Ideal government IV | Lorenzetti’s political manifesto

In this essay,

• THE OVERALL SCHEME OF THE ROOM OF THE NINE

• INTO THE DIVINE

• THE ODDLY INVISIBLE CHRISTIAN MANIFESTO

• MODERNISM’S ‘BUT THIS IS COMPLETELY IMPRACTICAL’

• MISUNDERSTANDING CHRISTIAN VIRTUE ETHICS

• THE APOSTASY OF ‘CAN-DO VIRTUE’

• MORAL PLUS THEOLOGICAL VIRTUES

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | The overall scheme of the Room of the Nine

We have been looking at the medieval conception of good government set forth on the walls of the Sala dei Nove in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico – expressly laid out there, says political philosopher Maurizio Viroli, to

explain to the magistrates and the citizens the principles of good republican government.”

In that era, prior to the Renaissance, republican ideals were being revived in a set of treatises issued by Italian thinkers, some of which we have cited (the Livres dou trésor written around 1290 by Brunetto Latini). Viroli explains that these

treatises on government helped to spread the beliefs of republican religion.”

What does he mean by that? In that choice of words he is not mocking medieval republicanism, but noting, rather, that

the message that came from the walls of the city government’s most important halls was political and religious at once.”

In mentioning “the walls” he is referring to the Room of the Nine and the frescoes we are examining.

Even more effective [than the books articulating republican thought] were the images that expressed those beliefs. Whereas the concepts expounded in the treatises appealed first and foremost to reason, paintings struck the eyes, and from the eyes touched the passions.”

Maurizio Viroli, “In Defence of the City-State,” Engelsberg

Ideas blog (10 March 2021)

You might disagree. If you have been following our tour you might suggest that the engagement of emotion was quite markedly dampened by the north wall’s detour into ideas – by its shift to what I have called a diagram. But emotion was there at the start of the tour and it will return before we finish.

In this room the artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti makes a progression from the truly disturbing wall of tyranny and the desolation it brings to town and country (the west wall, examined here) to, on the north and central wall, the truths denied by or dismissed by every tyrant – truths concerning both justice (part II) and the role of particular virtues in securing the common good (part III).

On this central wall there is very little drama, at one level because there is very little interaction between figures; the presentation of individual seated virtues replaces it (recall, by contrast, the vice of Cruelty on the west wall, shown torturing an infant). But why no interaction? This lack of drama had a significance. In the schemes of imagery developed in the 13th century for the cathedrals,

On this central wall there is very little drama, at one level because there is very little interaction between figures; the presentation of individual seated virtues replaces it (recall, by contrast, the vice of Cruelty on the west wall, shown torturing an infant). But why no interaction? This lack of drama had a significance. In the schemes of imagery developed in the 13th century for the cathedrals,

the contrast between the majestic repose of the enthroned and inactive virtues and the enacted scenes of the vices below was one of the most effective new conceptions of the cycle.

the contrast between the majestic repose of the enthroned and inactive virtues and the enacted scenes of the vices below was one of the most effective new conceptions of the cycle.

R. Freyhan, “The Evolution of the Caritas Figure

in the Thirteenth & Fourteenth Centuries,”

Journal of the Warburg & Courtauld Institutes 11 (1948), 70

(For example, on the cathedral at Chartres, completed a century earlier, shown at left: the virtues sit serenely, as changeless reflections of God, while the vice scenes contrasted with them show human beings suffering injury – like the fall incurred by pride in the scene with the horse at bottom.)

INTO THE DIVINE

That is, what the central wall presents is an image of the ‘mind of God’, which the Sienese were invited to participate in, in the way they governed and lived. If to us this sounds peculiar that is because our understanding of Christianity has been gradually faded since the day of Lorenzetti to conform to some more acceptable conception of ‘normalcy’. We need to de-bleach our picture, with the agent of Scripture.

The entire layout of the north wall is summed up in a single verse from an epistle of Peter:

His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness,….”

2 Peter 1:3 ESV

(‘All things’ would include a conception of politics, the very conception that is viable.) To be ‘granted’ what pertains to ‘godliness’ seats the person who accepts what is granted in divinity (as “Ben Comun” or the common good, here, sits surrounded by the perfections of God). If there is any doubt about this (and of course there is), read on, as Peter explains that this is done

through the knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and excellence,….”

2 Peter 1:3 ESV

We will return to what is meant by “knowledge of him”; the great claim made in this is that we are ‘called to’ God’s “own glory and excellence” (this, as we just read, being “granted to us”). In case we still doubt the meaning of what we are being told, as well we might, Peter continues, repeating his claim of the grant or gift:

… by which he has granted to us his precious and very great promises, so that through them you may become partakers of the divine nature, having escaped from the corruption that is in the world because of sinful desire.”

2 Peter 1:4 ESV

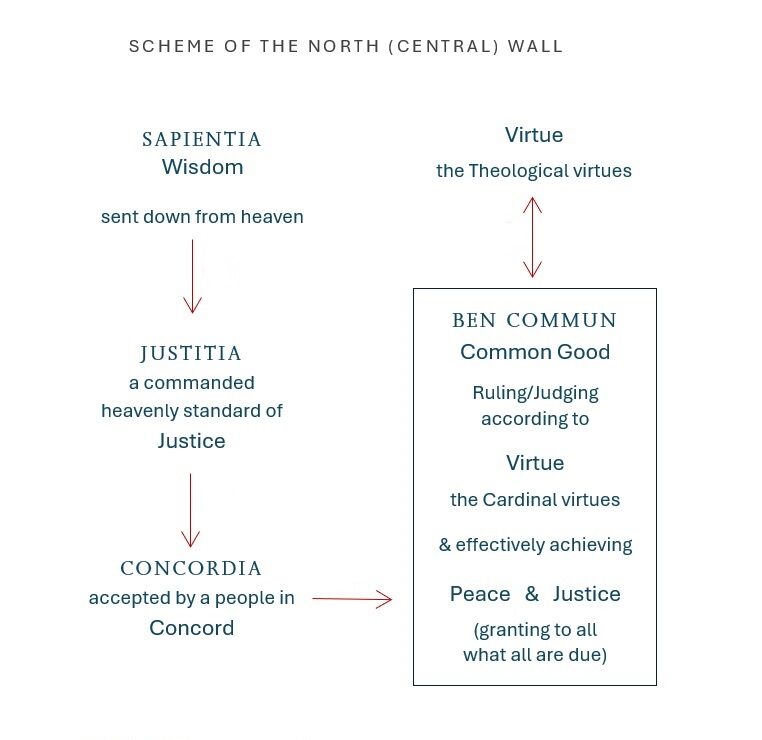

The repetition is therapeutic, to help us accept what seems inconceivable, and in the Room of the Nine this message is applied not just to human beings but to us in the present – nothing is said here about a future in heaven. What the chain of images on the north wall (diagrammed below) announces is that the kingdom of God has descended to earth and we may enter it – and in so doing govern our city in alignment with it. And if we do, then people may ‘escape from the corruption’ that is the cause of tyranny (and there is no other manner of escape). And this occurs by a “knowledge of (an abiding contact with) God” that draws us, by love of God, into His nature as participants in divinity (“partakers of the divine nature”).

The lack of drama that at one level starves feeling is no barrier to feeling if this is the message of that image. It is obvious that Lorenzetti cannot, in the quality of his imagery, measure up to the character of this message, but if the message can be got across even with crude images the achievement will be magnificent.

What sabotages Lorenzetti’s work, however, is the resistance of readers to the message itself. Among the thirteen scholars whose accounts of this room I have read I do not find one who attributes this Christian outlook to the Christian designers of this work, despite the prompts to read it this way that those creators spread out over the wall.

This cycle of images (the name for a united series) has been called

an allegory of the effects of good republican government,”

Randolph Starn & Loren Partridge, Arts of Power:

Three Halls of State in Italy, 1300–1600

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 47

and is commonly given the title,

Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government”

– or, spelled out more fully, these scholars effectively provide a title for each of the three painted walls:

Allegory of Good Government [north wall], Effects of Good Government in the City and the Country [east], and Allegory and Effects of Bad Government in the City and the Country [west].”

Beth Harris & Steven Zucker, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti,

Allegory & Effects of Good and Bad Government,”

in Smarthistory (9 December 2015)

I have no objection so far as this goes, though practically the only allegorical element seems to be the action of the councillors binding themselves to the cord of justice on the central wall. But the personifications that cover this wall (presiding as presences over the activities of the Nine, conducted in this room) enact no allegory; they are meant to signal presences. But there is something entirely missing from all these formulations, and it is the message delivered by the Gospel to the councillors, the substance summed up by St. Peter in the passage related above. The several points of that message that I have already underlined are emphasized in the work itself.

2 | The oddly invisible Christian manifesto

I can address that omission by way of a comment made by Prof. Viroli, criticizing the way that modern political thinkers habitually disparaged these medieval Italian republics. Looking back to Hobbes, Montesquieu, and the American Founders, all of whom were dismissive of these regimes, Viroli writes,

What contemporary scholars, with few exceptions, have not adequately explored, however, is the fact that Italian city-republics produced – and were the product of – a particular kind of Christianity: a Christianity sustained by a religious sentiment that cultivated charity and preached the principle that only a good citizen who loves and serves the common good can be a good Christian.”

Viroli, “In Defence of the City-State”

That is exactly the emphasis, the manifesto-type point. (Every manifesto is a declaration that ‘you are all on the wrong track’.) In this light the image cycle of the Room of the Nine should rather be titled,

The politics of the true Christian: principles and effects of divine and infernal governments,”

or, more expansively,

The principles and effects (in city and country) by which a government proves itself Christian – having ‘entered the Kingdom of God’ (Mark 9:47), into which men are called by Christ, to participate in it, in the “divine power” of “godliness”, as “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:3–4) – contrasted with principles and effects of obedience to the “Prince of this world”,

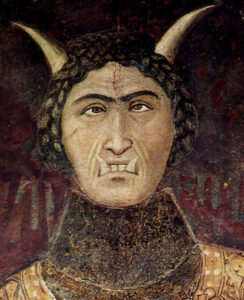

whom we have seen seated on the throne opposite the personified Common Good.

Represented on the walls of this room is the standard by which a truly Christian government is measured. What is the ‘city of man’ if man is the image of God?

As man can ‘image’ God, so could an earthly city become the image of the “the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem” (Hebrews 12:22). Among the scholars, however, scarcely any seem able to count that suggestion a component of the message. Uta Feldges-Henning stands out by claiming that

The government of the Nove is here giving its political credo,…. We see in the portrayal of the city of Siena traits of the Heavenly Jerusalem….”

But she too proves unable to see this as anything more than background, reducing “the world-picture of the Trecento” (the 1300s) to our terms.

The religious component of Ambrogio’s painting is overshadowed by the political; the result of its being commissioned by the civic authorities and its situation in the Palazzo Pubblico. The Sala della Pace [a name used by some scholars instead of Sala dei Nove, giving special importance to the figure of Peace] gives the world-picture of the Trecento: Good Government and Tyranny, virtues and vices, war and peace, and the allegory of Justitia are fitted into the macrocosm with the seven planets and the four seasons. [Here she alludes to the things symbolized in the small medallions Lorenzetti added to the margins of the pictures we are looking at, which I will ignore.] The learning of the time, the seven Liberal Arts and philosophy are set off against the mechanical arts,”

Uta Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala

Della Pace: A New Interpretation,” Journal of the Warburg

& Courtauld Institutes 35 (1972), 160–61, 162

etc. – but not a mention of anything remotely related to the Gospel. In this summation of what the imagery in this room is about there is no Christian manifesto, but that is precisely what the government of the Nine delivered.

To be a Christian government – to govern from within the Kingdom, responding to the call of the ‘good news’ – is to pursue these particular objectives (justice, peace, concord) by the exercise of these particular virtues. It will not be good enough to claim to be a Christian ruler; what you see painted here is the standard by which that claim will be measured (if there is no peace, if there is no justice, your words will be disproved). The Nine publicized this message on its walls not, as the scholars so often observe, because

the government was intentionally making propaganda”

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme of the Sala Della Pace,” 162

but to inform the public that their government had adopted these (divinely imposed) restrictions on its own actions (not the usual boast of propaganda).

Feldges-Henning argued that the propagandizing was meant to calm unrest.

Some years before the commencement of the painting … there had been several uprisings so one can all the more easily assume that the government was intentionally making propaganda,”

but might it be that the unrest was caused by injustice, and that the government was not retreating to advertising but agreeing that that problem was real, and actually foreign to Kingdom rule? Again I quote Viroli:

Only a good citizen who loves and serves the common good can be a good Christian.”

Viroli, “In Defence of the City-State”

The issue here is not just good/bad government but genuine/false Christianity as evinced in political commitments.

The Christian elements present in the image are not just a kind of marginalia (details we should expect when the authors of this scheme were Christians, ‘but their real concern was politics’). What was declared on these walls was both what principles and objectives are central to the government of a Christian people and what visible conditions are the index of their seriousness, their fidelity to Christ, as per his own words:

Wherefore by their fruits ye shall know them.”

Matthew 7:20

It both declared how the Republic of Siena would focus its activity and how those subject to its power could hold the government to account. That is a very particular kind of propaganda, a term whose application to the Room of the Nine is correct in this, its original, sense: what we see in the Room of the Nine is the propagation of an appropriately Christian politics. That this is not the way propaganda is typically understood owes simply to the fact the positive and Christian origins of the term (propaganda fide, propagation of the faith) have been forgotten.

A Gospel message prevails in this room. You shall know the faithfulness of the people of Siena by the way they, in their government (a republican government being a government by the people), satisfy the conditions that God has set for them and do what God requires, so that all the people can flourish. In that the Gospel message was a call to gather up God’s straying people –

Know that the LORD, he is God! It is he who made us, and we are his; we are his people, and the sheep of his pasture”

Psalm 100:3 ESV

– who had strayed for centuries, from the age of the prophets, and specifically in seeing themselves as faithful people (‘Christians’, Sabbath-keepers, etc.) while refusing to heed the shepherd’s call … in governing. Some of Lorenzetti’s imagery echoes the words of Isaiah on “the faithful city” and its opposite.

Ah, sinful nation, a people laden with iniquity, … children who deal corruptly! … Your country lies desolate; your cities are burned with fire; … in your very presence foreigners devour your land; it is desolate,…. Give ear to the teaching of our God,…! “What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices?” says the Lord; “I have had enough of burnt offerings…. When you come to appear before me, who has required of you this trampling of my courts? Bring no more vain offerings; incense is an abomination to me.… Your appointed feasts my soul hates;…. When you spread out your hands, I will hide my eyes from you; even though you make many prayers, I will not listen; your hands are full of blood.… Remove the evil of your deeds from before my eyes; cease to do evil, learn to do good; seek justice, correct oppression; bring justice to the fatherless, plead the widow’s cause…. If you are willing and obedient, you shall eat the good of the land; but if you refuse and rebel, you shall be eaten by the sword; for the mouth of the Lord has spoken.”

How the faithful city has become a whore, she who was full of justice! Righteousness lodged in her, but now murderers. … Your princes are rebels and companions of thieves. Everyone loves a bribe and runs after gifts. They do not bring justice to the fatherless, and the widow’s cause does not come to them….”

Isaiah 1:4–23 ESV

(In Isaiah’s day, Israelites, but in Lorenzetti’s day Christian people who would not accept the Shepherd’s direction.)

The objective announced in this room was indeed justice but as fidelity, participation in the restoration announced by God through Isaiah and then brought by Christ.

I will restore your judges as at the first, and your counselors as at the beginning. Afterward you shall be called the city of righteousness, the faithful city.”

Isaiah 1:4–26 ESV

The great question for any Christian people (inherited by their governors) was whether the people would be God’s hand in the Kingdom that Christ had announced (in politics as elsewhere). The Nine, through the mouthpiece of Lorenzetti’s imagery, said that Christianity itself meant politics, a specific politics with defined objectives, principles, and effects. Religion, for the Nine, “overshadowed by the political”? What I understand Viroli to mean by “republican religion” was that religion requires a politics that understands the nature of societal trouble. Notice that the imagery on these walls is devoted to articulating that understanding instead of arguing the special merits of republicanism. Through this imagery the Nine stated that if it is insufficiently political, in the terms set out on these walls, then ‘Christian religion’ is not Christianity.

3 | Modernism’s ‘But this is completely impractical’

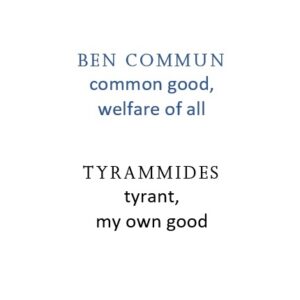

There is one small section of the north wall that we left unexamined: the end of the circuit that began with divine Wisdom, passed from the heavens down to Justice and the citizens, across the bench that Common Good shares with the virtues, and then back up to the ceiling, ending in the Theological virtues of Faith, Hope, and Charity. Without this component the outlook that is summed up in the words of Peter would not be present, and if you slight in this scheme the role of the Theological virtues, a very different reading of this wall is impossible to avoid. It is a defective reading that has been encouraged by a fact pointed out by the Dutch art historian Hanneke van Asperen.

Although the fresco, especially the part with the allegory of good government, has been carefully and extensively studied, the vertical axis with its personification of Siena (the ‘good ruler’) and the theological or divine virtues (Faith, Hope, and Charity) has not received much attention. Most scholarly attention has gone to the more prominent horizontal axis of the fresco which portrays the cardinal virtues.

Hanneke van Asperen, “The Virgin and the Virtues:

Charity in Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Representation of

Good Government,” Artibus et Historiae 37:73 (2016), 55–56

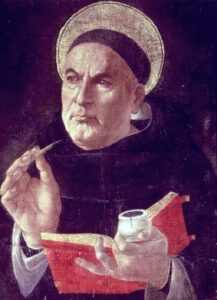

We do not have merely an over-attention to the virtues; without the import of the Theological virtues the Cardinal virtues that most scholars concentrate on will be seriously misread. How? To paraphrase Thomas Aquinas, all our efforts to be virtuous are in vain unless we enter into a life of a certain kind with God, and the motivations to do so are all given to us by God. This is the domain of what Aquinas called the Theological virtues: they are all about man’s connection with God and they are all, to quote the Apostle Peter, “granted to us” by God. Both of these facts Lorenzetti shows us.

[]

The best way to see the relevance of this is to ignore it (as is usually done) and just look at what we have before us as a political theory. The north wall, apparently, presents the solution to the tyranny that the visitor confronted as he or she entered the room. That solution is to secure the justice both called for and defined by Wisdom, an achievement that involves the virtues. What, then, is the plan? Is it Be virtuous?

People appear happy to think so. Modern historians, who have no difficulty sharing the modern dismissal of medieval politics (noted by Viroli) can agree: the medieval reliance on virtue is just more of that trouble: ‘the usual medieval excursus on virtue, but how is any of this a plan of governance?’ What answer will those critics get from modern defenders of virtue ethics? ‘This is a perfectly adequate plan of governance.’ In saying that they are misreading what they are offered in this representation of the virtues. Both of these modern readers make this mistake.

How to correct this? What has indeed been said on this central wall (and let me sum up the last instalment’s discussion) is that if, for the sake of justice – for the love of justice (“Love justice you who are rulers on earth” – Wisdom 1:1) – the rulers of Siena do succeed in cultivating the virtues:

- do exercise prudence (if, by attending to past, present, and future, they do learn what to do, prudence being a kind of knowledge); and

- do display temperance (though “everyone loves a bribe and runs after gifts”, if the rulers overcome such desires by seeking a better gift); and

- do persevere in this way of dealing with the people, despite the hardship this brings them – if, that is, they have fortitude and actually do “correct oppression” (confronting the power-rich oppressors instead of turning a blind eye to them, for the sake of their own comfort); and if they

- do show the magnanimity that engages the above-named behaviour for the benefit of the least members of the society (“the fatherless” child, “the widow”, “the foreigner”, and “the eunuch” – Isaiah 56:3)

– what is said, on this wall, is that if these conditions are satisfied then tyranny will be averted. But were we not bid to be wise? Let us do our best, then, and not fail to draw on the wisdom that we have, which tells us that all of that is phenomenally unlikely. Yes, if we could resist the causes of tyranny then that “city of righteousness” can be ours to inhabit, but how do the rulers of Siena do this?

Modern political types (followers of Hobbes and Machiavelli) right away dismiss this moral plan as naive (we will not find such people), and just as quickly modern proponents of virtue deny this (such people can be found). In these responses to Siena’s plan, however, both have mistaken what the Room of the Nine is offering as a plan: be virtuous. To flee tyranny and become a city fulfilling its promise, turn back to the virtues. This is an assumption commonly read into the idea of ‘virtue ethics’ itself, which is taken to deliver a basic message: to avoid human misery (tyranny, emptiness, unhappiness) have virtue, become virtuous.

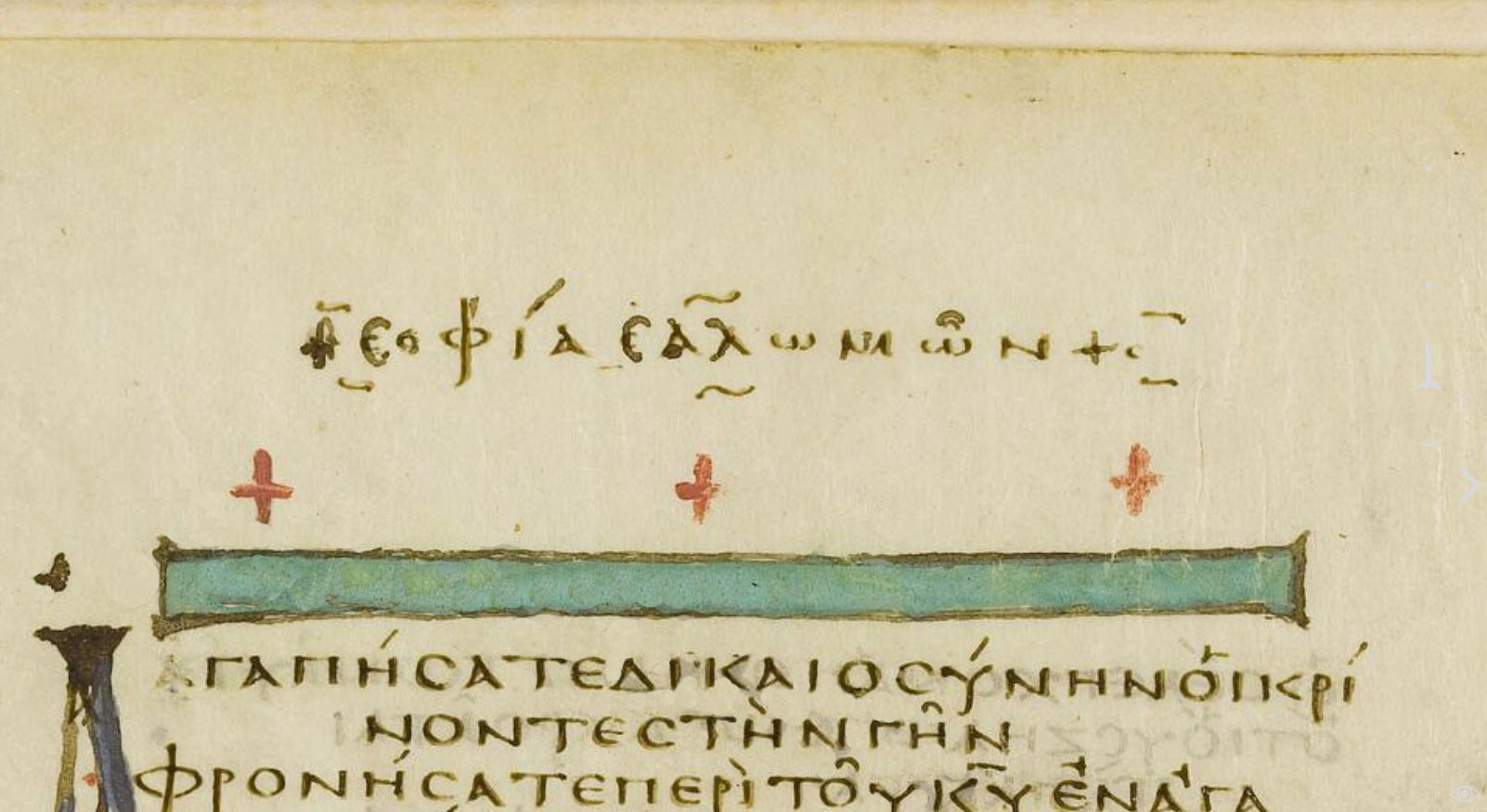

But that reading of ancient and especially Biblical accounts of virtue, brought to a scheme of imagery that, as we have seen, takes explicit direction from the Book of Wisdom – a Jewish work that is, however, not part of the Hebrew Bible – is burned to cinders by this very text.

O … Lord of mercy, who hast … ordained man through thy wisdom, that he should have dominion over the creatures which thou hast made, … and execute judgement with an upright heart: Give me wisdom,…. For I thy servant and son of thine handmaid am a feeble person, and of a short time, and too young for the understanding of judgement.… Thou hast chosen me to be a king of thy people, and a judge of thy sons and daughters:…. And wisdom was with thee: which … knew what was acceptable in thy sight,…. O send her out of thy holy heavens, …

– notice that that is where the north wall’s imagery begins: with a winged image of Wisdom sent out of the heavens to the Sienese –

that being present she may labour with me, that I may know what is pleasing unto thee.… For what man is he that can know the counsel of God? or who can think what the will of the Lord is? For the thoughts of mortal men are miserable, and our devices are but uncertain. For the corruptible body presseth down the soul, and the earthy tabernacle weigheth down the mind that museth upon many things…. And thy counsel who hath known, except thou give wisdom, and send thy Holy Spirit from above?

Wisdom 9:1–17, in The Apocrypha, KJV

(Iowa Falls: World Bible Publishers, n.d.)

This being our nature we can have no plan – a plan being a thing matched to our powers – to be virtuous. We cannot “execute judgement with an upright heart” (knowing what is needed, knowing what to do to discover it) because we are “feeble” in just this sector of our being. To “know what is pleasing” to God in the many situations we find ourselves in is beyond us: only if divine wisdom is sent down to ‘work with us’ could we find our way. We cannot by our own powers work ourselves into divine insight. Only if God “gives” his own wisdom to us could we govern with actual justice.

So shall my works be acceptable [that is, provided that Wisdom is sent down to me], and then shall I judge thy people righteously, and be worthy to sit in my father’s seat.”

Wisdom 9:12

However, because modern Christians are modern in their rejection of this very image of man-in-need-of-God (found here in the Book of Wisdom, an Apocryphal book, but essentially the same view was voiced by Peter) it will not suffice to state this and move on. The deficiency that makes it impossible for us to be virtuous – this fact of our nature – is very much worth making crystal clear, if I am able.

MISUNDERSTANDING A CHRISTIAN ETHICS OF VIRTUE

It is the reader’s business to decide what to make of the message of the Room of the Nine; I am in no position to tell people what to believe about politics. What I can, perhaps, control is a distortion of that message. Reject the message if you wish, but do not reduce what the Sienese put on their walls to any modern position. That I can perhaps help prevent by making the medieval and the modern pictures clear in their difference.

Contemporary Christians who are advocates of virtue ethics will often acknowledge the message of deficiency in Wisdom chapter 9, but then assign it to a phase of life that is virtually ended once the “Holy Spirit” called for at 9:17 is received. Once the Christian is made righteous (or has righteousness ‘imputed’ to him) by this, his or her weakness is dispelled: the born-again Christian possesses wisdom: knows God’s will, becomes virtuous, judges the people “righteously” exactly as the author of the text (writing as Solomon) appears to say we can do. But the text makes a stipulation: this is possible given what?

So shall my works be acceptable, and then shall I judge thy people righteously, and be worthy to sit in my father’s seat.”

Wisdom 9:12

The answer is, given our relation with Wisdom. Drop that element and the result is altogether different.

Everything depends on Wisdom (which is an image of divinity) “being present” with the Christian so that “she may labour with me” (9:10). To labour with me means to exercise me like a hard master – in the original Greek (the language in which the Book of Wisdom was written) this verb has the meaning of heavy toiling (thanks to John Tingley for this clarification). What is present you pay present attention to (while being reborn is past and done). The presence of Wisdom is contact with perfection, and the signal of that contact is the unsurpassable glory of God:

For she [Wisdom] is more beautiful than the sun, and above all the order of stars: being compared with the light,….”

Wisdom 7:29

Contact with glory never leaves a person convinced that he possesses this glory (in his wisdom, his virtue). Only a person who has forgotten the glory of God and is attending to his own image succumbs to this, in fact, defensiveness with respect to his own powers – and such people are not the people who are reasonably considered

worthy to sit in [the] father’s seat.”

Wisdom 9:12

The idea of the glorious Wisdom of God, “more beautiful than the sun,” coming down to ‘work with us’ – a glimpse of this is offered in the image of Spes in the upper right corner of the wall) – pictures something very different from possession of divine wisdom; it is possession of relation to divine wisdom. You are given here an image of a ‘connection with the divine that makes forgetfulness of the standard impossible’: LORD show your beauty constantly, that I may be guided always by the standard of beauty, the light of the sun itself not the dim reflection.

The Room of the Nine is itself, in fact, an attempt in art, architecture, and poetry to restore this connection, to bring the perfection of the divine virtues before the people who need it, and Lorenzetti has not entirely failed in that endeavour. He is, however, not Simone Martini or Giotto and his faces are often just workmanlike representations that do the basic job (the rather grim face of Wisdom comes in for special mention). But it is no easy matter to paint what is “more beautiful than the sun”.

In painting the virtues superhuman in stature Lorenzetti does enough to tell us that these are ideals, … bigger than us. That the Common Good, seated on the bench in their midst and even larger than they, is the ideal of man participating in the divine nature in ruling – is a divine achievement and not one of us – this is really quite clear. Wisdom, says the book named here, “is the breath of the power of God … flowing from the glory of the Almighty” (Wisdom 7:25): this is a bench within God. All the virtues flow from the Almighty.

The faithful Christian who knows what the virtues are – perfections, glorious qualities of God all demonstrated by Christ – does not believe that, in being given Wisdom, he possesses her.

[]

We return then to the question prompted by any suggestion that the Room of the Nine recommends a plan of virtue. Can the citizen just become virtuous? How is that done with the thoughts that he has?

For the thoughts of mortal men are miserable,….”

Wisdom 9:14

What chance is there that a member of the Nine, who held his position for only two months (so that

in any given year as many as fifty-four citizens sat on the Nine),”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 17

would heed this ‘call to virtue’ and do all of the things in the list given above?

Lorenzetti’s image, I agree, states that those are the actions that are needed to attain the objective. It should also be noted that in the Book of Wisdom itself the exact virtues set out in the fresco are itemized in a verse that says they are taught by Wisdom.

And if a man love righteousness, her labours are virtues: for she teacheth temperance and prudence, justice and fortitude:….”

Wisdom 8:7

But no one ‘has got virtue’, as it is not a content that passes over the heaven and earth divide, transmitted by Wisdom. It is contact with Wisdom that teaches it, and teaching does not mean an activity taking you to the point where you ‘have got it’; it is the presence of Wisdom that teaches it. Virtue in human beings is the sign of a presence in the life of a person who witnesses the beauty of Wisdom, that has the effect of overwhelming and stifling the pull of evil.

Again, a person cannot pick up a book on virtue or take a course in it and learn virtue. Ask yourself how an ordinary person or a baptized person becomes an exemplar of, say, prudence, given what the lore about prudence involves (what we are reminded of by the figure on the wall with three lamp-lights). He could certainly read the Summa and learn that he must have perspicuity (possess this special power of mind), but learning this fact does not give it to him. Aquinas teaches that he must also have a knowledge of fundamentals (all the relevant ones) … as well as an inclination to attend to circumstances … and thus an ability to suss out the details of circumstance pertinent to a just decision – all of this, simply to be prudent. Aquinas teaches what must be acquired (which is not just information but a disposition as yet unpossessed), but how is actual virtue taught?

It is not clear, even, how a person can become more prudent, given what prudence is. It is no doubt possible to improve these powers by resolutely applying oneself to specifics that you can appreciate you have neglected (for instance, you can give yourself a prompting to engage more with knowledge of the past, what Aquinas calls recollection), but, first, resolutions to improve are events in time, not easily transformed into sustained attention. They are quite readily crowded out by new events – the Book of Wisdom mentions

the earthy tabernacle [that] weigheth down the mind that museth upon many things….”

Wisdom 9:1–17

These are the distractions generated by a world of unceasing events. The troubles and lures that explain our lack of virtue do not step aside once we have decided to tackle virtue.

But even if we carry out the plan to ‘think about the past’ we miss the mark, since such a plan is far too crude: the point is not that; it is knowing what, in the past, it is relevant to think about (and how does an imprudent person fall on that insight simply by desiring to be prudent?).

And, finally, the message in the Room of the Nine is that justice is the fruit of prudence, not more prudence. Let us suppose that halting efforts to be more prudent do advance us in prudence; the achievement of more prudence is still not prudence. The result of that will surely be, somewhat more virtue – but the effect of that will be, somewhat more justice. Is that what this room is about? Are the Nine announcing the triumph of somewhat more justice – when we turn to the final mural, will that be what it shows us: a somewhat better world?

There is no need to look at all four virtues; the same pattern repeats with all of the rest. How is a regular citizen to be magnanimous when magnanimity is a desire (that others, all others, have the goods that you yourself crave)? How do you ‘enact’ or ‘practice’ a desire? (Actions and desires are two distinct things.) If magnanimity is to realize itself, it will involve, in addition to desire, a lively attention to the implications of our decisions for other people. Well, it is only people of a certain character who have those inclinations. It is not possible to ‘do the thing that has character’ (do the magnanimous thing) because it takes magnanimous thinking to hit on that particular thing. And so on for the other virtues.

THE APOSTASY OF ‘CAN-DO VIRTUE’

If you are in agreement feel free to skip ahead to the next section, unless you are among the people who believe that the trouble with our age is that we do not advocate virtue. The Room of the Nine is not a resource useful in that lesson, unless its message is replaced with the new practical philosophy.

Calling people to virtue does not generate virtue. We can improve ourselves (on those occasions when we are making the effort), but what is thereby produced is not virtue. It is either virtue that matters or what is less than virtue (whatever improvement it is in our power to make). If this is the New Virtue, the improvement that is practically possible, if this is modern virtue, then we no longer have an ethics of virtue at all, only its perversion. A ‘virtue ethics’ of that description breeds vice: satisfaction with injustice.

The vision of Christian virtue, Christian ethics/politics, is not a vision of the humanly possible – of improvement; it is a vision of the divinely beautiful, of the ideal. Only a perfect man is magnanimous. To take a step in the direction of Christlikeness marks an improvement and an improvement is good, but it is not magnificent. Modern man drops the magnificent to speak up for the improvement because he is an effective apostate, which is the right appellation for a Christian who believes only in the power of man.

Such a person fails to see what the medieval picture of the virtues is. Lacking a Christian outlook, he or she understands ‘ideals’ as mere targets to fall short of, all our misses being virtue, because they are improvements over not trying. That is simply a picture of virtue with God removed.

The ‘can-do’ mindset of modern people makes it almost impossible to understand what a Christian ‘ethics of virtue’ is teaching: it is less an improvement plan than a reflection of God. The Christian vision of virtue holds up a picture of ideal behaviour that it acknowledges is found in virtually no one – to which a thoroughly modern person cannot help but respond, Then what is the point. Machiavelli rejected medieval political reflections as useless, complaining about the very tendency to

The ‘can-do’ mindset of modern people makes it almost impossible to understand what a Christian ‘ethics of virtue’ is teaching: it is less an improvement plan than a reflection of God. The Christian vision of virtue holds up a picture of ideal behaviour that it acknowledges is found in virtually no one – to which a thoroughly modern person cannot help but respond, Then what is the point. Machiavelli rejected medieval political reflections as useless, complaining about the very tendency to

picture republics and principalities which in fact have never been known or seen,”

a preoccupation he saw as an abandonment of the purpose of politics. When

how one lives is so far distant from how one ought to live,”

how could we expect the actual good results that good leaders aim to give their people to flow from that ‘ought’? The ideal is always the not actual; it is the practical that matters. Because the kind of political theory we need is

a thing which shall be useful … [the good theorist must] put on one side imaginary things …, and discuss those which are real.”

Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince (1515), trans. W.K. Marriott, ch. 15

But, in the modern fashion, Machiavelli has missed the point of medieval political writing. It was not a how-to; it was the statement of an inexorable truth about the thing most central to its subject: the reward that we are aiming at (liberty, freedom from tyranny, justice for all) is inflexibly bound to conditions (of character) that are not to be found in us. Put in other terms, the city we most deeply desire is a city that people like us cannot have – period.

The practically minded Machiavelli replied, Then the dream city does not matter; we must stop dreaming and claim the good that lies within our power. The apostate Christian whom I mentioned just a moment ago is a modern person because he or she thinks in exactly this way.

The faithful people of God say no such thing – nor have they cause for despair, because of the promise of God recorded in their Scriptures (Wisdom, 2 Peter, etc.).

They do not see the Room of the Nine as a Machiavellian does, as the outlay of a futile or exaggerated plan. It has an altogether different message, which is that the city that human beings long for, a ‘peaceable kingdom’ (Romans 14:17), is not an achievement of man at all; it is a work of God that we can participate in, engaging with the Wisdom of God, or not. We can certainly give up that dream to have what we can get by our own power, but that is to repeat the failed formula that produces the results depicted on the wall of tyranny.

Machiavelli would have called the central wall an exceedingly bad plan, but it is not a plan: it is a reminder of the nature of the political project. That reminder or lesson can be coerced by the mind fixated on power into coughing up a plan (How to get the virtue on which what we want depends), but the ‘procedure’ it has tortured out of the lesson will lack the defining quality of plans and procedures: it will not say Here is what you do. The message will be that there is nothing to do but reflect on the actual nature of the world that we have mistaken as our stage for securing the good; it is a world in which another event is already unfolding but that we are ignoring: an event of being (of which the good, the political project, are part). Virtue belongs to participation in that event.

Machiavelli would have called the central wall an exceedingly bad plan, but it is not a plan: it is a reminder of the nature of the political project. That reminder or lesson can be coerced by the mind fixated on power into coughing up a plan (How to get the virtue on which what we want depends), but the ‘procedure’ it has tortured out of the lesson will lack the defining quality of plans and procedures: it will not say Here is what you do. The message will be that there is nothing to do but reflect on the actual nature of the world that we have mistaken as our stage for securing the good; it is a world in which another event is already unfolding but that we are ignoring: an event of being (of which the good, the political project, are part). Virtue belongs to participation in that event.

The reason that, as I noted earlier, the figure of Common Good looks to the virtues is not that they show him how to realize his dream; they secure in him the knowledge of what his dream requires, which is the perfection of men – and then this at-first disturbing message (which illuminates his predicament) continues to unfold, like a beautiful blossom, blooming as it is in the precincts of Wisdom (“For she is the brightness of the everlasting light” – Wisdom 7:26). In the eyes of its intended recipient (a member of the Nine, or a citizen who elects a member, or who might next year be chosen as one), what the scheme of the

north wall reveals is a project that is fully beyond this man’s powers (exposing by its light the fact that he is far from being prudent, magnanimous, temperate, steadfast), but the illumination continues. As the light of Wisdom illuminates the condition of Siena, it exposes the damage that is always done to the city by setting it in human hands (in the care of “feeble persons”), the damage done by tying its fate to the human capacities that both the Machiavellian and the apostate modernist are fixated on, and at this moment Wisdom reveals governance to be a divine work – a work using and somehow, in a divine way, perfecting, human powers, the powers of those who “labour with” Wisdom, the radiance of God present in their midst. Being

north wall reveals is a project that is fully beyond this man’s powers (exposing by its light the fact that he is far from being prudent, magnanimous, temperate, steadfast), but the illumination continues. As the light of Wisdom illuminates the condition of Siena, it exposes the damage that is always done to the city by setting it in human hands (in the care of “feeble persons”), the damage done by tying its fate to the human capacities that both the Machiavellian and the apostate modernist are fixated on, and at this moment Wisdom reveals governance to be a divine work – a work using and somehow, in a divine way, perfecting, human powers, the powers of those who “labour with” Wisdom, the radiance of God present in their midst. Being

the breath of the power of God … she can do all things: … she maketh all things new: and in all ages entering into holy souls, she maketh them friends of God,…. For God loveth none but him that dwelleth with wisdom.”

Book of Wisdom 7:25,27–28

The event already unfolding is a divine work, and we are typically obstructing it. We could become part of it only by way of friendship with God, and friendship is not a project. Any friendship that is begun with a plan to ‘become a friend’ is born of an objective that some quality seen in the other person would feed (there is some knowledge of the other person at its root) – but this is not actual friendship. Friendship must not only begin with the friend but be for the friend, as we shall see in what the authors of this wall set as its crown and conclusion.

The figure of the Common Good, then, surrounded as he is by the virtues, is indeed, much as Quentin Skinner claimed,

a depiction of the type of signore … that a city needs to elect if the dictates of justice are to be followed and the common good secured,”

Quentin Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes:

Two Old Questions, Two New Answers,” Journal of the

Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 62 (1999), 10

but what type of man is that? It is the type who understands the full project, the entire wall that surrounds him, especially the portion that surrounds his head, his highest part. This is a person who possesses no wisdom but binds himself to the presence of Wisdom. We have seen (discussing Martini’s Maestà) that Wisdom is also Christ; the New Testament identifies Jesus as the

wisdom of God”

1 Corinthians 1:24

– the figure of Wisdom in the corner of, the start of, the central wall is a ‘type’ or representation of Christ. The common good could indeed be “secured” (not necessarily at this moment but in time) only by “friends of God”, who are not people who ‘like’ God and live by their own instincts but people who “dwell with” Him and who, keenly attentive to the beauty of God and the standard this sets, are enabled to participate with God.

There is a ‘counsel of despair’ here only for a faithless person, a person without the Gospel, the good news announced by Christ. When the Kingdom was coming Jesus healed the lame, the blind, and the deficient. For the blind man to regain his sight, it was necessary for that man, confessing his incapacity, to ask for healing, to ask Jesus to remove his deficiency – which is to say (how can you remove an absence?) to give him the ability he lacked. All of the virtues depicted on this wall are perfections of Christ, offered in the same way.

[]

To know that the longed-for condition of a just city is beyond our capacity, because it is a work of people who are not like we are, but at the same time that it is offered by God (who is answering a human longing placed in the heart by God), is the most crucial piece of political knowledge.

The Machiavellian has shut it out by deciding that man alone is the generator of political goods. But if, as Machiavellians hold, what political theory is really about is what man can achieve by his de facto powers, then political theory is never concerned with progress toward unstinting justice and peace. It substitutes instead material benefits that raise the GNP but by destroying the livelihoods of people in flyover country; it wins justice for the oppressed but by depriving the guiltless of freedoms essential to a republic of liberty; it secures the freedom to pursue genuine goods that you choose for yourself but by taking the life of an equal who is as loved by God as you are – and so on, through all the vices depicted on the wall that opens Lorenzetti’s cycle. Nothing stops the Machiavellian from promising everything (lies in fact help him to obtain the coveted actual results), but the Machiavellian will never deliver good without destroying good, because perfect good requires a transformation that the Machiavellian – even the apostate Christian modernist – has dismissed as fantasy. The transformation of everyday people into God-like beings is a pipe-dream, but what makes it so is simply the Machiavellian’s vestigial conception of God, a God much weaker than him.

How is this signalled in the Room of the Nine? I have indicated some of the connections between the scheme I have just described and the image but to justify this as the proper way to read the fresco I must say more. As I have suggested, we have a decisive fork of interpretation in the presence of the Theological virtues: if the ‘can-do’ conception of virtue can accommodate the Theological virtues, it remains viable, but the Theological virtues are offered to man by God precisely because man is blind (he cannot see what virtue entails), lame (he will not walk as virtue requires), and deaf (he cannot be told what I have just said – he insists that he can do it all by the very power God has given him).

4 | The Theological Virtues

Why should we not read the imagery in this room as propaganda for the Nine, a message to Siena that her government is a selection  of nine of the best and the good: the kind of man rippling with virtue, analogues of the Christian he-man that we are propagandized with today by a certain fringe of political Christians? (Notice the difference between two kinds of image: depictions of ideal qualities, like virtue, concord, etc. – these being divine qualities – and depictions of ideal people, effective political agents.)

of nine of the best and the good: the kind of man rippling with virtue, analogues of the Christian he-man that we are propagandized with today by a certain fringe of political Christians? (Notice the difference between two kinds of image: depictions of ideal qualities, like virtue, concord, etc. – these being divine qualities – and depictions of ideal people, effective political agents.)

In Siena we are not seeing propaganda for perfect people because of the superior place, in this scheme, of both the Book of Wisdom (where the scheme begins) and the Theological Virtues (with which it ends). No one touched by either wisdom or the Book of Wisdom could bring himself to say, without laughing, To have a just state, be virtuous, or, Our Republic is run by the virtuous.

Two themes of the text of the Book of Wisdom are matched to the imagery in this room:

- in the first part of the text readers are called to love and to exercise justice and wisdom

(again, the substance of the first two sections of the north wall);

- a central part of the text teaches that wisdom proceeds only from God;

(these are the chapters that we have just been discussing, echoed in the Room of the Nine in the divine character of the virtues that hover, larger than life, above the human citizens of the city). This idea of a

power that proceeds from God alone is one of the chief qualities of the set of Theological virtues, which are depicted above the head of Ben Comun, at the end of the circuit that runs through the imagery here; it is with the Theological virtues that the thread we have been following ends.

power that proceeds from God alone is one of the chief qualities of the set of Theological virtues, which are depicted above the head of Ben Comun, at the end of the circuit that runs through the imagery here; it is with the Theological virtues that the thread we have been following ends.

Chiara Frugoni noted that

the theme of the Book of Wisdom is the same as that of our fresco,”

Chiara Frugoni, “The Book of Wisdom and Lorenzetti’s Fresco

in the Palazzo Pubblico at Siena,” Journal of the

Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 43 (1980), 240

but that book has many themes, and among them we have seen the claim that we cannot learn how to judge rightly, how to become “worthy” to occupy the throne of judgement (which is God’s “seat”),

except thou [God] give wisdom.”

Wisdom 9:12,17

That is a defining quality of all three of the Theological virtues. Feldges-Henning notes this quality, remarking that

the ‘influence of divine grace’ is indicated by the three theological virtues, hovering above the head of Ben Comun.”

Feldges-Henning, “The Pictorial Programme

of the Sala Della Pace,”160

Starn and Partridge observe that

Both the Treasure [by Brunetto Latini] and the frescoes assign the highest place to the contemplative or theological virtues of Faith, Charity, and Hope, and then distinguish these from the subordinate moral virtues.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 42

The latter are counted subordinate because they are actually beyond us. The Theological virtues, on the other hand, are given to us, and they are also the effective virtues. As Thomas Aquinas explains in the Summa,

because of them [– through them –] God makes us virtuous, and directs us to Himself.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, trans. Fathers of

the English Dominican Province, Great Books of the Western World,

vol. 20 (Chicago: Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 1952), II-I, question 62,1

The second defining quality has just been stated here: the Theological virtues are all given by God to “direct [people] to Himself”.

Beyond the human happiness attainable by and proportionate to man’s nature, there lies another attainable only by God’s power and by sharing God’s nature. To achieve this…, we need God to give us the kind of start towards it, that our nature gives us towards human happiness. This start we call the theological or deiform virtues, directed to God, instilled by God, and revealed by God in the Scriptures.”

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae: A Concise Translation,

ed. & trans. Timothy McDermott (Notre-Dame:

Christian Classics, 1989), 240 (from II–I, 62, 1)

In his explanation of the Theological or “deiform” virtues Aquinas notes that the perfection of virtue, the bearing of Christian fruit, comes in no other way but by the perfection of the relation to God. He refers to another book of the Apocrypha, where we read,

My son, if thy mind is to enter the Lord’s service, wait there in his presence, with honesty of purpose and with awe, and prepare thyself to be put to the test.”

Sirach 2:1

This we have encountered in the Book of Wisdom: in the very “presence” of the glory of God, personified in that book as Wisdom we will be exercised by God; the “light” will shine on what we are faced with in life (on the matter of judging, deciding); “awed” by actually divine perfections we will not be seduced into satisfaction with our own decisions. This very presence, light, and awe does nothing so much as to draw us into that relation.

MORAL PLUS THEOLOGICAL VIRTUES

The art historian George Rowley called all the virtue figures we have looked at stand-ins for us:

the earthly Civic Virtues through whom government exercises its power are represented as human beings assisting the Commune.

George Rowley, Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Princeton, N.J.:

Princeton University Press, 1958), 99–100

That is, he is contrasting wingless figures who sit on an earthbound bench with winged figures who hover in the heavens. What is the meaning of this contrast? The best answer to this brings with it a perfect summation of what I have said above about virtue: the presence of the Theological virtues (acknowledged by the scholars but not factored in) makes it fully clear what the north wall’s schema is all about. The contrast is explained by Aquinas, neatly treated here by Etienne Gilson. Everything essential comes clear if we just read his account.

That is, he is contrasting wingless figures who sit on an earthbound bench with winged figures who hover in the heavens. What is the meaning of this contrast? The best answer to this brings with it a perfect summation of what I have said above about virtue: the presence of the Theological virtues (acknowledged by the scholars but not factored in) makes it fully clear what the north wall’s schema is all about. The contrast is explained by Aquinas, neatly treated here by Etienne Gilson. Everything essential comes clear if we just read his account.

All virtues are defined in relation to the good toward which they are directed. The end of natural moral virtues is the welfare of the city or state which is the highest human good because it embraces and rules all the others. It concerns, indeed, the terrestrial city…: Athens, Rome, or the place we happen to be living in….”

This “human good” is the good as found within human life, people living with each other; every society (Greek, Chinese, etc.) knows it. And here is why Christian virtue ethics is distinct from the Greek understanding of virtue that it drew from.

The Incarnation, which is at the very center of Christianity, has completely transformed man’s condition. By making human nature divine in the person of Christ, God has made us sharers in the divine nature: consortes divinae naturae (II Peter 2, 4).”

In his account of virtue Aquinas makes reference to this passage of Peter.

Here we have a profound mystery. The Incarnation is the miracle of miracles, the absolute miracle, the norm and measure of all others. For the Christian at least, it is the source of a new life, the pledge of a new society, a society founded on friendship between man and God, and among all those who love one another in God. This friendship is charity itself.”

Charity is caritas, meaning love; the greatest love is this totalizing love of God for man, seed of the love of man for God, which tends toward the state of the heavenly city built of “love [for] one another in God”. Gilson recalls “the terrestrial city”, which “has its own virtues” (prudence, magnanimity, etc.) – that is why the virtues we have discussed are seated beside the personification of a city. But

the natural man is quite unable to transcend his own nature. The germs of the virtues necessary to do this are not in him. They come to him from without, infused into him by God like gifts or graces, for no man can be expected to acquire by himself something he is by nature incapable of acquiring.

There is therefore a … distinction to be made among virtues: … between theological and moral virtues…. Theological virtues … are neither acquired nor acquirable by the practice of what is good. As we have said, the good of which it is a question here cannot be naturally practised by man. How then can he form a habit of doing something of which he is quite incapable?

Étienne Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas,

trans. Laurence K. Shook (Notre-Dame, Indiana:

University of Notre-Dame Press, 1956), 337–38

This is the often denied fact that eliminates any suggestion that the message in the Room of the Nine is To govern well, turn back to virtue, be virtuous.

But the practical mentality is not stopped by this; the wheels of such a mind just see this as fuel for another practical question: If I myself lack the power then from where can I get it? (Notice what the objective here is: the power – to govern justly, fulfil the dreams of citizens, rescue Western civilization.) When the answer comes back that it is God who bestows it he will then turn directly to God, but though there is ‘turning to God’ in this scenario this has nothing to do with what we are seeing at at the top and centre of Lorenzetti’s schema – the Theological virtues – and the second quality that defines them, explains Aquinas, completely excludes this kind of attention to God. Whatever this inclination is it is not such a virtue.

Gilson writes,

The theological virtues are distinguished from … moral virtues in that the former have God for their immediate object….”

Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 338

God as a means to earthly peace or justice is an orientation to high but mundane ends. The theological virtues draw man to God, so as to have God (to dwell in the divine presence, experiencing awe, entranced by beauty – all that we have seen in the Book of Wisdom).

Quite simply, if other ends than God prevail in one’s consciousness then it is not God one has turned to (this whole conception of ‘turning to God’ is actually a deception, and it is chiefly the person engaged in it who is deceived). Any person believing he has turned to God, to receive the power to effect an earthly project, and whose attention is held by that project, has succeeded in turning to what he sees as the means to a good. That is not God. To turn successfully to God, the source and essence of all good, is to encounter what “is more beautiful than the sun”. It is a that beauty that one has seen in the earthly ends that inspire you, reflected there, but to turn and find God is to encounter the beating heart of your project, but much more. Thus, writes Aquinas, these virtues

are called ‘theological virtues’: first, because their object is God, inasmuch as they direct us aright to God: secondly, because they are infused in us by God alone: thirdly, because these virtues are not made known to us, save by Divine revelation, contained in Holy Writ.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II-I, question 62,1

We have indeed had them revealed to us by the Book of Wisdom, and they are revealed again here by the Room of the Nine, yet that revelation does not always penetrate.

Gilson explains the effect of the ‘infusion’ mentioned by Aquinas.

The theological virtues allow [a person] to act with God and in God. By faith we believe God and in God. By hope we entrust ourselves to God and hope in Him because He is the very substance of our faith and hope. By charity the act of human love attains to God Himself. We cherish Him as a friend whom we love and by Whom we are loved, and Who through friendship is transported into us and we into Him.

Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 338

Here he has listed the three Theological virtues: Faith, Hope, and Charity.

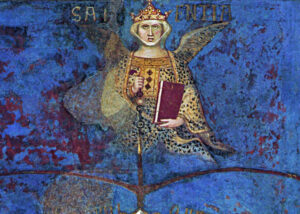

THE IMAGE

How are these virtues depicted?

The wings of the theological virtues and their position above the head of Siena make the theological triad a heavenly counterpart for the ‘benched’ virtues below. Because of their elevated status Lorenzetti gave the theological virtues wings whereas the others are without.”

Van Asperen, “The Virgin and the Virtues,” 58

But the issue is why the elevated virtues are elevated. By contrast with the moral virtues (which Aquinas called “connatural”, i.e., linked with our nature and natural objectives) the Theological Virtues, writes Rowley,

are depicted as celestial creatures with cherubim bodies, for the ultimate authority of government must reside in the spiritual realm.”

Rowley, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, 104

They are indeed celestial, but this cannot be their point as it misses the character of Theological virtues. Earthly rulers (even tyrannical ones) exercise an authority that is granted them by God; this they were reminded of in the Book of Wisdom itself:

Hear…, O ye kings, and understand;…. Give ear, ye that rule the people,…. For power is given you of the Lord,….”

Wisdom 6:1–3

The relevance of the Theological virtues to what Lorenzetti is presenting is not the authority or power that descends from God to the earthly project. The directionality has to run the other way, upward. It is rather that

ye that be judges of the ends of the earth”

Wisdom 6:1

are given the ability (should these judges receive it) to dwell with God and rule in Him – a condition that would transform their rule profoundly. Another healing miracle would be performed. In the union with God that becomes possible through attention to God, the divine virtues most directly relevant to rule (on the bench beside Ben Comun) may be acquired by human rulers. Rowley indeed notes a divine dependency,

for the origin of wisdom is not human reason but divine reason in which Justice and Concord have their source,”

Rowley, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, 99–100

but he does not say how or even whether that gap between human and divine may be closed. This is the very domain of the Theological virtues.

CHARITY

We will understand this group better if we just start at the top, with the greatest of all virtues;

So now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love.”

1 Corinthians 13:13 ESV

The historians point out the following:

Returning to Lorenzetti’s painting, we notice that caritas is the highest of all virtues, and although it is a theological virtue, it has … strong erotic meaning. Lorenzetti paints caritas red, love’s color,…. In her right hand she holds an arrow, pointed downward – one of the most typical symbols of love piercing someone’s heart. She carries a burning heart in her left hand, to suggest that charity is ‘amor concupiscentiae’, a real erotic passion.”

Viroli, As If God Existed, 25–26

Another notes

Charity’s upturned gaze.”

Van Asperen, “The Virgin and the Virtues,” 67

What in these remarks appears strange, even off course and out of step with everything we have looked at – and this strangeness is in the image – is to be explained, I think, by reference to another book of the wisdom literature: the Song of Songs and

the Christian interpretative tradition that [viewed] the Song of Songs as a description of the soul’s embrace of God under the figure of a wedding song….

F.B.A. Asiedu, “The Song of Songs and the Ascent of the Soul:

Ambrose, Augustine, and the Language of Mysticism,”

Vigiliae Christianae 55:3 (2001), 299

The highest image on this wall, the culminating image, though it is small, puts everything we see below it into another key, the key of a wedding song, a song of love that anticipates a union.

Viroli notes that

Charity is veiled, to be more seductive.

Viroli, As If God Existed, 26

This sounds misjudged but is not; he is pointing out that it is a transparent veil, which is revealing. We tend to forget that the trope of the veil has that meaning – I, at least, have always fastened instead on the implication of covering, but veils are filmy. Wherever hiddenness is discussed in terms of something veiled the message is surely that the veil indeed covers but does not truly conceal. If a person looks carefully (or with the right kind of attention) what lies beneath can be seen; what is veiled is never fully concealed. Veiling is related to revelation.

This sounds misjudged but is not; he is pointing out that it is a transparent veil, which is revealing. We tend to forget that the trope of the veil has that meaning – I, at least, have always fastened instead on the implication of covering, but veils are filmy. Wherever hiddenness is discussed in terms of something veiled the message is surely that the veil indeed covers but does not truly conceal. If a person looks carefully (or with the right kind of attention) what lies beneath can be seen; what is veiled is never fully concealed. Veiling is related to revelation.

I suggest that what is implied here, by the representation of Caritas, is that What is veiled and not seen by all is being revealed to you – and the word so relevant to the Theological virtues is ‘given’ – the inner secret (the body in this image) is given to you, as the receiving beloved. And what is the thing given? The whole conception of politics as we ordinarily think of it conceals the truth within it, what it is all really about – the meaning of politics is regularly concealed, but it is given here and now. The whole of politics (that is, seen as what it is, not obscured by our misconceptions) is in fact the reciprocated love of man and God.

Viroli is entirely right to notice the jarring shift to the erotic, which obviously involves nothing physical; the physical element of the image simply sounds the central note of the Song of Songs (which Jesus’ talk of a wedding links with). Politics is tyranny until it is part of the divine-human union, the marriage of heaven and earth.

The face of Caritas differs from the treatment of the Theological virtues beside her in that she looks directly at the viewer. Those using the Room of the Nine would be men and the gender dynamic here is not accidental. This always strikes me as an unfortunate impediment to extending the message of what is represented here to women, today, and yet, at the same time, I do not think that we have in the Song of Songs, and here, anything like a man-centered dynamic, quite obviously. Women have an imaginative agility, a capacity to respond to the following lines in a way that men cannot, occupying the female role but also shifting, in the fitting way, to understand what is said through this imagery.

My sister, my bride, you ravished my heart;

You have ravished my heart with one look from your eyes,….

Song of Solomon, 4:9 SAAS

(The lines that follow extol the beauty of the bride’s breasts.)

By way of these gifts it is love that is given (the image of the heart). The recipient, the one who is looked at, is loved by Caritas, being caritas, and like all the virtues here she is a figuration of God. And when the love that is given through the gift is understood to be given, it pierces the beloved (the arrow), who loves back. The ancient meaning of the arrow of Cupid is that: it causes reciprocated passion. (“Passion”, writes Aquinas, “is the effect of the agent on the patient.”) But the cause here is not an implement or a trick, a spell; it is that God gives his heart, his essence. One scholar locates all these elements in Augustine:

In Confessions 9.3.3 Augustine writes of the arrow of God’s love in suggestive images that could well come out of the Song of Songs (4.9f.)….

“You pierced my heart with the arrow of your love and we carried your words transfixing my innermost being. The examples given by your servants whom you had transformed from black to shining white and from death to life, crowded in upon my thoughts. They burnt away and destroyed my heavy sluggishness, preventing me from being dragged down to low things. They set me on fire with such force that every breath of opposition from any deceitful tongue had the power not to dampen my zeal but to inflame it more.”

Asiedu, “The Song of Songs and the Ascent of the Soul,” 302

It is clear, in these words of Augustine, that this is the fire of purification (as in the fires that chasten gold). They are the flames mentioned by Christ that, Paul explains, burn away all bad works:

It is clear, in these words of Augustine, that this is the fire of purification (as in the fires that chasten gold). They are the flames mentioned by Christ that, Paul explains, burn away all bad works:

each one’s work will become manifest, … because it will be revealed by fire, and the fire will test what sort of work each one has done.

1 Corinthians 3:13 ESV

In the Kingdom of God the flames of love purify, and the flaming heart held out by Caritas is an image of the ‘teaching’, noted earlier, conducted by Wisdom – by way of the “presence” of God (Wisdom 7:10). Love burns away the chaff. Contact with God ‘prevents us from being dragged down to low things’ in the sphere of governance.

Consider an example. It is easy for a person to take note of Charity here and then count it a ‘political virtue’, and then say, Because I love you I want the best for you, and the best is for you to do as you should. This ruler then enacts ‘charitable’ laws that oblige the citizen to do what it is good for him or her to do. But this just shows the resistance to Christian ethics – it is a misunderstanding of the message in this image that the moral theologian Servais Pinckaers calls typically modern. “Friendship”, he writes, is one of the

important themes in ancient moral thought [that] have disappeared from modern ethics precisely because of the latter’s emphasis on the concept of obligation.… According to [Aristotle] the whole point of law and the political life, over and above justice, was to provide for friendship among citizens…. The theme of friendship was prominent among the Greek Fathers,…. It reached its climax in St. Thomas, who defined charity as friendship with God and who described the work of the Holy Spirit in the world as a work of friendship (Summa contra gentiles 1.21–22).”

Servais Pinckaers, Sources of Christian Ethics

(Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1995), 19

(Latini too places “friendship … under charity”.)

Caritas – friendship, love – has an entirely different mode of well-wishing than obligation (making you do what is best for you, or just compelling you to see that what you are doing is wrong, to see what it is you ought to do). That supposed ‘Charity’ is not Caritas at all, and what is essential is to move toward actual friendship and love – indeed, to make it the supreme principle that it is in the Room of the Nine. What this means, however, cannot even be imagined by uncharitable people. It is fathomable not by ‘thinking about the love God has’, or by reading what you are reading now, etc., but by having discovered that love. That event (the arrow or dart) will cause one to want to remain in that condition, and it is a purgative, transformative condition.

In that ‘way of living’, says the Book of Wisdom, we are gradually being reformed to participate in divine Caritas.

I have mentioned love, its cause and effects. That is the structure of Aquinas’ treatment of love in the Summa (I–II, questions 26–28); when he discusses Caritas the Theological virtue he cites Jesus (John 15:15):

‘I will not now call you servants … but my friends.’ Now this was said to them by reason of nothing else than charity. Therefore charity is friendship…. Not every love has the character of friendship, but that love which is together with benevolence.”

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II–II, question 23, 1

On two key points Aquinas cites Augustine:

‘By charity I mean the movement of the soul towards the enjoyment of God for His own sake’.”

Augustine, De Doctr. Christ. 3, 10; cited by Aquinas,

Summa Theologiae, II–II, question 23, 2

Writes Pinckaers, this is

love of an object for its own sake,….

Pinckaers, Sources of Christian Ethics, 28

And

Charity is a virtue which, when our affections are perfectly ordered, unites us to God, for by it we love Him.”

Augustine, De Moribus Eccl. 11; cited by Aquinas,

Summa Theologiae, II–II, question 23, 3

It is a Theological virtue in that it

is the Holy Ghost Himself dwelling in the mind.”

Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II–II, question 23, 2

Finally, it is supreme in its power, and it renders all the other virtues true.

No virtue has such a strong inclination to its act as charity has, nor does any virtue perform its act with so great pleasure.”

Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II–II, question 23, 3

No strictly true virtue is possible without charity.”

Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II–II, question 23, 7

This last point makes the relevance of everything shown on this wall clear. Think of a drawing of a city, drawn in perspective; now imagine seeing all the lines filled in and completed, every line running to the vanishing point. Virtue is put in perspective by Charity, as follows.

Aquinas writes that we can speak of all the virtues

as being ordered to some particular end;”

the end of temperance is to rightly restrain desire – but in this, he says, “there is no charity.” That is, when naming the “particular good” of temperance nothing is said about the highest objective, which cannot be captured in talk of governed desires, or of achieved justice, or the good of perseverance, etc. (What are is a particular good? An example he gives elsewhere is,

… some particular good, as to build dwellings, plant vineyards, and the like;….”

These are goods of human life, and they extend to the civic goods of justice, temperance, etc.)

What are all these goods for, if anything? If there is a fuller end, the picture is left incomplete by how we think of them; if there is a final and greater purpose, they lack a connection with it. For that reason, says Aquinas, the good of temperance

is not a true, but an apparent good,”

and, in being ordered to a good that is left hanging in this way, temperance itself

is not a true virtue…, but a counterfeit virtue.”

Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II–II, question 23, 7;

example from I–II, question 109, 2

A remarkable claim in an ethics of virtue! That is, the political virtues are not realized as what they truly are when they are rooted to the earth alone, to the goods of human society. In the earthly city they attain their particular ends, but until they have lines drawn through them straight to the final end, they are missing not just the full picture but the full substance of virtue.

It is only when virtuous acts are acts of Caritas – acts done with love for God, and done with the love that God has for man, the way a person in love imitates the other – that they become real vehicles of the union of man and God.

FAITH

Faith (FIDES) … is shown in profile, supporting a large cross;….”

Norman, Siena, Florence, and Padua, 148

Van Asperen notes the link between Lorenzetti’s scheme and the Tresor written by Dante’s teacher Brunetto Latini, writing that

because of their sublime qualities Latini gives primacy to the theological virtues,”

Van Asperen, “The Virgin and the Virtues,” 58

but these virtues are present here for much still more concrete reasons. A person might ask, On what is this whole scheme of politics based; what does it have to recommend it? The discussion of the Theological virtue of Faith answers this. Based upon the sources that appear to underwrite the fresco (Scripture, Latini, Aquinas, et al.) that answer would be that here we are not dealing with things that can be known. In politics, fully understood, we are not talking about

things seen either by the senses or by the intellect [the intuitive grasp of self-evident principles]…. All science [scientia – the meaning is ‘knowledge’] is derived from self-evident and therefore ‘seen’ principles,”

Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II–II, question 1, 4–5

but in this domain we are concerned with things that must be either believed or not believed; they are not given to us in the manner in which we know things: they are not “manifest” to us. Aquinas cites Gregory the Great:

‘When a thing is manifest, it is the object, not of faith, but of perception’.

Gregory, Homily XXVI in Evang.; cited by Aquinas,

Summa Theologiae, II–II, question 1, 5

Suppose that you are not a believer; you do not believe in a “Spirit of truth” that is sent to you to move you where seeing does not. Nevertheless, if there is such a spirit, you can be so moved and believe. Aquinas explains that

the Holy Ghost … is the Spirit of truth: for such was Our Lord’s promise to His disciples (John 16:13): ‘When He, the Spirit of truth, is come, He will teach you all truth’,”