Ideal government | Simone Martini’s Maestà

In this essay,

• JUST GIVE ME THE ART (IF THIS IS YOU JUST SKIP TO SECTION 7)

• GOVERNMENT & IDEALS – YOUR VIEW IS?

• HOW DESIGN A STATE

• WHY WE ARE BAD ON POLITICS RE MORALITY

• THE EXAMPLE OF A PARTICULAR MEDIEVAL STATE …

• … WHICH CHOSE TO BE A REPUBLIC

• POLITICAL CHRISTIAN ART: HOW CHRISTIANITY SHAPED THIS REPUBLIC

Best viewed on larger screens

1 | Why are these essays like this?

These examinations of art, I have noticed, never seem to open by looking at art. Perhaps this frustrates people and is ‘the wrong approach’. (Approach to what, I ask?) But it turns out there are plenty of fast-food outlets catering to all the ‘busy people’ who get their ‘content’ on the go.

Today’s treatment will be worse than usual, in this regard – and has made me think that I don’t begin with the work of art because the issue here is really not the work, not the work of art by itself (could that ever be anything but an illusion?). It is us, our situation, a situation – and I suppose this would be a general thesis of these essays – into which a work of art is equipped to speak, to speak into even with a divine voice. If you just ‘cut to the chase’ of what the work ‘means’ or is ‘about’, you don’t care about the plot, the situation the protagonists are in. What protagonists? So you really cannot hear the thing addressed expressly to them.

Knowledge as a commodity is another distraction; I am concerned with what it is a distraction from. There is a big industry giving people the knowledge they want. There are other issues than what we want.

2 | A disturbing question or a pointless one?

Does the government of your country exemplify any particular, and good, model of government? Is the conception of government good, I mean, not the people running it. Is that conception really the ideal one – meaning not the most perfect fantasy government (who cares about that) but the one best fit to the task (the people it has to govern, the thing it has to achieve, the obstacles to that work), and what is that form of government? – This is a simple question but one we may never have bothered asking, possibly because … who ever thinks about ideal governments? Only in a naïve age (I imagine this to be the response) … only in a naïve age is time wasted musing on things like that.

But then, if you do answer that way, where do you leave yourself? Quietly accepting the corrupt form of government that you know is running things? Just coping with this situation, which is all you can do ‘since a deformed government, far from the ideal, is as inevitable as the sunrise’? – Of people who think this way it might be sensible even to ask, Are you really unhappy with your government, unhappy with this situation that you are very certain is normal?

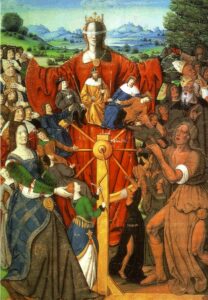

I can imagine such a person replying that it is a positive quality of the human spirit to ‘make the best of misfortune’, but I would see that mention of fortune as a dodge. (‘Fortune’ is the idea of events beyond your control: events once thought to be controlled by Fortuna, a cosmic agent acting by herself, turning the wheel of fortune. Modern people claim not to believe in such naive fantasies, but don’t they believe in forces beyond our control? In the inevitable corruptness of politics? In the defectiveness of every political system?)

We usually cloud the issue when we mention ‘fortune’, because it has always been unclear whether the ‘misfortune’ at issue has befallen us or is our own stupid doing, and if it is doing, is there really no hope of not doing it? Why is government bad: because that is the way things are, or because that is the way we make them? (Maybe, for a start, by turning our backs on the question of the right government.)

BLAME THE STOICS – BUT THAT WILL NOT WORK; OR, HOPELESSNESS IS HUBRIS

People sometimes invoke the Stoics, as wise men who tell us to ignore politics, since it is a thing we cannot control. The Stoics indeed said that the key thing was to give all our attention to what is in our control, but what they were really saying in this is that our primary business is the matter of who we are. We are to strive to be good, a man

determined always to champion what he [sees] as right.

F.H. Sandbach, “Stoics and Politics,” The Stoics,

2nd ed. (London: Duckworth, 1989), 145

What is right and how to make this right thing come about are two entirely different questions. The person who thinks the latter is his job is a megalomaniac, because it is no man’s job; it is not the job of any individual at all. That would be something done by the people, and if the people had bothered with becoming good, they might be able to do it, more or less.

But one can make an even worse blunder than megalomania and that is, because you are unable to do what no man can do, to decline to do what every man can do – to indulge in megalomania so as to cancel yourself. First you picture the situation before us, the complexity of the way things are, and unleash your infallible projections about what is possible – and then you decline to indulge in ‘theories’ about good government, which is ‘childish’.

To the Stoics, to the more advanced of the ancient Greeks, to medieval Christians, this is completely backwards: it is the jaded ‘realist’ who is off in fantasyland. To theorize (for Plato) meant to give witness to the spectacle of the good. You will be surprised to learn, given what we have been taught ‘theory’ is, that the English word ‘theatre’ is derived from the Greek word theoria (θεωρία), because the meaning of theoria is in fact a sight or a spectacle (for more see here > cue up at 1:05:13). (Plato’s “divine contemplations,” theion theorion, is also translated as “divine spectacle”.)

We are to begin with what is within our power: we are to witness and report what we have witnessed. This does not involve making a savvy estimate of where it makes sense to spend our energies, then dissuading others from wasting their time on what, given our prophetic powers, is ‘hopeless’. The man who pulls away from the spectacle, trading it for his notion of ‘realism’, always becomes a generator of hopelessness. Such a person has misunderstood his own business, which is to look for what commands his acknowledgement, and in that relation of submission an ordinary man’s powers of prophecy dissolve to nothing. And above all, such a person is not possessed by hopelessness: that he ‘sees no way forward’ means nothing, because of the truth that he bends his knee to. (When we come to the painting, aware of the plot it arose in, you will see this.)

But the other man turns away from ‘powerless theory’; in his intelligence, he is focused on power as effectiveness, and so goes entirely in the other direction, and, confronted there with the defects, finding nothing that will bend his knee, sours. He becomes a sour and negative element. He indulges in no ‘futile’ talk about ideal forms (judgements of the good, the beautiful, the true) and goes among the people telling them, in effect, that what is manifestly defective is what there is (it is hopeless, the ratchet turns always against the hope). That is, he tells people to accept what is bad and this is in fact a bad man, being one who has not bothered to act as a man and concern himself not with the salvation of his people but with what is true and good. The man whose eyes are turned on the things that a man must affirm never delivers a message of hopelessness, submission to the yoke of imperfection.

A MORE CONCRETE ANALOGY

I wish this were less abstract. If this is not saying anything to you consider an illustration of absolute concreteness and look at what it tells us about our misfortune. The machine we are using regularly slips a cog and smashes the blank we are machining. One man says, There is nothing we can do about it; the cog is worn. In fact this man both lies and (thereby, in that way) fails to be a man. There is not nothing we can do. We must not fold our hands but think; the thing we ought to do we certainly can do, and that is to decide what the right thing to do here is. We are fully equipped to ask, Can we can fix this?

Suppose the answer is no: a replacement gear is beyond our means – thinking further might nevertheless reveal that the waste is not unbearable (it becomes, in our situation, an acceptable cost) – or we might find that the cog is slipped every n rotations and that we can put a gap in the feed and then let the machine crunch on nothing, cutting out the damage. The machine in this example is indeed imperfect (is deformed) but is now found to be – by our powers of estimation – still a good machine: that is, good for manufacturing what we are making, which we have correctly seen to be our actual concern.

Thus it turns out that the people in this scenario do not accept a bad situation despite its imperfections. Indeed, they reveal to themselves that they are not even in a bad situation and are not in fact faced with bad fortune. They are living men doing their job, the one that they can always do, which is to ask What the work is that needs to be done and What is required to do it – looking, that is, to something that is within their power, but beginning with an understanding of the task (not hopelessness). And that is our situation relative to politics.

THE ‘CORRUPTION IN POLITICS’ IS NOT ALWAYS THE OTHER GUY’S

The man who does not use his capacity to consider the objective of government and how it might be accomplished (because this is pointless) is what the ancients called a corrupted man. The ‘corrupt person’, according to the ancient tradition of the West, is a person deprived of his good powers by his own will. He talks himself out of doing what it is his job to do and then (as a kind of contagion, ‘corrupting others’) talks others into not wasting their time on fantastic nonsense.

A man is in no way powerless to ask what job the machine of government ought to do. But the corrupt man ‘sees so far into the nature of things’ that he cannot see into himself, and the nature actually given to him, and so he is corrupt. (The meaning of ‘corrupt’ in our tradition is actually decayed, the decaying thing losing its God-given beauty; more on this here > at 17:53). Corruption is refusing one’s nature: turning from it, not exercising it. Such a person refuses to be what

man is by nature, a political animal,”

Aristotle, Politics, in The Complete Works of Aristotle,

ed. Jonathan Barnes (Princeton University, 1984), vol. 2, 1253a2

a creature who is part of a functioning society, choosing instead to be an individualist: one who tosses away the business of ‘championing what is right’ to get on with his own life. This is a process of uglification. It is the fading and withering of that particular quality – that beauty – that marked the citizen (involvement in the improvement of things for all).

THE INNER QUESTION

That is why I have said that the question I began with, concerning government, really bears within it another and greater question: who are you, what kind of person? A person in despair, who turns his or her back on fellow citizens – that is, a person who is not really a citizen? Or, in fact, a citizen, who must be (or so I am suggesting) a person acquainted with the ideal, a person who has had some pivotal and transformative experience of utterly transcendent power. (Again, this will be seen in the circumstance of our painting.) Greater than failing human power is the power that commands submission, commanding it sometimes because it has come out of the blue, when all was lost, showing that all was not lost.

[]

Perhaps the question I opened with, and the question it conceals, are odd questions to ask in an essay on art but you will see before long that what I have just noted is directly linked with the creation of the work of art we will look at. That work also bears a second significance relative to that question. It appears to have been a purpose of past art – manifest in this picture – to help the citizens of a state to do exactly what I have just explored: to decide the proper form of government, or present the way in which it was decided, display the ideal that it is entwined with, so that they could take pride in it, and do so as participants. That there is art with this function is well worth our attention.

When it is noted that

Simone Martini painted his Maestà as the ideal of the good and just government,”

“Art in Tuscany”, Traveling in Tuscany

that the painting in question is from 14th-century Italy might seem to be a drawback but in fact it is not. We who, in our advanced era, have no formulation to offer of the ‘good and just government’ find ourselves in no position of superiority to those late-medieval people. By sheer reflex we will likely think them possessed of a crude and – what is the word – medieval conception of governance (a system imperiously foisted on a hapless people, etc.), but it so happens that their system was a republic, a political system whose characteristics and virtues the pictures we will look at were created to put on display for the people of Siena – but, to be more exact, to instruct those people in, when those members of the public visited the town hall and looked around them at the pictures on the walls. When do we ever do something so full of hope? We can wave the flag, and repost Harlequin-romance-type pictures of muscled, armour-clad heroes with big jaws, but when do we ever rise to the medieval heights of teaching anyone something?

3 | The design of the state

You might be able to name the theory of government that your country has chosen; perhaps it is even a republic. What is the nature of that government; what are its virtues, and what is the source of its strength? That is what is answered by the paintings covering the walls of two rooms in the Palazzo Pubblico (meaning the ‘great building of the people’) in Siena, Tuscany. There is too much imagery to look at these all at once, so I will divide our look into two instalments. The best known of these are the three walls covered by the frescoes of Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the Palazzo Pubblico’s Sala dei Nove (or Room of the Nine), painted in 1337–40. About these paintings the political historian Quentin Skinner has indeed asked,

what exact theory of government, what ideal of social and political life, is being held up for our admiration in [the] dramatic way”

Quentin Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist

as Political Philosopher,” Proceedings of the British

Academy 72 (1986), 1

Lorenzetti employed in depicting his subject? It is in fact quite unusual to have a work of art studied by an historian of politics, but that we have such an account in Skinner’s treatment of Lorenzetti’s pictures is due to the way they answer, substantially, the question that I began with. As Skinner put it,

If we wish to see the rule of law imposed, the common good upheld, the blessings of peace attained, under what specific form of government should we ideally seek to live our lives?”

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher,” 20

Looking back from the 21st century we might presume that in late medieval Siena there was a settled answer to this question – the ‘traditional’ answer, the answer of the ‘Western tradition’ – but Skinner writes that

among scholastic writers of this period there was no agreed answer to such questions about the best form of government.”

Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher,” 20

Those aware of Aristotle’s classification, in the Politics, of the four types of lawful regime (monarchy, aristocracy, democracy, and a mixed form conceived to reap the differeing benefits of these types, in a given situation) picked one or the other. In the Italian peninsula (I presume you already know that there was no country of Italy for centuries to come) a favoured solution was the city state, which is the answer chosen by Siena, which in the 12th century became a free or self-governing commune, which is to say an ‘urban community’ that was ‘free’ of subservience to any king or emperor.

As was noted in the 13th century by Brunetto Latini, in this form of government (“which is peculiar to Italy”, he writes), the citizens elect their own magistrates, granting them power

only for a single year [to act] in whatever way seems most beneficial to the common good of the city and all their subjects”.

Brunetto Latini, Li Livres dou Tresor (c. 1260),

cited by Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist

as Political Philosopher,” 21

It should be noted that this mention of the “common good” includes morality, since today, by contrast, the very same expression is often used to mean ‘the good we really do, even now, have in common’, not morality but the other good that we are all still agreed on (jobs, health-care, crime-reduction). Skinner notes that this plan was to be exercised

in line with the civil-law axiom – beloved of all these writers – to the effect that ‘what touches all must be approved by all’.”

Skinner citing Giovanni da Viterbo’s Liber de regimine

civitatum (1240), “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as

Political Philosopher,” 21

As it happens I have just cited two of several books written in that period expressly

to instruct the governors of Italian republics on their duties and their prerogatives”

Maurizio Viroli, “In Defence of the City-State,” (10 March 2021)

– much as Machiavelli would do in The Prince three centuries later. But a notable difference is that the early Italian republics were advanced as Christian states: they were adopted as ways of fulfilling our duty to God in our social life – not as ways of achieving our particular ends as leaders (moving religion and morality off to the side, out of the ruler’s way, as an impediment to that purpose). (Machiavelli was the first ‘modern’ political theorist – that is, the first to ‘compartmentalize’ politics: to exempt it, on account of its supreme importance as our means of attaining crucial goods desired by the people, from the ‘evil’ constraints of moral fastidiousness.)

As Thomas Aquinas had explained in his own writings on politics, human beings are not given a social order (in the manner of a pride of lions); we are compelled by our nature to conceive one: to arrive at and detail the form of government that is right.

The fact that man operates, not by instinct, but by reason makes social organization indispensable,”

Dino Bigongiari, The Political Ideas of St. Thomas Aquinas

(New York: The Free Press, 1953), vii

and that power of ‘organization’ is bestowed on us. Aquinas had advocated monarchy as the best form of order but appreciated that there are circumstantial considerations and he also praised civic governments: the kind that had arisen in the part of the world he had come from.

We should look at the situation of Siena that was background to its adoption of the republican form of state, but there is a barrier to our entire discussion that we should first get into the open, so that we can go around it.

4 | A barrier

In writing the above remarks on politics as morality I could not help but recall the incredulity of Christian students (whom I taught for a decade and a half) when they were presented with that notion. The mixing of politics and morality was thought, by more than a few students, to be not just quaint but the sign of an age still laughably naïve in its conception of man. Surely the politician, in a fallen world like this one, was compelled – and if he or she had integrity, intending truly to serve the people’s welfare – not to ‘go by the book’ (or rather, the Book) … so as to do them actual good. I understand the difficulty that they were grappling with (the image of their own time full-blown in their heads), but when Christians are raised to reason along with Machiavelli as full Machiavellians, something has gone wrong.

Perhaps, those students might have thought, at one time it made sense to align politics with morality – back when ‘everyone was a Christian’ (as if there were such a time, or as if nominal Christianity were quite enough), but surely this line of thought is quite misguided.

First, it is surely full of unjustifiable assumption to think that the wild people of warring trecento Italy would have welcomed this moral sort of Christian government because of their supposed Christianity (or, ‘Christians’ will accept governments restricting immorality while people today will not). This seems to me to show very little familiarity with what immoral behaviour actually is. People who engage in immoral behaviour very often do so under a justification; they do not consider their behaviour to be wrong.

For instance, when historians of medieval Siena speak of “the problems which presented most difficulty to the commune”, and specifically of the greatest “threat to internal peace”, we might suppose that they are referring to a lawless underclass, the primitive rabble. Instead they tell us that

the threat to internal peace came most of all from the great families, principally because their wealth gave them”

Daniel Waley, Siena and the Sienese

in the Thirteenth Century

(Cambridge University Press, 1991), 97, 99

the rich person’s sense of entitlement to do as no one else dared to do. The rich, being manifestly exceptional in what they are able to do, find it quite easy to believe they are ‘exceptional in every way’. How does that person’s Christianity (which we have called ‘genuine’) equip him or her to grasp that their behaviour is immoral – in some way unjust, which is to say anti-social? That a government or a population is Christian does not ‘take care of’ this problem. This is one of the problems the right form of government will have a way to manage.

That an historian names this concern about the rich as an ingredient of Sienese politics is a testament to something in Siena’s own political tradition. The Sienese formed a government conceived to address this.

OUR HANDICAP

The point that I am trying to make is that we, thanks to our history, are uniquely underequipped to participate in discussions of politics owing to our caricatured conception of morality, which politics (as we routinely deny) is always concerned with. After more than a century of politics of a liberal stamp, we bring to the discussion the particular distortion of morality that was critically useful in remaking Western people everywhere into the products of a liberal form of society. Government is always a central manufacturing instrument. We will see what kind of people Republican people are (in the Sienese republic); liberal people are different.

(If it is unclear what I mean by liberal governments, these distance themselves from ‘morality’, which they conceive as a project-of-personal-self-direction; because we have different moralities we could not have a government ordered to morality; we must have one ordered to liberty. This sets up and indeed canonizes the view that choosing to realize inner promptings is the only neutral way to describe what human beings are really doing, and so is the correct way for governments to see their subjects. Thus, because every government governs separate individually directed beings, the actual task of government is to remove those barriers to free self-direction that are thrown up by others. – The trouble with this is that this approach demands that you abandon the entirely different, indeed rival, understanding of what people are really doing in life as not neutral – abandon it, that is, because it is not neutral: but this is a deception, because neither way is ‘neutral’. The so-called argument for liberalism exploits the perception that liberalism’s view of the operation of human life is just descriptive in nature, when it is not.

Take note that the defining feature of the so-called ‘moral’ views that liberalism replaces [Aristotle’s, or natural law approaches] is not their dos and don’ts but their conception of human life. The struggle today is not between “Virtue People” arguing for ‘the Good’ versus “Freedom People” who care about liberty, and anyone arguing that way is just engaging in misdirection [to turn you into a liberal]: getting your eyes off the real issue, which is what human life is all about.

There is no default answer to this question that we can all safely assume as a starting point, as liberalism pretends. By fooling people to believe there is, liberalism manipulates them to adopt its in no way neutral answer to the question at issue: human life is the project-of-personal-self-direction. – But enough about the liberalism that handicaps 21st-century people.)

It would never occur to liberal-minded people, to people fooled by liberalism in this way (Christians being largely captured by the rhetoric), to think that that problem posed by the rich was both a moral problem and a Biblical concern.

That it is a Biblical concern (as I believe you will see the Sienese make clear) tells us something else: this is a second way in which the view so commonly held by Christians is misguided. People today are not ‘against Biblical morality’. No doubt they are against certain parts of it, but that I am ‘against only this’ can follow the claim that I ‘accept this morality almost completely’. The contempt for Christianity that has brought about ‘Negative World’ (Aaron Renn) does not turn a person against the fragment of moral politics that I have just described. Such a person might think that Marxism provides a better solution to the rich-person problem than Christianity, but to say this is already to have joined in a weighing of merits, and Marxism has its own baggage to weigh.

The class issue that I have just brought up, as an issue in 13th-century politics, nicely returns us to the question I opened with, concerning a political system – not the way in which that ‘machine’ was used or the quality of its users, but the scheme itself. This will bring us finally to the painting we want to look at, better equipped to do so.

5 | The free city of Siena

BEFORE FREEDOM

At least a glance at Siena (who these people were, what concerned them) is required to pay attention to the government Siena gave itself, when it was free to do so.

By the 12th century German and French emperors and kings had established connections with Tuscany, making claims and forging loyalties. Siena was located on the trade route connecting northern Europe with Rome. Its closest neighbour (only 78 km or 50 miles distant) was the larger and more powerful town of Florence, economically disadvantaged by being off that route and having no direct access to a seaport (as Siena did).

Siena became free in the 12th century when the imperial government in Italy collapsed, giving rise to two positions on the hierarchy of powers. Rome (250 km or 150 miles south of Siena) was the seat of the Pope, head of the Western Church. But it was then being asked, does the authority of earthly rulers come directly from God, or from God through the authority of the Church: that is, is a king answerable to a pope? The two possible answers turned into two rival and warring factions named the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. The historian Titus Burckhardt explains that

in the opinion of the Guelphs the unity of Christendom depended on the Pope’s supremacy in all matters whether religious or secular. On the other hand the Ghibellines claimed that the Emperor, as the administrator of justice, and the Pope, as supreme priest, both held their positions immediately from God: for had not Christ Himself said, ‘My Kingdom is not of this world’, thereby setting apart his priestly successor from secular dominion?”

When we hear, with astonishment, of Renaissance popes returning from battle on horseback, as generals, our view is the upshot of a dissent rooted in this time, voiced by those who said that Jesus, speaking of ‘the things that are Caesar’s’, acknowledged

the Roman Emperors for all time to be the legitimate administrators of social order and justice. As great a man as Dante strongly defended this latter conception.”

Titus Burckhardt, Siena, City of the Virgin,

trans. Margaret McDonough Brown (Bloomington,

Indiana: World Wisdom, 2008), 4

Both sides actually agreed that

the spiritual order stood above the temporal order or that on the latter plane the Emperor was the trustee of justice,

but the entanglement of roles guaranteed conflict, and this was a conflict that a concrete government would have to resolve. For instance,

The Emperor, when appointing or dismissing priests of princely rank, could … claim that they were princes and as such were subservient to him, their secular ruler, but nonetheless in such cases he encroached upon the territory of the Church…. That the Pope held princely rank was very strongly censured by Dante who considered it to be a betrayal of the apostolic example of poverty.”

Burckhardt, Siena, City of the Virgin, 4

Rome, of course, was a Guelph city, giving allegiance to the pope.

Florence was also Guelph, and Siena lay between them. Consequently, the Holy Roman Emperors from Frederick II to Manfred perceived Siena, … traditionally Ghibelline, as an essential support of their project of restoring the rights of the Holy Roman Empire in Italy.

Jane Stevenson, Siena: the Life and Afterlife of a

Medieval City (London: Head of Zeus, 2022), ch. 4

In the 12th century, however, the Sienese looked to gain independence from the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa (head of a largely German state extending itself into Italy), and Siena engaged in a series of battles between newly formed leagues of north Italian cities and the German forces. It succeeded in 1183 and in the Peace of Constance was granted what one historian describes as “communal autonomy”.

A FREE CITY

And here we encounter an attitude strangely reminiscent of the current moment. Free cities were free to rule themselves; they were under no king or emperor. Thus, though they might be emphatically Christian, they could also be counted outside Christendom, since not subject to whomever others recognized as its political head. (Christendom was not an abstraction; the ‘dominion’ in that word was an actual political government.) This put the free town under a certain kind of scrutiny. As Burckhardt puts it,

each free city, … being alone, … was all to itself. If it happened … to be in the wrong [over some issue of contract or accepted custom] this sufficed for [the town] to be treated as an enemy and as a danger to Christian society, and his territory could be burned and plundered with a good conscience.

Burckhardt, Siena, City of the Virgin, 4

Though two sets of people may both be Americans, if one group should violate a taboo of the other, by which that other group defines America (‘fundamental American values’), that former brother can easily become ‘an enemy and a danger to America itself’. If the self-governing city state of Siena took a different path from its neighbour state (the key neighbour being Florence), the Sienese could be treated as a threat to the Christian order, in that they had in a certain manner, by their independence, stepped out of it, and their territory could be burned and plundered. (As Burckhardt notes, the charge of evil might be a handy pretext for seizing what that ‘enemy’ controlled. Property, yes, but it could just as well be power.)

Though two sets of people may both be Americans, if one group should violate a taboo of the other, by which that other group defines America (‘fundamental American values’), that former brother can easily become ‘an enemy and a danger to America itself’. If the self-governing city state of Siena took a different path from its neighbour state (the key neighbour being Florence), the Sienese could be treated as a threat to the Christian order, in that they had in a certain manner, by their independence, stepped out of it, and their territory could be burned and plundered. (As Burckhardt notes, the charge of evil might be a handy pretext for seizing what that ‘enemy’ controlled. Property, yes, but it could just as well be power.)

In the following lines from Siena’s charter of freedom, issued by the emperor’s son, note the mention of the contado (the lands around the city of Siena) as containing men “belonging to” the bishop.

“In the name of the Holy and Indivisible Trinity, We, Henry VI, by divine favour, king of the Romans … make known to all the faithful of the empire, present as well as future, that in view of the merits of our trusty subjects, the citizens of Siena, we grant them all the free election of their consuls. … We grant them full jurisdiction in the city of Siena, and outside the city, in the contado, over the men belonging to the bishop of Siena or to any Sienese resident at the time this document is drawn up,….

Cited in Stevenson, ch. 3

This is the seigneurial system of feudalism, in which a lord is responsible for the peasants on his land. The “citizens” mentioned in the charter belong to a city and have particular civic rights and obligations. The landowners, being residents in the city, fed the city with the yield of their crops (this was, of course, business), and there is a connection between these landowners and a particular cause of Siena’s success. Siena was a banking centre (the link with farming still marks financial language).

Financiers or bankers had been prominent in Siena since the beginning of the thirteenth century…. Some of the families were very wealthy indeed and the greatest of them were the owners of widespread lands…. Wealth from land no doubt provided the initial capital [or ‘seed money’] for the bankers, and success in finance was followed by the acquisition of more land. Siena’s bankers were not merely specialists in finance, but were landowners who had learned the elementary analogies of breeding from money as well as from stock, and of ‘ploughing in’ financial profits as they ploughed the land for the seed which was to provide the grain harvest…. The Sienese were closely connected with rise of the papacy as an ‘international’ fiscal power … [and] the spirit of financial enterprise – which needed no inculcation by Calvin, whatever some historians and sociologists have implied – breathes in the letters of the Sienese bankers.”

Daniel Waley, Siena and the Sienese in the Thirteenth

Century (Cambridge University Press, 1991), 26, 27

In the 13th century, however, owing also to financial rivalry, these neighbouring towns went to war; a letter of 1260 contains the line,

Be it known that in Siena eight hundred horsemen have been assembled to bring death and destruction to Florence.”

Burckhardt, Siena, City of the Virgin, 6

HOW DO THESE PEOPLE THINK?

Before we turn to the actual government one event in connection with that battle is worth examining as it tells us something about the way the Sienese thought of the government they had formed when they had won their ‘autonomy’, and that is that they were not autonomous.

On the eve of this battle in September of 1260 Siena was surrounded by the superior forces of Florence. On that evening, the tumult within the city impressed the members of the government (the city council) as a situation in which something must be done – we are looking here at an act of governance. The council members reached the conclusion that a leader must be chosen – a leader, that is, of the people in the performance of an act, such as a single person of good judgement could and would perform. Looking for someone who had influence in both the town and the countryside,

their choice fell unanimously on Buonaguida Lucari, a Sienese layman of noble birth and a man of irreproachable religious reputation.”

From the steps of a church this Buonaguida called out to the crowd and turned their attention away from the human help they had been promised by a force from the German imperial army. According to the record made of this event he said:

‘Citizens of Siena, it is known to all that the fate of our city is entrusted to our liege-lord King Manfred. But at such a time as this it would seem to me to be right to lay ourselves, our possessions, and the whole city of Siena at the feet of the Queen and Empress of Everlasting Life, the glorious and Ever-virgin Mother of God. And the better to present our gift I beg you all, for the love you bear Our Lady, to accompany me in what I shall do.’ Hardly had he finished speaking when he divested himself of his outer garments … removing his shoes and cap. Barefoot and with bared head he now received the keys of the city, and preceding the crowd he carried them to the Cathedral,”

where a Psalm was being sung, at the end of which the bishop received Buonaguida. After prayers and prostrations and a procession around the cathedral Buonaguida approached the principal altar, behind which was an “image of the Virgin Mary” (but take note that altarpiece images of Mary are always depictions including Christ). Buonaguida then addressed the Virgin, in the following words:

‘Holy Virgin, glorious Queen of Heaven, Mother of sinners, of orphans and the widowed, Protectress of the poor and lonely, I, the most miserable of sinners, present into Thy protecting hands this city of Siena and all her lands, in token of which I herewith lay these keys to the doors of our city upon the altar.’ Having laid the keys with great reverence upon the altar he begged a notary, who was present, to write a document to witness this solemn pact and the presentation of the keys. With great fervency Buonaguida then continued: ‘O Mother, Heavenly Queen, I beseech Thee to accept this our gift even though it seems small compared with Thy riches. Madonna, Mother of God, I beg Thee to receive our gift with just such love as that with which I, miserable sinner though I be, lay it before Thee. Furthermore I pray that Thou wilt extend Thy gracious protection to the inhabitants of this city and to its lands that they may be spared from the hands of the unjust and evil Florentine dogs and from all who dare to occupy, oppress, and devastate this town’”

Burckhardt, Siena, City of the Virgin, 9, 10–11

– or, as another translation puts it,

from the hands of the arrant curs of Florence, and from all those who would occupy, oppress, and destroy her.”

Cited in Stevenson, ch. 4

The political act, recorded as such by a notary, was to officially give the city of Siena to the Mother of God. (I hope you do not mind if, just to speed our movement to the painting we are still on our way to, I do not pause to address the question, Why Mary, why not Christ – except to say one thing: the crown promised by Christ is a crown promised to flesh-and-blood human beings. I will look at this crown and take up this question about Mary in connection with another painting.)

You might imagine that that political act must thereby be concluded, but it was still incomplete. “What touches all must be approved by all”: what was thus far done by one man’s word must be done by all, if what he was the voice of, an act of the city, were to be done. Buonaguida and the bishop, priests, and citizenry then picked up

the painting before which the donation ritual had been performed[, exited the church] in procession, [bearing] the sacred relics of the cathedral, … and they wound their way through the narrow streets of the entire city.”

Stevenson, ch. 4

That is, the image of the Virgin borne in procession was her symbolic presence among the people (on the reality of symbols, see here). The participation of the people, walking with her (and the town’s patron saints) through their streets, was the people’s participation in the act of giving their city to God, subordinating themselves to the rule of heaven. The following day the Sienese met the Florentines at Montaperti and crushed their enemy. The terms of submission after the victory made reference back to the political act I have just related, describing the Virgin as “defensatrix and gubernatrix” (defender and governor) of Siena.

Stevenson, ch. 4

6 | Republican government

We must look now at the painting, but it would be better to do so after gaining a summary conception of what the government of Siena was. Officially it was called the Respublica Senensis, which names its type: a republic. Sometimes Siena’s government is called an oligarchy, but note that

the question to be asked concerning a city-republic is not ‘was it controlled by an oligarchy?’ but ‘what sort of oligarchy or oligarchies controlled it?’

Daniel Waley, Siena and the Sienese in the Thirteenth

Century (Cambridge University Press, 1991), 74

Republics are oligarchies not democracies; they all rely on the judgement of, as James Madison would later put it,

a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interests of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice will be least likely to sacrifice it….”

James Madison, “Federalist No. 10,” in American State

Papers, The Federalist, and On Liberty

(Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1952), 52

The government of Siena was also called the Comune, literally meaning the “community of the city” but also that community as represented by those in government.

Waley, 10

More exactly, the term says that its government is ‘common’ to the people, as per the Roman conception of the republic.

A res publica is the concern of a people, but a people is not any group of men assembled in any way, but an assembled multitude associated with one another through agreement on right….”

Cicero, De Republica, book V

That is, to form a republic you do not just call a bunch of people together to make a government, you find a group that is already agreed on some conception of what is right – indeed, on the best conception. Republics can therefore be ordered to very different ends, and we have already seen that in Siena the conception of right meant a submission to the rule of heaven. We have also seen that that very submission involved, as historian Jane Stevenson puts it, a commitment

to keeping the nobility out of power,”

Stevenson, ch. 6

for the sake of all the people, the whole city.

In its structure the Respublica or the Comune had, on the model of a republic:

- a figurehead (a monarch-like leader like the ancient Roman consul),

- an upper body (like the aristocratic body of the ancient Roman Senate),

- and an assembly (the democratic element),

all functions generally not open to officials of the Church (which, as per Ghibelline thought, had its own work to do).

To fill this out just a little, the titular head or senior official (according to the statute that defined this government) was the Podestà (from the Latin potestas or power), whose power was sharply curbed as this position could be held for only six months at a time. To be chosen as Podestà a man must be at least thirty and knighted, or eligible for knighthood, and to be knighted one had to be a member of the upper class.

There could be no mistaking the superior social standing of one who had ‘received the belt of knighthood’.

Knighting however was not an award for valour or distinction but, simply, the mark of initiation into manhood for a member of this class. As a knight was a warrior on horseback, wealth (as in ancient Greece) was the means of securing the requirements: a warhorse, armour, weapons, a squire, and training. It was the Commune that authorized the conferring of knighthood.

Waley, 42, 47, 74, 83

The rich were by and large excluded from the main governing body, which at the time of the building of the Palazzo Pubblico was called The Nine. The task of the Nine, set out in the statute, was to bring the city to “true and right and loyal peace and unity, communally and individually (singularmente)”, to keep the people “in unity and in a good pacific and reposed (riposato, not restless) state”, and to stand for “reason and equality and justice”. The men responsible for this were to be drawn from the middle class: the merchant class that sold what the wealthy and their lands produced, a class called even then the meza gente or middle people. This was not a large stratum of the society and continuity was provided by the resulting necessity of serving among the Nine many times. Service to the lower class was secured in that each Thursday the Nine heard petitions in a session to be held “in a public and open place”. Access was part of the plan, part of the work of the government machine that the Sienese designed.

Waley, 47, 48, 93, 94

Both the Podestà and the Nine generally operated in conjunction with a General Council (the Consiglio della Campana), composed of 300 citizens (serving for one year), 100 from each of the terzi, the three physical divisions of the city. These councillors had to be the “best, most useful, and most discreet”, in sum the wisest that could be found. To become a Councillor a person must be at least twenty-five and a tax-paying citizen resident in the city for at least ten years.

Office-holders could not be councillors, nor could two brothers at the same time; heretics and suspected heretics were naturally banned.”

Waley, 49, 74

7 | Political Christian art

What at least one scholar refers to as “the glorious era of the Nine” was at the same time an era of economic decline; Florence was rising, the bankers of that city beating out those of Siena. Nevertheless, writes Stevenson,

to contemporaries, things looked very different. It was the government of the Nine which made Siena what it is today. They sculpted the civic landscape,

and were responsible for building the Palazzo Pubblico del Comune that dominates Siena today.

Given the tensions between the nobility and the civic government, and the commune’s desire to emphasize a separation of powers between church and state, it began to seem less and less appropriate for the governing body to meet either in a church or in a rented noble palace – perhaps especially that of the Tolomei, who had proved to be unruly subjects on more than one occasion.

Stevenson, ch. 6

The site chosen for this new city hall (begun 1298, completed 1310) was located at the point where the three terzi converged.

Soon thereafter the governors commissioned the Sienese artist Simone Martini to paint, on the wall of the government’s main meeting room, a suitable image. Simone completed this work by 1315: a large fresco of what is usually called, even by English-speaking scholars, the Maestà, a term referring to majesty, which conveniently absolves the non-Italian of the difficulty of translating this – but who here is in majesty?

MAJESTY

‘Christ in Majesty’ is a standard subject of medieval art, but is that what is meant? ‘Majesty’ relates to splendour, greatness, power, and authority, all four qualities of a magus or king.

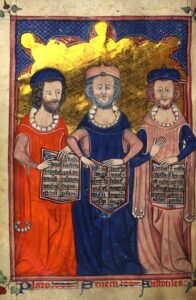

There is indeed a throne here, but whose throne? Mary is seated on it but is it Mary’s throne? Traditionally, Mary was represented in the West as the throne of Christ, a subject called the Sedes sapientiae or ‘Seat of Wisdom’ (Wisdom being understood as Christ). Is the seat of wisdom the throne of Christ?

I suspect the best way to resolve all this is to answer Yes, yes, and yes, the puzzle of such an answer resolved by the meaning of this dual image – a duality that is central to Christian thought and thus medieval art: this is an image of the infant Jesus and his mother. As a Christian image it presents created man brought to fulfilment; it is an image of God and man united, indeed of one body. We are shown Christ who as a man was within the body of Mary; and Mary who, responsive to a divine invitation (relayed by a messenger from heaven) is in the body of Christ.

So we, though many, are one body in Christ, and individually members one of another.”

Romans 12:4 ESV

Enthroned here are God and man united. A throne supports a body and the body we see here is the body of the Church, understood Scripturally. The Church should not in any way be confused with the clergy. The clergy have for most of history been a privileged class, which is to say a class with special power; the above-noted mention of Siena’s “separation of powers between church and state” is not to be read as a separation of religion and state; it was a freeing of the state from power, power of a particular sort, so that it might be replaced by divine power.

Mary had no power whatsoever and it is she who is seated on the throne, holding Christ before her. Thus the body on the throne is Christ, united with his own body: mortal people who ‘become him’ in body (it is hard to know how else to put it). (People revelling in a non-Christlike power would not, in that way, be Christlike.) The name of this enthroned Church, then, is Christ (it is not Christianity or Christians). The Church is the body of the Christ who came to earth, through Mary, to draw people into himself as part of himself, as individual members of his body (on the analogy of organs and limbs).

Now you are the body of Christ and individually members of it.”

1 Corinthians 12:27 ESV

Notably it is Mary (whom Buonaguida had called “the Queen and Empress of Everlasting Life”) who is crowned here, a crown being something bestowed: put on a person, added to them. (Even one who is born a king, who is a king by right, only becomes king when he is crowned.) Christ is a different manner of king: he is king crownless, who does not come into his majesty but is king in his very being. And, further, it is not just that his splendour, greatness, power, and authority are native to him; he is the logos of splendour (he is the splendour that shares itself with everything created, by him, to radiate splendour.) Christ is not just King but The King.

So we are not shown Mary reigning in heaven or “the Virgin in Majesty”, as one art historian who does translate Maestà put it. Mary reigns in heaven in Christ, in the body of The King (though reign she does, in this body, as the realization and manifestation of Christ’s promise).

Scholars have pointed out the resemblance of Martini’s Virgin and Child to Byzantine icons of the Hodegitria type, from

[the] Greek term meaning ‘She who shows the way’. In antiquity this meant a guide, but in Christian usage it alludes to the role of the Virgin as parallel to that of John the Forerunner [John the Baptist], showing to humankind the “Way, the Truth, and the Life” by witnessing to Jesus.”

John A. McGuckin, s.v. “Hodegitria”, in The Concise

Encyclopedia of Orthodox Christianity (Oxford:

Wiley Blackwell, 2014), 247

![]() In Byzantine icons Mary signals this by pointing to Christ, literally. In Martini’s image we do not see pointing, yet she does the same thing in another way, “showing” Jesus to humankind by holding him up before us, but also holding him out to us, presenting him to us (notice how he stands on her hand, as an offering). She gave us and gives us a visible Christ.

In Byzantine icons Mary signals this by pointing to Christ, literally. In Martini’s image we do not see pointing, yet she does the same thing in another way, “showing” Jesus to humankind by holding him up before us, but also holding him out to us, presenting him to us (notice how he stands on her hand, as an offering). She gave us and gives us a visible Christ.

MOTHER & CHILD

Here too we also have that image reproduced in Christian art again and again, for over a millennium, but so rarely reflected on: Jesus, “son of man”, portrayed as a child. – Why?

He is depicted here in infancy, as the child of a human mother, in the definitive state of human weakness – that weakness thematically fastened on by the Apostle Paul:

We are weak, but you are strong.”

1 Corinthians 4:10 ESV

But this is not a mere Pauline theme; it was the very message of Jesus – the very one that had been modelled by Mary, in such a way as to give Jesus earthly life, the message that John Howard Yoder expressed as

the loving willingness of our subordination, … the voluntary subjection of the church….”

John Howard Yoder, The Politics of Jesus:

Vicit Agnus Noster, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, Mich.:

Eerdmans, 1994), 185

Woman and child are subordinates. They are not independent (what is a child without a mother?) but dependent, upon the father who is missing from this image (the father unportrayable because divine). The loving willingness of our subordination marks the way to our destiny.

Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.”

Matthew 5:5 ESV

The thing we are not to miss – and that the government of Siena did not miss, in choosing this image as the one to preside in the room where it met to discuss the future of its city – is that the power of God is emblematized for us as weakness (the way to obtain power:

‘Power’ points in all its modulations to some kind of capacity to make things happen).”

Yoder, The Politics of Jesus, 138

Is this is not a paradox? This image, which takes up the whole of one wall, was nevertheless the lesson. It was even a warning to the earthly power of Siena, a government that indeed wielded the literal sword of justice – that the power of God is given to man in a posture of humility, weakness, reception. And this indeed is what the image shows, in its presentation of roles.

The promised power or capacity is not a power of possession but a power of reception. It is the power that flows into a being who says ‘Let it be unto me’, a being who is both in relation (in the Virgin and child image we have the image of a relationship) and taking their proper place (subordinate to what is supreme).

COUNTER-REGAL MAJESTY

How does a king speak?

I Darius make a decree; let it be done with all diligence.”

Ezra 6:12 ESV

I, Artaxerxes the king, make a decree…: Whatever Ezra the priest … requires of you, let it be done with all diligence,….”

Ezra 7:21 ESV

Mary receives the throne by altering the “decree”.

And Mary said, “Behold, I am the servant of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word.”

Luke 1:38 ESV

Recall especially Jesus’s own references to childhood:

Truly, I say to you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child shall not enter it.”

Mark 10:15 ESV

The kings in this ‘throne room’ of the Palazzo Pubblico are keeping before their eyes the promise of Christ to the man on earth who is required to rule. (A Christian may rule. It is not Christ who calls the Christian to shy away from every seat of power, given that that seat is ‘occupied by Satan’, prince of this world.)

The promise of Christ to the city ruler – perhaps I should take this opportunity to note that the concept of ‘civilization’ is derived from the Latin ‘civitas’, or city – is that the power of God, to do what is worthy of God, is given to one who receives, one who submits – one who knows that he himself is effectively headless and lacks the wisdom to govern, and so must become the instrument of the Head, the limb moved by the will of the enthroned body – and, further, that in this submission lies his salvation.

Christ is the head of the church, his body, and is himself its Saviour.”

Ephesians 5:23 ESV

But I want you to understand that the head of every man is Christ, the head of a wife is her husband, and the head of Christ is God.”

1 Corinthians 11:3 ESV

Not that this confirms it to be true, but this is also the ancient insight of the Greeks: it is a confession of ignorance that is the beginning of wisdom.

THE WISDOM OF SIENA

Indeed, this is the wisdom of Siena, the wisdom it publicly recognizes here by way of this image. In the painting the ‘infant Christ’ stands in the lap of his mother as the central figure, holding up one hand in blessing, while in the other he holds a scroll of parchment bearing words from the Apocrypha, the very opening line of the Book of Wisdom:

Diligite iustitiam qui iudicatis terram | Love justice you who are rulers on earth.”

Love – this term so foreign to politics as we think of it – has already been referenced in this discussion: “for the love you bear Our Lady,” said the man handed the keys of Siena, asking that the city give itself to the Virgin; the one line quoted from James Madison contained words, “love of justice”, that echo the Book of Wisdom.

This is not a ‘church’ picture (to shift back to our usual language) but a political picture made for a house of government – but even so it is a Church picture in the sense that I have been presenting: not in that it is a picture for a Christian society (again, we never truly have such a society) but in that it is a picture given to a ruling class (one drawn from the society as a whole, so presumably acceptable to the whole society) bearing the wisdom of the Church, the wisdom received by those who truly are members of the body. And so we see in the retinue of Christ and his mother a company of saints and angels.

The picture is an offering of the wisdom of the Church: holds out to the leaders of the city the promise of justice, if they participate in the order in the way of the Virgin Mary, in the way of Jesus, who

accepted his own status of submission.”

Yoder, The Politics of Jesus, 145

Note that the words on the scroll are an injunction: the rulers of Siena are not ‘handed the law’ as much as called to love what is central to the law, which is justice. (All of the Ten Commandments, recall, are commandments of justice: of what is owed or due to God and to man.) As a New Testament image, however, the heart of the law is set out not for obedience (as the Old Testament had been understood, or perhaps misunderstood, to do). What Christ’s left hand holds out to the viewer (the Council member, the visitor to the Palazzo Pubblico) is a call to love the law, not obey it – to love justice, the orderliness at the heart of the law – and to do so while coming before a child and a woman, in all their gentleness and beauty. The art historian Stephen Zucker calls attention to this:

There’s also a degree of elegance that is consistent with 14th-century Sienese painting. The figures are elongated, their hands are impossibly long,….”

Steven Zucker, “Simone Martini, Maestà,” Smarthistory (3 December 2021)

The ‘figures in 14th-century Sienese painting’ that Zucker refers to are all saints and angels; what these artists all laboured to present is the perfection of these saints and heavenly spirits. So, in Martini’s political fresco we are far from the world of pragmatic and necessarily harsh effectiveness that Machiavelli haunts. We are in the court of Siena which, in the room of this painting, is below but oriented to the court of heaven. The governors of Siena ruling from this room have come before Christ, a figure offering them a divine power that would serve them even on earth, a power that they had experienced fifty years earlier after giving their city – in helplessness, in submission – to the Virgin.

The ‘figures in 14th-century Sienese painting’ that Zucker refers to are all saints and angels; what these artists all laboured to present is the perfection of these saints and heavenly spirits. So, in Martini’s political fresco we are far from the world of pragmatic and necessarily harsh effectiveness that Machiavelli haunts. We are in the court of Siena which, in the room of this painting, is below but oriented to the court of heaven. The governors of Siena ruling from this room have come before Christ, a figure offering them a divine power that would serve them even on earth, a power that they had experienced fifty years earlier after giving their city – in helplessness, in submission – to the Virgin.

The image continues to do this. – To those students who thought that We have no power to deliver the good as a Christian would see it, or, In a world like this nobody wants the good of any ‘book of wisdom’, or, The day is long past when we could count on people to respond to any capital-J Justice of Christianity’s sort: to such people the Christ in this painting presents himself, as he did to the downtrodden and conflict-riven of Siena. The infant Jesus, a weak individual who is the emphatically powerless foundation of what would become, after Jesus’ death, an entire way of life, offers himself as one with a link to heaven – to be correct, with a father in heaven. (He said,

Pray then like this: ‘Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name’.”

That is, a defender and governor. This child who at twelve would ask his mother, do you not know

that I must be about my Father’s business?”

Luke 2:49 KJV

would harness power of an unearthly nature by submission to that business, not by seeking the power that was available to human beings with their face turned, ‘sensibly’, to the actual forces of the world. In commissioning for their state house an image of the divine majesty that draws human beings into heaven, were they giving up on politics, as a lost cause, to think instead of their souls, since that was all God cares about?

The saints depicted to the left and right of the Virgin and Child, which include the four patron Saints of Siena: St. Ansanus (an effective evangelist during the Diocletian persecution), St. Savinus (a Bishop martyr), St. Crescentius (a child martyr), all three killed in the same persecution, and St. Victor (martyred under Marcus Aurelius). The power of these saints – the power to give their lives, to do justice and give to God what is his, giving pagan Rome’s phony gods also just what they were due – is a love of justice via a love of God. A love of what is real, a “capacity to make things happen” that is real.

A PATHWAY TO POWER (&, WHAT IS A BLESSING?)

That we are talking today about Jesus, through a painting of him, is surely due not to his human power but to the divine power he marshalled in his human life, turned as he was, as a subordinate (a child, a carpenter, a preacher) to receive something.

Here, with his right hand, this converter of unbelievers (of those who hated him to the point even of killing him) bestows the power that human beings so commonly deprive themselves of, by how they live: for that is what a blessing in his tradition is.

Blessing is bestowing – indeed via the ‘good words’ (eulogeō) that are said, but a blessing is not just words said (when we speak of the ‘blessings we have received’’ we are not talking about words said). Christ’s act of blessing is the granting of something.

It is like ‘anointing’. When anointed as a king (with spoken rites, a ritual use of oil), Saul and David became kings, that is, assumed the powers of the king to judge and govern, came for the first time to command those powers. Blessing too is this kind of ‘switching-on’ of the capacity at issue, but unlike anointing this bestowal is not completed. It is an act of relation in which something is begun (like responsory singing, in which a verse is begun by the cantor and completed by the choir).

The blessing is – just as it is depicted, in fact, in Martini’s picture – a bestowing of something by a call into something else. The bestowed power to rule in the right way is a function of loving justice (Diligite iustitiam), which is a “participation in the realities of the divine world”. That is the heavenly world that Martini undertook to represent, of a woman and a child, … a company of the beautiful, the saints (thirty are shown sharing the space of Christ and Mary in heaven).

Love justice you who are rulers on earth”

Wisdom of Solomon, 1:1

This still leaves, for us, the question of the nature of that rule – of what a government so directed would look like, or rather, what its acts would be. That was also a concern of the councillors commissioning art for this new seat of power: and that is exactly what we are shown in the adjoining room and its frescoes, generally known as the ‘allegory of good government’, to be looked at next.

Artist

Simone Martini (c. 1284–1344)

Date

1315

Hall of the City Council in the Palazzo Pubblico Comunale, Siena

Medium

Fresco

Photo credit

Steven Zucker, Smarthistory