Ideal government II | Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Vision of Government

In this essay,

• PAINTINGS AS POLITICAL THEORY? – ANSWERING THREE BASIC QUESTIONS OF GOVERNMENT:

1 | WHAT IS THE OBJECTIVE OF GOOD GOVERNMENT?

2 | IS SUCH AN IDEAL REALIZABLE?

3 | WHAT, IN PRACTICE, MARKS OUT PROPER ACTS OF GOVERNMENT?

• THE WALL OF DESOLATION – WITH REMARKS ON THE MISUNDERSTANDING OF TYRANNY

• THE COURT OF DISCORD

• THE COURT OF CONCORD

• THE WALL OF GLORY – OR, MAKING SIENA GREAT AGAIN: JOY IN THE GLORY OF THE FLOURISHING CITY

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | Politics in painting

How can art be political, and even ‘contribute’ to a debate in political theory? The historian Quentin Skinner writes that in the 13th and 14th centuries the Italian city-republics produced

a distinctive political literature concerned with the ideals and methods of republican self-government. Several of the most eminent philosophers of the age took part in the argument, including St. Thomas Aquinas…. But it was an artist, Ambrogio Lorenzetti of Siena, who made the most memorable contribution to the debate. This took the form of the celebrated cycle of frescoes he painted between 1337 and 1340 in the Sala dei Nove of the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena.”

Quentin Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher,”

Proceedings of the British Academy 72 (1986), 1

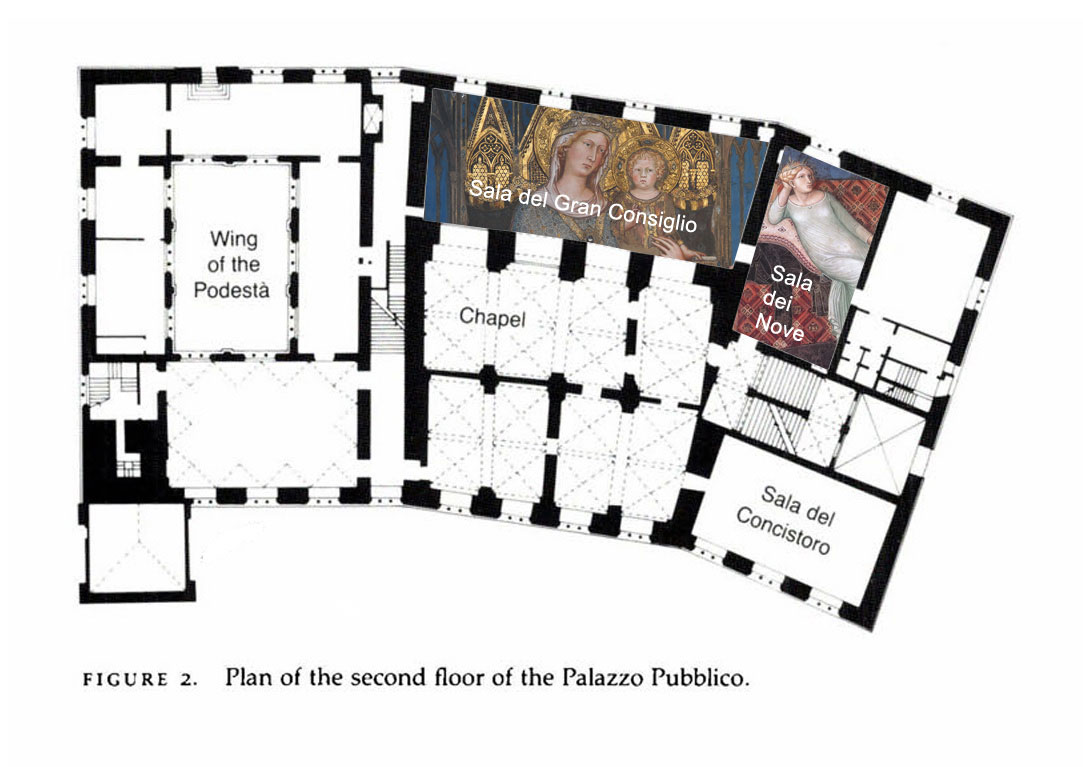

How is this possible? How could three walls of images, a set of murals in the room adjoining the council chamber we looked at last month (examining Simone Martini’s Maestà), make a contribution to political thought?

How do three walls of images accomplish this? In an article he titled “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher,” Skinner writes,

How do three walls of images accomplish this? In an article he titled “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher,” Skinner writes,

Although it is obvious that these paintings do not constitute a text of political theory in the conventional sense, it is equally obvious even to the casual observer that they are basically intended to convey a series of political messages.”

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: Political Philosopher,” 1

Skinner’s study was devoted to unfolding “the meaning and interpretation of those messages”, messages we can examine here with accompanying details of the paintings.

I have not mentioned the usual ‘title’ given to this work, which I am ignoring as irrelevant – in fact Skinner suggests it is even wrong:

The frescoes are generally known as the Buon governo or ‘allegory of good government’. But I have preferred to avoid these descriptions. The suggested title is definitely not original, and strictly speaking the paintings are not allegories.”

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: Political Philosopher,” 1

Others have referred to them as

the Peace and War murals”

Joseph Polzer, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s ‘War and Peace’ Murals Revisited:

Contributions to the Meaning of the ‘Good Government Allegory’,”

Artibus et Historiae 23:45 (2002), 67

but it puts the cart before the horse to begin with any title. Whatever a title ought to be (why do we need one at all when the artist did without one?) will hinge on a proper understanding of the images and – important here – the texts written out on the walls to accompany them.

THE ‘SALA DEI NOVE’ OR ROOM OF THE NINE

This is a work begun some twenty years after the fresco by Simone Martini that I discussed last month here. It is from that room that

official delegations, petitioners, and guests would have entered [the Room of the Nine], as visitors still do[, having first] paused to admire Simone Martini’s fresco of the Virgin enthroned with her entourage of saints.

Randolph Starn & Loren Partridge, Arts of Power: Three Halls of State in Italy,

1300–1600 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 18

Imagery was chosen also for the walls of this smaller room, where the Nine operated on their own (joining the other parts of government, mentioned last month, in the larger room for general assemblies). This imagery was directly linked with what we saw in Martini’s Maestà, a painting concerned with the foundation of government – that is, with what the task of governing was seen to be part of: life itself, worship and fulfilment in the body of Christ.

But with that established, what particulars of government (especially one that is a republic) remain to be unfolded? We might imagine that there are two key issues.

TWO QUESTIONS

As we have seen, the republic was to operate as an organ, so to speak, in the body of Christ, but what does that entail? What would be the sign of this, what measure would be used to establish that it was doing so?

We could perhaps rephrase this by asking, What is the objective of a good and indeed divinely marked government? We might call this the primary practical question: what specifically are the governors trying to do?

Today, I suspect, people will answer pragmatically, even if Christians: obviously, they say, our objectives must be reduced to what is humanly possible. But that, we saw, was a position rejected in Siena: to govern within the scope of what is humanly possible – to abandon as impracticable the ideals of good government – was to turn your back on the God who had blessed you: the God you had called on in an hour of need, with annihilation threatening (Siena surrounded by a much superior army).

In Siena the answer to the primary practical question was given in the Book of Wisdom:

Love justice you who are rulers on earth.”

Wisdom of Solomon 1:1

The objective of government is justice pure and simple, that conception of justice that was a Biblical inheritance – what Alasdair MacIntyre termed “justice as such” (as opposed to the sort of justice ‘your people’ were satisfied was justice, the status quo of justice there and then. – If you think about republicanism, in fact, the ‘republican ideal’ itself could be understood as a plan to push beyond such contingent framings of justice).

What is enjoined in the Torah is, not a justice restricted to Israel, but justice as such, not only a law in much of its detail specific to Israel but also a law holding for all peoples.”

Alasdair MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality?

(Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1988), 150

If that is the objective – here is a secondary question – from where would the governors of Siena obtain the power to realize such an ambition?

We saw in our look at Martini’s Maestà that that was another question answered by the same verse of the Wisdom of Solomon. The answer was, by actually loving Wisdom, which is not a thing but a who, identified in the Christian tradition as Christ. That is, if one loved Wisdom – loving Wisdom in the way a mother loves her child – then the power of Wisdom would be granted.

It is easy to misunderstand this, misunderstanding the verb, to love, but that error is correctible if we simply adhere to what the central image of the Maestà gives us, to keep us on track. It is one thing to say you love … (whatever it is you claim to love), but a mother is truly devoted to the object of her adoration, her own child – and that is what the Maestà set out as a political foundation. If the governors of Siena loved Wisdom in such a way as to be devoted to it, attentive to it, ever conscious of it, attracted to its particular beauty, then Wisdom and everything that is part of it, including Justice, was opened to it, for having in this way joined oneself to God (as a mother is joined to her child). For having become part of the body, the whole. The power to be just, in the ruler’s actions, would be granted: only the love of justice (the love of God) is empowering.

(At this point, I suspect, some may be thinking that God is known for his mercy not his justice, but I am reading the call to justice in the opening line of the Book of Wisdom as a call, to man, to adopt a standard issued to human beings not gods. And, further, doesn’t mercy call us to know justice; mustn’t the merciful judge know exactly what justice demands in order to set that aside and show mercy? To undercut Wisdom 1:1 with the ‘mercy of God’ is to get beyond ourselves – perfection as the enemy of the good.)

To the extent that the love was true (and motivating of the very kind of action that was due) just government would be achieved. Translate this outcome into present-day language and we see what this would mean. Just government is precisely government that does not rob a person of any freedom rightly his, does not deny a person what she has a right to. Medieval and Renaissance Italians did not speak of rights (and certainly not individual rights); their idea of freedom was ‘freedom of the community’, a translation of vivere libero. Skinner explains that though talk of

the unconstrained enjoyment of … specific civil rights … is not to be found in … any of the … writers on ‘vivere libero’ [nevertheless] the enjoyment of individual freedom [was] one of the profits or benefits to be derived from living under a well-ordered government.

Quentin Skinner, Liberty Before Liberalism (Cambridge University Press, 1998), 18

People governed justly are give what they are due.

ONE MORE IMPORTANT QUESTION

Here it is clear what remains to be clarified. What is this appropriate action?; that is, how do we identify it, so as to pick as governors those actions that are just?

If the first questions of government are the higher ones – What is our true purpose in governing (Siena’s answer was given in the Maestà), and then, What is the practical objective (also answered in the Maestà) and What makes that attainable, the next question is, What are the actions that distinguish a justice government, or, perhaps, what are the standards that single these out? In this way we arrive at the frescoes in the Room of the Nine.

But Skinner tells us that here Lorenzetti makes a kind of argument – a point that prompts not just the question what argument but, more deeply, how does a painting argue in any way at all? His answer to the deeper question is that if we “read Lorenzetti’s cycle as a narrative” we will find that it “articulates an argument.”

Having been invited by the Nine to celebrate the values of a republic, Lorenzetti opens his narrative by highlighting an argument usually accorded marginal significance by the predominantly monarchical political theory of his age…. As in the case of a literary narrative, Lorenzetti’s pictorial argument asks to be read from left to right. So far as I know, this approach has not been systematically followed, but it serves to uncover a number of interconnections between the different parts of Lorenzetti’s cycle.”

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes,” 1, 3

How does this unfold? Before I consider Skinner’s reading allow me to quote, as a preface, the suggestion of the historian Chiara Frugoni, noting a detail that links the entire fresco with what I have discussed above, recalling Martini’s Maestà. In a central place on one wall we see, written out,

the legend Diligite iustitiam qui iudicatis terrain (Wisdom 1:1 [Love justice you who are rulers on earth]), … the verse which seems to me to have been meant as an indication to the medieval viewer and to us of how the entire fresco should be read; the more so since in this allegorical complex, which is intended to represent the city and its rule, the religious element is very strong.”

Chiara Frugoni, “The Book of Wisdom & Lorenzetti’s Fresco in

the Palazzo Pubblico at Siena,” Journal of the Warburg

& Courtauld Institutes 43 (1980), 239

2 | The sequence of images, I: Tyranny

Originally this room was entered through a doorway in the east wall. Historian Randolph Starn and art historian Loren Partridge note that

the scenes of desolation painted on the west, ‘bad government’, wall would thus have been a newcomer’s first view of Lorenzetti’s frescoes.”

Admittedly, there is not much to see as much of the paint on this wall has fallen away.

Admittedly, there is not much to see as much of the paint on this wall has fallen away.

A dystopia of violence, sinister personifications, and menacing texts confronts us on entering the Sala dei Nove. The physical state of the painting is eerily in keeping with the effect.”

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 18, 19

Skinner reads this wall, perhaps, as illustrating the tyranny to which monarchy is prone – at least, he points out that temptation. Noting that the 13th-century theorists of government

had generally insisted that, as Giles of Rome … declares, ‘kingship is the best form of government’, they usually admitted the danger that kingship may degenerate into tyranny,”

Skinner remarks that on this wall we see some

of the appalling consequences that ensue when this exact form of political degeneration takes place…. We see … the rule of tyranny and its ruinous effects on city and countryside,”

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes,” 1, 2

the left section of the wall (the paint mostly lost) illustrating the contada or countryside, next to it the walled city (the councillors of the Palazzo Pubblico had responsibility for a circle of land extending from Siena thirty km in radius). But in his political writing Skinner notes the difference between

the left section of the wall (the paint mostly lost) illustrating the contada or countryside, next to it the walled city (the councillors of the Palazzo Pubblico had responsibility for a circle of land extending from Siena thirty km in radius). But in his political writing Skinner notes the difference between

republicans in the strict sense of repudiating the institution of monarchy”

Skinner, Liberty Before Liberalism, 22 n. 67

and what he calls

a politics of virtue … (Worden … argues … that ‘it is as a politics of virtue that republicanism most clearly defines itself’).”

Skinner, Liberty Before Liberalism, 23 & n. 68, citing historian Blair Worden

There is no sign here that the tyranny we are presented with here is the tyranny of a king.

Yet most people link tyranny with tyrants, single abusive rulers, especially tyrant kings and dictators. I invite you to pause and consider your own understanding of the notion of tyranny; do you not define it in exactly that way, as the behaviour of a tyrant pictured as a single person? That is not what we are seeing in this room. Advocates of republics indeed reject monarchy, but what kind of republican, committed above all to the idea of a free state –

free states … [being] defined by their capacity for self-government”

Skinner, Liberty Before Liberalism, 26

– is immune to tyranny? The republicans of medieval Siena did not make our mistake, which is to think that tyranny is a form of government. They understood that

where the sovereign is a king, the tyrant (if there is one) will be the king,

and mutatis mutandis:

where the sovereign is the people, the tyrant (if there is one) will be the people.

In Siena, which is republican, it is the people who will be the tyrant unless tyranny can be avoided. And that was exactly our further question: How avoid it? What is the standard that marks an action as just, so that we can see what is just and choose it?

The imagery on this wall depicted republican Siena’s real danger, which was not monarchy, which they had rejected: they needed no picture of monarchy gone awry! – Think of the foolishness of painting up a wall showing the tyranny of a king, produced as a tribute to republican virtue. Yet I have a sad fear that people will not grasp this point. How many people are in fact quite ready to believe that Republican virtue (US-style-2024) consists in not being a Democrat? No, facts are not virtues: no one is a hero by choosing a party!

What Trump voter is at risk of suddenly warming to Democrat projects (which that person must be reminded, by murals, to reject)? Again, no. The American republican is at risk of failing to follow the republican star, which is a star on the opposite horizon from the leftist’s. The danger he or she faces is to pass as a republican, committed to self-government and a free state, and not actually be one, because the actions this person endorses routinely strip people of their rightful freedom, as Lorenzetti has illustrated in the mayhem spread across this wall (for details, read on).

The danger is always to be blind to what you are doing, to choose the wrong thing and not see this: to strip freedom away when you think you are protecting it – and you take a great stride toward that when you detach the notion of tyranny from governing (a task that every person has) and treat it as a form of government (Tyranny! a thing that you, in choosing republicanism, have ‘so wisely’ rejected!). But if you look upon that as wisdom you are misconceiving wisdom (it is what you need now), and, further, that is not what tyranny is. The Sienese of 1340 saw these things far more clearly than we do.

In the misery depicted in the lands on this wall (town and country) we see the actions of the people, not of any single figure or leader. In the Room of the Nine the first objective for the Sienese was to signal the danger that governors, even republican governors, were ever at risk of succumbing to, and it was the danger of injustice that I have already underlined. The Sienese understood that you get tyranny not when you fail to choose a republican form of government but when you are unjust. You get tyranny when you fail to realize the republic you have attempted to create, a ‘polity’ or manner of government in which all the people participate and justice reigns. You set up a Republic (accomplished in Siena even before the Palazzo Pubblico was begun) and structured your government accordingly – but justice was not done and now you have Tyranny. This is what Lorenzetti depicts on the room’s west wall.

‘THE GOOD OF THE SELF’

Describing this wall, historian of architecture Richard Ingersoll writes,

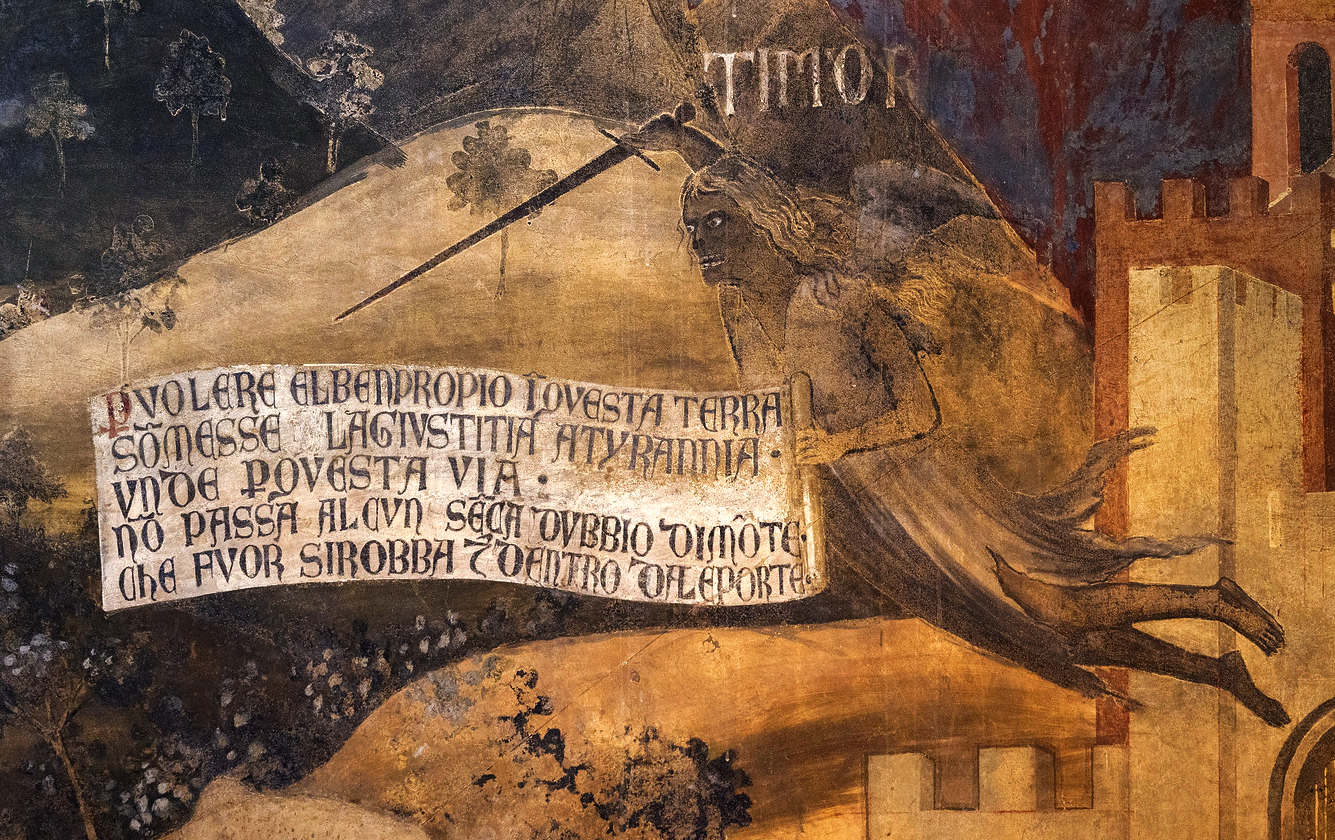

Flying above the city gate is a ragged harpy figure labeled ‘Timor’, or Fear, who brandishes a sword and carries a sign reading

‘Because each seeks only his own good in this city,

Justice is subjected to Tyranny;

wherefore along this road nobody passes without fearing for his life,

since there are robberies outside and inside the city gates.’Below her we see the countryside ablaze with burning buildings and looting, abandoned fields, bridges blocked by soldiers.”

To look more closely, I cannot do better than put you in the hands of Starn and Partridge, who give a masterful introduction to these paintings.

Amidst the ruins of the picture, we can barely make out a swelling landscape, populated here and there with ghostly armies and surmounted by a harpy figure labeled Timor (Fear) with an extended scroll. Farther to the right, a walled city with gaping windows and doors and dilapidated buildings opens onto spaces where such figures as we can see enact little scenes charged with violence – soldiers exiting the gate, a woman being throttled by one garishly costumed figure and robbed by another, a man assaulting a woman, armed figures grasping a female figure dressed in red, a prostrate body bleeding from a chest wound.

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 19

Why is justice not attained here? The great first lesson of the Room of the Nine explains why. There is no lesson in the fact of evil presented here; the great question is cause of this symphonic perpetration of injustice, injustices of every kind spread throughout the population. The evil-looking figure hovering over it is not the cause but, as is explained in the scroll it clutches in its clawed hand, the fruit delivered by one causal principle, stated in the opening words of the most prominent text on this wall:

Why is justice not attained here? The great first lesson of the Room of the Nine explains why. There is no lesson in the fact of evil presented here; the great question is cause of this symphonic perpetration of injustice, injustices of every kind spread throughout the population. The evil-looking figure hovering over it is not the cause but, as is explained in the scroll it clutches in its clawed hand, the fruit delivered by one causal principle, stated in the opening words of the most prominent text on this wall:

P(ER) VOLERE ELBENPROPIO | Because each seeks only his own good,”

or ‘the good’ (elben) of the ‘self’ (propio), condensed to a magic formula of evil: ELBENPROPIO.

Starn and Partridge recall Dante, who had died in the decade before this painting was begun.

Starn and Partridge recall Dante, who had died in the decade before this painting was begun.

Like the pilgrim’s journey in the Divine Comedy, then, the itinerary of Lorenzetti’s painting begins with una città dolente – a suffering city.

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 19

As a part of the sequence of images conducting that narrative argument mentioned by Skinner, these scenes are meant to show us the state of things before the arrival of the republic. What does a king who “seeks only his own good” care about these crimes in his kingdom? Only when they impinged on that good would he even notice them. But if tyranny is what we have said – the name of every form of government in which justice is not done (as the Sienese explain, not done “because each seeks only his own good”) – could the Nine succumb to the same temptation? Most certainly, and then this panorama of misery would also be scenes from the future of Siena, not just scenes predating the republic.

THE COURT OF DISCORD

Further to the right on this wall we shift from a representation of actual town and country to the conceptual, presented here with a court of personifications.

A series of figures is seated, facing us, on a raised platform, in the way judges are seated in a court. We think of ‘going to court’ as legal language, as indeed it is, but it derives from political rule: Solomon was both judge and king; politics is adjudication (judging what is to be done). At the centre of this group one figure sits on his own throne (the others share a bench) raised up on his own platform.

A series of figures is seated, facing us, on a raised platform, in the way judges are seated in a court. We think of ‘going to court’ as legal language, as indeed it is, but it derives from political rule: Solomon was both judge and king; politics is adjudication (judging what is to be done). At the centre of this group one figure sits on his own throne (the others share a bench) raised up on his own platform.

Twice the size of all the others he is

Twice the size of all the others he is

a diabolical cross-eyed figure, with horns and fangs, marked in silver lettering TYRAMMIDES [Tyrant]. Although he is enthroned in the style of a king, he wields not a sceptre but a dagger in his right hand. His foot rests on a goat, symbol of luxuria,

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes,” 2

one of the Seven Deadly Sins. Which sin this refers to depends on the context, as the word has several possible meanings;

the Latin luxuria may be translated as ‘indulgence’, ‘excess’, ‘dissipation’, or even ‘lust’.

Shawn R. Tucker, ed., The Virtues & Vices in the Arts:

A Sourcebook (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2015), 6

There is really no question that here it indicates the exact thing given such prominence by the figure of Fear, which had explained its own appearance, saying

Because each seeks only his own good.”

The tyrant indulges in the luxury of ‘the good of the self’; Luxuria here is Self-indulgence.

We have to understand this as part of the definition offered here of tyranny. The north Italian jurist Bartolo da Sassoferrato, a contemporary of Lorenzetti, gave two definitions of tyranny in his treatise on this subject. There is the technical sense of a usurper of power, but Bartolo’s attention was focused on the second.

We have to understand this as part of the definition offered here of tyranny. The north Italian jurist Bartolo da Sassoferrato, a contemporary of Lorenzetti, gave two definitions of tyranny in his treatise on this subject. There is the technical sense of a usurper of power, but Bartolo’s attention was focused on the second.

A tyrant, in the strict sense, is one who rules a whole commonwealth unlawfully. But it should be understood that every person practices tyranny in his own manner. For sometimes one practices tyranny in a commonwealth through the power of an office he has accepted; another in a province, another in a city, another in his own house, while another practices tyranny in his own thoughts through his concealed wickedness.

Bartolus of Sassoferrato, De tyranno 2.53–62, referring to

Gregory the Great’s Moralia, 12.38;

cited by Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 22–23

What does he mean? Bartolo is saying that when we decide an issue simply by seeking our own good, ignoring the question of the good of the community, injustice is done. Indeed, it is done even in our own thoughts (but how: there is no community there). The answer is clear. A person ‘seeking only his own good’ expels from his mind even the question of the good of others; it is not a consideration. He is an absolute tyrant going through the world without concern for the impact of his seeking-of-good (the dagger in his right hand is the benefit he holds out to the world). This is what the tyrant luxuriates in: his own good.

In this same passage Bartolo makes equally clear the inescapability of politics, the foolishness of the person who says ‘I have no desire to govern others’. That simply means that you have no desire to notice how you are ruling over others, because you cannot escape making judgements in which the welfare of others is the prime consideration. The fool who says ‘I’ll happily stick to my own business’ is a fool because the thing he is sticking to does not even exist. He is, as Aristotle noted, a social animal, a member of society whose actions affect others and whose ‘inactions’ constitute self-indulgence. Ambrogio Lorenzetti paints such a person as … – and what does the face of the tyrant tell us? He paints him as ugly, insane, evil, and vicious.

This ruler is vicious. For us the primary meaning of this word is “savage or ferocious” (Webster’s Universal College Dictionary); then one day we learn about vices and realize that it also means “characterized by vice”, but we may never connect these meanings. They are fully connected in the Room of the Nine, because in a country in which self-indulgence reigns there is obliviousness to the commonwealth, the ‘commune’ in Siena, the society as a whole; that obliviousness is what the formula of each-person-seeking-his-own-good means. Forgetfulness of the commonwealth culminates in savagery.

That is what we were shown in the image of the land: a land in which the people are forgotten. Forgotten people are unprotected from the worst elements of society. Rapes and murders are on the rise; I have read that crops are burning in the background here (but I have not found an image in which to see this): Lorenzetti has painted the headlines from an ungoverned land. Starving people become desperate to survive; in a badly governed land, dangerous self-concern only spreads and the effect of this is savagery.

The sword of bat-winged Timor (you are likely familiar with the word timorous or fearful) is unsheathed here, and no leader looks out for your welfare. So the ferocity that is one meaning of ‘vicious’ is an effect of the injustice that is the second meaning, Justice being the virtue of acting rightly in society, acting with due consciousness of the impact of your acts on others, acting in such a way as to render to others what others are due. The more those in the seat of power fail in this, the more fearful life in this society will be – and at every level, because Lorenzetti’s conception of tyranny is political. It concerns man insofar as he/she makes judgements of social significance.

The sword of bat-winged Timor (you are likely familiar with the word timorous or fearful) is unsheathed here, and no leader looks out for your welfare. So the ferocity that is one meaning of ‘vicious’ is an effect of the injustice that is the second meaning, Justice being the virtue of acting rightly in society, acting with due consciousness of the impact of your acts on others, acting in such a way as to render to others what others are due. The more those in the seat of power fail in this, the more fearful life in this society will be – and at every level, because Lorenzetti’s conception of tyranny is political. It concerns man insofar as he/she makes judgements of social significance.

Indeed, that disturbed society will be rife with certain prevailing conditions. Note the other figures sharing the dais with the Tyrant.

On a platform against a crenellated wall of the desolate city presides a court of vices identified by their attributes and labels. Cruelty, Treason, and Fraud appear to the right of the enthroned figure of Tyranny, with Furor, Division, and War on its left.

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 19

The profoundly disturbing image of the first figure, marked CRVDELITAS – a woman holding a struggling infant by the neck, as she raises in the other hand a no-doubt venomous serpent, recalls the evil woman in the Judgement of Solomon (1 Kings 3:16–28), wishing death upon an infant. This helps to raise the key question to be asked of all six figures. Skinner interprets them as

The profoundly disturbing image of the first figure, marked CRVDELITAS – a woman holding a struggling infant by the neck, as she raises in the other hand a no-doubt venomous serpent, recalls the evil woman in the Judgement of Solomon (1 Kings 3:16–28), wishing death upon an infant. This helps to raise the key question to be asked of all six figures. Skinner interprets them as

the elements of force and fraud that keep tyrannical governments in power.

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes,” 3

I doubt that reading. I do see the way that cruelty (as in the horrific modes of execution once meted out to condemned traitors) might dissuade people from treason (action against a ruler) but this is a very specific cruelty, and the cruel wish of the bereaved mother in 1 Kings 3 did nothing to keep any ruler in power. – Hasn’t Lorenzetti already explained to us the cause of human cruelty in general?

When Solomon commanded that the fought-over infant be shared equally (“Divide the living child in two”) the woman who agreed (saying “divide him”) chose cruelty because the scope of her thinking was narrowed to herself. Only her loss mattered, overshadowing and indeed wiping away any good of ‘society’ (the life of the child – to be wasted; the second mother’s life with her own offspring – destroyed). Other people’s goods never entered her mind. This woman stands as a perfect illustration not simply of injustice but of the cause of injustice that was announced at the centre of this very wall:

P(ER) VOLERE ELBENPROPIO | Because each seeks only his own good, … Justice is subjected to Tyranny;….”

The story of the Wisdom of Solomon (to which we are directed by this personification of Cruelty) affords a perfect illustration of the defining mechanism of tyranny itself.

It is impossible to look at this disturbing image and not think of infancy in the present day, infants being a class of people whose welfare depends entirely upon the consideration of other people. Replace the deadly snake/sword-of-Solomon with the instruments used to dismember a fetus in a fetal abortion: for the good of the self the cruelty of dismemberment in the womb is both dreamed-up and overlooked.

In the pursuit of our-own-good we have not just an apology for cruelty but a magic wand that erases it. It still remains, labelled Crudelitas, but the power of ELBENPROPIO erases the ability to see cruelty (people just see health care). Cruelty becomes invisible.

In what I have said about this one figure, announcing an anti-civilizing effect of self-attention, we should appreciate that we are being given a lesson of political wisdom, as chapter 3 of I Kings tells us. There Solomon prays,

Give your servant … an understanding mind to govern your people, that I may discern between good and evil, for who is able to govern this your great people?”

1 Kings 3:9 ESV

What I have just described is the power of self-regard to remove that ability to discern, and it extends through the conditions personified by the five other figures.

Seated beside Cruelty is PRODITIO,

portrayed as a man nursing in his lap a hybrid animal – a sheep with a scorpion’s tail; [next is] Fraud (FRAUS), portrayed as a bearded figure with bat’s wings and a claw foot;….

Diana Norman, Siena, Florence, & Padua: Art, Society, & Religion 1280–1400

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 152

PRODITIO or Betrayal faces you like a lamb while concealing its true and deadly intent. So great a wrong as betrayal and treason is always done by ignoring what is rightly due the person betrayed, for some good we judge greater. In treason it may not be our own good that drives us, but what drives us is certainly our own judgement, elevated above the universal condemnation of betrayal. FRAUS or Deception covers much the same ground but in another area. The Nine being chosen from merchant class, fraud deserves separate attention from the deception linked with treason. The specific ‘practice of tyranny’ being condemned in Fraus is the indulgence of personal interests that pushes aside the regard due others in all our actions. Merchants must not defraud their customers.

On the other side of the bench to the left of the Tyrant – his ‘sinister’ side, which shows us even darker evils – we see

On the other side of the bench to the left of the Tyrant – his ‘sinister’ side, which shows us even darker evils – we see

the outright violence of FVROR, [D]IVISIO, and GVERRA.

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes,” 3

The bestial image of FUROR, a kind of boar-headed centaur,

we are surely intended to recognize as a representation of the brutish multitude, especially as we see it armed with a stone,

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: Political Philosopher,” 33

the ready weapon of the lower class. According to Giovanni Boccaccio, a contemporary of Lorenzetti,

the centaur is the very type of ‘armed, irascible, uncontrolled men, prone to every crime, such as one sees in the clients, hirelings, and evil ministers to whom the tyrant resorts’.”

Starn & Partridge, citing Boccaccio’s Genealogie deorum gentilium, in Arts of Power, 27

The violence of crowds, today as then, has as its driving engine the single issue that the mob has decided matters, imposed on others by its unilateral judgement (another variant of the habit of self-regard). (It may not be my good that I am marching in the street for, but it is my estimation of everything involved that is lighting the cars on fire.)

Next in line is

Division (DIVISIO), portrayed as a woman with loose, dishevelled golden hair, arrayed in a parti-coloured white and black gown with the Italian words SI and NON (yes and no) emblazoned across the bodice, and in the act of wielding a huge, jagged saw,

Norman, Siena, Florence, & Padua, 152

the it? I have been looking at these figures as, together, the personification of different kinds of self-regard, that central form of indulgence that causes the injustice that is tyranny, but surely it is not unjust to disagree (yes and no) about matters of importance. Skinner explains this figure

an evident allusion to Sallust’s dire warning that DIVISIO will always serve to tear a body-politic to pieces.

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: Political Philosopher,” 33

If we take this line, there is indeed nothing wrong with disagreement, but when the questions raised begin to undermine the unity of the city, grasped through

the ancient metaphor of the body politic … [– i.e.,] ‘the body of the people’ and ‘the whole body of a commonweal’

Skinner, Liberty Before Liberalism, 24

understood as a united thing (like a human body) that enjoys health all together, then in such a case the activism that says, No: Siena/Canada/America must be x (in a way that rejects that conception of health) is divisive. Insistence on this new x can mean the destruction of the republic.

Skinner calls Division and War the good state’s

darkest enemies. [Roman] writers [had] isolated two in particular: external Guerra and internal Discordia, the latter being a product partly of factious Divisio and partly of the Furor of the masses. If we turn to the left or ‘sinister’ side of Lorenzetti’s frescoes, we encounter just these companions of tyranny and enemies of peace.

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: Political Philosopher,” 33

It is not really clear, by the way, what the figure of Divisio is sawing in two, but Starn and Partridge say it is herself, and offer a different reading of the letters on her clothing. They mention

the saw that the figure of Division labelled Siena and dressed in Sienese black and white turns on herself.

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 27

Black and white are indeed the city’s colours, and Skinner explains that

Sena [is] the Latin name for Siena.

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes,” 10

What better image could there be of dividing and destroying the body politic?

[]

To sum up, if we understand these figures as representing different conditions of self-regard, as causes of the injustice that is tyranny, we can see how on this bench we have a kind of continuum of circles, with a mother and child at one end and a soldier at the other – to paraphrase Bartolus of Sassoferrato,

for sometimes one practices tyranny in one’s own house, parent to child, and sometimes one does so in the widest way, nation to nation.

Injustice can be done in both settings and from either cause terror will arise.

Before we turn, finally, to the central and indeed main wall, the trio of figures above the Tyrant ought to be noted.

Above the central figure … are three further personifications of vice: in the centre, Pride (SUP[ER]BIA), red horned and carrying a yoke and a sword; Avarice (AVARITIA), an old woman with two purses and a flail; and Vainglory (VANAGLORIA), carrying a reed, wearing a surcoat edged with gems and scrutinizing herself in a hand-held mirror.

Norman, Siena, Florence, & Padua, 152

Around the Tyrant we do not have just a set of relevant vices; we have a structure of vice.

Superbia or Pride was the first in Gregory the Great’s list of vices,

the vice that defines the sinful striving for superiority in Dante’s Purgatorio (17.119); Vainglory … [was] an interchangeable synonym of Superbia for Gregory and later writers, including Dante, and Avarice on the left (the chief competitor of Superbia as the prime evil after the eleventh century).

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 25

I suspect that the reason these vices float in the ether like this, instead of taking a seat on the judges’ bench, is that from the bench judgements of self-interest were made, as we have just discussed; but were you to ask why they were made, that is not yet explained. Why did the grieving mother in the Judgement of Solomon make her cruel demand – what actually motivated it? The thread uniting all these modes of injustice has been one person’s own good, but in calling for the division of the child that woman stood to gain nothing. There is more to the notion of self-regard than actual private benefits.

Sometimes the motivation for Fraud, say, is just such benefits or goods (thus Avarice appears in this trio), but the cruel mother in 1 Kings 3 was driven by something else: by the elevation of her own pain above every other issue that was in play, as if everything to be decided turned on that. This kind of self-regard is Pride.

Where Vainglory or Vanity is glorying in one’s own qualities (a nice-looking nose that is especially engrossing because it is yours), Pride is a self-preoccupation without such excuse. It is simply the failure to understand that other people’s grief (etc.) is equal to yours. These are the three deeper causes of injustice, injustice being the hallmark of Tyranny.

And laid at the feet of all these figures, therefore, is ‘Justice bound’, unable to function, to act, so that justice is done.

At the feet of the central ruler figure appears Justice, now no longer … active, but bound and with her scales broken on the ground beside her. Other violent acts perpetrated against both men and women are shown in the foreground, but due to damage are barely decipherable.

Norman, Siena, Florence, & Padua, 152

It makes perfect sense, then, when Starn and Partridge ask, in view of the imagery on this wall,

Who, then, is the tyrant? The tyrant, a citizen might have admitted, is me.

Starn & Partridge, Arts of Power, 24

In a republic, which was by definition concerned with entire body politic, the people understood as a whole, tyranny in the republic is the problem and concern of all, in every circle of life. It is the condition of injustice created by self-regarding judgements. Thus it was a moral and a political problem at one and the same time.

In Siena the idea of morality as a concern of individuals putting together their own picture of reality was inconceivable. Such a conception of morality would be a guarantor of injustice, as injustice was then understood. Also inconceivable was the idea of a separation of morality (as a concern of individuals) from politics (as a collective concern). To erect any sort of ‘wall between morality and state’ would mean abandoning the understanding, manifest on this wall, of the path to glory that was open to the republic. Tyranny is injustice and injustice could be driven out. To reduce politics to economic action or to the protection of each person’s freedom to live as he sees fit (as if there is no understanding of justice, leaving each person to seek his own good in the way that makes sense to him or her) – such a project would be a direct assault upon Siena, an act of self-destroying DIVISIO on the sinister side of the bench.

3 | The sequence of images, II – the north wall: Concord

Coming soon

4 | The sequence of images, III – the east wall: Glory

Coming soon

Artist

Ambrogio Lorenzetti (active 1319–1347)

Date

1337–1340

Still in its original site in the Room of the Nine (Sala dei Novi) of the Palazzo Pubblico Comunale, Siena

Medium

Fresco

Photo credit

Steven Zucker, Smarthistory