Ideal government VI | Lorenzetti’s political ‘Philosophia’

In this essay,

• THE WELL-GOVERNED LAND & ITS SPIRIT

• THE ‘PROJECT’ OF POLITICS

• THE ONE SUCCESSFUL POLITICS

• IMAGE OF THE IDEAL – THE HEAVENLY JERUSALEM

• PHILOSOPHIA, THE SUCCESSFUL PURSUIT

Best viewed on larger screens

The last of six parts:

I Government II Tyranny III Justice IV Common good V Politics

1 | The well-governed land & its spirit

We at last turn to the final wall of imagery in the Sala dei Nove or Room of the Nine governors of Siena, the long east wall entirely devoted to a depiction of Siena and its surrounding countryside: Lorenzetti’s picture of life as it should be (at least in so far as the land is governed well).

Art historian Joseph Polzer writes that if this wall were gone and the city beyond it (Siena as of 1340) were made visible by its removal, something like what Lorenzetti painted would be seen.

Art historian Joseph Polzer writes that if this wall were gone and the city beyond it (Siena as of 1340) were made visible by its removal, something like what Lorenzetti painted would be seen.

Insofar as possible, the panorama on the eastern wall was so disposed that it would correspond as best as possible to the actual layout of Siena if the wall supporting the mural were dissolved. Accordingly, the bell tower and dome of the cathedral in the upper left corner … would conform roughly to their actual location. And the city wall to the right of the town, including the sharp descent into the valley and the rolling hills rising beyond, would correspond roughly to the view of the contado beyond the southern windows. In short, the mural on the eastern wall represented Siena viewed from the location of the Nine in the Palazzo Pubblico.”

Joseph Polzer, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s ‘War and Peace’ Murals Revisited:

Contributions to the Meaning of the ‘Good Government

Allegory’,”Artibus et Historiae 23:45 (2002), 70

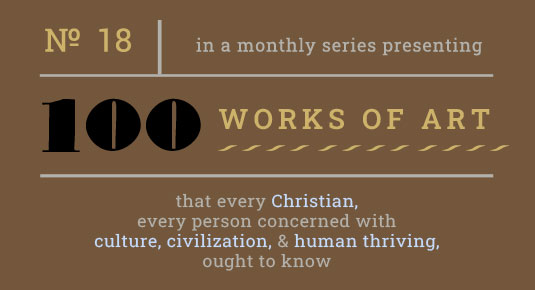

Presiding over this long panorama, just where the city wall meets the countryside, is one symbolic entity.

The realism of the city and the adjoining landscape does not wholly exclude the presence of allegory … in the personification of the winged Securitas located beside Siena’s city gate.”

Polzer, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s ‘War and Peace’ Murals Revisited,” 70

In the centre, above city and country, hovers Securitas in the form of a winged genius [or spirit].”

Uta Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace:

A New Interpretation,” Journal of the Warburg

and Courtauld Institutes 35 (1972), 148

In her right hand this figure displays a partly unrolled scroll, on which we read,

Without fear every man may travel freely

and each may till and sow,

so long as this commune

shall maintain this lady sovereign,

for she has stripped the wicked of all power.”

Translated by Ruggiero Stefanini in Randolph Starn & Loren Partridge,

Arts of Power: Three Halls of State in Italy, 1300–1600

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 266

To whom do the words “this lady” refer? Perhaps, indeed, she is

duly identified by name,”

Polzer, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s ‘War and Peace’ Murals Revisited,” 70

by the word “SECURITAS” written above her. Partridge and Starn, however, say that there is room for doubt: their translator, they note,

prefers Justice, although ‘this lady’ may also be Security.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 266

There is, however, a very good reason to believe that Securitas is not her name, but identifies, rather, what she brings (security from harm, or peace) or what she does (she secures all the goods essential for life, peace among them) – in a strict echo of the analogous figure on the wall opposite her. That figure is the bringer of timor (terror and fear, the evil result of a failure in governance), and about the great calamity depicted on that wall we could indeed ask: into whose hands does a tyrant governor place his people. The answer to that question is surely Death,  signalled by the corpse-like appearance of the figure bringing timor. The tyrant allows his people to fall into the hands of Death, who roams through the land unopposed, swinging the sword as it will. We see in the image on the west wall how the land becomes a haunt of death and destruction, and the death reigning over Siena is manifest not simply in the corpses that Lorenzetti has painted but also in the souls of men. Souls are invisible but the acts of the killers, rapists, and terrorizing brigands that roam the landscape are as plain as day, and telegraph the condition of the souls directing those acts. It is the appearance of these figure that tells us who these figures are.

signalled by the corpse-like appearance of the figure bringing timor. The tyrant allows his people to fall into the hands of Death, who roams through the land unopposed, swinging the sword as it will. We see in the image on the west wall how the land becomes a haunt of death and destruction, and the death reigning over Siena is manifest not simply in the corpses that Lorenzetti has painted but also in the souls of men. Souls are invisible but the acts of the killers, rapists, and terrorizing brigands that roam the landscape are as plain as day, and telegraph the condition of the souls directing those acts. It is the appearance of these figure that tells us who these figures are.

On the east wall there is something unusual about the appearance of the figure hovering there: a striking and complete disjuncture between the security named by the label and the appearance of the figure identified (these scholars claim) as the state of security. But why would ‘Security’ be virtually naked, clothed only in a filmy strip of fabric? Why

On the east wall there is something unusual about the appearance of the figure hovering there: a striking and complete disjuncture between the security named by the label and the appearance of the figure identified (these scholars claim) as the state of security. But why would ‘Security’ be virtually naked, clothed only in a filmy strip of fabric? Why

assum[e] the shape of a winged woman whose antiquising nude body is partly covered by a wind-blown veil”?

Polzer, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s ‘War and Peace’ Murals Revisited,” 70

It is especially unlikely that this figure is Security when exactly this manner of depiction (a nude figure veiled in such a way as to thematize revealing, as we discussed earlier) is a traditional way of representing another figure that is in fact central to the imagery in the Room of the Nine. That figure is Wisdom.

WISDOM

In Augustine’s Soliloquies (written a millennium earlier outside Milan, not so very far from Siena), Augustine personified wisdom as a precious but unattained beloved:

In Augustine’s Soliloquies (written a millennium earlier outside Milan, not so very far from Siena), Augustine personified wisdom as a precious but unattained beloved:

But if, as I desire, I ever attain Wisdom, I will do what she advises.”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Michael Foley,

St. Augustine’s Cassiciacum Dialogues, vol. 4

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020),

book 1, ch. 4; 28

In that work Wisdom is understood as God, drawing Augustine to Him. Augustine begins the book with a prayer:

This alone do I beg of Thine Most Excellent Clemency – that Thou convert me completely to Thee, that Thou let nothing impede me in my striving toward Thee, and that Thou command me … to be … a perfect lover and recipient of Thy wisdom, someone who is both worthy of Thy dwelling place and a dweller in Thy most blessed kingdom. Amen.”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Foley, book 1, ch. 1; 24

As art historian George Rowley noted of the figure of Wisdom portrayed on the north wall,

As art historian George Rowley noted of the figure of Wisdom portrayed on the north wall,

the origin of wisdom is not human reason but divine reason, in which Justice and Concord have their source.”

George Rowley, Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Princeton, N.J.:

Princeton University Press, 1958), 100

But, as Augustine remarks in the words cited above, wisdom is the glory of God given to men by God. If Wisdom can be spoken of abstractly as “the supreme good”, this formulation cannot do justice to the character of such a good, and Augustine therefore prefers to personify Wisdom. In his text he therefore shifts from speaking as a philosopher to speaking as a lover – though of course, as Augustine knew even better than we do, that alternation is itself simply philosophy: philo-sophia, love of wisdom. (The more philosophy is clear and technical, the more it loses touch with the wondrous sun that calls it forth, drawing us out of the cave.)

Augustine writes of the human mind, a mind made capable, by divine design, of seeing the good, while at the same time incapable of seeing, given the magnitude of her glory – a duality that delivers the classical image (touched on in the last segment) of the veil that conceals as it reveals, reveals as it conceals.

I am forced for the moment to agree with Cornelius Celsus, who said that the supreme good is wisdom and the supreme evil is bodily pain. Nor does his reasoning strike me as absurd.

‘For since,’ he says, ‘we are composed of two parts – the soul, of course, and the body – and since … the supreme good is the best of the better part while the supreme evil is the worst of the inferior part. Wisdom, moreover, is the best in the soul, and pain is the worst in the body.’

And so it is concluded (without any falsity, in my opinion) that the supreme good of man is to be wise and the supreme evil is to be in pain.”

(In the Soliloquies, which are written as a dialogue that Augustine conducts with himself, that comment is answered by Reason or Augustine’s own rational mind.)

Reason: We’ll see about those things later. For perhaps Wisdom herself, which we are striving to attain, will persuade us.”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Foley, book 1, ch. 12; 42

But I have mentioned this text as an illustration of a tradition of imagery. What is said in the Soliloquies about “Wisdom herself” employs imagery that we have seen already on the central wall of this room.

But that supernal Beauty knows when she should show herself.”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. C.C. Starbuck, Nicene &

Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, vol. 7, ed. Philip Schaff

(Buffalo, N.Y.: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1888), ch. 25

The imagery here is that of the Song of Songs, of the beloved’s beautiful body given in love, and from the Book of Wisdom:

Wisdom … I loved her, … I desired to make her my spouse, and I was a lover of her beauty.”

Wisdom 8:1–2, in The Apocrypha, KJV

(Iowa Falls: World Bible Publishers, n.d.)

Now, … we’re seeking what kind of a lover of Wisdom you are. For she whom you long to see and hold in a most chaste gaze and embrace, with no covering in between and naked, so to speak, does not allow this [to happen] with any kind of man except the fewest and most favored of her lovers,”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Foley, book 1, ch. 13; 43

– and here, notably, we return to that issue that I emphasized when discussing the depiction of virtue per se on the north wall: you cannot lay hold of virtue. Virtue is given to you, providing you are true to her – providing it is she you love exclusively (and, as carefully noted in the text of Soliloquies, this is a thing that you can not only be fooled about but a thing that you must be fooled about, while you are yet “being healed”. (Wisdom is a healer; she

fulfills the function of a physician and understands who the healthy are better than the very ones who are being healed.”)

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Foley, book 1, ch. 25; 46

We, as far as we have emerged, seem to ourselves to see; but how far we were plunged in darkness, or how far we had made progress, we are not permitted either to think or feel,….”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Starbuck, ch. 25

But to return to what we were exploring – which was deficient love, untrue love, duplicity, inadvertent double-mindedness, enslavement by the lesser – the veil is not removed for just “any kind of man”. Only “the fewest and most favored of her lovers” … – dare I say it – deserve this.

For if you burned hot with love for some beautiful woman, wouldn’t she be right not to give herself to you if she discovered that you loved someone besides her? Will Wisdom’s most chaste Beauty show herself to you if you’re not on fire for her alone?”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Foley, book 1, ch. 13; 43

This ‘queen’ is a jealous queen who cannot be had; she must be won, by fidelity. Indeed, by a quality of fidelity that can also not be had. The lover must somehow be taught what it means to be faithful – to be “on fire for her alone” – and this will be a process of detachment from “other things”. Quite simply, it is only when the beloved, “the supreme good”, has come to colour all things, so that those things are either reflections of her (and are thus desirable), or are inversions of her (and are thus detestable), or are matters of indifference – so that, in this way,

This ‘queen’ is a jealous queen who cannot be had; she must be won, by fidelity. Indeed, by a quality of fidelity that can also not be had. The lover must somehow be taught what it means to be faithful – to be “on fire for her alone” – and this will be a process of detachment from “other things”. Quite simply, it is only when the beloved, “the supreme good”, has come to colour all things, so that those things are either reflections of her (and are thus desirable), or are inversions of her (and are thus detestable), or are matters of indifference – so that, in this way,

only for her sake did we seek or want other things”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Foley, book 1, ch. 25; 46

– only in that state does it become fully possible to live a true life, to act in such a way as to drive death away. To the extent that you are not dedicated to “her alone” tyranny remains, injustice is done, and life is lived in fear of other men.

The figure, then, who floats above the panorama of Siena in its safe and fulfilled state is Wisdom. And what is the general political message of this correlation between a “supernal Beauty”, who is supreme yet also veiled, and the scene spread out beneath her?

2 | The ‘project’ of politics

There is a question that emerges from this – from what we have just examined taken on its own, and from the imagery on the other walls with which it is integrated – about the project of politics within Christianity, or I might say Christianity understood as inheriting the kingdom that has been prepared for mankind (Matthew 25). Call this the project of Christian politics; what does this project amount to?

It can begin at any point, inspired by anything we have seen on these walls: by the wrongness of the horrors, by a hatred for tyranny, by the legacy of the Republic (which may be the significance of the she-wolf and infants linking the Commune with Rome), by insight into the centrality of virtue, or of justice, or by the common resolve (the Concordia) of a band of citizens to make Siena great again (what Italians later called risanamento, ‘making healthy again’) .

It can begin at any point, inspired by anything we have seen on these walls: by the wrongness of the horrors, by a hatred for tyranny, by the legacy of the Republic (which may be the significance of the she-wolf and infants linking the Commune with Rome), by insight into the centrality of virtue, or of justice, or by the common resolve (the Concordia) of a band of citizens to make Siena great again (what Italians later called risanamento, ‘making healthy again’) .

As we see on the east wall, Wisdom is the spirit presiding over Siena’s renewal or salvation from evil, to the extent that this is possible in an earthly city. In what state does the image on this wall place Siena: in a state of perfection? Is this heaven on earth – or is this simply the city in its well-governed condition? If it were the former, how would the body of  a criminal be hanging from a gallows? We must, then, be seeing the ideal of governance in the real world, where crime occurs. The hovering figure of Wisdom (guarantor of security) shows in her left hand how, as per the last line on her scroll, Siena under Wisdom will “strip the wicked of all power”. Giving Wisdom pre-eminence, the people will not tolerate the acts of the wicked.

a criminal be hanging from a gallows? We must, then, be seeing the ideal of governance in the real world, where crime occurs. The hovering figure of Wisdom (guarantor of security) shows in her left hand how, as per the last line on her scroll, Siena under Wisdom will “strip the wicked of all power”. Giving Wisdom pre-eminence, the people will not tolerate the acts of the wicked.

What exactly does that pre-eminence amount to?

The scroll Wisdom holds makes reference to “this commune … maintain[ing] this lady sovereign” – though another scholar translates the line as, “while this lady rules the land.”

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace,” 148

But ruling is a human task; Wisdom does not rule the land nor even when she is ‘kept sovereign’ does she reign over the rulers. She is rather the pursued, the fire lit in the ruler’s hearts by what she has revealed to them of the good. She is the fire that continually consumes their inadequate conceptions of her and of her qualities, of the ideals like justice that she gives to men.

Thus it is the Commune that rules the people and must do the maintaining noted on the scroll, which is to keep the Wisdom of God before them, in her transcendence (“Manterra Questa Don[n]a I[n] Signoria”). Terms that mean transcendence are often confused, in modern times, with sovereignty, which shifts the meaning from perfection and glory to authority and power. The relation to be maintained is that of the lover, not of the subject (carrying out fixed orders).

The pre-eminence of Wisdom over Siena is the place of Wisdom in the life of the citizen that we explored above, via Augustine: that is, her reality as “that supernal Beauty” who heals their vision and purifies their desires, through what Wisdom shows them. She is transcendent for those who can say, with Augustine, that

only for her sake did we seek or want other things.”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Foley, book 1, ch. 25; 46

The project of politics, then, is that very relationship, which is given visible expression in this panorama of a city and country in which Christians dwell. It is not, then, the welfare of the city, though as I have said it can begin in that way. The goal or focus of the project of politics is not the common good, or freedom from tyranny, as the pursuit of such a goal does not accomplish such results. All that bears this fruit is the pursuit of Wisdom, the ‘project’ of the love of the Ideal. Quotation marks are unavoidable for what is primarily a form of response.

The ‘project’ of politics can begin in any way at all and be conceived entirely in terms of political or societal ends, but it is never Christianized until the participant in politics has in some way come under the power of Wisdom, seeing and responding to the thing that rescues politics from its casual and ordinary descent into everyday tyranny.

Suppose, for instance, that a man, a governor of Siena, has a hatred for tyranny (which is a perfect doorway to true Christian politics). A hatred for tyranny is also a powerful impetus to tyranny. My good (EL BEN PROPIO) and the good according to my understanding are not the same thing; my sense of ‘the good’ is surely superior in that it entertains ‘genuine’ care for others, but both conceptions are tethered to the same attachment, one so commonly fatal to people chained to it: self-involvement. My understanding of the good is sure to favour my understanding of what life is for, marked by who I am.

Suppose, for instance, that a man, a governor of Siena, has a hatred for tyranny (which is a perfect doorway to true Christian politics). A hatred for tyranny is also a powerful impetus to tyranny. My good (EL BEN PROPIO) and the good according to my understanding are not the same thing; my sense of ‘the good’ is surely superior in that it entertains ‘genuine’ care for others, but both conceptions are tethered to the same attachment, one so commonly fatal to people chained to it: self-involvement. My understanding of the good is sure to favour my understanding of what life is for, marked by who I am.

For example, a coward. If I hate tyranny but at the same time lack fortitude, then my sense of the good will not provide genuine care. Without courage I, a governor, will not oppose the powerful members of my society, the Sienese ‘magnates’ who are active agents of tyranny within my city. So Siena will have me, as one of the Nine, urging upon the others (with clever rhetoric) a cowardly ‘hatred of tyranny’ that keeps me safe. So it turns out, after all, that I too am an advocate of My good (EL BEN PROPIO). Siena then has active tyranny, in the oligarchs who exploit their peasants unchecked by the Commune in which I rule. In that the Commune fears to bring its tyrants to justice, withholds justice from the people, and is governed by people like me (people who, deep within, are faithful to tyranny’s creed), Siena has tyranny. A fully republican tyranny is entirely possible; what is not possible is a virtuous tyranny, tyranny among those who act “only for her sake,” for the sake of Wisdom.

A virtually identical story can be told relative to all the other virtues represented on the north wall: the lack of any virtue depicted is the expression of a love that is in conflict with that person’s expressed concern for the good, however sincere. That person is tyrant material with lovely principles, a tyrant blind to his endorsement of tyranny – and in this way, actually, a worse tyrant than an open one (a manifest tyrant, we would not support).

That political project, the hatred of tyranny just described, did not become Christian politics for the reason that it was never captured by Wisdom: its ‘hatred of tyranny’ was never subjected to the light of Wisdom, because the agent of that supposedly Christian politics did not himself live in the relation of the lover – the one relation, says the scroll carried by Wisdom, that was to be maintained, so that Securitas (the securing of the benefits depicted in this image of Siena) could be realized. Rulers ruling on any other basis than love of Wisdom could not deliver it.

When the theorists who underwrote the political vision set out in the Room of the Nine (Aquinas or Brunetto Latini or Augustine) say that “the supreme good of man is to be wise” what is meant is, to be in love with Wisdom: to be overwhelmed by her beauty, by the essence of goodness – to be entirely resensitized by her.

POLITICS OF THE KINGDOM

The project of politics, therefore, is … entry into the kingdom that God has prepared for us. To inhabit that kingdom is to live with God, seeing God – that is, in His glory, not as a sovereign (a projection of human rule, a ‘hater of tyranny like us’). It is in this relationship that the one who might have begun the project with an expressly political end (suppose that his objective was the restoration of justice, for instance) comes to discard deficient (self-protecting) and defective (e.g., cruel) conceptions of justice, permitting him to realize the city we see portrayed here. In this light it is perfectly sensible that when Jesus answers a question about the Kingdom of God he very soon shifts into,

for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me,” etc.,

Matthew 25 ESV

since it is through those who dwell in the Kingdom (in sight of Wisdom) that these eminently political goods are most securely (Securitas?) to be realized.

Threats to the order of society (to the common good and the happiness of all) will not thereby be eliminated (man remaining sinful), but such threats will gradually cease to come from the Commune itself if the citizens who form it truly enter, however this is made possible, into the pursuit of Wisdom on the path toward God.

Describing the north wall, historian of medieval Italy Daniel Waley writes that,

The horrors of bad government include robbery on the highway by an armed band, and a man lies murdered just outside the city gate: the entire countryside is dominated by the figure of Fear. In the contrasting scene of good government the corresponding figure of Safety (Securitas) carries a gibbet whereon hangs the body of a malefactor.

Daniel Waley, Siena and the Sienese in the Thirteenth

Century (Cambridge University Press, 1991), 3

Might the hanged man be one of those highwaymen? Highway robbery will still occur when there is good government; it seems quite incorrect, then, to call a crime like this one of “the horrors of bad government”, not being itself an act of government (though the poverty that encourages it might be).

Rather, what Lorenzetti has suggested on the north wall is that the bad government turns a blind eye to such acts and does not care to remove “the power” of “the wicked”. The good of justice, given to man on the north wall by Wisdom, is – contra that call of the Book of Wisdom, chapter 1 verse 1 – a good that that government does not love.

Having mentioned the gallows in the hand of the Securitas figure, Uta Feldges-Henning notes the inscription running as a border beneath the east-wall panorama:

The inscription on the border again refers to the Justitia of the short wall:

“Turn your eyes, you who rule, to look carefully at her, who is for her glory presented and crowned here. She always gives each his rightful due. See how much good comes from her and how sweet life is and full of peace in the city where this virtue is to be seen, which is more resplendent than any other. She guards and defends those who honour her; and she sustains them. From her light comes the reward of those who do good and she gives to the evil their deserved punishment.”

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace,” 148

In the left hand of Securitas/Wisdom it is indeed an act of justice that we see (even if you condemn capital punishment your argument will be that, in its place, what is demanded is true and measured justice). On the north wall Justice was represented as given to us precisely by Wisdom. If we are coming to understand the picture of things in the Room of the Nine, no confusion is incurred by this multiplication. The virtue of Justitia (including the love of Justice enjoined by the Book of Wisdom) is a part of Wisdom; thus the various personifications superimpose: Justice is Wisdom. Likewise (and in the way we have discussed) Securitas is Wisdom, or more specifically a benefit of those devoted to Wisdom. And also Prudentia is Wisdom, Caritas is Wisdom, etc.: the virtues on the north wall are all divine features. Thus the “her” and the “she” in the inscription all refer to Wisdom as much as to these other things. When the words “this virtue” tell us that the figure referred to is a virtue, we have reason to think of

The virtue of Justitia (including the love of Justice enjoined by the Book of Wisdom) is a part of Wisdom; thus the various personifications superimpose: Justice is Wisdom. Likewise (and in the way we have discussed) Securitas is Wisdom, or more specifically a benefit of those devoted to Wisdom. And also Prudentia is Wisdom, Caritas is Wisdom, etc.: the virtues on the north wall are all divine features. Thus the “her” and the “she” in the inscription all refer to Wisdom as much as to these other things. When the words “this virtue” tell us that the figure referred to is a virtue, we have reason to think of

Justice, a virtue depicted on the bench beside the figure of Common Good,

but also

Love, i.e., Charity, the theological virtue that is love of Wisdom, and is love of Justice, a love inspired by Wisdom (Love is the virtue depicted in the highest place above the figure of Common Good).

Those who have inherited the Kingdom, then, move in a realm in which the perfections relevant to governing, such as these, become gradually clearer – or rather, in which our own suppositions about just, or prudent, or faithful acts are gradually revealed as what they are: conceptions beholden to falsehoods or riddled with defects. For instance, in medieval Siena

sodomy was punishable by a fine …, but if this was not paid within a month the offender was to be hung up ‘by his masculine members’ in the market-place.

Waley, Siena and the Sienese in the Thirteenth Century, 68

This was an act of justice, but did it perhaps mask hatred and contempt.

An inscription that is part of Lorenzetti’s fresco underlines the importance of

giving to the iniquitous due punishment”,

Chiara Frugoni, A Distant City: Images of Urban Experience

In the Medieval World, trans. William McCuaig

(Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1991), 148

but how do we understand what is due? Often defectively, until an experience of beauty reveals the actually due punishment, contrasted with the ugliness of the cruel punishment. Much as the councillors in the Room of the Nine are surrounded with images of these transcendent qualities, those who dwell in the Kingdom live among the originals of these qualities. Those who grow in the knowledge of Wisdom free themselves from rival loves and willingly see their own defective estimations of justice exposed by her, “For she is the brightness of the everlasting light” (Wisdom 7:26).

Where does one go, to take up the project of politics, to be trained in its judgements? We must enter the Kingdom, and, said Jesus,

the kingdom of God is in the midst of you.”

Luke 17:21 ESV

3 | The one successful politics

This means that the project of politics, the Christian politics, is always at hand and indeed is always successful. If this seems implausible that is because the meaning of this claim is still too vague – or because the standard mundane framing is being applied (politics as human action). The politics of the Christian begins when it rejects that framing; Christian politics is successful because it is divinely powered, because it is the choice of what can be successful.

It has to be stated that this Christian politics is not always successful at bringing the land into its ideal state. When we come to the panorama of Siena in the Room of the Nine, in fact, we are faced with a quite pivotal question: what does this image show us? Are we being shown the goal of the politics or the ideal?

We will not see the difference, until we catch the message of the politics presented in this room. Instead we will think these things collapsible one into the other: the goal of the republic is to attain the ideal – which is just what all the scholars presume. They do so quite naturally, in that our understanding of politics is, simply, goal directed: ‘here is what our government will do’ (the difference being that today we are Machiavellian pragmatists while medieval politicians had stars in their eyes).

But the Christian politician, the Christian understanding of politics that we see in this room, divides itself from that view, as the vital alternative. The goal of achieving the ideal (or achieving something less and more matched to our powers) is one thing, and devotion to the ideal – to the image of the Heavenly Jerusalem, to Wisdom,

For she is … the image of [God’s] goodness”

Wisdom 7:26

– is something else. The image is more real than the fantasy, the political promising, because the beauty of justice (and all the beauties revealed by Wisdom, which we will note down shortly) we can see before us, shining with the brightness of the sun (Wisdom 7:29). Between the sun and the bright promise of (billboard) ‘A better future’, a Christian rejects the fantasy.

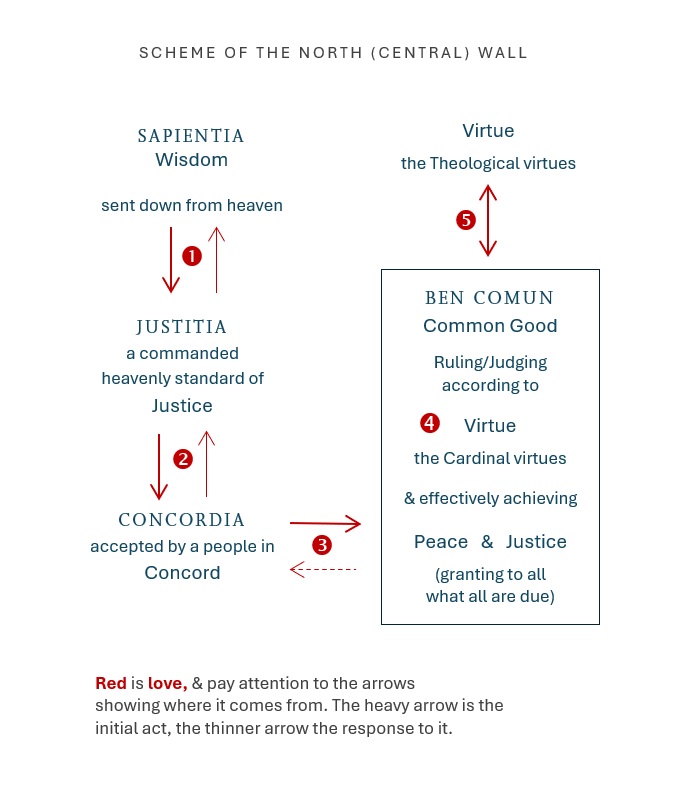

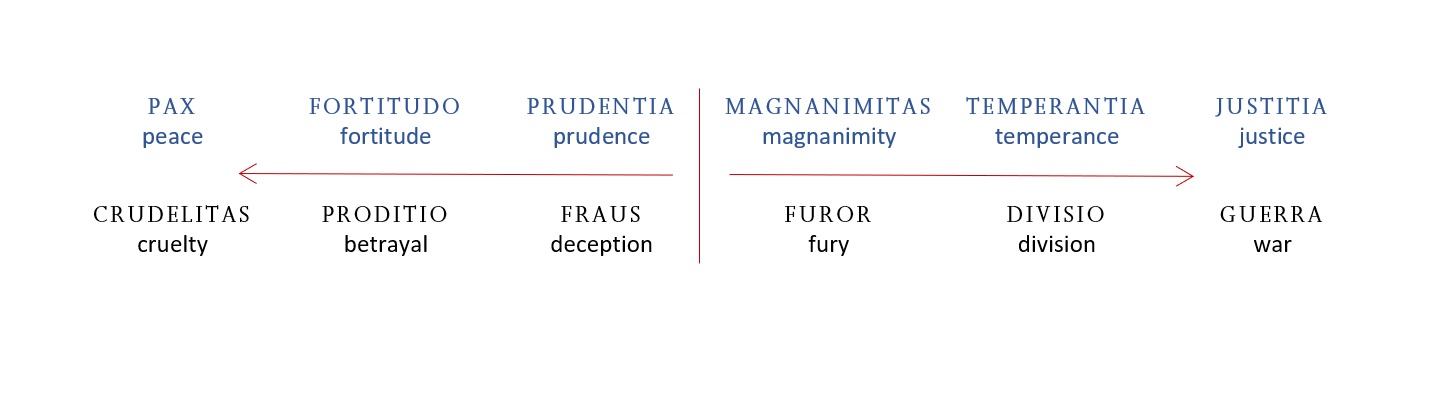

According to the outlook presented in the Room of the Nine, the Siena depicted on the east wall is indeed realizable, but not by governors. It is the common good, realizable only commonly (by the people, roughly as a whole) – if the people unite themselves with God. If instead they listen to men, they will bring about some (perhaps less harrowing) form of the west wall, but a world of misery nonetheless. (Pick your favoured combination of cruelty, betrayal, deception, fury, division, war. Correct, there isn’t one.)  But the only path to what is depicted on the east wall (does it depict ‘The effects of good government’?) is engagement in the true politics, which is fidelity to the ideal. We shall have to specify a little better (as the fresco does) what that business of fidelity involves. Suffice it to say it is not preoccupied with ‘effecting the ideal city’ except by way of loving that ideal, and in these remarks you see the pre-eminence of Fides and Caritas marked on the north wall. But it is very clear, as well, that we are talking also about Spes, hope; a perfected Siena is realizable, not by governors, but to the extent that the people reshape Siena in this image, by the means the room sets out: entering into the project of Christian politics, the work of politics, which is the love of Wisdom.

But the only path to what is depicted on the east wall (does it depict ‘The effects of good government’?) is engagement in the true politics, which is fidelity to the ideal. We shall have to specify a little better (as the fresco does) what that business of fidelity involves. Suffice it to say it is not preoccupied with ‘effecting the ideal city’ except by way of loving that ideal, and in these remarks you see the pre-eminence of Fides and Caritas marked on the north wall. But it is very clear, as well, that we are talking also about Spes, hope; a perfected Siena is realizable, not by governors, but to the extent that the people reshape Siena in this image, by the means the room sets out: entering into the project of Christian politics, the work of politics, which is the love of Wisdom. But the east wall does not show us ‘the effects of good government’ understood as what government produces. Making this happen is simply not the project of this politics and those who profess it, because that is a plan made to fail. Worse, it is an inherently self-contradictory ambition, for the reason that it must create injustice and betray its actual purpose.

But the east wall does not show us ‘the effects of good government’ understood as what government produces. Making this happen is simply not the project of this politics and those who profess it, because that is a plan made to fail. Worse, it is an inherently self-contradictory ambition, for the reason that it must create injustice and betray its actual purpose.

A land coming into its ideal state is something achieved by the way its people live – or, more precisely, the way its people live is that actual achievement, not the means by which it comes about: the ideal state is the ideal way of living. Such a thing is achieved by people willing to live in that way, choosing that way of living because in such a life their lives have meaning. That choice, the substance of that way of life, is something that politics has virtually no involvement in.

The projects of political action (the things that governors and legislators can do) might influence that way of life in a significant manner (removing barriers to that way of living), but politics can never influence the will of the people to live in one way or another except in the most limited manner – unless the politician begins to instil fear. In doing that (we are looking back to the west wall) politics has simply given up the objective of the ideal state, the common good. Attempts to actually control the will of the people (by fines or threatened violence) produce injustice, and where there is injustice there is no ideal state.

If the perfection of the ideal state is to be sought (not betrayed and simply traded away for something achievable) then the desire to create such a state by political action has to be given up. Notice that this ‘Christian’ politics is a politics that is faithful to its own spirit, the spirit actually animating it, in the love of justice. Surprisingly, we can now grasp the point of something we had passed over without comprehension: the “antiquising” treatment, noted by Polzer, of the figure of Wisdom. That imagery, we saw in the last segment, is from classical statuary; why employ it?

Human beings, as Augustine and Aquinas explained, are in touch with Wisdom naturally –

The wisdom … [called] intellectual virtue … is attained by human effort,

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II-II, question 45, article 1

by a God-given power of mind that opens us to wisdom. All men love justice, which Lorenzetti portrayed as a gift of Wisdom; it is a gift given to all men. The pagan notion of the republic originated in wisdom, given to all. All human politics (if it is good) is driven by fidelity to its deepest motivations, which include love of the good of justice. (We do not, in this at least, have a distinctly Christian element of politics. The distinctively Christian element concerns how just, prudent, courageous, etc., acts are decided – not our focus here: we have quite enough to look at.) On the east wall, therefore, we are shown the spirit of all politics, which is Wisdom, revealing to men the goodness of justice.

Thus the Christian politics that I am describing is simply human politics: it is politics faithful to its essence, its source, which is the good that animated it from its very start – which it betrays when it becomes ‘pragmatic’ or ‘realistic’ (turning away from its essential principle to focus on ‘doing good’, getting done ‘the good that we can accomplish’). These two claims are both false. It is neither pragmatic to undermine justice, nor realistic to give up the ideal and settle for a hidden tyranny. To say that medieval politics had stars in its eyes for navigating by the very perfection that is the inspiration of politics itself is completely absurd.

The objective is the ideal: not realizing the ideal but continuing to honour it, to love it, and to hope in the promise of its source in Wisdom, which is “the image of [God’s] goodness”. Not to betray the ideal, a governor must bind himself to the highest thing and accept the actual task that dedication to justice hands him. 4 | Image of the ideal – the heavenly Jerusalem

4 | Image of the ideal – the heavenly Jerusalem

I have asked, what does the panorama of Siena show us: the goal of the politics or an image of the ideal? I answered the latter. Uta Feldges-Henning reports that the teacher of Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, claimed that seven qualities mark the city of the Heavenly Jerusalem:

unanimitas (civium unitatem) | “unity of the citizens”

securitas | security

pax | peace

novitas quam habet per dotes | “renewal by means of gifts” or “endowments”

gratiae infusio | infusion of grace

bonorum operum multitudo | “the multitude of good works”

virtutum decor et compositio | “decoration of virtue”

Albertus Magnus, In Apocalypsim B. Joannis Apostoli,

cited by Uta Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme

of the Sala Della Pace: A New Interpretation,”

Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 35 (1972), 160

She then writes,

All these requirements are fulfilled in our fresco.”

That is, we could see Lorenzetti’s depiction of the city as Siena in something like the ideal condition. An instance of the Heavenly Jerusalem? That depends on what this expression means, which we encounter in a passage of Hebrews on the Kingdom of God.

But you have come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to innumerable angels in festal gathering, and to the assembly of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven, and to God, the judge of all, and to the spirits of the righteous made perfect, and to Jesus, the mediator of a new covenant, and to the sprinkled blood that speaks a better word than the blood of Abel.”

Hebrews 12:22–24 ESV

(Note how the issue of justice lurks here.) There is no need to settle what the Heavenly Jerusalem is; it is enough to picture it as a “city of the living God” understood as a city in which “the image of his goodness” (Wisdom 7:26) is present: is as visible as a living beauty. That is the Siena depicted here, under an image of Wisdom herself. It is a city in which the politics of the Kingdom is embraced, though not by all (as noted, crime occurs here).

The seven qualities of such a city that are listed by Albertus Magnus could not, perhaps, all be expressed in a portrait of a physical city such as Lorenzetti gives us. Could these qualities, if present in a town (concordia, grace, works, virtue, etc.), all be seen as you walked through it? Or should we turn the question around: is it, rather, their absence that would stand out? Is a land in the grip of death the perfectly apparent condition? I have already noted, essentially, how visible, on the west wall, is the absence of any gratiae infusio working on the souls of the roaming agents violating the citizenry. A land free to flourish is a land released from the grip of death.

Feldges-Henning, in any case, does not turn only to the landscape for evidence of the seven features; the first she finds on the north wall, the second there and in the panorama:

the ‘unity of the citizens’ is represented by the procession of the twenty-four figures, who are led directly by Concordia. … Pax is assigned to the series of virtues as a personification and, in a figurative sense, is to be seen in the peaceful life of the city and the country….”

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace,” 160

And what is that peaceful life, that ‘ideal way of life’ chosen by the inhabitants, made visible in the fresco? In the town, she writes,

it is possible to make out the following activities in detail (from left to right): the arrival of a crowned lady at the head of a procession of riders; men gambling in the tavern;

a clothes-mender; … a goldsmith’s workshop, and various other trades; two men on horseback with tall hats; cobblers; a teaching scene; the selling of food and spices;

the transport of wood; textile workers …; a man driving an ass; a shepherd; peasant women with their wares. On the upper edge of the picture, finally, there are masons at work building a house.”

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace,” 160

She locates the next two qualities as follows:

Renewal by means of gifts is expressed by the kneeling knights, who present their goods to the commune,”

an illustration of communal charity shown just to the right of the figure of Ben Comun on the north wall.

The ‘influence of divine grace’ is indicated by the three theological virtues, hovering above the head of Ben Comun….”

I have already noted how we see no “influence of divine grace” in the actions that stand out on the north wall. What is striking, actually, about the people on the east wall is how busy they are, how contented to go about their business. No one is upset, harried by an unreasonable manager. No one is sitting around wondering what to do with his life, or looking into his phone for something to give his moments meaning. The next quality she notes is

The multitude of good works[, which] refers to the population, for the execution of the ‘artes’ was not only seen as useful, but also as morally good.”

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace,” 160

The artes mentioned are the “mechanical arts” or artes mechanicae, which

Hugh of St. Victor, … in the second book of his Didascalicon [written in the 1120s], defined [as] those activities which are necessary to human life,”

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace,” 151

especially physical life. Note this feature of the fulfilled city: the people are occupied, and contentedly. They do not find this work uninspiring, inadequately remunerated – refusing to do it (so that willing labourers must be found elsewhere) and drawing on ‘unemployment benefits’ while they send out resumes to land something sufficiently engaging and ‘good for their future’. No one in the city seems to be wandering around, looking for the ‘fulfilment that existence holds out for us’. Thus Feldges-Henning notes that work, in medieval theory, was understood to be “morally good”, to say nothing of “contentment”.

Godliness with contentment is great gain, for we brought nothing into the world, and we cannot take anything out of the world. But if we have food and clothing [both ‘needs’ give people in the fresco work to do], with these we will be content. But those who desire to be rich fall into temptation, into a snare, into many senseless and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction.”

1 Timothy 6:6–10 ESV

What is visible in the image of Siena is the absence of people ‘plunged into ruin and destruction’ by the ‘senseless desires’ bred by dissatisfaction. When listing the sixth quality of the Heavenly Jerusalem Feldges-Henning refers back to the diagram of the virtues –

The ‘decoration of virtue’, finally, can be admired in all its detail on the short wall”

– but she might have noted what I have just discussed: the virtue implicit in contented people who have had the good sense to say no to fantasy, pleasures they imagine are due them, that are the meaning of life itself.

The one quality we have yet to mention is Securitas, which Feldges-Henning locates in the personification.

Securitas hovers as a genius over the country.”

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace,” 160

Is it visible in the panorama? If it is understood as, simply, ‘security’, we have accounted for that already, as Peace, which Albertus lists as a separate condition. As I have been unable to find his text I do not know what meaning he attached to Securitas, but it is certainly the case that in a city growing in virtue all the needs of the inhabitants are ‘secured’. If there is anything that we would wish Securitas to secure, it is surely what is good.

Richard Ingersoll writes, of Lorenzetti’s image of Siena, that

It is a city of work and exchange that is not immune to play or children and seems wonderfully free from conflict….”

Richard Ingersoll, cited in “Ambrogio Lorenzetti:

the First Panorama,” at the blog The Art of the Landscape

When we turn to

the country the emphasis is on agricultural work: viniculture, reaping, collection and threshing of corn and transporting it to the mill, sowing, ploughing and hoeing. Then comes livestock husbandry, represented by a shepherd with a flock and a peasant driving his pig to market in the city. Hunting is also portrayed: falconry, … fishing and bird-catching.

On the road in the foreground, there are several representations of the transport of goods, as well as a group of nobles riding to the hunt, passing a wayside beggar.”

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace,” 150

The road is a prominent feature, and this was a concern of the city government.

Proper guard and protection of the highway was a normal function of government in the Middle Ages and it was natural that the oath taken by Siena’s leading official … should include the promise ‘to govern the highway throughout the territory of the city, to the honour of God’…. ‘Clerks (clerici), pilgrims, merchants, and others travelling on the highway or other roads of the city or its sphere of jurisdiction must be defended and protected’, and any one harming them must be punished,….

Waley, Siena and the Sienese in the Thirteenth Century, 3

That the performance of this function was expressly understood as a ‘fitting offering to God’ is a reminder of the political outlook I have tried to describe. The honour of what is most deserving of honour (a form of the love of Wisdom) is an essential thing, is a part of the motivation; the social benefit is an effect of this. It is not that one is primary, the other secondary: the love of the good in the work is a form of the love of God. It is that if the former is the objective, the latter will be done, whereas if the latter is the objective, not even it may be done; some greater commitment may stifle it.

The unprotected roads on the west wall bring about a very different life than the life in evidence here.

The countryside is well tended with villas and farms … and everything looks well watered. The allegorical nature of the picture is made clear by the presence of farmers planting in one part of the landscape and harvesting in another.”

Ingersoll, in “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: the First Panorama”

US & THEM

I said earlier that when we turned to examine the east wall’s image of town and country and re-entered concrete life, the emotion we felt looking at the opposite wall – an engagement we then, perhaps, lost when turning to the ‘diagram’ of the north wall – would return. Centuries after it was completed Lorenzetti’s painting can ask us a question, a perhaps uncomfortable one. We no longer mow with scythes or travel on horseback, etc., but with all the appropriate changes made, is our town, our homeland, in the condition depicted on this wall? Are these living conditions ours – or are the goods that Lorenzetti depicts here significantly denied to us, in a way that it is painful to register?

It would appear that we do not even have Siena’s conception of goods. All seven of the features that Albertus identified in a “city of the living God” can be called goods – reflections of God, who would be honoured by acts performed to secure them (provided that those actions issued from the pursuit of Wisdom and so had a claim to be called ‘done to the honour of God’). All are desirable effects of political action.

Today, for instance, do we have Concordia or the “unity of the citizens”? In the cityscape of Siena we see it in the absence of conflict noted by Ingersoll, who adds,

It is quite interesting that unlike renaissance views of the ideal city, Lorenzetti’s ideal city is boisterously full of people, dense to the point of bursting with a heterogeneous variety of buildings….”

Ingersoll, in “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: the First Panorama”

In a city, discord never hides; it is always in the open, in harsh words and disgusted faces. It is not just that discord, instead of concord, is now counted the norm by modern realists, it is that discord is a protected condition, a sign of what is counted healthy human society. Anything that threatens to advance a “unity of the citizens” is regarded with suspicion, as veiled hostility, a threat of injustice. Concordia is not even a good.

Are we prompted by the imagery in this room to note that our state is more notably marked by the evil conditions Lorenzetti has itemized on the opposite wall, conditions sowed by the creed of “ELBENPROPIO”?

If we are pained by the knowledge that the life on the east wall is not ours and is far from us the one thing not to do is to ignore the message implicit in the politics  of the Room of the Nine and mount a plan to rescue Western civilization. If there is any truth to the claim that, for instance, the Irish saved civilization, they did it only as part of an entirely different preoccupation: the love of Wisdom.

of the Room of the Nine and mount a plan to rescue Western civilization. If there is any truth to the claim that, for instance, the Irish saved civilization, they did it only as part of an entirely different preoccupation: the love of Wisdom.

Or, to put it in another way, if there is anything from our tradition to bring back, it is a single understanding of why we are living: CARITAS.

5 | Philosophia, the successful pursuit

The political project, within Christianity, is the process of the lover drawn to the beloved by actual perfections – that is, and without any stretching or playing with words, it is Philosophia, the love of Wisdom.

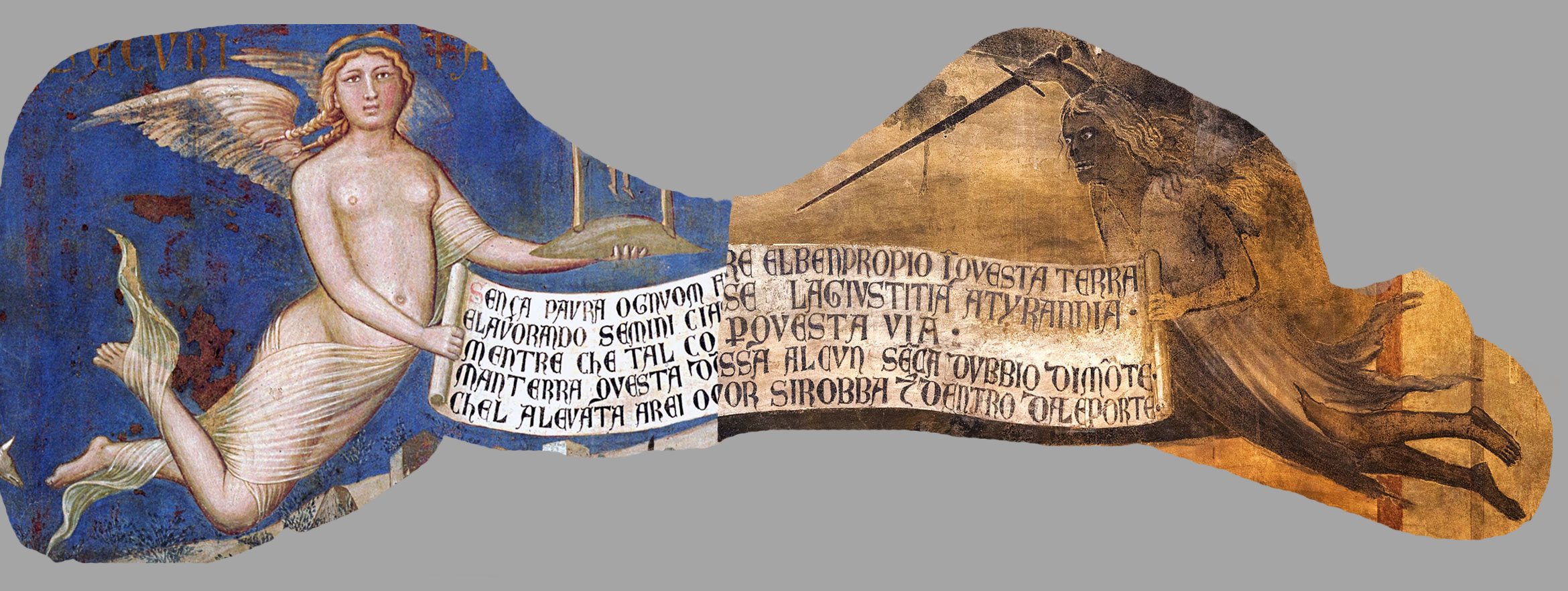

If we look, in a closing summation, at the diagram of the north wall, paying attention this time to the dynamic of giving that is charted there, that chart marks out a cycle of reciprocated love.

At {1} Wisdom passes down to men a conception of Justice as equity (proportionality), a standard by which men can live together in peace. Why does she do so? For the welfare of men; it is a principle given in an act of love.

All men, Christian and atheist, pagan and modern, respond by seeing the supremacy and rightness of this standard. Why do men, all men, cry out for justice when it is denied them? Out of love. Justice is loved.

Then at {2} the divine gift of Justice gives men Concord. It draws them together as friends, as a people moved by the same love of justice. It is a gift of meaning. Given why? Again, out of love for men, to give men meaningful lives.

The people respond by adopting a common cause, united in the project of maintaining Justice among them (maintaining this lady over them | “Manterra questa donna in signoria”). Why? For love of her transcendent supremacy, and loving at the same time the shared love of their project, loving their ‘fraternity’ in that cause, loving the brethren to whom they are bound together in Concord.

Then at {3} Concord gives them a common project – a cord to hold onto, meant to lead them to the fulfilment and happiness of every member of their society (achieving the common good). Why? For the happiness and fulfilment of men, which love of men desires all men to have.

The people respond by taking that cord, governing in such a way as to fulfil the cause that had united them in Concord. Why? For the love of the good in doing justice and having fulfilment.

But this response is minimal. There is a full and unhindered response to the idea of justice; the love for the idea that all should have what they are due is genuine, but exactly that result is prevented by the way these men live, the men holding the cord (governing) and those in their society who support them (sharing their love of justice). What else they love prevents it.

The loves in men conflict. To deliver what they claim to love they would have to say no to other loves (the action of Temperance). As Augustine explained, the terms of the love professed by these men all through this chain thus far, from {1} to {3}, are exclusive terms: they profess to love what deserves love and do love it intellectually – but to love it truly, in deed, means not secretly opposing the thing they love.

Little children, let us not love in word or talk but in deed and in truth.”

1 John 3:18 ESV

But they oppose it; they act in such a way as to drive justice out of their society when it interferes with the enjoyment of other things they love – and “in truth” love more, in this instance and that, where they are faced with the choice between the one and the other, and what they love more is what they choose.

The question is always,

Now do I love Thee alone, follow Thee alone, seek Thee alone; now am I ready to serve Thee alone…?”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Foley, book 1, ch. 1; 22

The answer is always No, and this answer imperils the entire ‘plan’ of politics, every plan, no matter how oriented it is to actual goods.

What these men have here (at {3}) embarked on is anything but a successful pursuit. The barrier to success is the most formidable one of all, because it is in themselves and unrecognized. They ask themselves whether they love justice, and take note of all the red arrows of love they send it, and believe that they do (concluding, inevitably, that complaints of justice are either fanciful or involve injustices caused by someone else – in either case, the problem is other people).

There is only one way out of this impasse, and Lorenzetti and his fellow political theorists chart it in the Room of the Nine.

[]

If we think of the rectangle in our diagram (at {4}) as a human soul, the soul of this citizen is already in a condition resistant to what he or she is professing to do, in common cause with other agents of justice.

The trouble here has a diagnosis: it is bondage in the soul to the very attractions that deny justice. That is, it is a secret adherence to the very law of tyranny, “ELBENPROPIO” – ‘the good’ (elben) of the ‘self’ (propio).

That diagnosis singles out a cure, but whenever that cure is identifed as ‘virtue’ there is good reason to doubt that the illness has been properly understood. To tell people that virtue is the solution to the problems of society is to emulate an idiot: the ‘doctor’ who writes, as his prescription, ‘Health!’. (What good can it do to recommend a drug that the patient’s disease renders her unable to process? – It is a deficit of Temperance, an inner force that prevents Temperance, that is the disease.)

As Etienne Gilson notes,

To fall, man has but to will it; but a mere desire to rise from that fall is not enough to enable him to do so.”

Étienne Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of Saint Augustine,

trans. L.E.M. Lynch (New York: Vintage, 1967), 153

In the last segment I did what I could to explain how, if ‘virtue’ is the answer, it is not the cure, it is not the prescription; it is what the cure restores. The cause of injustice is people who may love justice but lack the ability to deliver it, because of rival and not easily dislodged commitments. Those things are what these people are living for.

At this point our diagram connects with another part of the room, the west wall, where the three great forces that prevent virtue are named.

Avarice, driven by the love of wealth (that fading good), can derail every sort of virtuous impulse. (The judgements made by the man attempting to be Prudent, for instance, are skewed by the importance to him of personal gain, the desire to protect his ‘lifestyle’.)

Vainglory (hunger for attention) and Pride (unwavering belief in one’s own judgement and decency) also impair the stirrings to virtue. These passions, each in their own distinctive ways, influence what such people believe to be virtuous acts.

We are talking about the task that, at {3}, is handed to the people by Concordia/Wisdom. Devoting oneself to justice, in a community of caring people, hands a person an actual task. What is that task? It involves people in what the ancient and medieval worlds called the work of liberty: liberation from bondage to the very attractions that deny justice – from exactly those loves that attach men, secretly and within their hearts, in this way or that, to the creed of tyranny. – But how, with such a heart, will they themselves manage this?

The answer is a healing that again comes from outside.

Libertas is a resultant of the action of God’s grace.”

Vernon J. Bourke, in The Essential Augustine,

ed. Bourke (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett, 1974),176

People lacking virtue in these ways have to be rescued, and the same entity that initiated every good thing in the scheme we were following – out of love for man – intervenes again (at {4}) to heal the human soul. Wisdom, said Augustine, “fulfills the function of a physician”. Why? Out of love for man.

We return then to the issue of man’s response. Under this care from God a man might not respond (not seeing the transcendent good as greater than the things he loves – not loving it). Yet he might respond to God’s revelation of transcendence and turn from the unworthy loves. If he does the former it will be out of love for the lesser thing, out of failure to see the glory of what he has been shown, or some such thing. If he does the latter it will be out of love for what he now has seen. He has been given Wisdom and can love her.

… wisdom is a gift of the Holy Ghost.”

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II-II, question 45, article 1

The double arrow at {5} is a way of showing that this very power of response is itself, in some way, a gift of God. The love sent down to men and the love returned to God is, in a sense, all God’s gift to men; those who do respond with love are, in a very significant way, made to do so – but it is all voluntary: it is genuinely human love (chosen love). But because human love and divine love (also chosen) are here coming together it is marked with a single arrow. Man is being divinized, united with God.

From the very fact that wisdom as a gift … attains to God more intimately by a kind of union of the soul with Him, it is able to direct us not only in contemplation but also in action.

Aquinas, Summa, II-II, question 45, article 3

Love is supreme. By the gift of the Theological virtues (as was discussed here) men are enabled to love God, in word and in deed.

At the top of the pyramid [of the Theological virtues] is Charity; she presides over the others. Lorenzetti gives charity the highest position which is perfectly in line with pre-humanist thoughts harking back to Paul (1 Corinthians 13:13). Latini writes:

‘Even if someone seems good in faith and in works, I say that he does not have any virtue if he is deprived of charity and of love towards his fellow men’.”

Hanneke van Asperen, “The Virgin and the Virtues:

Charity in Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Representation of

Good Government,” Artibus et Historiae 37:73 (2016), 58

The answer to whether he has such love for men lies in what he loves.

Further, by inspiring man to love Wisdom and thus orient himself by the glory of God, God loves man as man. The panorama we are shown of the ‘well-governed city’ is simply an image of the city created by those who are so-oriented. People being divinized are ever more able to live as they are meant to live, and do as they have resolved to do, and promised each other to do: to be just.

[]

If the healing by Wisdom is not rejected, if the gift of Wisdom is not refused (as it can be), ask, once again, about the prospect of success of this project that began as the love of justice. What was born in that way – or, let us say, what began as a project of politics, as the effort a person makes to bring Siena into her glory – was undermined by that person, thanks to the state of his or her soul, the character of its loves. Unless the soul could heal itself, that project would founder; all that it would deliver was changing colours of tyranny in a self-reinforcing system. But politics was not the name of the overall event.

The being that initiated the scheme of gift and response that is laid out on the north wall of the Room of the Nine has continued what it earlier had begun, and the politics that had foundered as merely human action was rescued as philosophia, love of Wisdom. The west-and-north-wall diagram connects with the entire east wall, which announces that, As love of Wisdom politics succeeds and justice can be done. There is hope of a remade city. Even if this healing is undergone by only a component of the populace, there is some hope of living in an ideal city.

Lorenzetti’s east-wall fresco may represent Siena in an ideal state; this is a state that no group of leaders and citizens (through their judgements and deeds) is equipped to realize. The project of politics conceived as moving Siena into a state of perfect flourishing cannot succeed, unless it avails itself of the agency of God, acting on man, through the one form of relationship in which man is freed from his tendency to tyranny.

But ‘on man’ is too generic. In this project it is the political actors, the ones making the change, who are transformed (the governors, the people who elect them). It is their ways being purified in a fire of love in which the everyday impulse to tyranny is burned away – it is that that brings about the flourishing state, little by little.

It must also be apparent that in this politics there is no scope whatever for use of the word ‘them’. The state may be ravaged by a true enemy, doing the people actual harm – actually perpetrating atrocities – but the only step of progress toward good (to peace and to justice as effects of political action), here as everywhere, is driving out the impetus to tyranny in one’s own soul. It is only there that there is any access to tyranny, it is only there that we lay hold of divine power.  It is grotesque to replace that fact with a rehearsal of human history: the defense of some cruelty (CRUDELITAS) we have visited upon ‘them’, of the war (GUERRA) we are now raining down on them, for rape and murder they visited upon us, … to repay injustice in the past done to them, … done in a ‘righteous’ response to a great evil done to us (e.g., Gaza—October 7—Occupation—Holocaust). It is by pulling up the root of tyranny where God gives us power over it that we walk out of the hands of Death.

It is grotesque to replace that fact with a rehearsal of human history: the defense of some cruelty (CRUDELITAS) we have visited upon ‘them’, of the war (GUERRA) we are now raining down on them, for rape and murder they visited upon us, … to repay injustice in the past done to them, … done in a ‘righteous’ response to a great evil done to us (e.g., Gaza—October 7—Occupation—Holocaust). It is by pulling up the root of tyranny where God gives us power over it that we walk out of the hands of Death.

This means that the project of politics ceases to be production, a work of human doing, and itself becomes

the pursuit of wisdom,”

Augustine, Soliloquies, trans. Foley, book 1, ch. 11; 39

which is the only way of producing what we entered politics, quite rightly, to produce. Siena in her glory is not a project. What we are told by the Christian authors of this cycle of images is that it is an effect of keeping Wisdom, in all her transcendence, “in the midst of” the people, and that is not an executable act.

Might the Sienese, under the guidance they gave themselves, have come to enjoy justice? We will never know, thanks to injustice.

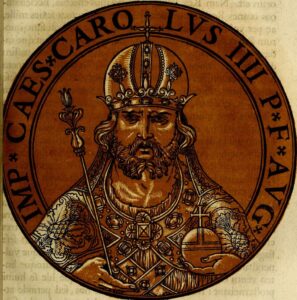

The regime of the Nine fell in March 1355 when the arrival of Charles IV [Prague-born King of Germany and King of Bohemia, who became Holy Roman Emperor in that year – note the cross on his orb] with a force of one thousand knights sparked an uprising by disaffected magnates and a vindictive crowd. There were reports of looting and arson. The official records on which the Nine had set such great store were destroyed in the emperor’s presence, and the shattered chest containing their electoral lists was dragged through the streets on the tail of an ass.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 58

Thanks to injustice? The Sienese explained what the great problem in this is. It is not the termination of the project to ‘keep a republic’; it is the prevalence of tyranny, in the furtherance of ‘wise’ political acts done for some other reason than submission to the actual presence of Wisdom.

Artist

Ambrogio Lorenzetti (active 1319–1347)

Date

1337–1340

Still in its original site in the Room of the Nine (Sala dei Novi) of the Palazzo Pubblico Comunale, Siena

Medium

Fresco

Photo credit

Steven Zucker, Smarthistory