eloquent, and it speaks of something supreme, which has bestowed on the world the beauty of this woman and of all created and finite things.

Nefertiti herself has vanished without a trace (Egyptologists have only unconfirmable theories about the fate of her presumably mummified body): but the form of her face, her particular beauty, remains.

In a recent book she titled Nefertiti’s Face Joyce Tyldesley asks,

In a recent book she titled Nefertiti’s Face Joyce Tyldesley asks,

Why is the Berlin Nefertiti so beautiful to so many of us, irrespective of age, gender, race or culture?

Tyldesley, Nefertiti’s Face, ch. 4

Enduringly beautiful after three thousand years. Schaeffer had spoken as if particulars were simply that – things presenting themselves, leaving us isolated, without answers to existential questions – but in that verdict he was out of step with the Hymn to Aten, with Augustine and many other medieval Christians, indeed with Scripture itself, which directly states that created things declare – speak of, in “speech” of their own – the glory/splendour/beauty of God (Psalm 19:1).

3 | The aloneness of the modern individual

We must look more closely at the head of Nefertiti in Berlin’s Egyptian Museum, one of the most famous works of art from all of ancient history, and do so to grasp its purpose, which was so much more than to ‘portray’ the queen. But it may be worth filling in, first, that blank concerning Akhenaten’s supposed ‘individuality’, because it allows us to flush out a ‘development’ from ‘the West’ that blinds us to the meaning of art.

To see works of art – see them as expressions of culture, as life-bearing creations – you really must grasp what has intervened, in the late-modern age, to take away your eyes and prevent you from seeing – so that you may tear off this blindfold.

The man who called Akhenaten

the first individual in human history

James Henry Breasted, A History of Egypt from

the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest

(New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905), 356

was James Henry Breasted, the first professor of Egyptology in the United States, a position Breasted assumed in 1905 in the year he made this claim.  What he meant by an individual is a person not directed by tradition, a rebel who rejects the tradition he grew up in. Another scholar echoed his meaning in calling Akhenaton

What he meant by an individual is a person not directed by tradition, a rebel who rejects the tradition he grew up in. Another scholar echoed his meaning in calling Akhenaton

[the] first rebel … whom we know, the first man with ideas of his own….

J.D.S. Pendlebury, Tell el-Amarna (London, 1935), xiv

But the whole thrust of this (entirely modern) conception of the individual is to isolate the individual as a person who is acting on his own. What we are given by these scholars is an atheistic narration of history, a view of things that is very far from Akhenaten’s understanding of himself (though it is Akhenaten these scholars are explaining) and that is even antithetical to history.

An atheist is, naturally, compelled to understand history in an atheistic way but Breasted was apparently not an atheist; in his day, however – thanks to the anti-tradition of liberalism – scholarship was being saddled with the illusion that knowledge required avoidance of theological positions. You must write history as if the existence of God had no bearing on the facts. Breasted, as a ‘scholar’, did so and found himself thinking that any pharaoh who turns against the habits of

the most conservative nation in the ancient world,

Bob Brier, The History of Ancient Egypt, The Great

Courses: Ancient History (1999), lecture 21

already a thousand years old by Akhenaten’s day, must be the epitome of a man acting alone, against tradition. But this is to take the lead of liberalism and follow it into the deep confusion about ‘conservatives’ and ‘rebels’ that modern thinking has mired us in.

Breasted wrote,

Until Ikhnaton [Akhenaten] the history of the world had been but the irresistible drift of tradition. All men had been but drops of water in the great current. Ikhnaton was the first individual in history. Consciously and deliberately, by intellectual process he gained his position, and then placed himself squarely in the face of tradition and swept it aside. He appeals to no myths, to no ancient and widely accepted versions of the dominion of the gods, to no customs sanctified by centuries….

Breasted, Development of Religion & Thought, 339

Assuming the throne around 1353 BC, what Akhenaten needed to do, writes Breasted, was gather an army to maintain the empire his father Amenhotep III had extended to Syria and Nubia; instead he developed a new religion, pulling up (root and branch) the religious traditions of the Egyptian people. Within a very few years, thanks to Akhenaten,

their holy places had been desecrated, the shrines sacred with the memories of thousands of years had been closed up, the priests driven away, the offerings and temple incomes confiscated, and the old order blotted out. Everywhere whole communities, moved by instincts flowing from untold centuries of habit and custom, returned to their holy places to find them no more, and stood dumfounded before the closed doors of the ancient sanctuaries.

Breasted, Development of Religion & Thought, 340

Egypt had established a great civilization with a prosperity envied by every neighbouring state, but Akhenaten was not a conservative: he was an individual, a rebel who

accomplished this revolution by imposing his own ideas, ideas born in his own mind, upon the external world.

Leslie A. White (paraphrasing Breasted),

“Ikhnaton: The Great Man vs. The Culture Process,”

Journal of the American Oriental Society 68:2 (1948), 93

THE OMISSION OF TRUTH

This may be proper scholarship but the principle missing from this historical account is truth. There is not just a perpetuated tradition versus individuals hatching their own ideas, there is the truth about Egypt and divinity that was the motivation of Akhenaten’s indeed radical behaviour. If there are simply state gods, different for all peoples (for Egypt the gods Isis, Osiris, Horus, Re, et al.) – gods who are for Egypt exclusively and

who crushed all peoples and drove them tribute-laden before the Pharaoh’s chariot

– that dictates one way of worshipping and governing, but if there is one god who is the creator of everything encompassed by the sun, who is

the beneficent father of all men,

Breasted, A History of Egypt, 377

then this, truly, will demand a complete rethinking of worship. On this Breasted makes a fascinating comment, relative to particulars,

It is the first time in history that a discerning eye has caught this great universal truth. [Akhenaten’s] whole movement was but a return to nature, resulting from a spontaneous recognition of the goodness and the beauty evident in it, mingled also with a consciousness of the mystery in it all, which adds just the fitting element of mysticism in such a faith.

‘How manifold are all thy works! … O thou sole god, whose powers no other possesseth’.”

Breasted, A History of Egypt, 377,

citing the Hymn to Aten

The divine order was either one way or the other, and if it was the way Akhenaten perceived it to be then this fact of the matter must affect your assessment of the character of this drama, which is not so plainly a rebellion.

Does a conservative conserve what is untrue? If Egyptian culture had distinguished itself by

a constant emphasis upon ‘truth’ such as is not found before nor since. [If] the king always attaches to his name the phrase ‘living in truth’,”

Breasted, A History of Egypt, 377

was it rebellion to correct Egypt’s thralldom to powerless gods? As for inherited tradition Akhenaten was in no way against it (he was not disposing of the traditional understanding of marriage, government, sex and gender, society, the place of religion in society, all of which we are seeing today). But even in the sector of religion was Akhenaten ‘planting himself squarely in the face of tradition and sweeping it aside’ in changing the religion to favour the god, the one god, who had both given Akhenaten his role (in Egyptian thought it was the god “who placed him on his throne” – this phrase was part of the pharaoh’s very name | Breasted, Development, 357) and endowed Egypt with all her fruitfulness – or was Akhenaten holding to the highest principles of his tradition, which he was now compelled (by his understanding of the truth) to choose among? (What was greater, according to Egypt’s own way of thought: the divine power that Egypt’s tradition yoked the nation to, or the whole creaking parcel of its religious traditions?)

her fruitfulness – or was Akhenaten holding to the highest principles of his tradition, which he was now compelled (by his understanding of the truth) to choose among? (What was greater, according to Egypt’s own way of thought: the divine power that Egypt’s tradition yoked the nation to, or the whole creaking parcel of its religious traditions?)

If something in our grasp of the order of things (which Egypt had always counted crucial to its life) is seen to be false, why perpetuate it: why not correct the understanding and perpetuate that? As Jesus did, correcting the notions held by the Sadducees and Philistines about the law and the Jewish unbelief in the afterlife.

There is no question that Akhenaten had dealt a staggering blow to the religion of other Egyptians (which surely was a fatal miscalculation as to how he, as pharaoh, should guide Egypt in response to Aten, because it would wipe out Atenism), but a pharaoh who ignored his understanding of reality, the very terms on which his people would survive, was not “living in truth” and was no steward of his nation. If the nation’s grasp of reality was visibly false it was precisely the pharaoh’s responsibility to do something about this.

When I say visibly false I am alluding to that “visible evidence” mentioned by Breasted: the beauty of all of nature, in all the lands of the world, which was divinely created. Breasted writes that Akhenaten, turning to Aten,

appeals … to no customs sanctified by centuries – he appeals only to the present and visible evidences of his god’s dominion, evidences open to all,….

Breasted, Development of Religion & Thought, 339

Well, this is not individuality, not a man striking off on his own path, the path of an individual. We are not looking at ideas “born in” (hatched in, fabricated in) a man’s “own mind”.

THE HISTORIAN’S NEED TO RECOVER HIS EYES

Scholars may not be permitted to count God an entity but God is a mover of history. He acted on the Pharaoh in Exodus 12 and that was not the only occasion.

Akhenaten is not a man alone, turned against tradition. If there is a God reigning over all, who speaks through light, then in his actions (miscalculated as they were) Akhenaten was a man less alone than ever, because he was in community with his creator.

It might very well be said of Akhenaten what Augustine said of himself:

I entered into the depths of my being under Your guidance, and I was able to do it because You helped me. I entered and with the eye of my soul, such as it was …

– and here make some allowance for the condition of Akhenaten’s soul, or mind, “such as it was,” which did not entirely reach the insights that Augustine relates in the following words, but was nonetheless walking exactly this path.

I saw … the unchangeable light. It was not that common sunlight which is open to the eye of the flesh,…. This other light was different…. It was not above my mind … as the sky is over and above the earth. Rather it was above me because it made me, and I was beneath it because I was made by it. It is the man who knows truth who knows that light,….

Augustine, Confessions, 7.10; trans. George Howie

The world, in its own exact particularity, in the order of the sun (which marks time by its regular motion, gives us the heat that warms us and the light by which we see all beauty), speaks of God.

The heavens declare the glory of God.

Psalm 19:1

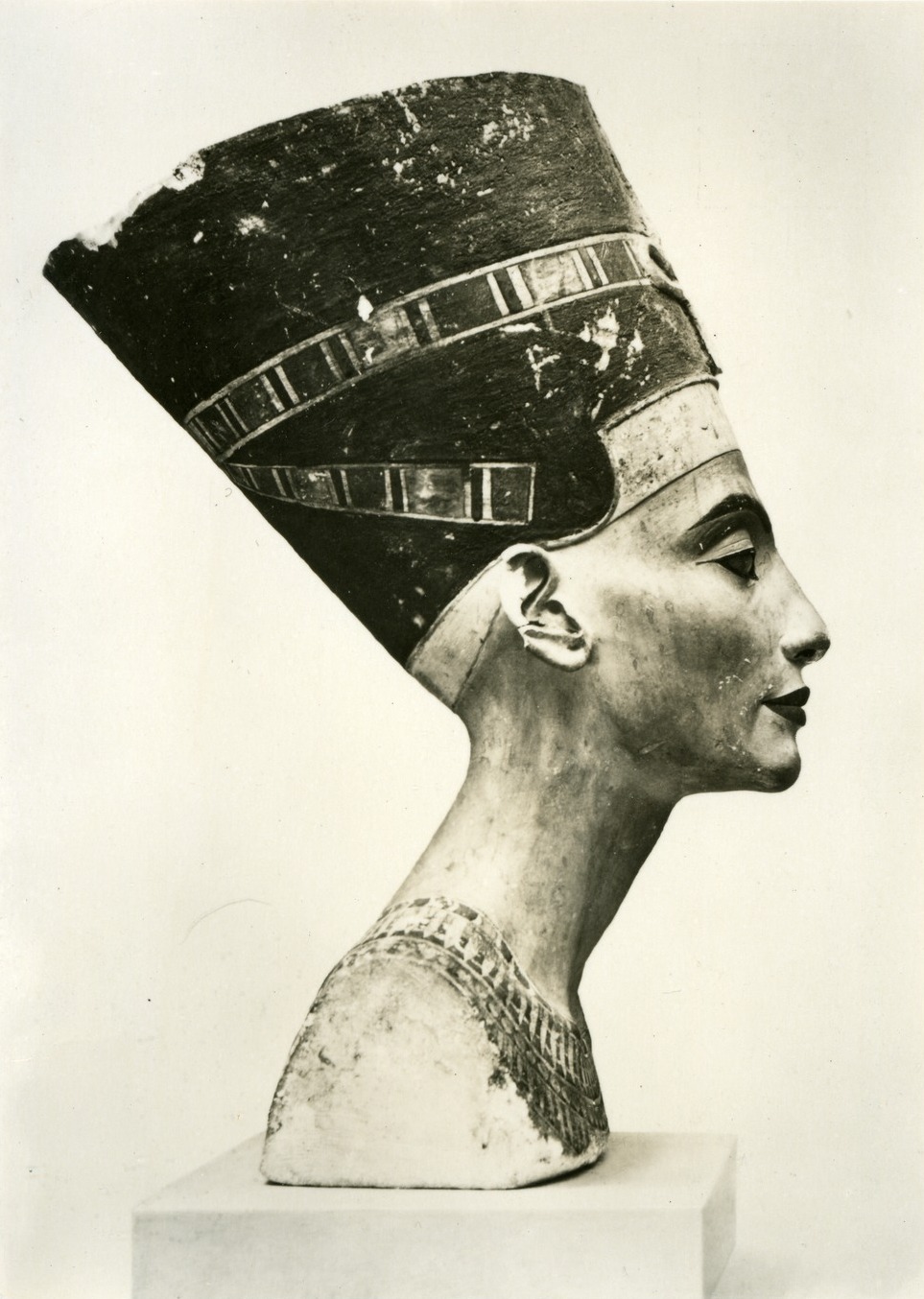

4 | The Berlin head

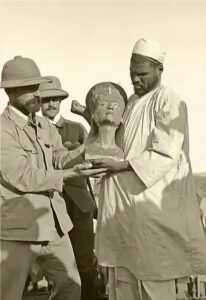

The bust of Nefertiti was found in 1912 in an excavation led by German archeologist Ludwig Borchardt. It was discovered in the rubble of the new capital, built by Akhenaten, that he called Akhetaton, ‘Horizon of Aten’, a city that, soon after Akhenaten’s death in the seventeenth year of his reign, was vacated and then obliterated – reduced to a desert wasteland called on the map Tell El-Amarna.

The bust of Nefertiti was found in 1912 in an excavation led by German archeologist Ludwig Borchardt. It was discovered in the rubble of the new capital, built by Akhenaten, that he called Akhetaton, ‘Horizon of Aten’, a city that, soon after Akhenaten’s death in the seventeenth year of his reign, was vacated and then obliterated – reduced to a desert wasteland called on the map Tell El-Amarna.

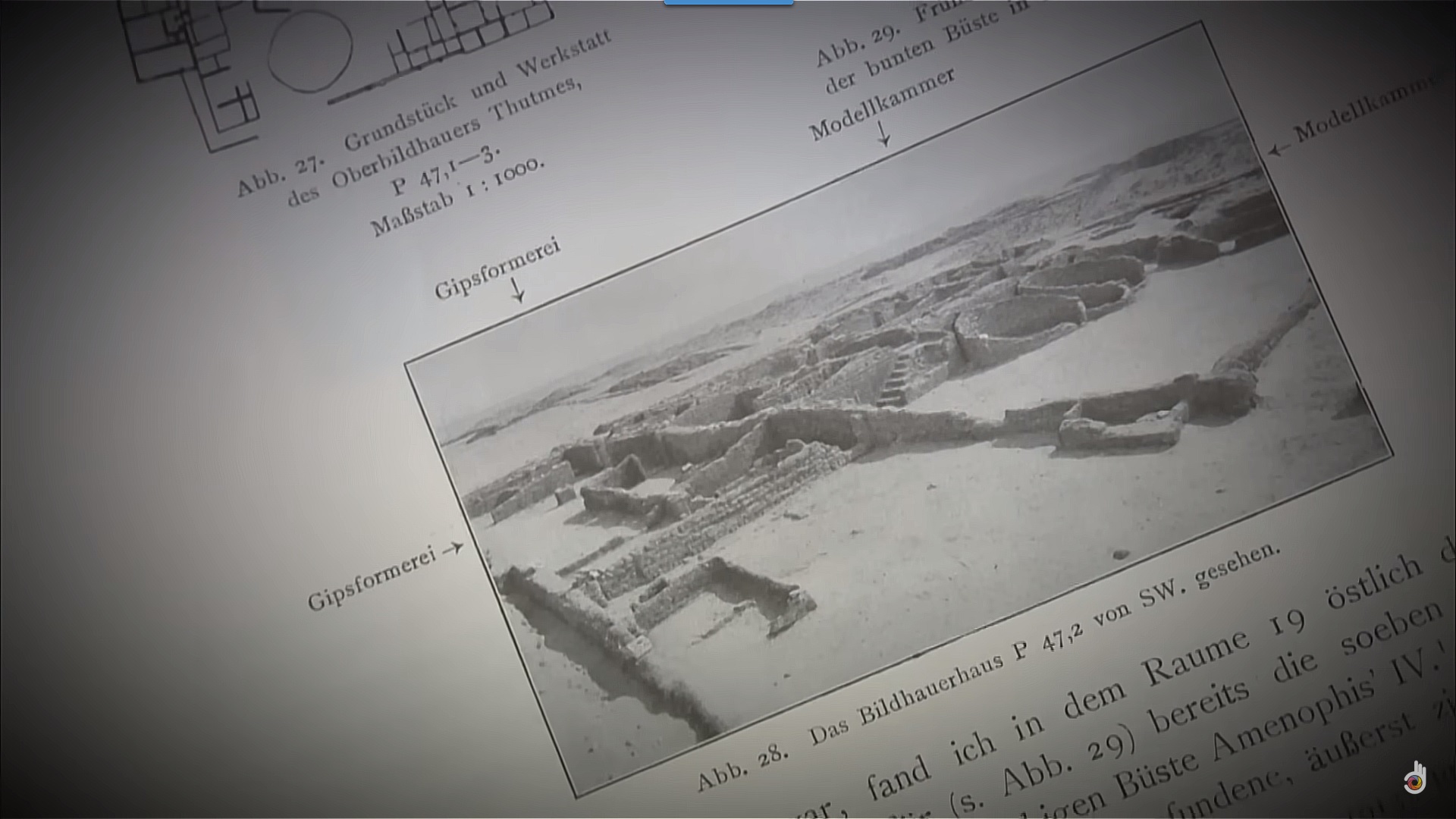

AMARNA

Akhetaton is a unique archeological site because it has no strata. It was home to a single generation of people, functioning as a city for only some twenty years before being razed to the ground in a purgation of Atenism. The plan of the city, visible from the traces of foundations, marks the layout of the city just as Akhenaten built it. When Borchardt announced his plan to dig at this site the famous British archeologist who had done so decades earlier scoffed, claiming there was nothing there to find – but in the rubble of a house in a section of the city home to the artisans who built it,  this statue was found under a metre of debris from the ruins of the house in a cache of carvings and sculpting tools.

this statue was found under a metre of debris from the ruins of the house in a cache of carvings and sculpting tools.

The tools and the unfinished sculptures all found within the perimeter of this building identified it as the compound of a master sculptor who has been identified from a fragment of ivory bearing the words,

The tools and the unfinished sculptures all found within the perimeter of this building identified it as the compound of a master sculptor who has been identified from a fragment of ivory bearing the words,

the praised one of

the Perfect God,

the chief of works,

the sculptor Thutmose.

Tyldesley,

Nefertiti’s Face, 27

Tyldesley writes,

Thutmose’s workshop specialized in royal statues … commissioned by the king and his representatives,…. Whereas other kings had commissioned sculptures of Egypt’s many gods plus the royal family, Akhenaten commissioned statues of himself and his family exclusively,

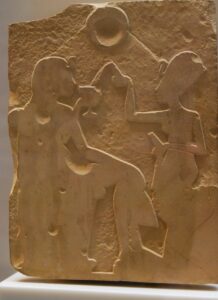

as it was the king and the queen who were directly linked to Aten – the god that from the fourth year of Akhenaten’s reign was represented as

a faceless, bodiless disc which hung in the sky emitting long, thin rays ending in tiny human hands

– extended expressly to the royal family.

Atenism was not a democratic religion [a religion for the demos or people], and the common people were not expected or even encouraged to worship the state god. This was the privilege of the elite,…. Prominent citizens who could not access the temple were expected to worship the Aten using the royal family as intermediaries. For this purpose, their homes were furnished with statues of the king and queen, or carved stone stelae depicting the royal family going about their daily business beneath the Aten’s rays.

Thus there were three other Nefertiti statues found alongside the Berlin bust. Tyldesley writes that

it is a testament to the productivity of the royal workshops that, in spite of the post-Amarna attacks, we have more engravings and sculptures of Nefertiti than of any other Egyptian queen, Cleopatra VII included.

Tyldesley, Nefertiti’s Face, ch. 1

Because the Berlin statue

has a smooth base that allows it to stand firm, we can be confident that it is a complete artefact and not simply a head that has snapped off a larger statue.

Tyldesley, Nefertiti’s Face, ch. 4

We can imagine it, or rather the statues of Nefertiti modelled after it, standing in a home or an official building.

It is significant that the Berlin Nefertiti has only a right eye, the left eye not being lost but apparently never added. The completed eye is filled with

It is significant that the Berlin Nefertiti has only a right eye, the left eye not being lost but apparently never added. The completed eye is filled with

black-coloured wax placed in the white-painted eye-socket and covered with a thin (2 mm) lens of rock-crystal engraved with the outline of the iris,

Tyldesley, Nefertiti’s Face, 116

but the left socket lacks any trace of such material. The statue is therefore finished (smoothed and fully painted) but not completed, which has suggested that it was created to serve as a prototype for use in this workshop that turned out statues of Nefertiti, multiples meant for more than one building in the city. Akhetaten was created to be a beautiful city.

‘SHE IS LOVELY & BEAUTIFUL’

We know of that plan from public declarations that Akhenaten had carved into some of the wall-like stones that mark the city boundary.

I have made Akhetaton for my father as a dwelling.

It belongs to my father, Aton,

who is given life forever and ever.

The city was made fitting for Aten as a dwelling and an offering by being made beautiful.

The whole land shall come hither, for the beautiful seat of Akhetaton shall be another capital.

Words carved into one of the wealthier houses characterize the city:

Akhetaton, great in loveliness, mistress of pleasant ceremonies,…. At the sight of her beauty there is rejoicing. She is lovely and beautiful; when one sees her it is like a glimpse of heaven….

Stelae inscriptions in Breasted, Development of

Religion & Thought, 365–66

We might mistakenly imagine that we have just read a description of Nefertiti, not a city, but that is no accident. Beauty, the beauty of everything that is beautiful, is a trace of God in this ‘city of God’.

- To make a beautiful thing is to echo God – is to choose in your work, your city, what is ‘of God’.

- To offer such a thing to God is to give God back to Himself, and is at the same time to make a seat for God among you.

A thing “made … for my father as a dwelling” brings the Father’s presence, radiating his presence, here among us, in the homes where we are living.

ART & POWER

Because of that, in its beauty the city of Akhetaten was a centre devoted to power – but the ultimate power that manifests its might in beautiful form. Power over the soul, power to inspire, to prompt thankfulness. Power is not primarily power over the body but power over the will, which may indeed be obtained by exacting pain, but if a tortured person merely suffers (picks up his cross without submitting) his torture has failed.

Today people circulate pictures of Gothic and Baroque architecture tagged with the question, Why don’t we build this way anymore? But asking for beautiful buildings amounts to only half a request. Nostalgia for beauty does not identify the source that such things of beauty come from. Philosophers of art tell us that

we may doubt whether the ancient Egyptians achieved … consciousness of the aesthetic as such,

Monroe C. Beardsley, Aesthetics from Classical Greece

to the Present (University of Alabama Press, 1966), 22

but ‘achieving’ this ‘aesthetic consciousness’ would constitute a lapse for Egypt: would effectively remove it from the communion that generated the beauties of Egypt’s civilization.

Beauty understood aesthetically – in terms of aesthesis, the Greek word for sensation and perception – has buried itself in the receptor, in man, and in this retrenchment just ceases to be understood. So long as all we are thinking about is the experience of beauty (which we want again) it will elude us, because it flowed from life with God. It is only a culture that knows what beauty is – that says, in the way of a culture,

My eyes behold thy beauty every day, O my lord,

Thou fillest every land with thy beauty

O thou sole god, whose powers no other possesseth

Hymn to Aten; in Breasted, A History of Egypt, 369, 371, 374

– only such culture opens itself to the power that sustains life, a pre-eminent concern of culture.

Akhenaten wished to align Egypt with the true source of power and dedicated his city to beauty, building and dressing his city with sculpture and painting. Along such lines those ‘in power’ today produce nothing. The head of a country today has no vision of beauty at all and is entirely devoid of the power Akhenaten wielded in his submission to the divine. In that, Akhenaten made no error; his mistake was to believe that the creator of all desires communion only with the king, is known by him alone:

There is no other one who knows you.”

Hymn to Aten; in Darnell & Darnell, 292

His error lay in the misunderstanding of his god.

4 | Individual beauty

THE VERY IMAGE OF NEFERTITI

The purpose of the Berlin bust was to ensure that the statues made of Nefertiti were all images of her. But why did it matter

that the royal image remained constant wherever it might appear[?]

Tyldesley, Nefertiti’s Face, ch. 1

In carvings on the walls of tombs Nefertiti could be identified by the flat-topped blue crown that was unique to her (no other queen wears such a crown). But if lines cut into stone were images of Nefertiti in one sense

they lacked all capacity to convey the character of her individual face. It is not her face that we are seeing there but a depiction that tells us of her (in the image above, that she makes offerings to Aten, for instance), and Akhenaten evidently desired something beyond this. Not simply representations of Nefertiti (which people could correctly identify) and of acts that she performed but Aten’s own work.

they lacked all capacity to convey the character of her individual face. It is not her face that we are seeing there but a depiction that tells us of her (in the image above, that she makes offerings to Aten, for instance), and Akhenaten evidently desired something beyond this. Not simply representations of Nefertiti (which people could correctly identify) and of acts that she performed but Aten’s own work.

You create their faces,

Hymn to Aten; in Darnell & Darnell, 292

says Akhenaten in the hymn. Akhenaten desired the presentation of her actual image. It was her image and appearance that radiated her beauty.

The bust created by Thutmosis was thus a carving that, first, ‘transmitted the original’ – by which I mean the particular appearance of Nefertiti – to the stone, and then, operating as a reference template, allowed other sculptors to replicate her image and bring Nefertiti’s beauty, … divine beauty, … to others in the new city.

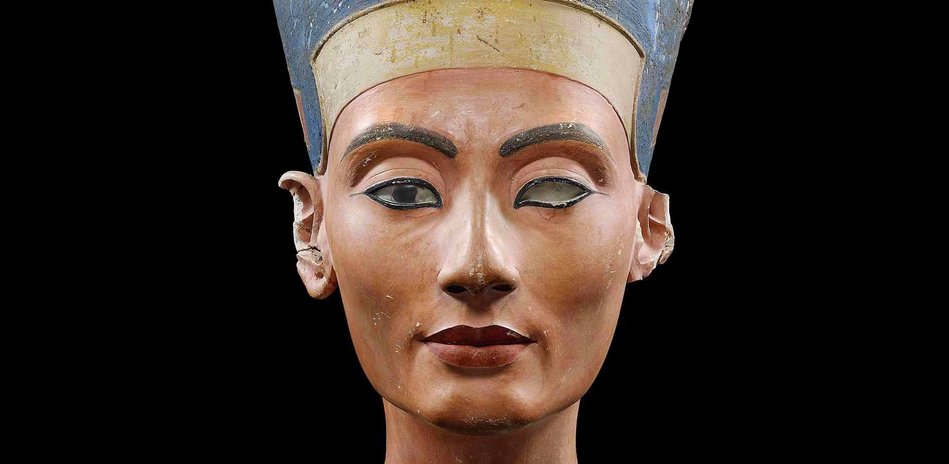

Borchardt, in 1923, wrote that the face we are shown is

the epitome of tranquility and harmony.

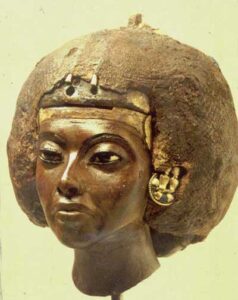

(We see this instantly when we compare it with a head of Queen Tiye, Akhenaten’s mother: while Tiye’s face is filled with a disturbing tension, Nefertiti’s is a heavenly oasis.)

(We see this instantly when we compare it with a head of Queen Tiye, Akhenaten’s mother: while Tiye’s face is filled with a disturbing tension, Nefertiti’s is a heavenly oasis.)

Viewed straight on, it is perfectly symmetrical, but nevertheless, the viewer is never in doubt that he has before him not just any imaginary ideal image but rather the likeness, at once stylized but simultaneously true, of a specific person with a highly distinctive appearance.

Ludwig Borchardt, Porträts der Königin Nofretete aus den Grabungen 1912/13 in Tell el-Amarna

Ludwig Borchardt, Porträts der Königin Nofretete aus den Grabungen 1912/13 in Tell el-Amarna

(Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung, 1923), 33;

cited by Tyldesley

Writing in those years Borchardt was entirely unaffected by the late-20th-century belief (still dogma today) in the absurdity of the idea of a “true” image. (There is no truth to capture. Every attempt to render simply imposes its own preferences, its own idealizations. Any intention to ‘copy’ a form abandons the very purpose of art.) Borchardt appreciates that in a medium such as we have here (carved limestone coated with layers of gypsum plaster only a few millimetres thick) there must be some reduction of Nefertiti’s form (some degree of stylization) and the symmetry given might well surpass that of the original, but none of this prevents the distinctive appearance of an actual person from coming into the gypsum and stone. The original, with its power, can be manifest in the work.

WHAT IS INDIVIDUAL BEAUTY?

What is individual beauty? I have already remarked on the mystery that there is such a thing, but what it is we might finally reflect on.

In the Berlin Nefertiti we are not given a generalized face (with the basic components in their right places). It is strangely difficult to identify what makes individual beauty distinct from the generalized beauty that we see in the faces of, say, the Knidian Aphrodite or the Venus de Milo (also beautiful); what we can say with confidence, however, is just what Borchardt does: looking at the Nefertiti

In the Berlin Nefertiti we are not given a generalized face (with the basic components in their right places). It is strangely difficult to identify what makes individual beauty distinct from the generalized beauty that we see in the faces of, say, the Knidian Aphrodite or the Venus de Milo (also beautiful); what we can say with confidence, however, is just what Borchardt does: looking at the Nefertiti

the viewer is never in doubt that he has before him … the likeness … of a specific person with a highly distinctive appearance.

It is a commonplace to say that what is beautiful about the face of Nefertiti is its symmetry, but that is shared with generalized faces. What is distinctive and beautiful about this face is the particular whole, the plethora of decisions made by the artist who has created this face (Akhenaten is right: it is God), these being decisions ignored – even avoided – by the artist designing generalized faces.

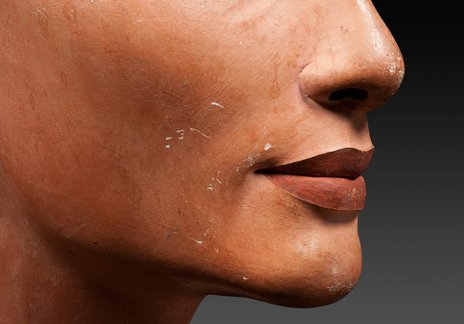

Such as the exact shape of the eyes, which are her eyes. We are not looking at ‘almond shaped’ eyes and ‘well defined’ brows; these generics only hint at what is before us, which is all that words can do. The shape of the eyes is far more complex, and it gives the eyes their own languid expression. Likewise the shape of the lips, which are the lips of a particular woman. (Though they might have appeared in Nefertiti’s children what everyone would then have said was, ‘Look, Meritaten has her mother’s mouth’.) Ears are usually not represented with this sculptural fullness and detail, all of their elements captured just as they are: another complex and beautiful feature. High cheekbones are often treated as a kind of guarantor of female beauty but are not always beautiful; what matters is the entire harmony, the character of the transition from the cheekbones to the region of the mouth, which in Nefertiti is utterly distinct.

Such as the exact shape of the eyes, which are her eyes. We are not looking at ‘almond shaped’ eyes and ‘well defined’ brows; these generics only hint at what is before us, which is all that words can do. The shape of the eyes is far more complex, and it gives the eyes their own languid expression. Likewise the shape of the lips, which are the lips of a particular woman. (Though they might have appeared in Nefertiti’s children what everyone would then have said was, ‘Look, Meritaten has her mother’s mouth’.) Ears are usually not represented with this sculptural fullness and detail, all of their elements captured just as they are: another complex and beautiful feature. High cheekbones are often treated as a kind of guarantor of female beauty but are not always beautiful; what matters is the entire harmony, the character of the transition from the cheekbones to the region of the mouth, which in Nefertiti is utterly distinct.

One could fall in love with the gently convex forms that frame her mouth and their correlation with the concavity along her upper lip, all coming together, in their specific detail, into a reserved smile. And one could love equally the extraordinary elongation of her neck and the surprise of its incline, far extended but utterly relaxed and stable.

The whole set of her head on her shoulders is a kind of remarkable gesture. – And so on, including the lines on her eyelids and the ‘imperfect’ swelling beneath her eyes.

The whole set of her head on her shoulders is a kind of remarkable gesture. – And so on, including the lines on her eyelids and the ‘imperfect’ swelling beneath her eyes.

Nefertiti in this image has been called “aloof” and “remote” (Joyce Tyldesley, Nefertiti: Egypt’s Sun Queen [London: Penguin, 2005], 4) but another writer has drawn attention to her gaze, which is

directed energetically toward the front, fixed so directly on an invisible person opposite that it seems impossible to escape.

D. Wildung, The Many Faces of Nefertiti

(Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2012), 22

That is not detachment but relation; further, to be looked at so intently by so welcoming and not-aloof-but-serene a face is not a condition from which you would wish to escape.

Breasted writes,

Breasted writes,

It is evident that the artists of Ikhnaton’s court were taught by him to make the chisel and the brush tell the story of what they actually saw.

Breasted, s.v. “Ikhnaton,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 14th ed., 79

They saw particulars, which are filled with eternal beauty. In the Berlin Nefertiti we do not see only a general ideal,

the ideal feminine beauty [that is] depicted in Egyptian love poetry, which was emerging around [Akhenaten’s] time.

‘The handsomest of all!

She looks like the rising morning star….

Shining bright, fair of skin,

Lovely the look of her eyes, ….

Upright neck, …

Captures my heart by her movements.

She causes all men’s necks

To turn about to see her.’

Dimitri Laboury, “‘The Beautiful One Has Come’:

The Creation of Nefertiti’s Perfect Portrait,”

in Tutankhamun: Discovering The Forgotten

Pharaoh, ed. Simon Connor & Dimitri Laboury

(Presses Universitaires de Liège, 2020), 164;

poem translation after Miriam Lichtheim

We see much more: the entirely individual beauty of a single person – and, if we have eyes, the path it opens to the eternal divine.

[]

From ancient times it was known that beauty was divine and possessed by all the creations of God, but in their kinds as well as in their particularity. And in the West this was eventually forgotten, owing to a growing nihilism that infected even Christians – nihilism as Nietzsche explained it.

What does nihilism mean? … The aim is lacking; ‘why?’ finds no answer.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power:

Attempt At a Revaluation of All Values

(Studies & Fragments), book 1, sec. 2

(spring–fall 1887)

But the answer has never been lacking. It was always voiced, in the language of beautiful and individuated exemplars of their kinds, speaking each in their own way of the answer. Ceasing to believe in this voice, seeing the world as a mass of dumb particulars, is the erasure of ancient belief via a shift to nihilism itself.

.

Artist Thutmose

Date c. 1335 BC

Collection Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung

Titled there Bust of Nefertiti

Medium Limestone, painted stucco, quartz, wax

Dimensions 48 cm tall | 19 in

Weight 20 kg | 44 lb

Photo source Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Sandra Steiß